If one had to conduct a case-study in political invulnerability, King County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg would be an obvious choice. First elected in 2007 after succeeding former longtime county prosecutor Norm Maleng (who died in office), Satterberg has earned a reputation as a criminal-justice reformer among some local progressives despite his past affiliation with the Republican party. More notably, he has not garnered a single electoral challenger since his first run.

“It has astounded me as a politico to look at how he has managed to not step on a land mine,” said longtime King County Councilmember Pete von Reichbauer. “It’s a county dominated by a strong Democratic edge, and yet he has not had major competition.”

High-profile examples of Satterberg’s criminal-justice reform efforts include his support of the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion Program (which directs low-level drug offenders to social workers and case managers instead of into the justice system), supervised safe consumption sites for drug users, and banning the death penalty statewide.

These efforts have prompted praise from reform advocates. “Dan has a very strong track record,” Lisa Daugaard, director of the Public Defender Association and a co-founder of Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion Program (LEAD), told Seattle Weekly. “He has been a leader and a initiator of criminal-justice reform work.” Even Satterberg’s chief adversary within the justice system, King County Public Defender Lorinda Youngcourt, said that he is “one of the most progressive prosecutors” that she’s ever worked with.

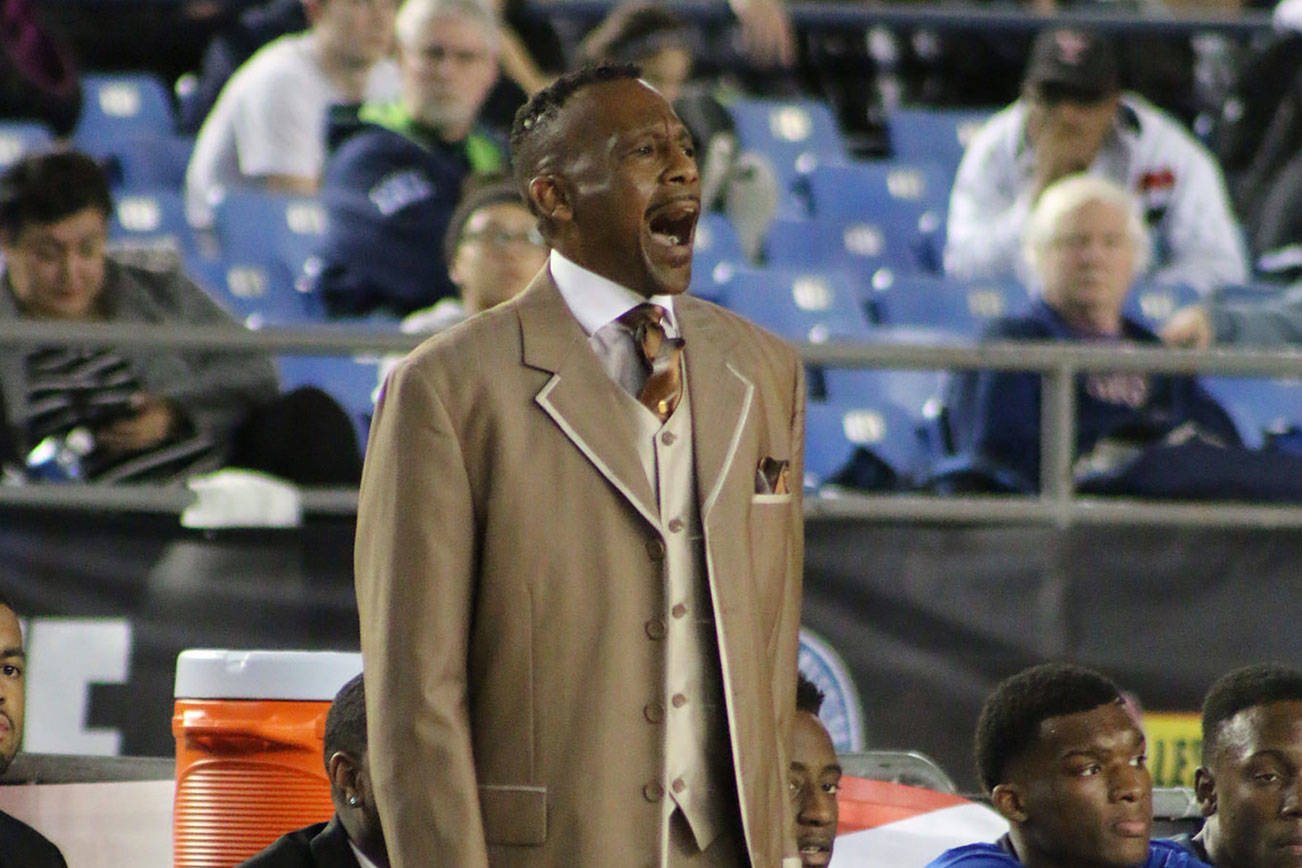

But after over a decade in his seat, he will now have to defend his record against 45-year-old public defender Daron Morris, who alleges that Satterberg’s reformer credentials are overstated and new blood is needed to address systemic issues such as racial disparities in the justice system and county detention facilities. (African Americans are overrepresented in bookings to county detention facilities, for example.)

