There are a few tough biker chicks in the small Henry gallery displaying Danny Lyon’s famous ’60s photos from The Bikeriders (through May 4), but they’re the outsiders in this macho enclave. They ride on the backs of choppers—almost never piloting their own bikes—and watch their boyfriends race, drink, and play pool. Lyon actually joined and rode with the Chicago Outlaw Motorcycle Club (this after documenting the Civil Rights movement in the South), and he has an easy familiarity with his subjects; sometimes he’ll even frame a woman alone—hair sprayed, leaning on a jukebox, idly smoking a cigarette, or holding a baby. Still, the atmosphere to these iconic scenes is all testosterone, gasoline, and grease. A guy’s world.

And so, usually is the art world: Men dominate. That’s why the Henry’s three larger ongoing shows are so welcome. The female artists represented here outnumber Lyon by a ratio of 4:1 (I’ll explain the math discrepancy below). Their work is disparate, not specifically feminist or concerned with gender, but there’s an aggregate force to this clustering. I can’t think of the last time I’ve been to a museum, if ever, when men were in the minority.

Upstairs, German artist Katinka Bock came to town in January to talk about A and I (through May 4), her first solo show in the U.S. My theory, though I forgot to ask her at the time, is that the A stands for architecture, since the 13 installations here deal mostly with materials, buildings, building sites, and architectural salvage items that show traces of prior use.

“It’s another life,” says Bock of some ground-up old sculptural ornamentation, now little more than sand, pressed under a sheet of glass (rather like a huge microscope slide). Time and history have worn down her source materials (some from the Henry’s own basement), including an old set of doors, a propane hearth, floor tiles, a rusty I-beam, and even a soccer ball—this strapped to a wall with zinc construction tape—that bears scuffs from its previous life on the pitch. One small gallery is filled with the excavated dirt from a Belltown building site. From the ceiling hangs my favorite piece, Patron, a pencil-on-cloth rubbing from an old Roman wall, suspended in a rectangular enclosure.

With most of her pieces new and commissioned by the Henry, Bock puts you in mind of Buster Simpson’s recent show at the Frye—so much of his work also using weathered and reclaimed materials, shaped by forces outside the artist’s studio.

This year’s winner of the biennial Brink Award is local Anne Fenton, who has five newly created works on view through June 15. Earlier this spring, during the installation, she told me the pieces dealt “with issues of labor and what it is to be an artist today. And also issues of time and duration.” Spinning linen and baby-alpaca wool into a small black basket of socks—all the same continuous material—certainly took a lot of time, as did her handmade cotton hammock and the small group of stencils made on linen she created from flax.

Fenton doesn’t draw, she explains, but she’s fond of setting up a video camera to record situations of her devising. In one 35-second video, she spins a favorite ceiling lamp like a disco ball. For Mystical Fire, lasting an hour, she bought the titular product at a New Age shop—“a light show for your fire,” she calls it. At dusk, she lit the thing in her outdoor barbecue and let the video camera run. “I had no idea what would happen,” she says. It initially fizzled and died; she went back in the house, then returned to find it burning green and crackling, with the microphone also picking up traces of the city, jets overhead, and chattering birds. It’s a bit like watching campfire embers, though the video would benefit from a larger projection size. Maybe it’s not mystical, but as in Bock’s work, there’s a recording of time and decay, a reordering of the history contained in found materials. (Fenton will lead a private, after-hours tour on Saturday; RSVP through the Henry’s website.)

You get two shows in one with Parallel Practices: Joan Jonas & Gina Pane, (through June 8), though the two artists actually occupy separate galleries. The traveling exhibit comes from Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, and it celebrates the American Jonas and the late Frenchwoman Pane, both born in the ’30s and coming of age artistically in the ’60s. These generational peers were much more up against the male art establishment than Bock (born in the ’70s) or Fenton (an ’80s baby), and both would more generally identify as feminist. Like those two heirs, neither Jonas nor Pane is a fine artist in the sense of drawing, painting, or sculpting. Rather, with video and other media, they document the labor and physical investment in creating performances or installations—most of them one-offs never to be repeated.

Pane, in her first substantial U.S. show, often subjected her body to ordeals of the flesh. In one photo is a row of rose thorns pressed into her bleeding forearm, her palm cut by a razor. We see sliced, bleeding skin in other documentary images, too. Mounted on the wall is a large metal ladder or grate, about 10 feet tall, which Pane fabricated in 1971 so that the climbing steps were studded with sharp—but not quite flesh-rending—spikes. She climbed the thing barefoot over and over to the point of exhaustion, as we see in a companion photo series that makes a diptych of Action Escalade non-anesthesiee (or Action Non-Anaesthetized Climb).

