Last Friday morning, Jan. 2, most Eastern Washington cattle ranchers were worrying less about the snow blanketing their spreads than the latest bad news about live-beef prices from the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Not Joel Huesby. His one concern that morning was whether the snow would prevent his getting to the title office in nearby Walla Walla in time to sign a 30-year lease for another 175 acres of pasturelandto raise more beef cattle.

Huesby is a new breed, or rather an old breed, who has learned to cope with the challenges of the 21st century. Ten years ago, he and his family opted out of the system whereby America breeds, raises, sells, and slaughters its beef and dairy cattle. They joined a minuscule but growing number of producers operating outside the multinational machine that has driven down prices, driven independent ranchers, processors, and butchers out of business, put four-fifths of the nation’s protein supply under the control of just five corporations, and in the process exposed that protein supply to new and terrifying hazards like antibiotic-resistant E. coli outbreaks and mad cow disease. The Huesbys weren’t thinking about protecting the public from food-borne disease when they dropped out of the system back in 1994. They were just trying to save the farm that had been in the family for four generations, and they bet the farm to do it. Protecting public health was an incidental by-product of the kind of ranching they turned to, and after 10 tough years, it might turn out to be the key to their future expansion and success.

In 1994, Joel Huesby convinced his family to convert their farm into a pesticide-free ranch for supplement-free cattle.

(3hats.com) |

The Huesbys raise their cattle the old-fashioned way: on pasture during the eight to 10 months that pasturage is available, on silage and hay during the rest of the year. They don’t dose their animals with hormones or antibiotics to hasten their growth; they don’t feed them grain to fatten them; and they don’t lace their feed with protein supplements made from the offal, blood, and bone of less-lucky species-matesthereby eliminating any chance their animals might be exposed to the infectious agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE). Little is known for certain about BSE but one thing: Noncannibalistic cows don’t catch it.

The Thundering Hooves Family Farm in Walla Walla County.

(Thundering Hooves) |

The Huesbys don’t even fertilize the pastures their animals graze on; they leave the fertilizing to the animals they raise. “We believe in letting our cattle do as much of the work as possible,” says Joel, the family spokesperson and the guy whose vision led to a new way of cattle ranching and beef marketing under the Thundering Hooves Family Farm label.

PROFIT, THEN HEALTH

Before all this, Huesby recalls watching a field of wheat stubble burning, preparatory to plowing and replanting, and wondering how to keep his farm from bankruptcy. A few weeks earlier, he’d harvested a field of green beans and managed to sell them to a nearby cannery for around $100 a ton. Even with a good yield of 5 tons per acre, he was barely breaking even. “The canneries and the fuel man and the parts man and the fertilizer man and the aerial spraying man and even the migrant workers were all making a living from my land, but not me.”

From those dismal mental calculations while watching the black smoke swirl came a resolve to break a cycle embraced by four generations of Huesbys, of farming ever more intensively with ever more machinery and chemical fertilizers to produce ever higher yields to be sold to ever larger agribusiness conglomerates for ever shrinking margins. “So it was from that moment I resolved to do nothing the same again,” he says.

Keith and Clarice Swanson.

(Thundering Hooves) |

Huesby’s first challenge was to persuade his parents and siblings that his epiphany could be translated into dollars and cents, a literally down-to-earth business plan. First, get off the commodity-crop merry-go-round by ceasing to farm and starting to ranch, turning the farm’s 225 acres of tractor-compacted, topsoil- depleted, nutrient-starved farmland into pastureland, capable, once it recovered from almost a century of exploitation, of grazing three head of “stocker” cattle or two pair of cows with calves on natural grass forage.

ON A FIRST back-of-the-envelope calculation, raising beef cattle this way, with no concentrated feedlot finishing, is almost laughably inefficient. But with the passage of time, other benefits kick in. Herbicides and pesticides are expensive to buy and apply; no plowing means soil that’s more porous and requires less irrigation.

