On February 18, Hillman City resident Charlotte Thistle was eating dinner in the front room with her four-year-old daughter, Ella, when a sudden hail of bullets slammed into their house, seemingly from all directions. Terrified, she grabbed her daughter and dashed into the back bedroom, cowering to the sound of glass breaking and bullets ricocheting from one side of the house to the other—BAM BAM BAM! When it finally stopped, she found dozens of bullet holes ripped into wood and drywall and two front windows.

Needless to say, it left her shaken. “I was pretty freaked out,” she says. While she’s used to hearing gunfire near her home, which is not far from the intersection of South Graham Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Way South, this was the first time her house had actually been struck.

“I started talking to people about it; we did get some news coverage, and there was a lot of chatter on Facebook,” she says.

Most of that chatter, she says, was about violence prevention. It’s one thing to talk about increasing police presence or gunfire surveillance technology (though as Seattle Weekly editorialized recently, such technology is controversial from a racial equity perspective and may not see results from a crime-reduction one), but many Seattleites are just as interested in figuring out how to stop people from shooting each other in the first place.

A friend on Facebook told her about Cure Violence (formerly CeaseFire), a Chicago-based program with community sites across the country and the world, founded in 2000 by Gary Slutkin, a physician and former head of the World Health Organization’s Intervention Development Unit. Cure Violence approaches urban gang and gun violence as a public health issue—violence as a contagion, essentially, a toxic epidemic that spreads from person to person, generation to generation. It can be tackled, Slutkin believes, in the same way a disease outbreak can be: by interrupting the trend, identifying and treating people most at risk, and ultimately changing the societal norms that gave rise to the epidemic in the first place. The only people Cure Violence believes can successfully interrupt the trend, though, are those who intimately understand and have credibility in a given neighborhood.

“The epidemic is reversed from within,” says Brent Decker, chief program officer at Cure Violence. “It’s not outsiders coming in. Not like a social worker or a teacher who hears about stuff three days later. … [It’s] someone with an ear to the street.”

The Cure Violence philosophy isn’t dissimilar to that of the United Hood movement, launched in Seattle last summer by ex-gang members and activists Amir Islam and Dwayne Malsted, whose aim was to get ex-gangsters like them to help stop gang wars, build alternatives to gun violence, and to intervene when — and before — shots are fired. Last fall, United Hood founders started preliminary work on what they called the “10 Summers Initiative,” which would, in part, develop a ground team to “help deescalate, mediate, and mentor gang-involved youth as well as those most at risk to violence.”

Cure Violence is also not unlike the informal work 180 Program co-director Dominique Wheeler-Davis has begun to do in Seattle. The 180 Program, funded by the King County Prosecutor’s Office, helps keep kids with misdemeanors out of the criminal justice system, but now Wheeler-Davis is trying prevent gun violence, too: When there’s a shooting, he and his guys try to figure out what’s going on, what led to it, and convince the people involved that there are better ways to resolve conflicts than with guns.

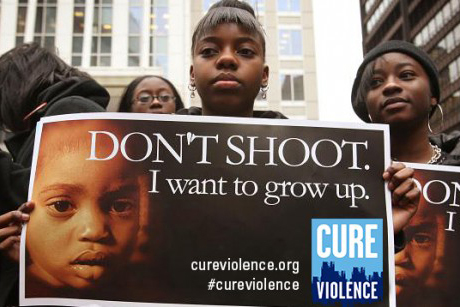

In Seattle and elsewhere in the country, street violence exacts a disproportionate toll on young black men. According to figures released by the mayor’s office at the beginning of June, of the 69 people who had been assaulted by someone with a firearm so far in 2016, “more than half of all victims are under the age of 30 and are African American.”

Thistle says she’s well aware that she, “a middle-aged white lady” who bought a house in the neighborhood six years ago, is not going to be able to solve the problem herself. “People who go and do the outreach work” as part of a program like Cure Violence “are gonna have to be people of color. It has to come from within the community. That does make it a little awkward, me trying to get the ball rolling.” Still, she’s bound and determined to support any effort that emulates the Cure Violence approach, and, hopefully, to use Cure Violence’s success rates and international clout to bring local efforts to scale (she’s in conversations right now with Wheeler-Davis).

