When the nationwide hysteria over people dressed as creepy clowns reached Washington state earlier this month, just in time for Halloween, clowns at Room Circus got scared—but not the way the rest of us did. These are professionals trained in the art of medical clowning, an art that began in New York in 1986 and has been increasingly recognized for its medical value in reducing stress, pain, and fear in hospital patients. Every Friday, the clowns at Room Circus visit Seattle Children’s Hospital to entertain, distract, and generally make the kids feel better. However, with clowns suddenly becoming objects of terror rather than joy, Room Circus sent out a press release last week saying that their efforts to raise money have become akin to “raising money for ax murderers.” Whoa.

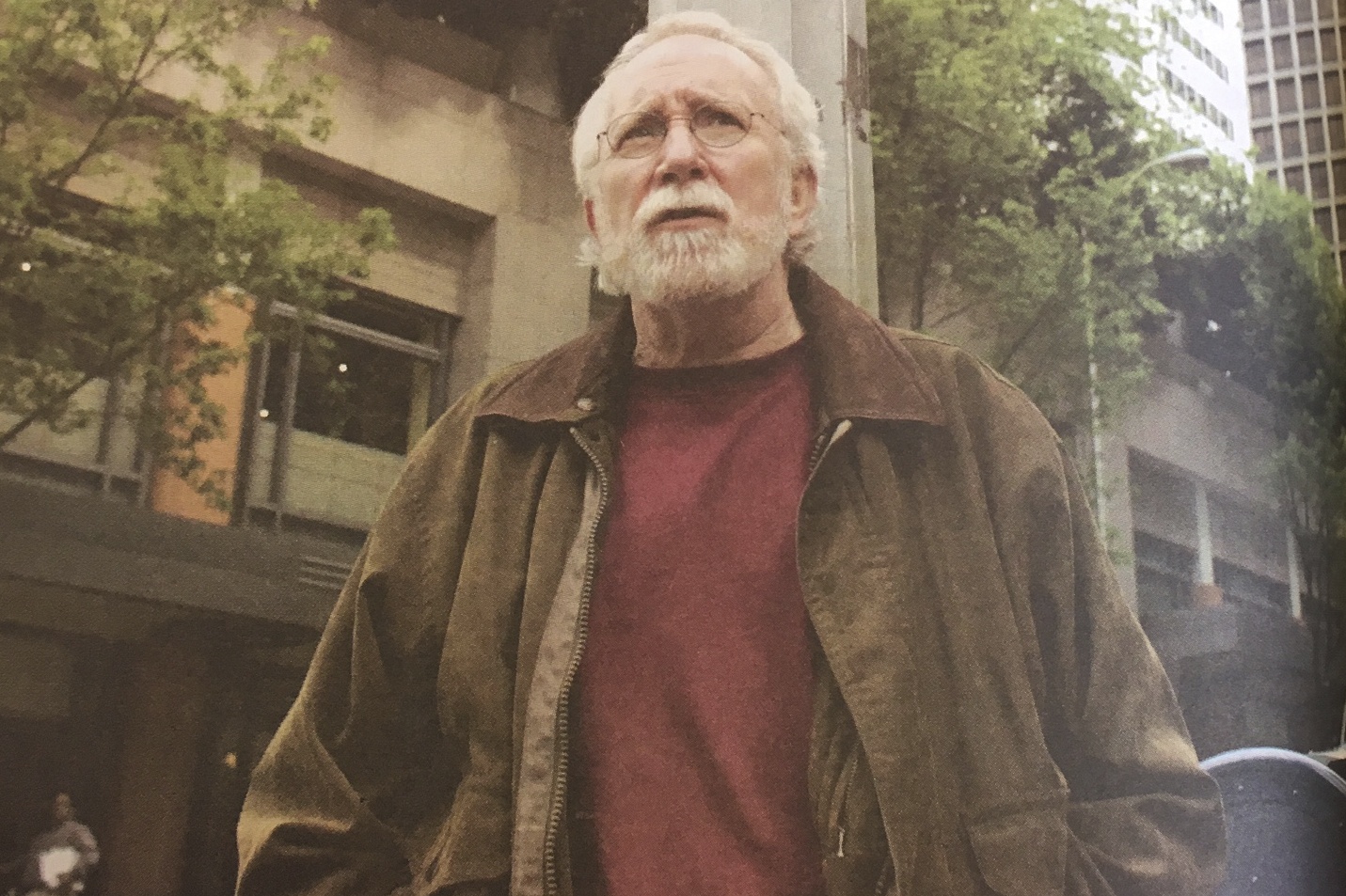

Linda Severt is program director and head clown of Room Circus. She talked with Seattle Weekly about how medical clowning works, and her worries that the creepy clown freakout could scare donors away from Room Circus and take the fun out of clowning for everyone.

