When 30-year-old Steve Titus was arrested for the rape of a teen girl in 1980, he told Port of Seattle police they had the wrong man. They did. But the seafood-sales supervisor was convicted the following year and faced a sentence of up to life in prison. Months later, the actual rapist was arrested, and Titus was vindicated. The stressful ordeal would nonetheless mete out a punishment more severe than Titus could have received in court—his sudden death five years later.

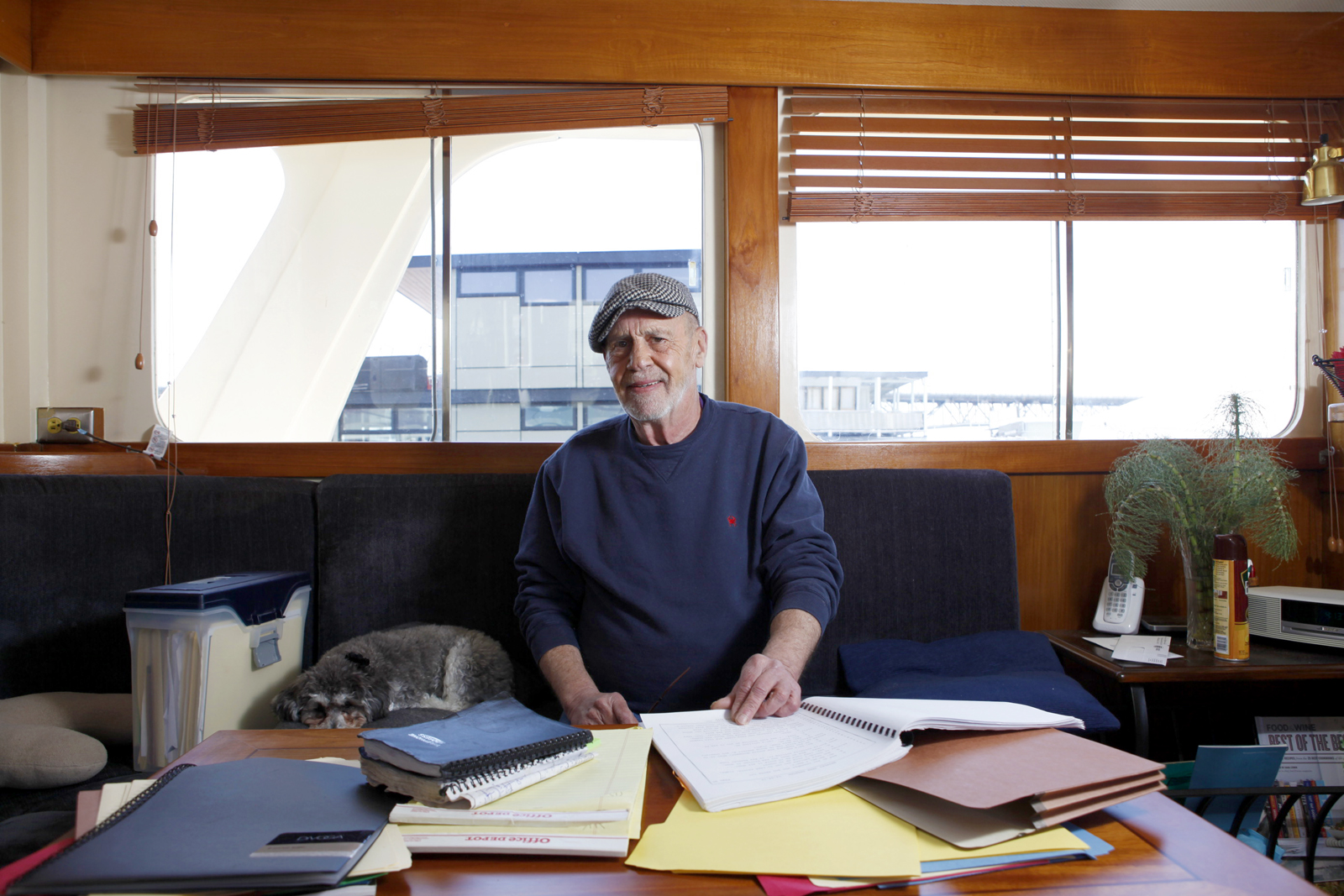

“These things just don’t happen accidentally,” Paul Henderson says, sorting through a box of legal files. “There’s always an element of misconduct.” The ex-journalist and private investigator stops to think about that, and puts down an old Titus case file. Rubbing his stubbly beard, Henderson turns and begins to pace across the inlaid deck of his boat-home, a 49-foot Grand Banks Alaskan tied up on Lake Union in Fremont.

