One morning last spring, 9-year-old Tyler Stoken awoke in his modest rambler in Aberdeen, Grays Harbor County, and asked his mom to make him bacon. He was about to take the Washington Assessment of Student Learning, the statewide test better known as the WASL (“Wassle,”), and Tyler had been told at school to have a good breakfast. The test was important to Central Park Elementary, as it is to all schools. The WASL is the linchpin of a decade-old movement in Washington, mirroring efforts in other states and at the federal level, to reform education by raising standards. Newspapers publish the test results, underperforming schools are subject to potential federal sanctions under the No Child Left Behind Act, and, as Central Park Principal Olivia McCarthy later told an investigator for the local Educational Service District (ESD), educators “are under constant pressure to perform.”

Tyler wanted to be ready for this all-important test, and he had every reason to believe that he was. He was a bright boy who got great grades, scored in the 89th percentile on the national Iowa Test of Basic Skills, and was so favored by his third-grade teacher that she asked to have him back the following year.

“I think I aced it,” he told his mom after one day of the test, which spans two weeks. On a subsequent day, however, he faced an essay question that stumped him. It asked him to imagine that he saw his principal flying by the window and to write several paragraphs about what happened next. He sat there, not writing a word. “I didn’t want to make fun of the principal,” he explains, quietly recalling the episode while leaning against his mom.

At the time, Tyler didn’t say why he found the question so difficult. All his teacher, and later his principal, knew was that he wasn’t performing. And they did not like it. His mom, Amy Wolfe, says the school called her three times over the next couple of days, during which Tyler was repeatedly given the question to complete. The school wanted Wolfe to get her son to write that essay. The last time they called, he got on the phone, crying. Unable to figure out what was going on, Wolfe and the school finally gave up on the test. But Tyler hadn’t heard the end of it.

The Friday after the test was over, Central Park held a special event to celebrate the students’ hard work on the WASL. The kids had curled up in blankets from home as they watched Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events in the gym. Before the movie started, though, Tyler was called to the principal’s office. “She said I didn’t deserve to watch the movie,” Tyler says. She instructed Tyler to go to a table in the office’s reception area and put his head down. He was left like that for five hours and 20 minutes, according to a report by the ESD—so long that his neck hurt.

When he went home that day, Tyler had a note in his backpack from Principal McCarthy informing his mother that he would be suspended for five days because of his “refusal to work on the WASL.” The note called Tyler’s behavior “blatant defiance and insubordination” but made very clear that it was his score that caused such a grievous wound. McCarthy wrote: “As he chose NOT to perform, he will get a zero on that section, which will be averaged with the scores of all the other students in his class. . . . Additionally, this extends to the whole fourth grade, as our school score, the one that is reported to the state and the media, is an average of all fourth-grade students.”

The WASL has swept the state education system like a fever, an obsession, a madness. “Where can you go in the state of Washington and not hear ‘WASL’?” asks Washington Middle School teacher Debra Tarpley. In anticipation of the legislative session beginning in January, the Washington Education Association, the state teachers union, hired a pollster to conduct focus groups with teachers to find out what issues most concerned them. “They talked about the WASL,” says WEA President Charles Hasse. “He [the pollster] then asked, ‘What else?’ Then they talked about the WASL some more.”

“I dream about the WASL,” says Brittany Morris, a sophomore at Rainier Beach High School in Seattle. Tenth-graders there are expected to attend a weekly after-school WASL prep class, and there are “WASL Wednesdays,” when every class introduces some kind of practice for the test.

The pressure is greater than ever. This year’s sophomores will be the first class required to pass the reading, writing, and math sections of the 10th grade WASL before they can graduate from high school. Last year, just 42 percent of the state’s sophomores passed. At Rainier Beach, an overwhelmingly poor and minority school, just 7 percent passed. So the state faces the possibility that thousands of kids, perhaps virtually the entire senior class of some schools, will be left at graduation time in 2008 with no place to go. Even more kids will likely be in that position in 2010, when students will be required to pass the 10th-grade science WASL, as well.

The state will release this year’s results in June. “I’m thinking already about what I’m going to say to my constituents the morning the test scores come out,” one state legislator told Bellevue schools Superintendent Mike Riley, who declined to name the lawmaker. Legislators, who put the WASL in motion with a landmark education reform bill in 1993, have reason to fear a rebellion. This fall, in a survey the state teachers union conducted of its membership, 72 percent said they opposed having the WASL as a graduation requirement.

