ECONOMICS

Katie Wilson, general secretary of the Seattle Transit Riders Union—a pro-transit group—says taking on corporate interests is daunting, but is of central importance to the goals that groups like hers hold.

“If we’re going to really create a society that’s equitable, we as a community need to be taking ownership of services, not just regulating how corporations provide those services,” she says. The current economic structure—capitalism—has left a lot of people on the outside, she says, prompting conversations about a better way. “I think there is increasing interest in non-market solutions to things like the housing crisis.”

On that point, there are a number of ideas on how the city can rein in housing costs—Wilson notes community land trusts as one idea, and a push by South Seattle residents to get a new elderly-housing development built by the city as another. But in the leftist vanguard, the most popular is rent control.

By anyone’s telling, the path to rent control is a hard one. In 1981, the state legislature passed a law banning the practice statewide, meaning that before any kind of rent control was passed in Seattle, it would need to get approval from lawmakers across the state.

That said, there is evidence that the policy has support in Seattle. A 2015 City Council resolution called on the legislature to repeal the ban. With a room full of activists waving red signs bearing messages like “We need rent control” and “The rent is too damn high,” the Council voted 8-1 to pass the resolution, when just a week before it appeared as though it wouldn’t even get a vote. “Mass pressure forces establishment to concede,” Councilmember Kshama Sawant asserted in a press release, not incorrectly. And more support could be on the way. Councilmember Tim Burgess ultimately voted for the rent-control resolution, but he was also in the lead of toning down the language in it. Burgess is not running for re-election this year, and the former director of the Tenants Union of Washington, Jon Grant—a strong proponent of rent control—is running to replace him as a democratic socialist. Mayoral candidate Nikkita Oliver has also made rent control a plank in her candidacy, drawing sharp contrast with Mayor Ed Murray, who doesn’t think rent control is realistic.

Just like those advocating for rent control or better transit, Upgrade Seattle’s ultimate goal is to make Seattle more affordable and equitable—in its case by providing cheaper, better broadband that ensures everyone in the city has access to it. And just like those other causes, their biggest hurdle is those who benefit from the economic structure as it stands.

“We’re all really committed to making Seattle a better place to live, but also a just place to live,” Devin Glaser, policy and political director of Upgrade Seattle, says of the new left. “What we’ve seen is a lot of behind-the-scenes pressure in the form of PAC spending, lobbying. Comcast has been the number-one contributor to various political campaigns. What they’re really trying to do is push against the attack on their bottom line.” To fight back, Upgrade Seattle has also used the power of the people, seizing on the fact that Comcast is really unpopular.

Upgrade Seattle has thus made a point of getting every City Council candidate on the record about public broadband, and have recently seen some measured victories—specifically the addition of municipal broadband to the city’s 20-year master plan (efforts to actually fund it have been less successful). Glaser says he only expects Council support to increase as more new members—who haven’t been subjected to years of Comcast lobbying—come on board.

Efforts like municipal broadband or improving transit would require public funding, which is the motivation behind the Transit Union’s new effort: to create an income tax in Seattle on those making more than $250,000 a year. Uniting under the banner of “tax the rich,” the effort is being pitched as a way to move Seattle away from its reliance on sales and property taxes, both of which disproportionately affect the poor. Regressive taxation, Wilson says, makes it difficult right now for groups like hers to get behind tax measures. “As a left, social-justice organization, it’s hard for us to keep supporting these measures that are burdening the people who we are trying to represent,” she says.

While the Transit Riders Union, along with the Economic Opportunity Institute, is leading the push, it has quickly amassed a sizable coalition of supporters, including labor unions, climate activists, and Upgrade Seattle. The tax, Upgrade Seattle’s Glaser says, is a perfect melding of otherwise disparate political causes, and speaks to the cohesive nature of this political movement.

“The more I get involved in Seattle politics, the more I testify, I keep seeing the same faces. There is a lot of overlap, the end goals are the same: to make the city a wonderful place to live.” DANIEL PERSON

JUSTICE

#BlockTheBunker and #NoNewYouthJail are two of the most concrete examples of the political results achieved by the Black Lives Matter movement, and their brazen tactics have carved a new path for radical left activism in Trump-era Seattle.

