On Friday, March 2, when a collective of majority white-identified protesters took to the street in solidarity with the No New Youth Jail Campaign and demanded that King County Executive Dow Constantine shut down construction of the new detainment facility at 12th and Alder, we expected the action to end in arrest. When six other people and I locked our arms together in metal tubes and purposefully obstructed traffic in order to publicly confront Constantine at a fundraiser for Senator Patty Murray, I knew that I was breaking the law and I was prepared to be arrested.

Although I fully expected that to be the outcome, the purpose of the action was not to spend time in jail. Rather, it was to break the law in order to bring attention to hypocrisy of Martin Luther King County officials, particularly County Executive Constantine, who claims a commitment to a goal of zero youth detention while simultaneously spending hundreds of millions of dollars erecting a new jail to cage those same children. The No New Youth Jail Coalition is a prison abolitionist movement made up of over 60 community organizations—most of which are POC-led—such as End the Prison Industrial Complex (EPIC) and Youth Undoing Institutional Racism (YUIR). For the past six years, they have been fighting fiercely against the facility’s construction and advocating for a world without prisons, one where justice work will be community-based, restorative, and trauma-informed.

It’s clear that county leadership has never been fully committed to their stated goal of zero youth detention. In a Q13 interview on the day of the protest, Constantine said, “Ultimately we want to upend the system so that instead of talking about alternatives to detention, we are talking about detention being the alternative of last resort.” But detention as a last resort is still kids behind bars; still traumatic for young hearts and minds. Right now, there are only about 50 youth in detention per day, yet Constantine has helped design a facility with more than double that capacity. And although King County has reduced the amount of youth in detention by over 70 percent in the past 10 years, the decrease has disproportionately benefited white youth. As the county states on its own website: “As the overall number of youth in detention has gone down, the proportion of black youth in detention has gone up. Black youth make up about 10 percent of the county’s total youth population, but they now make up almost half of the detention population on any given day.”

The fact that the county can state this so plainly without facing an outpouring of rage is emblematic of how easy it is for white leadership to compromise in ways that endanger the lives of black and brown children and fortify their own power structures. While stopping the construction of this youth jail was the goal on Friday, this is about much more than one youth jail. It’s about the entire criminal justice system, from beat cops over-policing neighborhoods of color and district attorneys who slap people of color with more serious charges than their white counterparts who commit the same crimes to judges who selectively enforce penalties and prisons where corrections officers enforce greater consequences based on skin color.