Such savings aren’t anything like enough to make organic pasture-raised beef competitive with feedlot beef in price. Fortunately, a lot of people are concerned about the appalling conditions under which commercial beef cattle are raised and killed, and they are willing to pay a premium to be assured the beef they eat was naturally nourished and humanely slaughtered.

Such people compose a minuscule and widely scattered portion of the national appetite for beef. Finding them and turning them into customers was the next challenge. Fortunately for the Huesby pocketbook, about the same time the farmers-market movement was spreading across the nation and the Northwest, providing a direct-sale opportunity for Thundering Hooves beef (and lamb and poultry) and entirely bypassing the layers of processors, shippers, brokers, and wholesalers whose share of each sale had driven ranchers into the red.

On the Huesby ranch, cattle graze on grass eight to 10 months of the year.

(Thundering Hooves) |

Thundering Hooves’ success is due in large part to keeping the business in the family. Father Gordon provides business acumen, mother Lois keeps the family books, Joel’s wife, Cynthia, runs retail marketing, brother Bryan is in charge of operations, sister Clarice and her journalism-teacher husband, Keith Swanson, look after the west-of-the-mountains market and PR.

But there’s no question that Joel was and remains the spark plug, a persuasive writer and mesmerizing lecturer who speaks with such passion about the superiority of Omega-6 fatty acids and mature soil biota that one feels almost called upon to mount up and join the cattle drive. And there are more people every year who have done so, people concerned with humane treatment of animals, people determined to reduce the level of chemical pesticide, antibiotic, and hormone residues in their foodsome, even, concerned with nothing but getting the best piece of beef possible for their table.

EVERYONE KNOWS that the best-tasting beef is grain-fed and heavily marbled with fat. Everyone but Joel Huesby. One of his favorite sales tools is the ground-beef challenge, pitting supermarket burger against his grass-fed patties. Though leaner than Brand X, he says, grass-fed beef retains more of its flavor-enhancing unsaturated fats when cooked unsaturated fats which, he claims, when consumed in moderation, are actually beneficial to health.

Yes. Cook our ground beef on your stove next to the best ground beef you can find in your local grocery store. You should see and taste the difference! Skilled hunters know that calm animals taste a whole lot better than stressed-out, adrenaline-filled game. We dry-age our beef for a minimum of two weeks, which breaks down the muscle fibers and brings out added flavor and tenderness. We strive to bring you appropriately finished beef. We do not sell extra-lean beef. Fat is flavor, and the right kinds of fats are actually good for you.

HERESY, HERESY ON THE RANGE

This once-heretical assertion is garnering more support every year. The latest evidence is deployed in a just-published book, Pasture Perfect, by Jo Robinson, the first author to widely disseminate information about the health effects of grass-fed ruminants in her book The Omega Diet. (It was another Robinson book, Why Grass Fed Is Best, that inspired Joel Huesby to take the pasturage route with his cattle and poultry.)

Unlike many evangelists for organicity, Robinson backs up her passionate beliefs with thorough research, combing through scientific journals for leads on the latest experimental results in the nutrition field. Growing up in a family devoted to the dicta of 1970s healthy-eating guru Adele Davis, Robinson had an epiphany of her own in a New York cancer lab, where she encountered evidence that a diet high in corn oil”corn oil, which we’d all been told was so good for us!”caused a fourfold increase in the rate of tumor growth in rats.