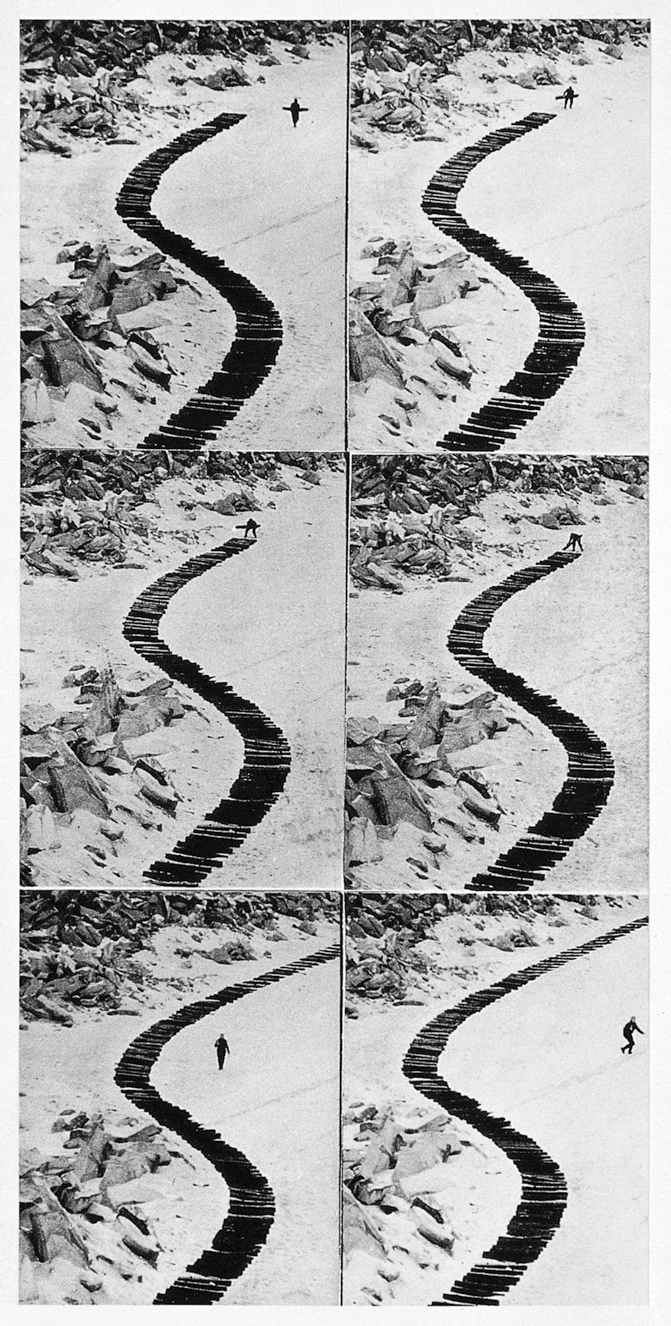

Why all these ordeals, this physical self-abuse? Body art is the usual shorthand for Pane. She’s sometimes cited as an influence on Marina Abramovic, who’s restaged some of Pane’s “actions,” which do suggest the early church saints and martyrs. (One work here makes explicit reference to the torments of St. Sebastian.) They suffered and died for Christ, renouncing the flesh to become pure spirit, but what’s the subject of Pane’s devotion? Here is a woman who made an object of her own body, rather than letting men do it for her. A lesbian who died in 1990, Pane had no use for men; she controlled and documented the terms of her suffering. None of it is pretty, but occasionally she ventured outside the studio to create something less hermetic. In the 1970 photo series Continuation d’un chemin de bois (Continuation of a Wooden Railroad ), there’s a suggestion of earth art as Pane laboriously lifts into place a series of railroad ties until they snake out of frame. There’s also the suggestion of escape, even if none of us can escape our own bodies.

Jonas’ work is considerably less forbidding. Her 1976 video Good Night Good Morning is like an 11-minute selfie, as she films herself during a year of daily greeting rituals. The more recent Reading Dante III comprises four separate videos (with benches so you can keep altering your viewpoint), custom lamps, documentary sketches, tree branches, and collage. It’s an immersive, somewhat whimsical installation full of dancers, singers, children, toys, horse-head masks, and anatomy lessons.

Her art is no less personal than Pane’s, equally rooted in process and performance, though it’s far more outward-looking and expansive. At 78, Jonas is still an active participant in the art world, and she was just selected to represent the U.S. at next year’s Venice Biennale—a rare honor for any working artist, rarer still for a woman.

bmiller@seattleweekly.com

HENRY ART GALLERY 4100 15th Ave. N.E. (UW campus), 543-2280, henryart.org. $6–$10. 11 a.m.–4 p.m. Wed., Sat., & Sun.; 11 a.m.–9 p.m. Thurs.–Fri.