“I really liked the sound of what [Cure Violence programs] do,” she says. “I come from a philosophy of nonviolence; it appealed to me on that level. And I have an interest in health care” (she’s studying nursing), so the public-health approach appealed to her as well. The Cure Violence model has been implemented all over the world–from Chicago to San Antonio to South Africa to Iraq–and its results have been studied extensively. In 23 of its U.S. sites, it has been shown to reduce the rate of shootings and killings by up to 73 percent. At Chicago sites, it’s 75 percent. Three sites in Baltimore have gone more than 365 days without a homicide; same with a site in Brooklyn. And although violence overall is up in Chicago and Baltimore right now, in the roughly 5-by-15-block areas with “Violence Interrupters” working on a person-to-person level, shootings and homicides tend to plummet. That’s part of why Cure Violence programs around the country have a good shot at snagging federal funding.

Thistle reached out to Decker, who told her that the typical budget to start a Cure Violence program in a new location is $500,000—largely due to the costs of paying for Cure Violence staff time as well as local staff time. It’s a big price tag, but one that’s dwarfed by the $5.8 million spent on the Seattle Youth Violence Prevention Initiative each year. SYVPI has made big strides since its creation in 2009, but maybe not quite as big as the city had hoped; it recently received a less-than-rave review from the City Auditor’s office. (The program is “limited in scope” and its current approach “lacks overarching strategic vision,” the report reads.) Half a million is also a whole hell of a lot less, Thistle notes, than the $160 million the city is proposing to spend on the Seattle Police Department’s new north precinct. “If it only costs that much and it works that well,” she reasons, “There’s no excuse for not trying it.”

Implementing a Cure Violence program would need community buy-in, though. Cure Violence does send a staffer for free to interested communities to give talks and trainings, but wouldn’t do so until there are enough people interested in it.

And that interest certainly isn’t there quite yet. Thistle reached out to at least half a dozen South Seattle communty groups and organizations and thus far has gotten the public support of the South Seattle Crime Prevention Council. Thistle and SSCPC president Pat Murakami co-hosted a screening last week at the Southeast Seattle Senior Center of “The Interrupters,” a documentary that chronicles some of Cure Violence’s local staffers, all former gang members or convicts or both, as they walk into intense situations in violent communities and bare their hearts, both pleading with and commanding everyone to stop the killings. In one scene, staffer Ameena Matthews pulls an 11 or 12-year-old boy in front of a crowd of young men at a vigil for another slain friend. “Who does this baby belong to?” she demands, her voice raw and piercing. “He sees everything y’all do. If he catch a hundred years [in prison], whose fault is it? Is it his fault?”

About 10 people showed up to the screening.

Still, it’s safe to say that all 10 were very interested in finding something – anything – that could actually curb the waves of violence before they start.

“I’m here because I’m looking for a solution; I want to know what I can do to be part of the solution,” says Bessie Gratton, who’s lived in Rainier Beach for the past 40 years. “And I want to support the people who are already working on solutions.” Rainier Beach wasn’t always violent, she says. “It was peaceful.” Now, “I hear gunshots around my house all the time,” and it’s horrific “to see the young babies kill each other for no reason.”

Toni Hall, who lives in Skyway, but spends a lot of time in Rainier Beach, says that she has many close friends who have lost family members to gun violence. “Horrible stories… The hopelessness of folks, you know? What are we gonna give our kids to look forward to? It would help a lot if they had summer jobs, or something to do. Not all of them, but some of them. That’s what brought me here. I’m interested in seeing what I can do to help. I think if everybody does a little bit, we can get a lot done.”

While Seattle certainly doesn’t stand out as a gun-violence hotspot (we’re not New Orleans, Detroit, Chicago, or Baltimore), still, the numbers have been going up in recent years — especially in certain neighborhoods, especially in South Seattle. As of early June, 144 gunfire incidents have been reported to police, 24 people have been injured, and five killed.

“No, we’re not a Chicago, we’re not a Baltimore,” conceded Murakami to the small group gathered on Wednesday.

But Hall chimed in immediately, to a soft chorus of affirmations: “We don’t want to get there, either.”

This story was modified on June 22 to add more context to the issue of gun violence as it pertains to young African-American men in Seattle. We apologize for any indication that these men alone are responsible for the violence.