Rewind to 2012. King County voters approved a tax measure to fund a brand-new, $210 million Children and Family Justice Center (CFJC) that would include a 212-bed youth detention facility to replace the current one, which is aged and leaky but functional. Proponents of the new facility argued it would be designed as a more humane space, and would save money on repairs in the long run. But ever since the measure passed the ballot, local anti-racist activists rallying under the banner of #NoNewYouthJail have fought the new facility at public meetings, in the press, at ambush press conferences, and outside elected leaders’ homes. They demand that instead of building a new jail, the county should pay for community-based social services and pre-trial diversion programs to interrupt the feedback loop of poverty, racism and incarceration.

The attempt to derail an already-approved county project seemed quixotic at first, but has slowly gained traction and concessions over the years. The number of planned jail beds has been cut nearly in half, and those that remain are in rooms that can be converted to other uses if the number of youth jailings at the city and county level continues to decrease, as it has been for years. But opponents of the new facility argue that any capital investment in cages for children will inevitably lead to more children being caged—or as lawyer and mayoral candidate Nikkita Oliver puts it, “You put your money where you put your kids.” Earlier this year, some elected leaders in city and county government began to warm to this argument in noncommittal public statements.

Last year, #NoNewYouthJail found a sister movement: #BlockTheBunker. While moving forward with a long-contemplated project to replace an aged, cramped, occasionally flooded police station, Mayor Ed Murray’s administration decided to bump the price tag up to $160 million. If built, The Seattle Times reported, it would be the most expensive police station in the country. At the same time, rents across the city and region were exploding, as was the scale of homelessness.

The contrast between the police getting a Cadillac cop shop and the 99 percent getting lip service proved a powerful framing device for opponents of the new North Precinct. Critics dubbed it a “bunker” for its earthquake/bomb-resistant design. The pithy, concrete moniker was a marketing success on Twitter and Facebook (where organizing happens). Huge, passionate, sometimes furious crowds began to fill Seattle City Council meetings’ public-comment sessions; dozens of speakers, one after another, urged, scolded, criticized, berated, pled with, politely asked, and occasionally verbally abused councilmembers, week after week.

The Council bellowed, then buckled, then broke. Led by president Bruce Harrell, Seattle’s legislators triumphantly announced in August that they would reduce the price tag of the new police precinct from $160 million to $149 million. This news only further incensed opponents, who clarified that they didn’t want a smaller police station; they wanted no new police station, and for the project’s budget to be spent on affordable housing and social services instead. After a little stammering, the Council and mayor agreed, and put the project on indefinite hold. The new North Precinct isn’t dead, but it’s dormant, and a week after Trump’s election, the Council earmarked $29 million of that budget to pay for affordable housing.

While drug users and status offenders are easy enough to divert, opponents of the new youth jail have sometimes struggled to articulate alternative plans for dealing with the small number of young people who threaten, at least temporarily, themselves or others. But Oliver, who has worked with jailed youth, distinguishes between “incapacitation” and incarceration. “Jails are, by nature of the way they’re constructed in this country, not therapeutic, not rehabilitative, do not provide restorative opportunities,” says Oliver. “If we were to actually create spaces where young people can care for their body, care for their mind, care for their spirit—and in those instances where a young person does need to be separated from the environment that they’ve been in, that’s brought them to this hard place, and they can be brought to an environment that allows them to take care of themself—that’s a therapeutic space I would support.”

The new youth jail/CFJC is on course for construction to begin this year, but given the recent signs of movement from some elected leaders—and Oliver’s palpable threat to incumbent Ed Murray—its completion is no longer a foregone conclusion. CASEY JAYWORK

ENVIRONMENT

One of the very first articles Seattle-based Lakota activist Matt Remle wrote in support of the protests at Standing Rock—right after the Sacred Stone Camp was erected in April 2016—was about divestment. On Last Real Indians, a Native news site where Remle is a frequent contributor, “I wrote about ways you can support the fight against the Dakota Access pipeline,” he says, and high on his list even then was pulling money from any banks that had funded the project. “That’s been a part of the strategy for a long time, to get folks to divest. It hasn’t gotten that much attention until recently.”

Last spring, the Standing Rock Sioux were still several months away from capturing the world’s attention. But last fall, after their battle had exploded in the media and in activist circles, Remle saw an opportunity. The City of Seattle moved a whopping $3 billion in and out of bank accounts it held exclusively with Wells Fargo, a financial institution that had fronted DAPL some $467 million. Getting Seattle to pull its money out of Wells Fargo could be a huge financial and public-relations hit for the bank—and then, perhaps, the pipeline. Remle drafted a proposal, brought it to Councilmember Kshama Sawant’s office, and by December 12 of last year, Sawant had introduced an ordinance proposing that the city close its Wells Fargo accounts.

