Whether the weapons used are ideas or artillery, revolutions will always be soul-cripplingly brutal. Complexity and commotion are their base ingredients—neither of which is surprising considering revolutions are a result of a faction with an idea of “what society ought to be” furiously raging against the established “what society is.”

Unfortunately, “what society ought to be” will, with few exceptions, always find itself a double-digit underdog. “What society is” will automatically portray itself as the undisputed champion—its advantages too many to simply relinquish—dismissing the challenger to the title’s merits offhand before waging its own vicious counter-assault.

Historically, the clash between the two produces transformed institutions, broken spirits, awakened minds, and most of all flawed human specimens who have experienced triumphs, suffered defeats, and learned from mistakes, and at the end of it all are willing to hand the sword to others to wield in the battles to come. With the 50th Anniversary of Seattle’s Black Panther Party being celebrated this week, I was reminded that the true revolutions are never-ending.

Ask most current Seattle activists about the Black Panthers, and words about its impact will flow like glowing soliloquies. “They provide the blueprint to someone like me—who grew up in Seattle’s Central District—[on] how to fight and organize for black liberation,” says community organizer Amir Islam, who modeled the now-defunct United Hood Movement after the Black Panthers.

Others saw them as aspirational. “I look at them … [as] warriors who coveted self-education, love of art, and self-defense,” says Afam Ayika, a community organizer in the Seattle area.