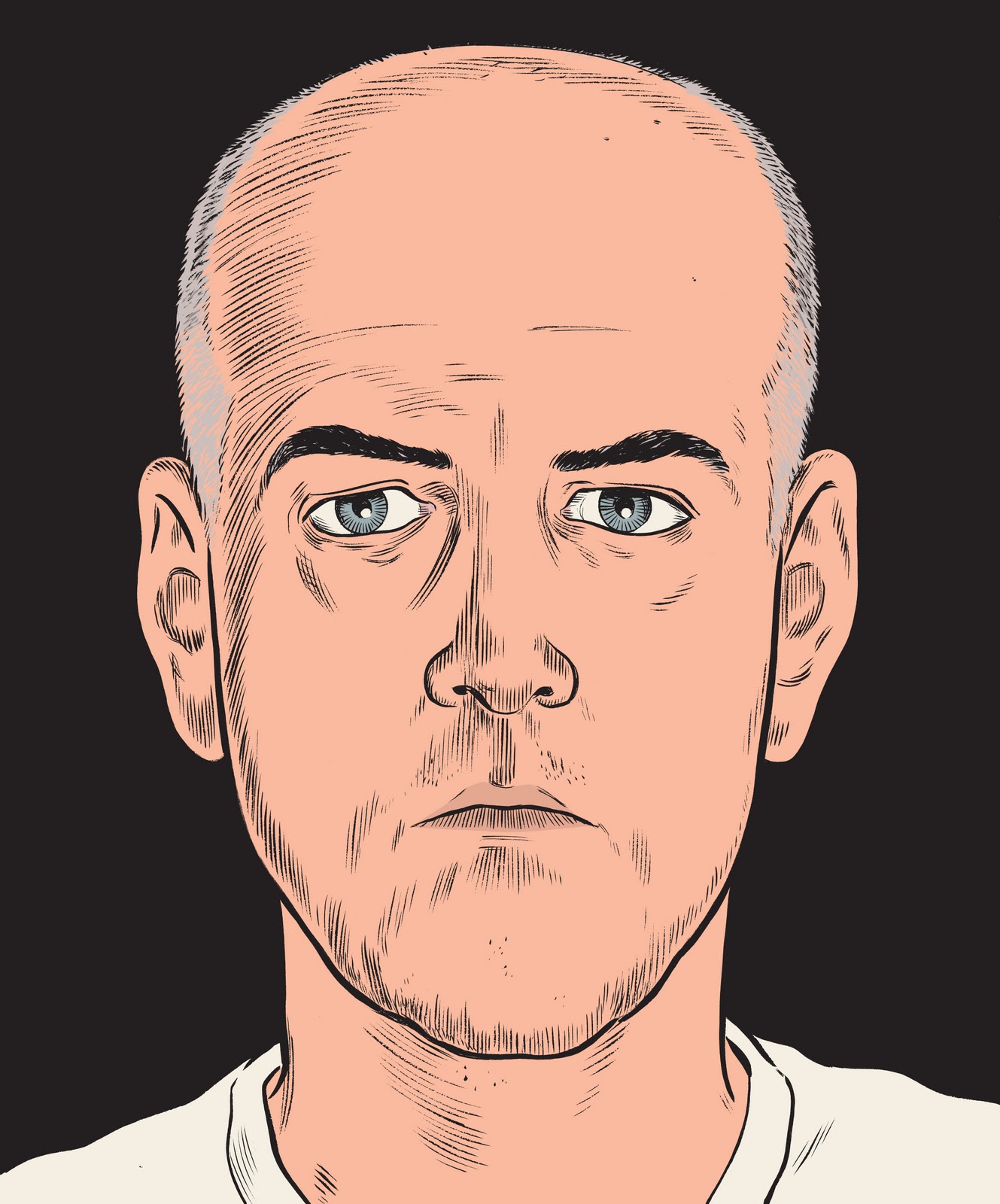

Jo Robinson, author of The Omega Diet. |

After publishing The Omega Diet in 1999, the Vashon Island-based Robinson became a kind of high priestess for the pasture-feeding movement. But a letter from some Texas bison ranchers, setting her straight about a misstatement, taught her she still had more to learn. “I had said that bison were high in healthy fats because they were range-fed, and they told me that, unfortunately, most bison in America are grain-fattened in feedlots. They invited me to their ranch, and I learned from them what a totally holistic operation is like and how totally different from industrial practices.”