Police, prosecutors—“They’re actually able to sleep at night knowing they’ve convicted an innocent man,” he says, voice rising to a bellow. “They rationalize it. They say ‘I didn’t convict him, the jury did!’ They said that about Titus.”

In March 1981, a King County Superior Court jury found Titus guilty of first-degree rape. While awaiting sentencing, Titus contacted Henderson, then a reporter for The Seattle Times, claiming to be innocent of the crime, the sexual assault of a 17-year-old hitchhiker near Sea-Tac Airport. Henderson was hooked by Titus’ sincerity and the fact that police never explored any of his alibi details or interviewed his witnesses. But the reporter was wary, and told Titus he’d drop the story if he caught the sales exec in a lie.

The evidence against Titus seemed solid enough: The victim identified him in court, and Port police, acting on a tip, stitched together a series of events and eyewitness testimony that linked Titus and his car to the crime scene. Henderson began looking for the kind of details he would spend the next three decades seeking in such cases—contrary evidence and testimony that police and prosecutors had missed or ignored, sometimes purposely. Within weeks, he learned that the victim’s memory of her attacker was hazy, and that she’d been steered by police to identify Titus as the perpetrator. Among other conflicts, there were clear differences between the victim’s description of the rapist’s car and Titus’ vehicle. Henderson also learned a detective had adjusted event times on his report to counter Titus’ alibi: Running his own stopwatch checks, the reporter discovered it was impossible for Titus to have been at the crime scene at the time of the rape. This was crucial evidence, there for the cops to find had they been seeking it.

Confronted with the discoveries, then–King County Prosecutor Norm Maleng dropped the charges against Titus in June 1981. Shortly after, the man who committed the crime, a serial rapist named Edward Lee King, was tracked down. Bearing only a slight resemblance to Titus, King was later convicted and sentenced to 30 years for four rapes, including that of the teen hitchhiker. Henderson, a bar-crawling crime reporter who kept a six-pack in his locker at the police press room where he sometimes slept under a pile of newspapers, won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Bainbridge Island writer Jack Olsen ultimately captured the exoneration saga and King’s sociopathic life in a 1992 best-seller, Predator.

Titus, though, was left medically stressed and financially devastated by the wrongful conviction. He sued the Port for damages, but a few months before the scheduled start of a 1986 civil trial, he died of a heart attack. He was 35. His parents later settled with the Port for $2 million in damages to be paid over 20 years. The year after Titus died, so did the Port detective who had helped wrongly convict him, Ronald Parker. He too suffered a heart attack. He was 43.

King County Deputy Prosecutor Christopher Washington, who had successfully prosecuted Titus, saw no need to apologize about getting it wrong. He was pleased that justice had prevailed, he said. “But I don’t make the decision on guilt or innocence. The jury does that.”

The jury does that mistakenly much too often, Henderson has since discovered. He quit the Times a month after Titus’ death and became a highly sought private investigator with a low boiling point for injustice. Today, at 74 with two marriages and two careers behind him, the teetotaling PI is semi-retired after three decades of freeing wrongly convicted felons—at least 23 by his count—across the U.S. and Canada.

“In almost every case I worked on, those convictions could have been avoided,” Henderson says in the gruff baritone that has persuaded a legion of confident eyewitnesses to change their tunes when confronted by the findings of his investigations. “There was a distinct absence of fair play.”

Unfortunately, there’s a demand for last-resort investigators like him, scouring the countryside for long-gone witnesses or accusers, knocking on the doors of old hotels in St. Louis, wandering through trailer courts outside Dallas, chasing down dead leads in a Spokane flophouse. Since 1985, Henderson has worked for New Jersey–based nonprofit Centurion Ministries, which receives 1,500 letters each year from U.S. prisoners claiming to have been falsely convicted. In three decades, the organization has freed 50 wrongly imprisoned men and women.