The WASL is designed in large part to hold teachers accountable, so it might seem natural that they chafe against the system. Even more striking, therefore, is the discontent among parents. The state Parent Teacher Association recently surveyed its 146,000 members about how they felt about the WASL. What came back was an outpouring of passionate testimony against the WASL, much of it relating personal experiences. From urban Seattle to wealthy Eastside suburbs to rural Eastern Washington, parents told disturbing tales about the way the WASL had become the be-all and end-all of their children’s schooling, producing crushing pressure and a narrowed curriculum. A representative comment from one Seattle mom: “I’m just angry about the whole thing and feel hostage to the system.”

In earlyOctober, the state PTA, not usually associated with radical positions, determined that it would lobby the Legislature to delay using the WASL as a graduation requirement and to seek “multiple measures of student achievement,” not just the one test.

“The Legislature is going to go full-bore on this,” says former Gov. Booth Gardner. He’s doing his best to make sure of it. Presiding over the state from 1985 to 1993, Gardner, a Democrat, got the education reform movement started. Over the past year, however, he says he has heard a constant din about the WASL that has convinced him that something has gone wrong with the effort to raise standards. Acknowledging the all-consuming pressure that the test has wrought, he says, “I don’t think anybody anticipated it.” Gardner looks at the alarming number of kids likely to end their senior year without a diploma and warns, “We’re headed for a train wreck.”

He says he spoke to Gov. Christine Gregoire about this and she said, in Gardner’s words, “Go fix it.” So Gardner assembled an ad hoc group of about 50 influential players in education, including the chairs of the legislative education committees, to work on a proposal to bring to Olympia in coming months.

Even some people who are presumed to favor staying the WASL course want a change in direction. Take Bellevue schools Superintendent Riley. One of the most admired superintendents in the state, he has led the charge to make college-level Advanced Placement classes part of every high-school student’s curriculum in his district. He is all about raising standards. Yet, he says, “You don’t take a week of kids’ time and make that determine whether or not they get a diploma.”

Riley also expresses disbelief that no system is ready to deal with the students who will be left in limbo once they fail. Students are allowed four retakes, and if they fail twice, they are supposed to undergo alternative assessments to demonstrate what they know. The state Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) is working on two pilot alternatives: One would require students to compile a “collection of evidence” of work, and another would allow them to use a high grade-point average to offset a substandard WASL score. The Legislature, however, hasn’t signed off on those alternatives. Nor has the Legislature or OSPI released remediation plans for those unable to achieve a diploma by any method. OSPI says it has developed five-week remedial teaching modules that it will unveil at a January conference, but those constitute short-term assistance designed for those who are close to passing, not those who need the most help.

“This is like Keystone Cops. That’s very high stakes,” Riley says, “and you don’t even know what’s going to happen next. . . . If I was a parent, I’d say, ‘Are you kidding me?'”

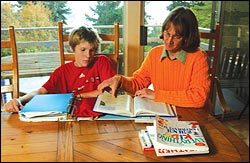

Mom Amy Wolfe and Tyler Stoken, 9, of Aberdeen: Failure to answer a question on the WASL was “blatant defiance and insubordination” and resulted in suspension. (Nina Shapiro) |

Molly O’Connor wants everybody to take a step back. “We got so caught up with WASL, WASL, WASL, we’ve kind of forgotten about why we’re doing this,” she says. O’Connor is a spokesperson for Partnership for Learning, a nonprofit supported by the state’s biggest companies, including Microsoft and Boeing. The group is the WASL’s biggest cheerleader aside from state officials. In the past few months, the partnership has mailed a series of glossy fliers to students’ families (they got the names and addresses from school districts), as well as to political and media leaders, in an apparent attempt to bolster support for the test. “I can pass the WASL,” reads the front of one postcard, next to a picture of a student.

O’Connor responds to criticism of the test by saying, “The train wreck has already happened. We keep sending kids out there totally unprepared.” Jean Carpenter, the state PTA’s executive director and a WASL critic, concedes the point: “We helped pass education reform; we had kids graduating who couldn’t read and write.” Prominent among them were poor, minority children.

Education reform put superintendents, principals, and teachers on notice: They would have to ensure that all students attain a certain level of proficiency by graduation, and this would be demonstrably measured with a test, what later became the WASL. Eight years later, the federal government weighed in with No Child Left Behind. That act requires states to use their own tests, in our case the WASL, to assess kids in third through eighth grades. Consequently, an even more extensive testing schedule will go into effect this year, adding to the current regimen of tests given primarily in fourth, seventh, and 10th grades. Most significantly, No Child Left Behind mandates that states disaggregate test scores to make sure that minorities and other groups are achieving. States that don’t perform up to snuff face possible loss of federal money. That has put a fire under state bureaucrats. Note, however, that the state, not the feds, made the WASL a graduation requirement, lighting a match under students, too.

