A scan of the news suggests the United States has both a crisis of mental health and one of excessive police force. But the two issues are not mutually exclusive, according to mental health experts. For instance, National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Eastside receives at least two calls a month from the family members of people in crisis who had some sort of interactions with the police.

Just last week, NAMI Eastside Director Michele Meaker said that a woman called the center seeking mental health services shortly after an incarceration. During a family gathering where she “wasn’t acting herself,” the client’s husband called 911 to get her treatment at Kirkland’s Fairfax Hospital, but his efforts backfired when the police arrested her in front of her parents and children, and took her to jail instead. Although the woman had had a negative experience with the police, she was also lucky compared to what some struggling with mental health face when interacting with police. According to data collected by The Washington Post, nearly a quarter of people fatally shot by police in 2017 were allegedly experiencing mental distress during the encounter.

“Not all these calls end in death,” said Meaker, “but we have quite a few of these calls that have ended in criminalization of those family members who are affected by mental illness, and they’re struggling.”

One month after the passage of police reform measure House Bill 3003 (which modifies the provisions of Initiative 940), some of the legislation’s key advocates—including Meaker—are pushing to the spotlight the issue of police violence against people with mental health illnesses. House Bill 3003, which will be enacted on June 8, mandates that police receive de-escalation, mental health, and crisis intervention training. Meaker hopes that the law will help decrease negative interactions between police and people in mental health crises, which she noted is all the more necessary following the fatal police shooting of Pierce County resident Billy Langfitt on March 16. The unarmed Spanaway man was suffering from a mental breakdown when his girlfriend called the police. A Pierce County sheriff’s deputy who responded to the call shot and killed Langfitt, according to The News Tribune.

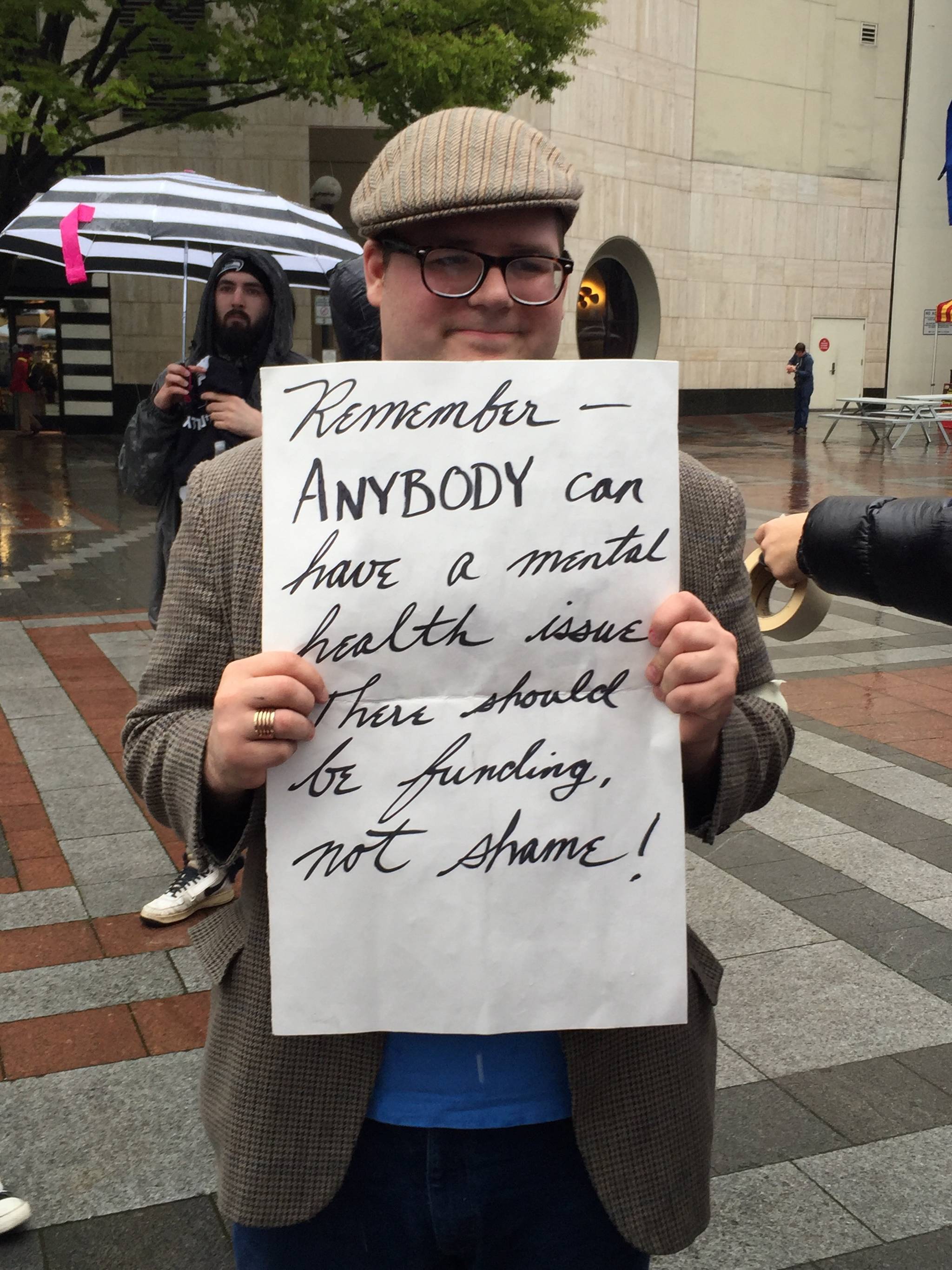

On Saturday, April 14, Meaker joined the grassroots movement Not This Time, ACLU Washington, and other civil rights organizations to commemorate Langfitt at Westlake Park. About one hundred people gathered to hear the perspectives of four families of people who were fatally shot by police while they were in mental health crises. At Saturday’s rally, advocates celebrated the passage of police reform legislation and requested additional funding for mental health police training. “I just wanted to make sure we focused … some special attention on folks that are in crises, or folks who have some disabilities,” said Not This Time founder Andre Taylor, the brother of Che Taylor, who was killed by Seattle police in 2016.

I-940 and HB 3003 grew out of police reform adovocates working for years to change a 1986 law that had safeguarded officers from prosecution if they killed someone on the line of duty “without malice and with a good faith belief that such act is justifiable.” The law made it nearly impossible to prosecute a cop. A 2015 Seattle Times investigation found that only one officer was charged out of the 213 fatal police shootings between 2005 to 2014. The new legislation removed the “malice” requirement, and it also expanded the definition of “good faith” by requiring that offending officers meet an “objective” test. According to HB 3003’s text, the objective good faith test is met when a reasonable officer “would have believed that the use of deadly force was necessary to prevent death or serious physical harm to the officer or another individual” in light of the facts know to law enforcement at the time.

Now that the legislation has passed, Meaker thinks that NAMI Eastside could play a critical role in reducing the amount of negative police interactions with the community by providing law enforcement with resources and training. But Meaker said she believes that the momentum and advocacy that I-940 and HB 3003 built is just one tool. “The greatest impact we can have is to have greater access to services for people who are experiencing mental illness,” she said.