Henderson’s last case before he retired from full-time sleuthing last year took him to 14 states. “I hate flying,” he says. But he loves a mystery. He and Centurion’s mission is to dig for new evidence in dust-covered case files. The sleuthing almost always requires shoe leather to round up hidden or undiscovered facts—a strategy different from that of another famed exoneration group, the New York–based Innocence Project, which focuses on retesting crime-scene DNA and has helped reverse more than 300 convictions nationally. A local arm of the project, Innocence Project Northwest, operates out of the University of Washington and has chalked up eight notable reversals.

Courts may overwhelmingly grind out fair verdicts, Henderson says, but some of those decisions are flawed or flat-out wrong, sending the legally not guilty and the plainly innocent to jail or prison. In Washington state alone, according to compilations by the National Registry of Exonerations and similar organizations, more than 50 people have been wrongly convicted of felonies over the past four decades. They include accused robbers, rapists, and child molesters who in fact did not commit the crimes (click here for a full list of Washington’s absolved convicts). Released after new evidence was discovered or when advanced DNA-testing procedures confirmed they were innocent, some of the wrongly convicted have sued and received compensation for their imprisonment.

Others, such as Alan Northrop—who served 17 years after he and a second man were wrongly convicted of rape in 1993—received nothing. Northrop has testified for three years in a row in Olympia in favor of a bill that would allow exonerated prisoners to file for compensation—$50,000 for each year of imprisonment (same as the amount given wrongly convicted federal inmates) and up to $75,000 in legal fees.

The third time was the charm, however, when the bill was approved by the legislature last month and sent to Gov. Jay Inslee for his signature. Northrop could receive more than $900,000 in compensation, which can be approved by the state Attorney General or through a court hearing where petitioners must prove “actual innocence” of the crime. Money will come from a new state liability fund, which can also provide education aid and pay past child support for those who qualify. The state estimates that at least 15 wrongly convicted former inmates are likely to file claims in the first three years, and one to two each year thereafter. The bill, sponsored by Normandy Park Democrat Tina Orwall, requires taxpayers to “redress the lost years” of those “uniquely victimized” by wrongful prosecutions.

“About time!” says Henderson. Washington will be the 28th state to adopt a compensation law.

At least a dozen of Washington’s wrongful-conviction cases resulted from the country-wide hysteria over alleged child-care abuses and child-molestation “rings” in the 1980s and ’90s. Most memorably, in the mid-1990s, an investigation by Wenatchee police and state child-welfare workers resulted in the arrest of 43 adults on 29,726 charges of sexually abusing 60 children. Prosecutors had no physical evidence to support the charges, and their key witness was the 13-year-old foster daughter of a Wenatchee cop. The officer, Robert Perez, drove the girl around town and had her point out the homes where she claimed she and other children had been molested. Most suspects were falsely accused, and ended up being released. Eighteen went to prison, but all verdicts were overturned or the charges and sentences reduced. The Wenatchee Witch Hunt, as it became known, led to millions of dollars in wrongful-conviction damages against Wenatchee and Douglas County. Some of the accused are now expected to file for compensation under the new state law.

It was during that time that Ray Spencer joined the state’s legion of the wrongfully convicted. Henderson worked on his remarkable case, and thinks Spencer is Exhibit A in the way the law can be manipulated to convict anyone of a crime he or she didn’t commit. What makes his case stand out is that Spencer, in fact, was the law—a police officer in Vancouver, Wash. Today, 28 years after he was falsely imprisoned for raping his own children, and three years after all charges against him were officially dropped, he’s still in court attempting to clear his name.

“I lived. They didn’t count on that,” Spencer tells Seattle Weekly. “The people who put me away assumed that being a police officer and ‘child molester,’ I would be killed in prison. There wasn’t a day that went by that I didn’t think was my last. But I managed to survive 20 years.”