While such high stakes ignite controversy, there is enormous appeal to the idea of shaking up the status quo, to insist that historically neglected and underperforming students achieve. “We need to implode the system,” says Seattle Urban League President James Kelly, a WASL supporter. “It’s about high expectations.” For those who complain, including African Americans and others who lament the high failure rate, he has a rejoinder: “The bar has been raised. Get over it.”

Ideally, this would be done with a rigorous curriculum that just happened to have a test associated with it. The most important part of education reform, according to boosters, is not the WASL but new academic standards that lay out for teachers the skills their students should be learning. “It’s the skills, not the scores,” says Kim Schmanke, a spokesperson for state Superintendent of Public Instruction Terry Bergeson. She says Bergeson has challenged herself lately to not even say “WASL.” Says O’Connor of the Partnership for Learning: “If you’re using the standards and using them creatively, there shouldn’t be any cram sessions for the WASL.”

According to this ideal, educators, after blithely teaching the standards without regard to the WASL, would become accountable for their students’ scores—without transferring any of the stress they feel to kids. What a decade of experience with the WASL has shown is that the reality is far different.

A few years ago, in the South King County town of Covington, Regina Herron’s daughter started having sleepless nights. She was in fourth grade, the first big year for the WASL. She would go to bed at 9 o’clock but come into her parents’ room every hour, saying she couldn’t sleep. Though her daughter was a good student, “She fretted about not being able to do well,” Herron recalls. “I just kept telling her, ‘Do your best.'”

Undoubtedly, Herron thinks, her daughter put some of that stress on herself. But she also got a clear message from teachers that the WASL was a big deal. When Herron volunteered in her daughter’s third-grade class, she heard the teacher respond to students’ work saying, “That’s not WASL accepted,” or, “Give me a WASL answer.” For fourth grade, Herron put her in another school, where there was less pressure but which still encouraged students to attend an after-school “WASL academy.” Students in fourth grade are typically 9 years old. This is one of the most troubling aspects about the way the WASL has played out: It causes intense anxiety—a grown-up, your-worth-depends-on-your-performance kind of anxiety—at a young age, younger even than 9. Holly Fudge, a school nurse in the Seattle suburban Northshore district, recalls a child coming into her office last year. “He was in tears, hysterical. He said, ‘I failed my math test.’ I said, ‘Don’t worry about it. It’s the beginning of the year. The teachers just want to see where you are.’ ‘But I’m going to do terrible on the WASL,’ he cried. I said, ‘Oh sweetie, you’re in third grade.'” Fudge’s son began sleepwalking when it came time to take his fourth-grade WASL.

The emphasis on the WASL only grows as kids progress through school and face the looming graduation requirement. Snohomish High School sophomore Ryland Penta, who with a friend constructed an anti-WASL Web site (www.freewebs.com/anti_wasl), says his teachers tell him, “If you don’t pass, you’re going to be stuck here for another year.” The subject is brought up during routine class tests and homework assignments. Penta has reason to worry, because, although he’s an A and B student, he gets panicky during tests and has failed the WASL in previous grades.

In the state PTA survey, parents recounted that their children were told that their future depended on the test, that they wouldn’t be able to go to college without acceptable scores—even, at one Eastside high school, that their performance would affect surrounding property values.

Some parents have protested by opting their children out of the test, a more attractive option before the graduation requirement. Olympia mom Deanna Foley decided to opt out of the public schools entirely. Foley’s fifth-grade son is dyslexic and reads several years behind grade level. Still, he loved school— until the fourth-grade WASL rolled around. “He woke up and didn’t want to go to school,” Foley recalls. “His stomach hurt every day.” The experience taught the child a lesson, and not a good one. “Now he’s finding out that he’s not average,” Foley says. He’s become extremely self-conscious of the fact. At school, he insists on having a grade-level book on his desk, even though he can’t read it. He may not be able to pass the WASL, but it’s important to him that he looks as if he can.

Kids who pass the WASL, kids who don’t. Says Foley: “I have a huge problem with labeling people like that.” She has always figured that the important thing was that her son was making progress. And so, although she loves her son’s elementary school and is the PTA treasurer there, she will begin homeschooling him next year. Neither homeschoolers nor private school students are required to take the WASL. Foley has two other children whom she will homeschool, as well, including a daughter who would enter kindergarten next year and a 7-year-old son whom she calls a “perfect child for the WASL.” She explains, “I just don’t want any of mine around that.”