Divestment, as Remle and activist Gyasi Ross put it in another post for Last Real Indians, is the “next stage in the fight” against DAPL and all kinds of pipelines. Put aside your moral and environmental arguments, they advise, and just “Hit them in the pockets, which is all corporations care about.”

It seems, little by little, to be working. Since the inauguration of Donald Trump, “there’s been a huge shift, just in the energy and the willingness of people to engage,” says Alec Connon, a member of 350 Seattle who has been toiling for the past several years on every local climate action you can name. The climate group has added thousands of people to its mailing list since the election, and so many people now attend meetings that they’ll soon have to find a larger meeting space. And, since November, many of those people, led in particular by Remle, Connon, Muckleshoot tribal member Rachel Heaton, and Alaska Native Millie Kennedy, have been doubling down on a single idea: DIVEST.

The Defund DAPL Seattle Action Coalition, now rebranded as Mazaska Talks (from the Lakota word for “money”) took to the streets, but also put an enormous amount of pressure on City Hall. They packed Council chambers, spilling into hallways and stairwells and neighboring meeting rooms; they crammed public-comment periods and Councilmembers’ e-mail inboxes. They even garnered the online support of activists nationwide—some 13,000 people from across the country RSVP’d on Facebook for a Seattle finance-committee meeting, and councilmembers received some 200,000 Tweets in support of the ordinance leading to the final vote. On February 7, Seattle became the first major city in the country to decide to move its money from a bank due, at least in part, to its ties to the Dakota Access pipeline.

Seattle’s move “really has had a ripple effect,” says Connon, pointing out that following the vote, he and other activists set up a series of conference calls with hundreds of organizers from across the country, and eight other cities, from San Francisco to Missoula to Washington, D.C., have all since brought forward similar legislation.

Riding the #DefundDAPL success, Connon, Remle, Heaton and many others then went after the Keystone XL pipeline, too (blocked by Obama, then greenlighted by Trump). Thanks again to activist pressure, Kshama Sawant, and a sympathetic City Council, on April 3 the Council also unanimously approved a resolution that prevents the city from banking with a financial institution that funds Keystone XL or any TransCanada oil project.

Next up: the city’s $2.5 billion pension fund. That too has gained traction: After six weeks of activism, co-led by Connon, on April 11 Mayor Ed Murray sent his firm recommendation to the board that oversees Seattle employees’ pensions that it divest from coal immediately and consider divesting from all fossil fuels, too. On April 13, the board decided to study the idea. A decision is expected this summer.

For Connon, who has been working on fossil-fuel divestment efforts for years, climate change means global catastrophe, and divestment only makes sense—even economically.

For Remle, whose aunt, LaDonna Allard, founded the Sacred Stone camp, and who has been fighting the Dakota Access pipeline “literally from day one,” one of the most beautiful things about the movement is its ability to share cultural knowledge—sacred Lakota knowledge that resonates with all kinds of people. “Who would have thought [mni wiconi] is used around the world now!” he says, laughing. Across the globe, “People are saying: ‘Water is life.’ ” SARA BERNARD

EDUCATION

In Seattle, community organizing to fight institutional racism in public schools and upend the whitewashing of U.S. history curricula had been going on long before Donald Trump took office in January. Spearheaded by two allied but separate fixtures in local lefty education activism—social justice-minded educators in Seattle Public Schools and indigenous activists from the local Native American community—these two movements have scored a stack of recent victories through collective action.

Seattle Public Schools activists trace the origins of their movement to widespread mobilization against standardized testing several years ago. “I think you have to go back to 2013 to understand some of the major shifts that have happened,” says Jesse Hagopian, a longtime history teacher at Garfield High School and a key figure in the movement. In 2013, Hagopian, along with the rest of the faculty at Garfield, refused to administer the Measures of Academic Progress (MAP) standardized test, a product of the George W. Bush-era “No Child Left Behind” policy that would have tied teacher evaluations to students’ test scores. They argued that the MAP test was not an accurate measure of students’ learning and aptitude, and that it puts English-language learners and people of color at a disadvantage. This boycott spread to other schools throughout Seattle, and, ultimately, the SPS Board decided to scrap the MAP test. “That [victory] emboldened social-justice educators,” Hagopian says.