In the early 1980s, Clyde “Ray” Spencer was considered an arrogant, womanizing motorcycle cop in Vancouver. Spencer allows that he was a womanizer, at least. He was married with two young kids, but took advantage of his good looks to cheat on his wife, DeAnne. Married in 1971, the two divorced in 1981, and she moved to Sacramento with their children, Katie, 2, and Matt, 5. Two years later, Spencer remarried. New wife Shirley arrived with a 3-year-old son from an earlier marriage.

In 1984, while Katie was visiting her dad in Vancouver, Spencer recalls, the girl put her hands between her legs and told Shirley, “My brother does this, my mom does this, my dad does this.” Spencer assumed Katie was being molested, and that “dad” was DeAnne’s boyfriend. “Katie told me, ‘Daddy does it to me,’ ” Spencer recalls.

Spencer, who lived just outside Vancouver, reported his suspicions to the local sheriff’s office and to child-protection and police officials in Sacramento. He also told his Vancouver police superiors he’d reported the claim. California authorities found nothing to pursue, but Clark County did. Sheriff’s Detective Sharon Krause flew to Sacramento, where she questioned the children. Eight-year-old Matt denied he was abused. But Krause reported that 5-year-old Katie gave lurid details of rape—none of which the detective recorded. Krause’s most startling discovery, reported to her superiors, was that the “dad” Katie was referring to was her own dad, officer Spencer.

In January 1985, following an eight-month investigation, the man who reported the possible sexual assault of his daughter was charged with committing that assault. Spencer’s department immediately fired him, and the charges broke up his marriage. Then, more charges: While he was staying at a motel, estranged wife Shirley asked if her son—Spencer’s stepson—could spend the night with him. He obliged. Days later, Shirley told sheriff’s detectives that her son had just been raped by Spencer. After an investigator met and interviewed the son 12 days after the stay, Spencer was charged with raping his stepson as well.

“It was a nightmare,” Spencer says today, “and a lie.” He lost it mentally and sought psychiatric counseling. He was facing altogether 11 counts of rape. Investigators alleged he forced the children to engage in sex acts with each other while he watched.

Two days before his sentencing, he underwent a “truth serum” test with a doctor in Portland—he made no admissions of assaulting his children, the doctor concluded. But Spencer says he was in a vulnerable state from the residual effects of the sodium amytal and the side effects from sedatives he was taking. Foggy-minded, and feeling that his attorney, James Rulli, had not prepared a viable defense—he had failed to interview the children until just a few weeks before the trial—Spencer opted to plead out, hoping for a lesser sentence. In court, the 37-year-old ex-cop entered an Alford Plea: In effect, he conceded the facts would convict him, but he was not admitting guilt.

Thomas Lodge, the sentencing judge, handed down the toughest term he could give—two life sentences plus 14 years. Spencer remembers almost fainting, and a guard helping him to remain standing. He went off to prison in 1985—unaware, it turned out, of many of the relevant facts of his own case.

Word traveled fast at the state Corrections Center outside Shelton. Days after arriving, Spencer woke up to hear dozens of inmates chanting “Kill the cop in Cell 4.” Spencer spent most of his first year in isolation. Eventually, to distance him from his 14-year law-enforcement background—Spencer had also worked as a federal sky marshal and narcotics officer, and had a bachelor’s degree in criminal justice—the Washington Department of Corrections transferred him to the Idaho State Correctional Institution outside Boise. There, for nearly two decades, Spencer witnessed inmate rapes, beatings, and suicides. He lost teeth in fights to avoid becoming other prisoners’ sex punk. He read 3,000 books. And through a correspondence course he obtained a doctorate in clinical psychology. But his cop background stayed a secret.

“My story was, I was an air traffic controller, out on strike when Ronald Reagan fired us all [in 1981],” Spencer says. “I said I knew people in South America running drugs, and helped them smuggle drugs by boat. I got caught in a shootout and my partner shot a cop. I was convicted of being an accessory. I never wavered on details. It worked for 20 years.”

It might have had to work longer if Spencer hadn’t, after almost a decade in prison, contacted Seattle attorney Peter Camiel and convinced him to take on his appeal. Spencer’s earlier appeal attempts had failed, making it clear he needed new evidence if he was to prove his innocence, or at least show he hadn’t gotten a fair shake in the justice system.