One could argue that all this pressure might be palatable if it was truly increasing academic rigor and achievement. “It’s fine to be obsessed with the test if it’s for the right reasons,” says the Partnership for Learning’s O’Connor.

Mary Alice Heuschel, deputy superintendent of public instruction, doesn’t exactly say that. She acknowledges that the pressure is out of hand. “We don’t want it to be that way,” she says. The solution, she thinks, lies in training teachers with better “tools and strategies.” Heuschel adds, though, that one of the most effective ways of getting kids to relax about the test is to “give kids practice on the way questions are asked.” This wouldn’t seem to de-emphasize the WASL. In fact, it sounds like an exhortation to teach to the test. Heuschel responds: “If you are teaching the content of the WASL, you’re teaching the standards, which is a good thing.”

A conversation with a half-dozen sophomores in a Rainier Beach High School classroom suggests that WASL preparation can have the effect Heuschel describes. The sophomores, motivated students who are taking an Advanced Placement European history class, view the WASL as a potential barrier to college and participated in a film project last year intended to show the test’s ill effects. Yet as we talk, it becomes apparent that the school’s big push to reverse a record of failure on the test, with such measures as “WASL Wednesdays,” has boosted their confidence. “It’s made me feel that, yes, I can do it,” says Alameda Taamu, who adds that he learned to go back and read questions until he understands them, to write more than one-word answers, and to solve math problems without a calculator. “It’s going to put Rainier Beach on the map in terms of tests,” Brittany Morris chimes in. And those dreams that Brittany has about the WASL, she says, are exciting ones, about going to college.

While that’s an exhilarating voice of optimism from a school usually associated with depressing academic news, their teacher, Paula Scott, points out that these motivated kids are exceptional. Many more kids at Rainier Beach have been failing the WASL by wide margins in prior grades and see little chance of passing the 10th-grade test. She worries about a defeatist attitude that will propel these kids to drop out, not excel.

The jury is still out on whether teaching to the test will benefit kids who need serious remedial help. What is inarguable, though, is that such teaching carries a range of negative effects. Susan Conners can tell you about some of them. She and her family moved from California to South King County’s Normandy Park a few years back. Two of her three children had gotten what she considers a good educational foundation in California. But Nathan, her youngest child, was only in third grade when they arrived in Washington. “I regret bringing him here,” Conners says.

“Nathan’s education in elementary school has been far less broad,” she explains. Since the WASL has primarily tested reading, writing, and math, she says, “The overwhelming part of his day has been spent in nothing but reading, writing, and math, over and over again—and he hates it.” One year, she saw that his schedule allowed a total of 45 minutes a day for health, social studies, and science—combined. “That’s not OK with me,” she told the principal. His response, according to Conners, was that his staff didn’t have time to teach those things because they had to get kids ready for the WASL.

So when Nathan was in the sixth grade, Conners took a two-hour break from the accounting office where she works, picked her son up at school an hour and a half early, and took him home to teach him social studies and science. They did experiments in the kitchen and traced the routes of explorers on the map.

Conners sees a class dimension to the WASL. She recognizes that some struggling students might need intensive practice on basic reading, writing, and math skills. “Only a moron would argue that it’s not important that kids be literate.” Yet, she says, “If your kid is competent in those areas, your child is going to spend lots of time watching other kids learn those things.” At least, she thinks, that is the case in districts like hers, Highline, which has a largely immigrant and working-class population. In California, which also has a student exit exam, she lived in a wealthier district that didn’t have to worry so much about how students would do. She suspects richer districts in this state, too, have a more varied curriculum. She told a school administrator, “I’ve got to move to Bellevue if I want my son to learn history.”

The exclusive focus on reading, writing, math, and now science, as that subject is phased in, also worries teachers, who are concerned that social studies and the arts will go by the wayside. According to Hasse, the WEA president, social studies teachers wonder if they should press for a WASL exam in their subject, too, even though many disagree with high-stakes testing, as a way to get attention for that subject. Meanwhile, schools are telling students to cut arts classes and extracurricular programs so that they can take a WASL prep class or double doses of math and reading.

Shannon Rasmussen, a veteran middle-school teacher who is president of the Federal Way Education Association, talks about a student she had in a drama class: “He was quite talented verbally. I would say he was in the top 10 percent of the class. He was also a special-ed student.” School administrators determined that he was in danger of failing the WASL. So they pulled him out of her drama class twice a week to go to a WASL prep class. On one level, that would seem to make sense. If the kid couldn’t, say, read adequately, isn’t that more important than his theater technique? On the other hand, Rasmussen says, “Here’s this one thing that he’s really good at,” and his ability to do it is restricted.