Since then, Seattle organizing has gotten bolder, with a more explicit anti-racist edge. In the fall of 2015, Seattle Education Association, the union representing all Seattle public-school teachers, voted to go on strike during contract negotiations with the school district. In addition to expected demands (like better pay), the union called on the school district to combat disproportionate discipline rates. After the five-day strike, the district caved and agreed to the union’s demands, including a commitment from the school district to establish committees at 30 Seattle schools to address racial-inequity issues. More recently, in the fall of 2016, schools across Seattle held “Black Lives Matter at School” events, during which teachers wore BLM T-shirts to class to draw attention to racial inequity in the school system.

Hagopian credits the Social Equality Educators, a group of social justice-minded Seattle public school teachers of which Hagopian is a member, for bringing the racial-equity lens to the union’s organizing efforts. He calls the ideology and strategy behind this string of recent actions “social-justice unionism.” “The state legislature has shown over and over again that they don’t care that families and students and educators want our schools fully funded,” Hagopian says. “It takes collective action and the power of labor to go on strike to challenge the powerful—the one percent that are benefiting from this oppression and from our [regressive] tax code.”

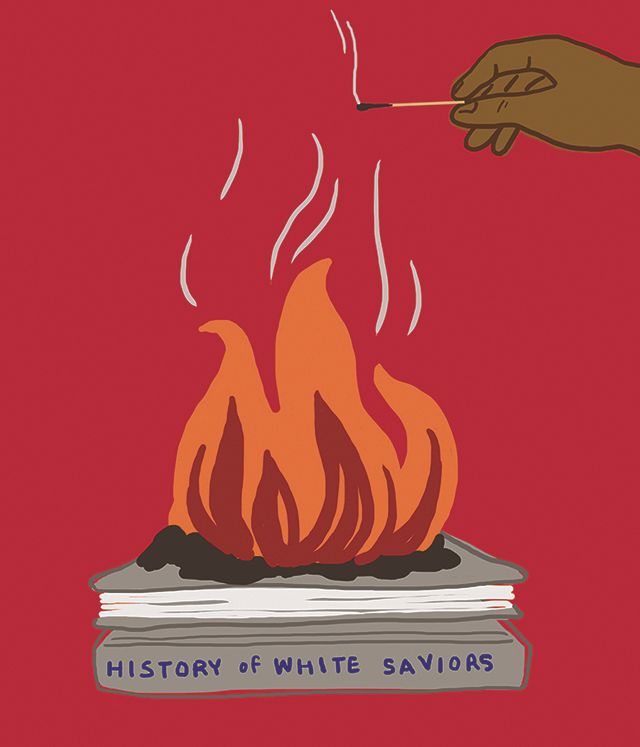

Now, Hagopian, the Social Equality Educators, and the Seattle and King County NAACP are pressuring the Seattle school board to implement an ethnic-studies curriculum across the district. The proposal, authored by the NAACP, is to integrate nonwhite perspectives and cultures into all existing classes in Seattle schools to combat white-centric curriculums, and, ultimately, close the achievement and opportunity gaps between students of color and their white peers. Recent research indicates that ethnic-studies curricula improve attendance and academic performance for students of color. The school board is dragging its feet, saying that they lack the funding. But Hagopian says the community will keep applying pressure, buoyed by the recent Seattle teachers’ union vote to endorse the NAACP resolution. “If the school district believes that [equity] is a priority, then they will honor that by supporting a curriculum that supports all the students,” Hagopian says.

Recent precedents set by victorious indigenous organizers fighting for historical acknowledgement should give Hagopian hope for the measure. In the fall of 2014, at the urging of Native American activists, the Seattle City Council established Indigenous People’s Day to replace Columbus Day, acknowledging the genocide that Columbus perpetrated against Native peoples. The motion was drafted by indigenous activist Matt Remle and sponsored by Councilmember Kshama Sawant. Then, in the spring of 2015, the Washington state legislature passed a bill mandating that all public schools teach a tribal-studies curriculum. Rather than beginning American history with European-settler colonialism, the “Since Time Immemorial” curriculum teaches students pre-contact indigenous history and follows the thread of indigenous American affairs through to the present day. Later that fall, the City Council approved another resolution acknowledging the traumatic practice of coercing American Indian students into boarding schools and calling for a federal reconciliation initiative, another Remle/Sawant motion. All these victories involved considerable Native American organizing effort.

For Hagopian, this kind of education activism not only serves to correct the historical record and diversify school curricula, but also to develop the next generation of activists. “We have a lot of problems in this world,” Hagopian says. “When students understand more about their history, they feel empowered to make change.” JOSH KELETY

news@seattleweekly.com