Fortunately, Spencer had someone else who believed in him, a new wife. They had first met in 1968 on Guam when he was stationed there with the Air Force during the Vietnam War. She was a Navy nurse. They dated, but separated after returning to the States. In prison, Spencer found Norma Kohlscheen’s address in Los Angeles and wrote to her. She wrote back. On Guam, he’d asked her to marry him. She’d turned him down. This time she didn’t. They were wed in 1986 in the Idaho prison chapel. She continued to live in L.A.—Spencer’s hometown—visiting and corresponding regularly. She also agreed to help pay Spencer’s legal fees (which would eventually reach more than $250,000). “She worked 70 hours a week at two jobs,” says Spencer. “She never doubted me.”

Attorney Camiel called in the hound, Paul Henderson. In 1999, the private investigator was working for both private clients and Centurion. “Spencer’s was a dig-up-whatever-you-can case,” says Henderson. Over time, he dug up gold. For starters, Henderson learned medical reports existed, hidden from Spencer’s defense, that showed no indications any of the children had ever been sexually abused. Clark County Det. Sharon Krause, he also discovered, had held unorthodox meetings with the Spencer children, interviewing them in unrecorded sessions in her Sacramento hotel room and buying them gifts and candy. She told the children their father was “sick” and that they could help heal him by accusing him of the sexual crimes. He learned that Spencer’s son, who at first denied any abuse, had changed his story under months of questioning, coming up with a fantastic tale: Not only his father but a group of police officers had abused him. Henderson, suspicious about the night Spencer’s second wife Shirley brought her son to his motel room, wondered if that was a setup. He found his answer: Shirley was having an affair with Vancouver Police Sgt. Mike Davidson—the supervising detective on her husband’s case.

Camiel eventually took the new information to Gov. Gary Locke. In 2004, Locke, a onetime King County deputy prosecutor (and today Barack Obama’s ambassador to China), was moved by the findings. His office made its own inquiries to confirm the details, and Locke then commuted Spencer’s sentence. He ordered Spencer released immediately, although he placed him on community supervision for three years. It was a stunning reversal: Locke had freed the longest-ever-held sex offender in Washington state, and for good reason, as he outlined in his order:

Clark County authorities withheld the fact that, despite the allegations of severe, repeated sexual abuse of the children, medical reports showed no signs of physical abuse. While the children recounted that Mr. Spencer had taken photographs of the abuse, no photos were ever found . . . King County Senior Deputy Prosecuting Attorney, Rebecca Roe, a renowned specialist in child sexual abuse cases, [advised Clark County officials of] significant problems with the case, including techniques used with Mr. Spencer’s daughter and resulting inconsistencies in her testimony . . . While denying for eight months that anything had happened, Mr. Spencer’s [son] began to say that his father abused him, after being threatened with a polygraph . . . another troubling fact in the case is that one of the lead detectives investigating Mr. Spencer’s case began having an affair with his wife, Shirley Spencer, during the investigation. After Mr. Spencer’s conviction, the detective left his own wife and moved in with Mr. Spencer’s wife. This detective was also the supervisor of the primary detective [Krause] involved in interviewing the children.