While a long way from industrial-strength, Thundering Hooves is a relatively big operation. A survey of entries on Robinson’s Eat Wild Web site index of earth-friendly ranchers nationwide shows that typical operators are smaller but are sprouting in friendly pockets and crannies everywhere. Washington state appears to offer particularly nourishing niches, with more than 20 farms and ranches listed. FAIRLY TYPICAL of Western Washington ranchers are people like George and Eiko Vojkovich, who often attend the same farmers markets as the Huesbys, selling poultry, eggs, and beef. The Vojkovichs’ Skagit River Ranch near Sedro-Woolley is pretty much staffed entirely by George and Eiko, though 9-year-old daughter Nicole takes care of feeding the two goats. The Vojkovichs run about 200 head of certified red and black Angus on their 260 acres, with 600 laying hens and a seasonal flock of 2,500 broiler hens comprising the major poultry component.

George’s dad farmed in the winter and fished in the summer. Farming looked like too much work, so after high school young George spent 20 years as a commercial fisherman before deciding he was sick of the lonely life at sea. Settling in Westport in Grays Harbor County, he worked building factory trawlers for Alaska Fisheries and started an oyster farm on the side, discovering that his knees wouldn’t take slogging through the mud. By that time he met Eiko, who was vice president of international marketing for Alaska Pacific, and the two decided in the mid-1980s to relocate to the Skagit. “I was a total redneck, junk-food junkie back then,” says George, “I thought organic food belonged with ponytails and patchouli oil. But I had a heart attack, and three days in the hospital got me scared. There was a doctor up here who ran a country clinic and taught healthy eating, and I settled down to do my homeworkand lo and behold, I learned that a healthy diet for me started with healthy soil on the farm so that healthy microorganisms could grow. I remembered how my grandfather, who was also a fisherman, would bring back fish heads to fertilize the garden, and how I used to turn the compost for him. So here am I, who totally bought in to the faster, more, bigger, better kind of agriculture, come around full circle to where my grandfather was, learning that if the soil is sick, the grass and the animals who eat it can’t be well, or the people who eat the animals. We are what we eat. We sell what we eat ourselves. It’s as simple as that.”

RANCHERS LIKE the Vojkovichs already had a string of faithful customers when the first U.S. case of BSE was diagnosed just before Christmas. It’s likely that demand will nicely outstrip supply in the future. The Huesbys are certainly hoping so. In addition to the land leased from the Puget Consumers Co-op Farmland Fund, which specializes in acquiring land threatened by development, the family has just purchased the Quik Freez packing facility in Walla Walla and will soon have a U.S. Department of Agriculture processing license allowing them to ship their products interstate. Also in the works is a mobile slaughter facility that can be moved right into the pasture where a targeted animal is browsing, thereby minimizing the stress before slaughter and the waste accumulation after.

From left, George, Nicole, and Eiko Vojkovich. |

With 175 new acres next door to its present 225, the Huesby property south of Lowden in Walla Walla County has the potential to produce more than 1,200 head per growing seasonfar more than the market can absorb (though fear of mad cow might accelerate the trend to grass-fed beef). But the family is not putting all its resources into beef. The ranch already produces lamb and chicken, as well, about a third of which is shipped to high-end restaurants. Another third goes to direct sales in the Walla Walla area (a retail storefront is planned for the Quik Freez facility), and a final third is sent to Seattle-area farmers markets.

In 2003, Thundering Hooves experimented with raising heirloom turkeys free-range style, using starter stock from a hatchery in New Mexico. The experiment was so successful that when the Huesbys learned that an heirloom turkey grower in central Oregon was looking to get out of the business, they purchased breeding stock and equipment from him and are setting up to build their own flock, carrying on a unique strain of turkey that was considered close to commercial extinction only three years ago.

THE RISE OF RANCHES like Thundering Hooves is bad news only for people who believe that eating animals, no matter how humanely raised and killed, is simply wrong. There’s no way to argue with this viewpoint: Humans can be healthy and avoid food-borne disease without ever laying lip to animal protein. But surely there’s something to be said for operations that try to minimize the cruelty and discomfort that pervade the industrial meat-protein system, which reduces living things to raw material, as undifferentiated as toothpaste or talcum. Perhaps Bill Nyman, a pioneer of organic pastured cattle raising, puts it best when asked, as invariably he is, about being in the business of killing fellow creatures for profit. “They only have one bad day,” he says mildly. “How many of us can claim the same?”