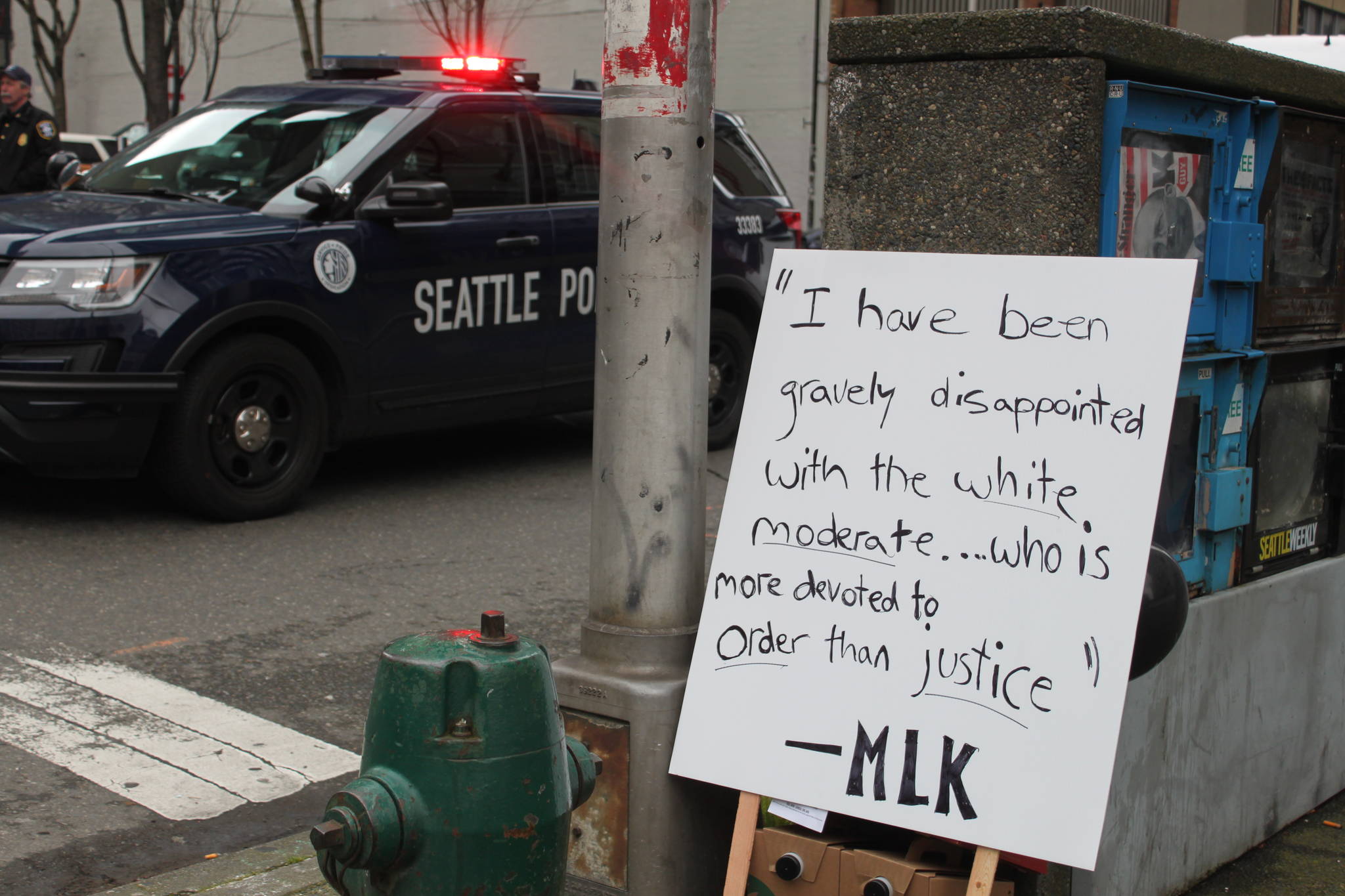

Take, for example, the behavior of police during our action on March 2. Although the Seattle Times reported that no arrests occurred because of the police force’s respect of our first amendment rights, and although we were not on private property, it’s hard to imagine that this respect of free speech would have played out in quite the same way if were weren’t a group of about 50 white people. We knew that the color of our skin was an inextricable part of our escalated tactic, and we used that knowledge to our advantage, although even we didn’t know the depth of bias we’d experience. When the cops arrived 30 minutes into our lockdown of 4th Avenue, they simply sat in their cars. When we walked forward to take one of the busiest downtown intersections, they helped block side streets and cleared away stalled traffic. Their formation was docile, and there was no riot gear to be found. When we were told they had pepper spray, everyone stiffened for a moment, but then they just stood in a polite line along the intersection, chatting and laughing amongst themselves. When a dozen or more bicycle cops arrived, we figured their strategy had changed and they were getting ready to engage. But as we stood and marched down 4th Avenue to confront Constantine, they escorted us—blocking intersections instead of our bodies. In fact, in the six hours that I stood, walked, sat, and laid in the streets at the center of seven locked-down protesters, I wasn’t even approached by a single officer.

Throughout our lockdown, the police treated us with undue, unwarranted respect, as if the traffic delays we caused were as routine as those caused by a permitted parade. Again, let me be clear: I didn’t want to be harassed by cops. Nobody wants that. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned working in movement spaces, it’s that when events are not majority white, cops get frothy with anticipation. They are on high alert, instigating people to step out of line or make a wrong move. They’re not leaning against lamp posts, checking their phones, or escorting protesters to their next location. Instead, their motorcycles bite at the ankles of peaceful protesters, their flashbangs terrify crowds, and their use of chemical weapons keeps the community weeping.

The behavior of police on that Friday underscored even further what we already know: The criminal justice system protects white people while criminalizing people of color, and there is no amount of training that will solve the problems of policing. This disparity was made evident that morning. Our protest was organized and held not just by white people, but by white people with the added privilege of education and relative wealth. In 2014, the Department of Justice ruled that the biased policing of the Seattle Police Department was patterned, ongoing, and in desperate need of reform, but the ongoing racial bias is blatant. Furthermore, as our protest group began appearing on the home pages of media across the region last week, we knew that our risk of arrest was diminishing, because the police want to be portrayed as benevolent enforcers, and that the optics of their axes cutting us apart would not work in their favor.

Protesting is one of the rights that allows human beings to fight for what we believe in, and our country protects it via the First Amendment. It is one of the ways we use our voices to powerfully push back against systems that are not working for us. All people are entitled to this expression of free speech, but not all people are treated equitably as they engage their rights. This becomes crystal clear when an action taken by several dozen white people, and this is what connects our single action to a larger visionary movement that celebrates the human dignity of all people.. The criminal justice system will never protect communities of color: not in the streets, not in the courtrooms, and certainly not through mass incarceration. It is our job as white people to tear down the violent systems that we benefit from and that are sustained by our silence.

This movement is not just about building a friendlier detention center for children. It is about listening and responding to what communities most impacted by racism and incarceration actually want and need to prevent children from ever touching the criminal justice system in the first place. It is about redistributing the hundreds of millions of dollars going into the youth jail construction to programs rooted in and led by communities of color who are already working, with minimal funding, to create vibrant futures for their youth. It is about imagining and creating a world where people aren’t struggling to feed and house families while the county invests millions in a detention center that targets and harms low-income communities of color. We want a world where we can serve people not with lengthy sentences in jail cells, but with support and services that allow them to live fully dignified lives.

Youth detention is a failure of policy and imagination. It is not only unconscionable to build a new youth jail, it is also our obligation to close the youth detention center that’s currently in operation. I know state law mandates a youth detention center in every county, but this law fails to uphold basic public health standards and further enforces a white-dominant power structure. So I’m telling Constantine that sometimes—whether by protesting in the street or refusing to abide a state-sanctioned requirement—the only way we can serve justice is by breaking the law.