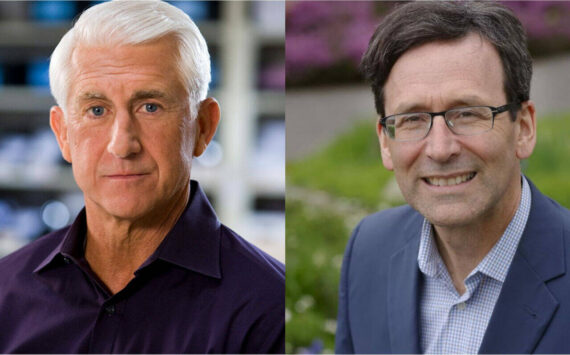

Carbon Washington, a revenue-neutral carbon-tax proposal, launched its campaign last year and collected more than enough signatures to become an initiative to the legislature in this one. But nothing much happened in Olympia. It got punted to the November ballot, and is now officially in voters’ hands. As a result, I-732 supporters—who now include venerated climate scientists James Hansen and Richard Gammon—are upping their ground game … again.

“We always believed this was going to the people,” says Carbon Washington executive committee member Ramez Naam. “We always believed Olympia was a longshot because of the split government and because of the short session. That said, Olympia was remarkably more constructive than we’d thought. We had members of the legislature on both sides of the aisle taking seriously the idea of a carbon tax.”

For Naam and Carbon Washington, the message now is both simple and urgent: “What are we waiting for?” Climate change is upon us. The direst predictions have already begun to unfold. Putting a price on carbon has worked in British Columbia, supporters say, and by using carbon-price revenues to cut sales tax and fund Washington’s Working Families Tax Rebate, I-732 would make the state’s tax code—easily the nation’s most regressive—look a lot better to low-income residents for the first time in decades. 2016 is the year to strike, says Naam, because presidential elections always get big turnout, especially among younger, more progressive voters.

“We’re not in this just to win in Washington,” he adds. I-732 is the first ballot measure of its kind in the nation. “What we really want is to send the message that citizens in all 50 states can take serious action on climate.”

However, the deep ideological rift in Washington’s environmental movement remains. Last Friday, on Earth Day, the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy—a coalition of environmental, labor, and community groups that has long opposed a revenue-neutral carbon tax, promising to draft its own, revenue-positive initiative—released its most detailed proposal yet for an alternative climate ballot measure. The proposal puts a price on carbon, too, but also calls for a carbon-emissions cap, and uses the taxes generated to invest in renewable energy, clean water, healthy forests, low-income communities, and in transitioning workers and businesses off of fossil fuels. Alliance members will bring the proposal on a listening tour across the state this summer.

But despite earlier promises to the contrary, there will be no ballot initiative this year. “It seems very unlikely it would be successful” given the competition with I-732, says Becky Kelley, president of the Washington Environmental Council, a key partner in the Alliance, which recently outlined on its website its reasoning for opposing I-732. (Among the arguments: I-732 relies “solely on economic signals” to drive down carbon emissions.) The Alliance’s proposal is still likely to be a ballot initiative, says Kelley—just not in 2016.

While the rift here may seem arcane, “it’s not just a geeky or wonky preference for one policy over another,” she says. It’s based on “a whole theory of change about what it’s going to take to address climate change effectively and equitably over time.” Taking carbon-tax money and putting it toward renewable energy, healthy forests, and better access to public transit, for instance—that kind of approach is designed not just to reduce but to accelerate the reduction of carbon emissions.

“I think we have every bit as good of an urgency argument as I-732,” she says. The idea is that when the Alliance’s proposal kicks in, “it’s going to be having a significant impact [on carbon emissions] right in the beginning.”

Plus, this kind of colossal systemic overhaul “is not a short game.” The Alliance’s theory of change requires doing the painstaking work of bringing together as many people as possible not only to discuss but craft the policy.

“It has been hard, and it has been slow,” she concedes with a laugh. But “we believe it will be better policy.”

Still, to many economists, activists, and climate scientists, supporting I-732 only makes sense. To some, it’s a moral call to arms; to others, it’s “Love the One You’re With.”

“I don’t think we can have any progress in protecting the climate or reducing emissions without a price on carbon,” says Gammon, emeritus professor of chemistry at the University of Washington and a climate-science heavyweight who’s been monitoring carbon-dioxide emissions in the atmosphere since the 1980s. I-732 “is what’s before us,” he says. “I have to support that. It doesn’t mean it’s perfect, or that we can’t have future revenue-positive initiatives. I don’t see it as either/or.”

Adds Naam: “You don’t go to [the ballot in] November with an initiative you dreamed of. You go with the initiative you got 330,000 signatures for. It is utter insanity for anyone who claims to care about climate change and claims to care about making a more progressive transition [off of fossil fuels] in Washington to not be full-throatedly supporting I-732. And if you want to amend it later, hallelujah.”

In Naam’s view, the precedent that the nation’s first carbon-tax ballot measure sets is alone cause to do it now. “It’s easier to come and tweak it later than it is to not get it done.”

But Kelley argues that this is also where the two efforts’ theories of change diverge; too often, do-it-now-and-fix-it-later hasn’t gotten us lasting results. “That’s not the way to build a movement,” she says. “The transition to clean energy is a process; you don’t flip a switch on election night. It’s a pretty profound transformation we’re envisioning here.”