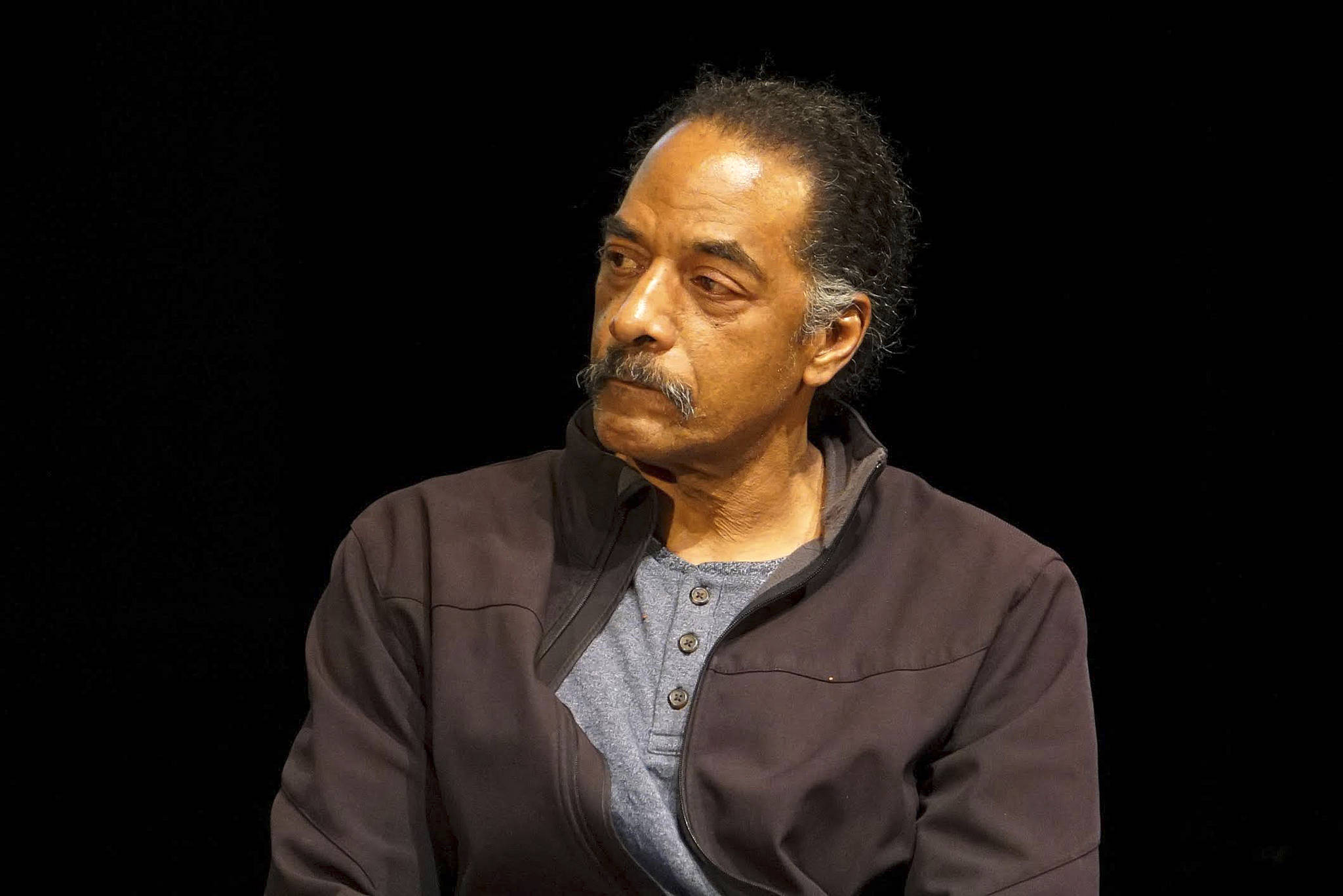

Nearly four years ago, I got to see one of them as a mortal. I spent the better part of a Friday night taxiing Seattle Black Panther co-founder Aaron Dixon around half the city as part of a piece I was working on about his group’s enduring legacy. What was supposed to be an hourlong interview turned into a marathon errand run from the South End to the Central District and back.

At the time, I unfortunately lacked all but the most superficial history of Seattle’s local BP chapter. I knew they helped start breakfast programs, were cast as more militant than both Dr. King and Malcolm X’s branches of the civil rights movement, and—depending on whom you asked in the black community—were either the greatest thing to ever happen to the movement or, though well-intentioned, arrested its progress.

When you grow up in a Cosby Show-loving household (not anymore, obviously) and you’re a progeny of Catholic private schools, revolutionary Black Vanguard politics are touched on only slightly more than any sex education not involving steadfast abstinence. But at the end of chauffeuring Dixon around in my gray Malibu that was thirsty for an oil change, we deposited ourselves at Union Bar in Hillman City. All the pro-labor, lefty paraphernalia that adorned the walls seemed appropriate for the occasion.

I’d boned up on Dixon’s legend the night before. This was the man who in 1968, at age 19, co-founded (along with his brother Elmer, Curtis Harris, and others) the first Black Panther Chapter in the country outside California. That same year, even with an unapologetic message of black determination, he galvanized hundreds of mostly white people to take to the streets to rally against his arrest on grand larceny charges for possessing an allegedly stolen typewriter.

By 22, Dixon had marched with Dr. King, was the target of constant harassment by the FBI and local police for his leadership role with the Panthers, and successfully pushed the University of Washington to add a Black History curriculum. He once entered Rainier Beach High School with an unloaded pistol to protest the economic disparities at schools in communities of color, and was accused by then-Seattle Mayor James “Dorm” Braman of being the “1 to 2 percent of the Black population causing all the city’s racial problems.”

He helped found free breakfast centers in the Central District and South End for poor black youth who otherwise would’ve gone hungry, and stridently demanded charges for law-enforcement officers suspected of assault when the phrase “police harassment” still bore dismissive quotation marks in the city’s newspapers.

Seattle’s Black Panther Chapter officially lasted only about 10 years, folding its tent in 1978, but Dixon, like many Panthers, never stopped. To this day he tours the college speaking circuit. And in 2006, he ran for senate against Maria Cantwell.

On that night in Union Bar, though, he was the legend made flesh. Tired, weary, and with all his 65 years etched on his face, he seemed completely drained. A lifetime of fighting for black liberation will do that to you.

However, he still managed to speak with me for two hours—the spirit enduring even as the body was fading for the night.

He saw a fine heir to the Black Panther’s legacy in the then-embryonic Black Lives Matter movement. He praised younger organizers for possessing a more inclusive lens across gender and orientation than his generation possessed. He found joy in the ability to pass on and equip the next generation with the revolution tools to vanquish oppression: community building, self-affirmation, acknowledgement of power dynamics, understanding of the marginalized class’s unified power, and realization of our collective destiny.

But I wanted to know why he went on. Why he continued to so fervently share his message of anti-capitalism, community reliance, and black self-determination. Police killings of black people, racist outcomes in our educational system, black wealth still a crumb of white wealth … the same battles he waged continue to find fertile fields. So why not emulate the path of so many onetime revolutionaries who opt for a more lucrative life of burnishing the “progressive credentials” of establishment institutions like the Democratic Party with their mere presence (see: Lewis, John)?

He looked at me and talked about the need to continuously reiterate that “another world is possible.” In heartache, as equally as in joy, “another world is possible.” It’s a message as humbling as it is hopeful: remembrance that an ideal world will always be in progress, jockeying between those wishing it to stay constant and those wishing for its transformation.

Revolution is forever. The ideal world will always be a moving target, but touchable.

And on that day, I believed him.

Marcus Harrison Green is the editor of the South Seattle Emerald. His column appears the last week of every month.