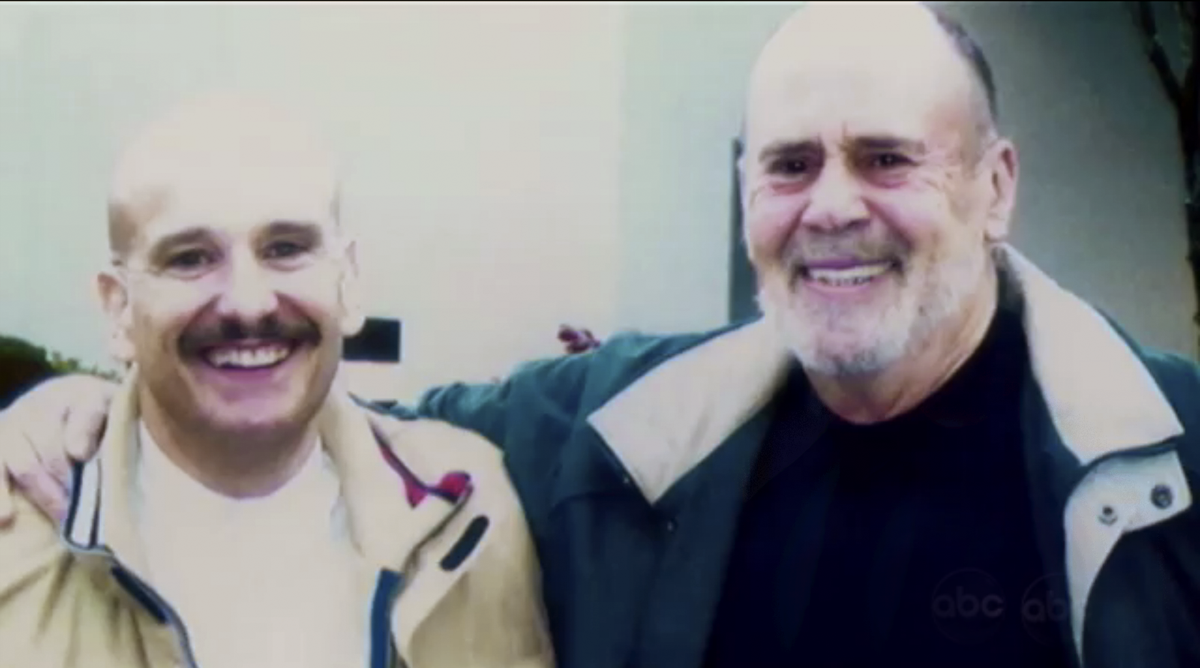

Transferred back from Idaho, Spencer walked out the front gate of the Monroe Correctional Center on December 29, 2004, having spent 7,244 days behind bars (19 years, 10 months, and one day). Henderson was there to greet him, took him to a bank to cash his small prison-labor check, bought him a steak, and dropped him off at a motel on Aurora Avenue in Seattle. The next morning, Spencer recalls, he got up early, went out into the free world, and began to walk until he was exhausted.

As a registered sex offender, he still could not join his wife in California, though she quickly arrived to greet him, returning regularly as they continued their long-distance relationship.

Spencer eventually would reconcile with his two children, now grown and with families of their own. The siblings eventually told Spencer they’d been coached by police. As they grew, the children had trouble remembering Spencer’s alleged abuse, but their mother had told them they were blocking the sordid memories. They now realized, they told Spencer during their meetings, there were no assaults to remember.

“In prison, I went before the parole board five times and told them I didn’t do it,” says Spencer. “They said if I didn’t admit it, I’d die in prison. I told them, ‘Then I’ll die in prison.’ Here was the opportunity for everyone to know the truth.”

His life destroyed by the conviction, and unable to get viable work because of his record, Spencer pushed ahead with a new legal effort to overturn his conviction. At a 2009 hearing ordered by an appeals court, Katie, 30, and Matt, 33, recanted their testimony—or rather the claims of the Clark County Sheriff’s investigators that they’d been assaulted. Under cross-examination, Matt said he, at age 9, had been pressured by his questioners to say he’d been abused. Katie said that as an adult she read over the police reports of the rape and found them untrue. Even as a child, “I would have remembered something that graphic, that violent.” Spencer’s grown stepson refused to change his story, although Katie and Matt testified they never saw him abused.

Relying on the hearing testimony, the state Court of Appeals ruled that Spencer could withdraw his guilty plea, citing the recantations and “significant irregularities” by prosecutors. The state Supreme Court upheld the decision, concluding, among other things, that the affair between Spencer’s wife and the detective “casts a shadow over the entire case.” Reluctantly, Clark County prosecutors, who still believed Spencer guilty, threw out the charges in 2010.

But Spencer wasn’t done. “When this case was overturned,” he says, “instead of the prosecutors saying this was a mistake, they stood down the hallway in the courthouse and gave out a press release, trying to say they didn’t do anything wrong.” At the time, Spencer says, “I told myself that someday, somebody is going to apologize.”