What goes into the art of medical clowning? The skill, basically, is having a high degree of sensitivity and compassion. We play clown doctors, so we all have doctor names—my doctor name is Doctor Hamsterfuzz—and we wear altered doctor jackets. Our makeup is very toned-down—when people think of a sort of traditional clown, they think of more the full-face paint or something looking like a mask. We don’t do that. We do a lot of medical parody, just sort of turning things upside down, parodying the various equipment that’s used in the hospital, pretending to be doctors. And of course we’re completely incompetent, and we need a lot of advice from the patients, who are empowered through this process.

How do the clowns decide what approach to take with each patient? We all have a variety of skills, from music to magic to juggling to physical comedy, but the biggest, most important skill of all, and the most difficult and challenging one, which is at the core of clowning, is improvisation. We take in everything that’s going on in the room, the condition of the child, the equipment that’s there, the staff and family, and make something up, basically. We have skills to draw from, and we can incorporate those skills into whatever routine we come up with.

If the child is extremely sick, we’ll have a more toned-down approach. If there’s any fear that we detect, we just stay in the doorway, and we never come in the room without the child’s permission. We can do a soft lullaby—we stop babies from crying all the time, it’s beautiful, it’s really sweet. We can appeal to any age and any situation. If a child is extremely active, we can go in with that same level of activity—we can match that energy, and then the child looks up puzzled like “Wait, what?”

How do you deal with working in the hospital environment, which can be an upsetting place? It’s very challenging sometimes, especially now that we’re working with kids in the cancer ward, intensive care. We get attached to them, and even the ones we’re not attached to, we do see a lot of difficult and challenging stuff. What we do is we play to the child. There’s a sick physical body, but there’s still a child within that body. We bring out the child. If we dwell on all the sadness and pain, that would be pretty overwhelming, but basically what we’re bringing is joy to these situations, and that is so deeply rewarding and gratifying that it sort of helps deal with the rest of it.

Why clowns—is it just traditional, or is it also an intentional choice? I think the clown lends itself to this work as opposed to an actor or a comedian because clowning is about parody, it’s about reflecting society back and being able to laugh about it. A comedian, for example, they just stand up and deliver the funny and the audience responds with laughter. What a clown does is involves the audience, involves the patient in the routine or in the laughter. Every room that we go into we turn into a circus, if you will. The child is ringmaster and they can tell us what to do.

Do you think there will actually be a drop in funding because of the creepy clown scare, or is it just a worry at this point? Well, fundraising is a challenging period, and we’ve got a strong program. We haven’t felt the results of it yet, but I’m a little worried about it because it has sort of taken the nation by storm. In this media-crazed day and age, things get spread and things get blown out of proportion. You know, these people wearing the creepy masks are trying to get attention, but basically they’re just bullies wearing masks, they’re not clowns at all.

Has the general fear of clowns been a problem even before this latest scare? I mean the fear of clowns has been around for quite a while—it’s already a problem. So now it’s even worse. Thanks a lot, Stephen King! I think that some people are afraid of clowns even apart from the scary-clown thing. My theory is that it may be because there’s no culture or history of masks in our culture. People are unfamiliar with that, and so when they see a mask, whether it’s a mask sort of like clown paint, it’s unfamiliar and therefore lends itself to be a little bit scary. And then the thing that’s affected us the most is definitely all the scary clown movies, starting with It, which I’m sad to hear is being remade. So this problem could become worse before it gets better. I hope not, I hope that we’re educating the public, I hope that that really sinks in and makes a difference.

crobinson@seattleweekly.com

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.