“I want to focus this discussion on real reform because the conversation we’re having right now isn’t addressing the things that ought to be concerned about,” Morris told Seattle Weekly. “The problems that I’m talking about: mass incarceration, institutional racism, fairness in community. The reforms that are happening right now are not headed in the direction of fixing those problems. … They address maybe the tip of the iceberg, but they leave the iceberg.”

In a more direct criticism of Satterberg, Morris accuses him on his campaign website of pursuing reforms only when they are politically convenient. “Our King County Prosecutor has only moved forward only where it is to his advantage to do so, only half-heartedly, and only at the very margins of the deep and horrible problems facing our justice system.”

As a former public defender, Morris comes from the side of the justice system that is the perpetual and innate adversary of county prosecutors. After going to law school at New York University, Morris worked at NYC’s Legal Aid Society, and eventually moved to Seattle in 2001, working in various sectors of the King County Public Defense Office. He resigned his post at the Department of Public Defense shortly before he announced his candidacy in May.

“I’ve been a public defender for 20 years and I have been representing my community. Which I think is really important, because as a public defender you really see the faces of those people and hear their stories,” Morris said. “What I’m hearing from everyone I talk to—and what I feel myself—is that community trust in our justice institutions is very much eroded and that’s making us less safe.”

His platform includes opposing the controversial new county youth detention center in Seattle (instead, he wants to develop a series of “justice centers” with a “flexible array of courtrooms and options” across King County), generally reducing sentences for young adults, and limiting plea bargaining and ending prosecutor requests for bail for defendants unless absolutely necessary. Additionally, Morris said he’d conduct extensive community outreach to garner public feedback.

Citing the enthusiasm generated for lawyer and activist Nikkita Oliver’s 2017 mayoral bid, the energy of the ongoing No New Youth Jail campaign, and national debates about criminal-justice reform, Morris says he’s in the campaign to win and not just raise contemporary progressive issues. “I intend to win this election through and on behalf of the community—and particularly the most vulnerable communities,” he said.

But it’s going to be a severe uphill battle for Morris given Satterberg’s entrenched incumbency and practically universal positive reputation among a variety of local political heavy weights. Not only does Satterberg currently have a campaign war chest of over $80,000 (Morris has so far raised around $14,000, according to the Public Disclosure Commission), and he has the support of the likes of Daugaard, state Attorney General Bob Ferguson, and civil rights activist and King County Councilmember Larry Gossett (who told Seattle Weekly that he would be “very surprised” if it’s a close race).

Regional political consultant and analyst Ben Anderstone said that voters associate Satterberg with a type of moderate Republican that few would recognize in today’s Trump-led GOP. “He is kind of in the legacy of the [former Washington Governor] Dan Evans-era of Republicans, back when there was this streak of Republicans in Washington state that were seen as effective, almost ideologically neutral public servants,” says Anderstone. “Dan has been viewed in that vein by the electorate in the past.”

Councilmember von Reichbauer said that Satterberg inherited the tactics and style of former County Prosecutor Norm Maleng from working as his right-hand man for so long. “Norm was respected and liked by everyone,” he said. “Dan inherited that good will and was smart enough to also inherit Norm’s skillful ability to work with both sides of the isle on issues.”

During his 28 years as county prosecutor, Maleng also ran unopposed in almost all of his races (save for his 1998 race where he won by 17 points) after first getting elected in 1978. Also a Republican, he established new programs like prosecution units for sexual assault and domestic violence, helped build the county drug court system, and was regarded as constrained in his pursuit of the death penalty. When he died in 2007 of cardiac arrest, prominent Democrats such as Jenny Durkan and former state Democratic Party chairman Dwight Pelz commended his legacy, speaking to his bipartisan appeal.

Sandeep Kaushik, a veteran local political consultant who worked on the campaign of Democrat Bill Sherman, a former attorney in the prosecutor’s office who ran against Satterberg during that initial 2007 election, told Seattle Weekly that Satterberg built his campaign on his close association with Melang. “What Dan really ran on was ‘I am Norm Melang’s anointed successor.’ His TV ad was him and Norm,” he said.

After winning his post in 2007, Satterberg combined a willingness to push the envelope on criminal-justice reform with a pursuit of more traditional punitive initiatives. He advocated for clemency for some individuals serving life sentences in his early years in office. He also helped establish both the successful 180 Program (which allows minors to get misdemeanor charges waived if they go through a series of diversion workshops) and the LEAD program in 2011. On the more traditional end of Satterberg’s prosecutorial spectrum, he’s pursued aggressive crackdowns on regional car theft and tougher sentences for juveniles with illegal guns.

