Necessity is the mother of invention. And no one better demonstrates the truth of that aphorism than the desperate meth cook.

Washington’s pharmacies are about to adopt a new system, already popular in other states, aimed at curbing methamphetamine production. The program—uncreatively dubbed “meth check”—tracks purchases of pseudoephedrine, a drug that makes the sniffles more bearable when found in products like Sudafed, but which also happens to be a key ingredient in homemade meth.

Starting October 15, when a tweaker walks into Walgreens and tries to buy a packet of cold medicine, he will—in theory—be rebuffed by the clerk and tipped off to local law enforcement. The key words, however, are “in theory.” Because in other states that have adopted identical electronic tracking systems, the enterprising crank cooks have already devised ways to get their hands on all the pills they need.

Meth check is the result of a law passed last year in Olympia that limits customers to 3.6 grams of potentially misused cold medicines per day (about one or two packets), and no more than 9 grams over 30 days.

To enforce the new policy, the state’s Board of Pharmacy was ordered to adopt a real-time electronic sales-tracking system that alerts store clerks—and local police—to customers who have already bought suspicious amounts at other locations. This system is already in place in 20 other states, mostly in the south and Midwest, including Missouri, where I spent the last three-and-a-half years working as a reporter.

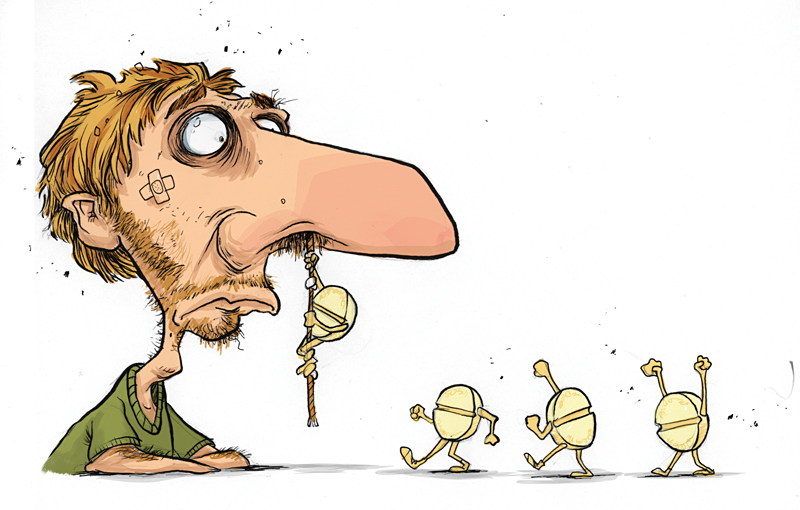

No place in America has a greater need for meth check than the Show Me State, which has led the nation in busts 10 years running. Its electronic tracking system went live on January 1, but the news thus far hasn’t been good: Authorities say that while it has made life a little more difficult for pill-gatherers, they’ve already adapted. “People are, instead of going to five different stores, just bringing four other people and each person makes a purchase,” a sheriff’s deputy told the Associated Press earlier this year.

The other gaping flaw in the electronic tracking system is that many meth cooks have changed their recipe, and the new formula, dubbed “shake and bake,” requires significantly fewer pills. The simple yet highly combustible process can be completed with just one or two packets of cold medicine—meaning that, to the objective gaze of meth check, a dealer with a picket-fence grin looks no different from a coed with a cold.

What’s more, several states that have had meth check in place for years have actually seen meth-lab incidents increase over time. The AP analyzed nine years’ worth of DEA data on meth-lab incidents, and found that electronic tracking “not only failed to curb the meth trade, which is growing again after a brief decline, it also created a vast and highly lucrative market for profiteers to buy over-the-counter pills and sell them to meth producers at a huge markup.” (Fans of A&E’s Breaking Bad recognize these profiteers by a different name: smurfers.) Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Kentucky have had electronic tracking systems identical to Washington’s in place since 2008, and since then meth incidents in those states have risen 164, 34, and 65 percent respectively.

So why are so many states still employing this ineffective policy? For one thing, it’s cheap. A spokeswoman for the Washington Department of Health says the state has spent only $23,000 in staff time getting employees used to the system, which is otherwise funded almost entirely by the same pharmaceutical companies that turn a handsome profit on continued drug sales.

That’s the other reason meth check remains popular. Despite evidence to the contrary, those companies claim electronic tracking is the best way to keep their product out of the hands of addicts, yet still easily available for people suffering from a runny nose.

“The makers of these medicines are in the business of making people who feel bad feel better,” Elizabeth Funderburk, spokeswoman for the Consumer Healthcare Products Association, told me last year. “They don’t want their medicine turned into methamphetamine.”

Testifying before Congress last April, Kent Shaw, the assistant chief of California’s Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement, disagreed. “The [pharmaceutical] industry has mastered appearing as if it is attempting to solve the problem,” he said. “In reality, it is merely perpetuating the problem in order to continue reaping the financial gains generated by meth labs.”

Shaw and other law-enforcement officials argue that requiring a doctor’s prescription to obtain pseudoephedrine—a policy that was in place in the U.S. until 1976—is the only surefire solution.

Results in Oregon seem to back this up. Before becoming the first state to adopt a pseudoephedrine prescription measure in 2006 (Mississippi became the second last year), Washington’s neighbor to the south seized more than 200 meth labs annually. Two years ago, police there found just 10.

This year, Missouri’s governor and attorney general are lobbying for a prescription-only model for pseudoephedrine. The proposal has drawn fierce opposition from the pharmaceutical lobby, and also from citizens concerned that cold medicine won’t be readily available when they really need it. This argument fails to consider one important point: Sudafed ain’t the only game in town. So the next time you’re feeling under the weather, remember the dozen or so brands of over-the-counter cold pills that don’t contain pseudoephedrine.