Two weeks ago, Alyson Kennedy, 2016 presidential candidate for the Socialist Workers Party, toured Seattle—as any left-leaning politician is wont to do. She spent several days knocking on doors in the city and region, focusing particularly on working-class neighborhoods, chatting with disgruntled voters about the impact of the 2008 recession, unemployment, low-wage work, and the U.S.’s seemingly endless involvement in wars in the Middle East.

The Socialist Workers Party (not to be confused with the Socialist Party, or the Socialism &Liberation Party) is not particularly well-known, nor are its candidates for president of the United States. But “a number of workers told me they were really happy to find out that the Socialist Workers Party was running,” Kennedy says. “They didn’t know about it because we’re a small party. The news only covers Clinton and Trump.” And surprise, surprise: “Many voters told me they didn’t like Clinton or Trump,” she says, adding with a laugh: “ ‘They’re both rotten!’ You get that a lot . . . a lot.”

As a result, perhaps—and because the SWP is explicit in its unflagging support for the working class—“Many people told me they would vote for us.”

This is not Kennedy’s first rodeo; she ran as the SWP’s vice-presidential candidate in 2012 and 2008. But that hasn’t made her candidacy very visible. In Washington state in 2012, the team garnered just 1,205 votes, or 0.04 percent of the total count, and this year (as in previous years), SWP presidential candidates are printed on the ballot in only a handful of states. Kennedy estimates that it’s about seven this time, including Washington, Tennessee, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Louisiana.

So, no, winning the presidency is hardly the group’s goal. “The main reason we’re running in this election,” she says, “is it gives us a big way to get these ideas out to working people”—ideas, for instance, about overthrowing an unjust capitalist system, or about how even the most successful minimum-wage fights may not result in incomes that keep pace with the costs of living. “We say vote for the Socialist Workers Party in this election,” she says, not to elect them, but on democratic principle. “It’s very important. It’s a protest vote.”

Arguably, in this particular election—and particularly in Washington—we could see quite a few “protest votes.” The only two candidates with a snowball’s chance at the White House are breaking records in voter disapproval. In a state that voted overwhelmingly for Bernie Sanders, has comparatively low barriers to third-party ballot access, and votes consistently Democratic by a wide margin (making voting on principle a safe bet), it seems possible that more voters could turn to idealism this year, and go rogue.

“We think it’s better to vote for what you’re for and not get it,” Kennedy says, “than vote for what you’re against.”

According to a Washington Post-ABC News poll from earlier this summer, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are now, officially, the most-hated major party presidential candidates since 1984. A whopping 70 percent of respondents had an unfavorable view of Trump in June, the poll found, 56 percent of whom felt this way “strongly”; 55 percent of respondents had a dim view of Clinton.

In some parts of Washington, those numbers could be similar. After many Washington voters went full-throttle Bernie—he won 72.7 percent of the vote at the Democratic caucuses in the spring—then watched the Democratic nomination slip from his grasp, they’re upset. (Or, as one supporter at Senator Pramila Jayapal’s primary election night party put it: “People are pissed about the Bernie shit.”) Although most Washington voters go Democrat, and, as recent polls show, the state should be a breeze for Hillary, Washington does have a reputation for supporting third-party candidates in greater numbers than do other states.

“Nader in 2000, Perot in 1992, John Anderson in 1980, Robert LaFollette in 1924, Teddy Roosevelt in 1912, all did much better in Washington than they did nationally,” says Todd Donovan, professor of political science at Western Washington University. That “likely reflects weaker ties to political parties here, and our populist roots.”

Since 2008, for instance, Washington has held a “top-two primary,” meaning the top two vote-getters in most races will advance to the November election regardless of party affiliation, making it more possible for voters to opt for the person instead of the party. The top-two system doesn’t apply to the presidential race, but Washington also has one of the most accessible ballots in the country for presidential hopefuls—just 1,000 valid signatures are required to gain access. California, by contrast, requires 178,039. Likely because of this, despite its low returns, the SWP has appeared on the ballot in Washington in almost every presidential election since 1948. In total, seven presidential candidates will appear on Washington’s ballot. Many of them, like Kennedy, plan to actively campaign in the state.

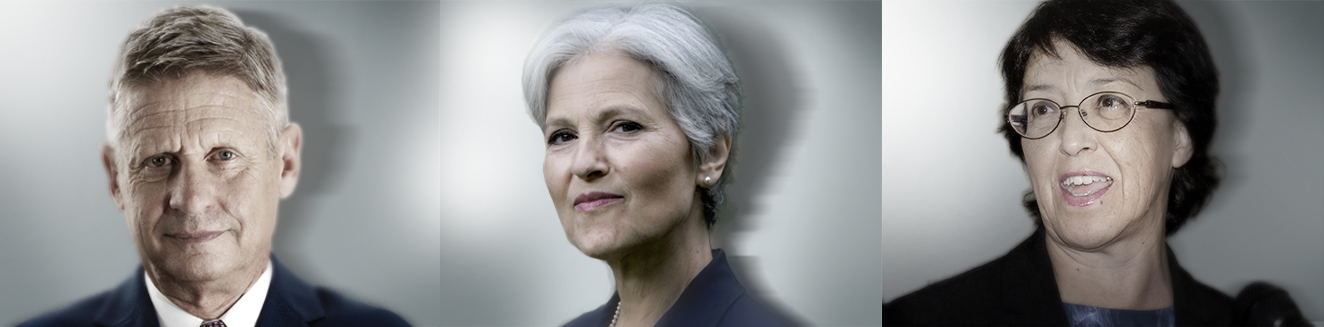

That said, only two candidates on the state docket this year have any chance of giving the two-party system even a very short run for its money: Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson, the only third-party candidate on all 50 state ballots, who still could, theoretically, garner enough support to make the presidential debates for the first time since Ross Perot in 1992 (the Aleppo gaffe could actually have helped him in the polls, he argues); and Green Party candidate Jill Stein, on the ballot now in 45 states and eligible for write-in status in three more. Both Johnson and Stein are now polling higher in Washington than most other states in the nation.

“Third-party candidates tend to be supported by people who don’t identify strongly with a major party,” says Donovan. While these votes are likely a form of protest for many people, he says, they shouldn’t necessarily be seen as leaches on mainstream candidates’ vote totals.

“Lots of Perot and Nader voters said they just wouldn’t have voted if those candidates were not on the ballot,” he says. Small chance they would have voted for Clinton or Trump, either. n