This isn’t to say that his tenure has been without controversy from regional progressives. In 2011 Satterberg declined to prosecute the Seattle Police Department Officer, Ian Birk, who fatally shot John T. Williams, a Native American woodcarver, arguing in a public memo that his office did not have evidence that Birk acted with “malice” in shooting Williams, as state law then required for prosecution of officers who kill. “Under the legal standard applicable at the time, it would have been very hard to obtain a conviction. But I think the public wanted to see those in authority do everything they could to hold Ian Birk accountable,” then-Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn told Seattle Weekly. In 2017, Satterberg eventually explicitly endorsed changing a statute to make it easier to prosecute cops.

Then there’s his office’s stance of cracking down on the demand side of prostitution by arresting buyers and shutting down sex-trade websites. The move came after accepting grant money from an anti-prostitution organization, garnering extreme criticism from sex-worker advocates. Of the strategy, Morris says on his website that Satterberg “isn’t listening to women.” Satterberg has long contended that the industry is inherently exploitative and should be eliminated without directly prosecuting sex workers.

The prosecutor himself plays up his both his nonpartisan and reformer credentials. “One of my strengths as an office holder is that I don’t want to be anything else. I want to be the prosecuting attorney. I don’t have a political motivation behind wanting to sit down and talk with someone,” Satterberg said in an interview. “I’ve been willing to question why we do things the way we do them and to consider other paths.”

But he wasn’t always the darling of some criminal-justice reformers. Daugaard with the Public Defenders Association said that he’s changed quite a bit since his early days as Maleng’s chief of staff. “I vividly recall back in 2001, Dan and I were both on a panel that the King County Bar Association sponsored on drug policy reform … I walked away from that panel thinking that, ‘When Norm Maleng retires, I hope Dan doesn’t become prosecutor,’ ” she said. “Back then he didn’t have that breadth of vision and openness that he does now.”

Some chalk Satterberg’s stated open-mindedness to a degree of politically tactical maneuvering. David Mendoza, a marijuana-policy advisor to former Seattle Mayor Ed Murray, told Seattle Weekly that Satterberg declined to crack down on local illegal marijuana-delivery operations that sprouted after statewide legalization out of fear of potential public criticism of prosecuting activity involving a recently decriminalized substance. “I remember one meeting where he told us, ‘Who are we to prosecute anything when the state is selling this stuff?’” Mendoza said. “This was my read on that: A lot of it was him not wanting to face backlash.” (Satterberg told Seattle Weekly that the decision was based on “justice” rather than political advantage.)

While Satterberg may deny operating based on optics, certain maneuverings belie that point. On May 29, Satterberg told The Seattle Times that, after running in 2007 as a Republican, he now identifies as a Democrat. “I don’t want anybody to think for a second that my views are in line with this president,” he told Seattle Weekly. “As a reflection of what my personal values are and my political values, I am a Democrat. No hesitation in saying that.” (Satterberg also pushed for a charter amendment that was approved by the voters back in 2016 that officially made the prosecutor’s office nonpartisan.)

“He’s very aware that he operates in a progressive-left environment,” political consultant Kaushik said of Satterberg.

Despite the praise he receives, public defense attorneys still have criticisms about the way Satterberg runs his office that back up many elements of Morris’ platform—such as the the alleged use of excessive bail. “I’d like to see us end money bail. He has the ability to instruct his folks not to request money bail on lesser crimes,” said county public defender Youngcourt.

John Marlow, a Department of Public Defense attorney, told Seattle Weekly that he frequently witnesses county prosecutors request that defendants’ bail be set in the thousands of dollars for felony-quantity drug possession charges. “The State’s requests for drug charges often can and do range from $5,000 to $25,000,” Marlow wrote in an email.

When asked about Marlow’s concerns, Satterberg denied that steep bail figures are routinely requested by his attorneys for drug-possession charges. “People are not held on bail,” he said, adding that few drug-possession cases are actually prosecuted as felonies, and that bail is requested by his attorneys only if the defendants have extensive criminal histories and have frequently failed to appear in court.

Whether or not such issues will be enough to take down a political giant like Satterberg remains to be seen, but Morris has already made inroads with local Democrats and earned endorsements from the 46th, 43rd, 37th, and 36th legislative district Democrats, showing that he is gaining some traction.

Political analyst Anderstone said that the Democratic electorate may be less willing to stand with Satterberg uniformly than they have in the past. “Although Dan’s position on criminal justice has been arguably not even to the right of average Seattle voters … his approach to law enforcement is still incrementalist and institutionalist,” he said. “There are more and more people on the left who feel that the issues in law enforcement are so systemic that being incremental is not enough.”

jkelety@seattleweekly.com