Even in emphasized subjects, it’s not clear whether the WASL is raising the bar—or lowering it. Rasmussen, who also teaches English, relates the way teachers focus on specific skills that they know will earn high marks on the WASL while neglecting other material. At her prior school, for instance, teachers spent a lot of time making sure that students used the “question stem” in writing exercises. That is, if an essay question asked them, for example, what they thought was the most important thing about their hometown, they would begin by writing, “The most important thing about my hometown is . . . ” Not exactly high-level work.

Rasmussen also says students spent more time analyzing poetry and less time writing their own because that’s what the WASL has them do. “Same thing with creative writing,” she says. In fact, Rasmussen says, teachers discouraged students from writing essays too creatively. Teachers who debriefed kids after the WASL studied their scores and concluded that the formulaic five-paragraph essay—introductory paragraph, three paragraphs of supporting evidence, and a conclusion—was most likely to win a passing mark. “Sometimes kids can pass by being creative,” Rasmussen says, “but they’re a risk.”

A risk? By being creative? Washington Middle School’s Debra Tarpley, who works with immigrant students, laughs at the absurd way she believes she, too, has to teach. “No flourishes,” she says, mimicking her message to kids. “Just keep to the program. Keep it simple. If you can’t spell it, don’t even try it. Use a smaller word.”

State Deputy Superintendent Heuschel says teachers are mistaken in believing that the WASL rewards formulaic writing. “There’s room for wonderful creativity,” she says. But that begs the $64,000 question: Isn’t it inevitable that teachers will teach narrowly to whatever it is they think will win high marks on the WASL as long as their fate, and that of their students, depends on those scores?

It’s not that the WASL is a bad test. It represents, in fact, an innovative attempt to get away from the dull, fill-in-the-bubble, multiple-choice-style tests of old. Like any test, however, it emphasizes a particular set of skills. Prominent among them is showing your abilities through writing, drawing inferences from short passages of text, and solving mathematical word problems. Bellevue Superintendent Riley, who has taken the test, says he found “a big part of it was, ‘Do I know how to reason my way through a question?’ That’s an OK skill to have.” But he doesn’t think that it accurately assesses what students have learned in class. Nor does Riley feel that being able to solve those questions is a good gauge of whether kids will be successful in life. Riley, a pretty successful guy, found himself scratching his head as he tried to figure out what several questions wanted him to do.

“Something’s out of whack,” Riley continues. In his district, roughly two-thirds of last year’s sophomores passed the WASL. “Well, hell, man, I’ve also got 85 percent of kids taking AP courses, my GPAs are high, my SAT scores have gone up 50 points in 10 years. So you ask, are you holding yourself accountable? I say, hell yes. But then you say 35 percent of your kids aren’t going to graduate?”

Who is the WASL benefiting? As Tarpley of Washington Middle School observes, middle-class families are being squeezed out—forced to school their kids elsewhere—because they “want more than a basic, rigid education for their kids.” Meanwhile, she says, “We’re getting killed at the lower end.” And sometimes even bright, motivated students wind up with their spirits squelched.

Tyler Stoken changed after he was suspended from his Aberdeen school for failing to complete that one WASL question. He developed a nervous habit of scratching himself, so sharply that he drew blood. Sitting in the car, he would rock back and forth, crying. “I’d never seen him crying like that before,” says mom Amy Wolfe. He spent the following summer in counseling.

He also told his mom he was scared to go back to school because everybody would be mad at him for dragging down their scores. So the district sent an aide to work with him at home for the rest of the year. He’s back at school now but has become insecure about his abilities. “He gives up on stuff a lot easier now,” says his dad, Jason Stoken.

Meanwhile, Wolfe, who used to run a small trucking business with Tyler’s dad but now stays home with Tyler and his brother, has become radicalized by her son’s experience. She’s hooked up with a group called Mothers Against the WASL, led by Spanaway resident and onetime candidate for state superintendent Juanita Doyon. Wolfe is planning to start a local chapter with the “girls,” as she calls her compatriots.

Principal Olivia McCarthy, Wolfe says, has never apologized. McCarthy did not respond to requests for comment. Wolfe did receive a written letter of apology, though, from Aberdeen Superintendent Marty Kay. The letter eloquently expresses some of the dangers of high-stakes testing. “We need to put tests in their proper perspective and help students understand the role of tests, so that our students are not made to think these tests measure their ability to learn, their potential to be successful, or their value as people,” it reads. “Education is failing when tests are more important than the students themselves.”