Today, the 65-year-old Spencer is still seeking that apology, along with legal damages. The ex-cop, now head of security at a Los Angeles office complex, filed a lawsuit in 2011 on behalf of himself and his children against Clark County, his ex-wife Shirley, and several of the officials involved in his conviction. Among his claims, according to court records, is that Sheriff’s Detective Krause had in fact videotaped an interview with one of the children, but it was not disclosed to the defense in 1985. Krause, in court papers, says she apparently took the tape home—mixed with other memorabilia—when she retired from the sheriff’s office in 1995. She discovered it while cleaning her garage in 2009, and turned it over to prosecutors.

Spencer claims the video got “lost” because it suggests the child was coached. The 1984 tape shows little Katie, sitting in her mother’s lap, being questioned by Clark County Deputy Prosecutor Jim Peters. In the first part of the video, Peters is unable to elicit any claims from Katie that she’d been sexually assaulted. He shows her anatomically correct dolls and tells her, “This is your daddy and this is Katie—show me what happened last summer, OK? And we can stop all this.” Katie responds, repeatedly, “Nothing happened last summer.” After an unexplained one-hour break in the video, the prosecutor and Katie are shown lying on the floor together, in a friendly face-to-face chat. She then begins to cooperate, taking the two dolls and putting them together in a sexual position.

In his lawsuit, Spencer alleges that ex-wife Shirley and Sgt. Davidson had a “sexual relationship [that] led them to attempt to frame Mr. Spencer.” He also alleges that Clark County investigators altered records to hide the medical reports, and that they falsely advised his employer, Vancouver Police, that he’d failed a polygraph test when in fact the test had been inconclusive.

Ex-county prosecutor Peters, who went on to become a federal prosecutor in Idaho and who is being defended in the civil suit by the Washington State Attorney General’s office, denies Spencer’s accusations that he hid evidence. Peters is also immune from such civil claims, argues his attorney Patricia Fetterly, saying he “exercised reasonable judgment and discretion as an authorized public official.” Shirley, Spencer’s ex-wife, says his accusations of a frame-up are simply untrue; she and Davidson did not become involved until after her husband’s case was concluded, she maintains. Ex-detectives Krause and Davidson deny the claims as well, insisting they acted in the best interest of the children and followed investigative procedures in use at the time. Clark County attorney E. Bronson Potter describes the investigation and prosecution as lawful and proper. A jury trial is currently set for next January.

Inside his Lake Union boat home, Paul Henderson is thumbing through more files—he has dozens of boxes and thousands of pages of documents stored in a closet and a nearby locker. “Wrongful confessions are one of the biggest problems in these cases, and the most difficult to overturn,” he says, recalling Barry Beach of Montana. He was 21, still living with his parents, when he was arrested in 1983 for buying beer for a minor, a misdemeanor. He wound up doing 28 years in prison for confessing to a murder—the slaying of a teen girl—he did not commit, as Henderson’s investigation helped prove. The case was one of many worked on by Henderson that were featured on national TV magazine shows, including 60 Minutes and 20/20. “He was put away by cops who talked him into it,” says Henderson. “The first 48

Hours report on him—they did two—prompted new witnesses to come forward. That’s how he got out.”

Filmmaker Ken Burns, whose 2012 documentary The Central Park Five detailed the wrongful convictions of five Harlem youths coerced into confessing to the 1989 rape of a New York jogger, recently said in a C-SPAN interview that “Unfortunately, [the park rape case] is not unique . . . We read in our papers of someone who has just been released from jail after 40 years or 25 years. It’s prosecutorial misconduct or ‘over-enthusiasm’ or something like that. This is happening too frequently . . . If there is not justice for all, there is not justice for all.”

But wrongful convictions will continue, Henderson says, as long as police and prosecutors are not punished for them. “They should be held criminally responsible, in my view,” he says. “In the 23 exonerations I handled, some of them involved egregious misconduct, including police coercing witnesses into going along with a totally fabricated scenario of a murder. In a Pennsylvania case, the cops sat down like they were writing fiction and got three teenage kids to go along with the confession. But over the years not one cop or prosecutor in my cases who got caught red-handed making up stuff was ever charged with a crime. They were not even demoted.

“You remember what happened to the cop who made up evidence about Steve Titus, don’t you? A few months later, the Port of Seattle named him Officer of the Year.”