There’s a common myth that the black community speaks of gun violence only when law enforcement is its perpetrator. That marches, protests, and ad hoc assemblies ignite only after deaths like Stephon Clark’s, killed by a Sacramento police officer last week in his mother’s backyard. Zealous cable-news pundits continue to publicly hawk the stale notion that mum’s the word when it comes to the violence they brand as “black-on-black crime,” as was the case when Shamar Curry was killed last year in a drive-by shooting at Rainier Playfield.

But no: We cry, we agonize, we rage, we deliberate, we demand justice. We’re too often overlooked. That’s what I experienced at Curry’s vigil last July.

I was reminded of this while watching last weekend’s March for Our Lives demonstrations held across the country. As a multiracial and generational procession of students, teachers, parents, and gun-restriction advocates filled my television, I lauded their attempts to claim a corner of reason in the mad battlefield that is our country’s gun debate.

However, I couldn’t help but think of those victims of gun violence whose plights remain invisible. Whose deaths remain tolerated.

Last year there were 30 homicides in the city of Seattle. Of those, 19 victims were either black or Native. Combined, both races barely crack 9 percent of the city’s population, yet they accounted for 63 percent of homicides in 2017.

Our city and county officials meet these deaths with a relative silence, one that became more conspicuous after my friend Latrell Williams was killed last year on his way to a corner store. While his death remains unsolved, babblers in my neighborhood who will never go on the record to media or police—feeling an inherent and historic mistrust of both when it comes to distilling either truth or justice— say it was a case of wrong place, wrong time: a young gang member going through an initiation, needing to prove himself by killing someone, anyone. Latrell happened to be that unlucky someone.

He left behind a son, a mother, kids he mentored, and friends. As one of them, one who also counts himself a member of the media, I remember waiting for any statement from our city or county officials—whose communication teams have no problem rushing out responses to the misdeeds of our current President, the retirement of a valued sewer-maintenance worker, or effusive adoration for our football team.

But nothing came. In a crowded race of 20 mayoral candidates, only Nikkita Oliver mentioned him, briefly during a debate.

The radio silence wasn’t just for Latrell, but for seemingly every black homicide not involving a police officer. A source formerly within the King County Executive office said that the attitude was “We’ll mention it … next time.” When next time inevitably came, it was déjà vu.

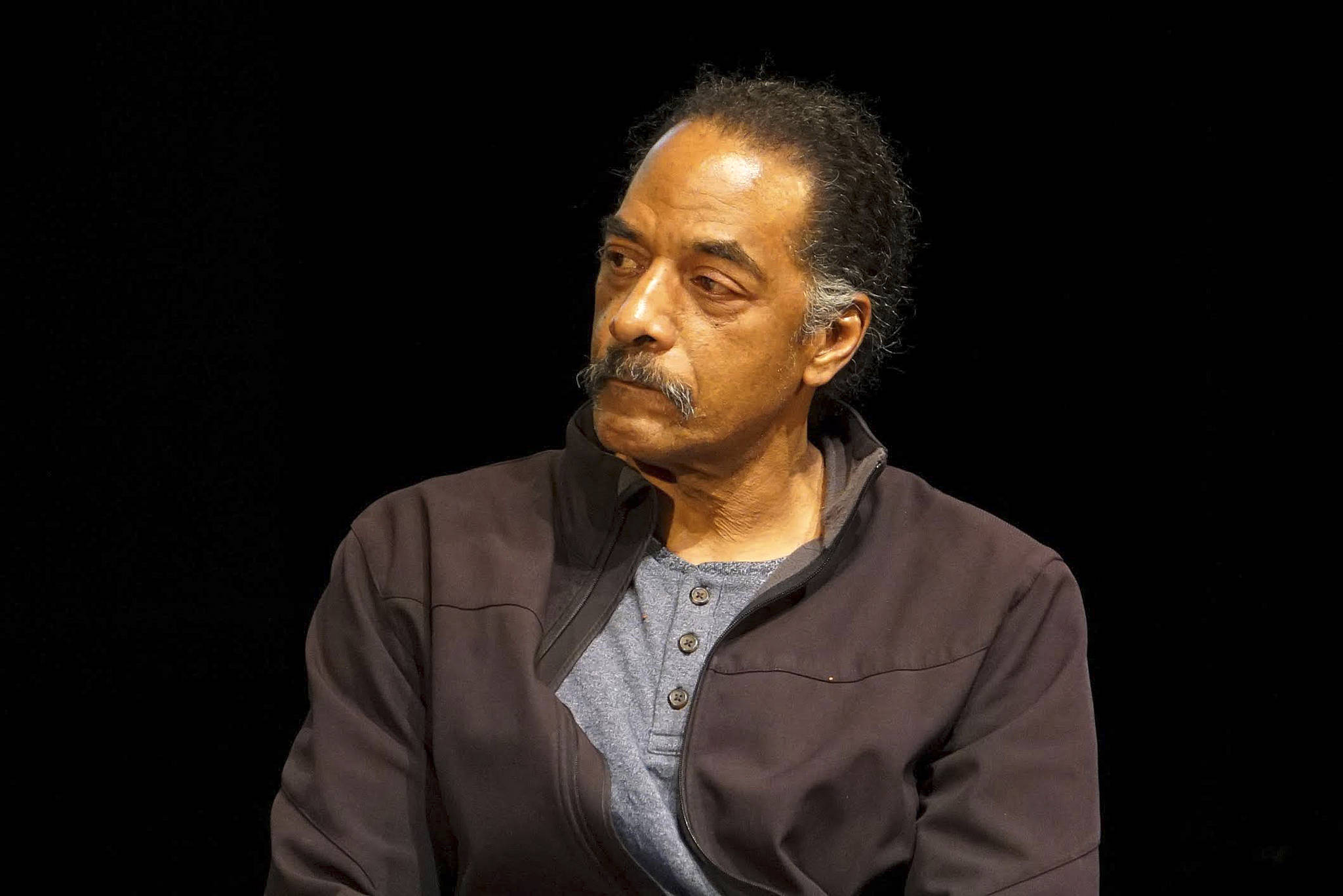

“When you have a population that comprises less than 8 percent of your electorate, the political calculus is to not make waves or rock the boat by saying anything,” says Gregory Davis, managing strategist of the Rainier Beach Action Coalition, a community-improvement organization working a breath away from where Latrell was killed. Davis agrees that speaking out about such violence might unearth its origins—causes most local officials craftily acknowledge, but are reluctant to stare down: income inequality, wealth discrepancies, and widening opportunity gaps within our public school system. If local officials actually addressed these problems, they might be able to claim more responsibility in reducing senseless deaths than national politicians.

A few months ago, I met Latrell’s mother Lynda for coffee. I listened as she reminisced about her son. She spoke about the man he was becoming. How Latrell’s 13-year-old son still swears he sees his dad on the couch watching the Seahawks at times. And how her whole heart still hurts.

Throughout, she kept saying his name. No one else seems willing to mention it.

Marcus Harrison Green is the editor of the South Seattle Emerald. His column appears the last week of every month.