Skyway Park Bowl sits beige and inconspicuous off Renton Avenue South, between a casino and an Ezell’s Fried Chicken. It’s Wednesday night, and in the lounge drinks are being poured to a soundtrack of clattering pins and 2 Chainz. The clientele is as diverse as the neighborhood around it. On the Route 106 bus there, I detected no fewer than four languages being spoken around me—that’s counting English, some of which was freestyled by a group of high-school kids heading home from school. As of the 2010 census, the Bryn Mawr-Skyway neighborhood was almost perfectly diverse: 29 percent white, 31 percent black, 27 percent Asian, 7 percent Hispanic.

On this night, in an incongruous conference room next to the bar, the presidential campaign of Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders has scheduled a “barnstorming” event. Organizers have invited people in the surrounding neighborhoods to come out, talk Bernie, and see what they can do to propel Sanders to victory in Washington state’s upcoming Democratic caucuses on March 26. For my part, I’ve come out to plum the depth of two narratives dogging the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign—one as old as the campaign itself, the other as fresh as the returns from last night’s primaries.

The old one is that Sanders has a race problem. While he’s clearly moved on from the colorblind politics that led to last summer’s viral “Bernus Interuptus” in Westlake—during which two Black Lives Matter activists shut down his rally to bring attention to the killing of black men and women by police—exit polling has shown a continued disconnect between the senator from Vermont (94 percent white) and minority voters. The night before, in a string of primary losses for Sanders, blacks supported Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton by margins of 79-20, 68-30, and 81-17 in Florida, Ohio, and North Carolina, respectively. In heavily Latino Florida, Clinton won that demographic’s vote 72-28.

Which leads to the second, newer narrative, pressed hard by the Clinton campaign in the immediate aftermath: Clinton’s victories in four of the five states, aided in large part by the minority vote, was a knockout punch to the aspirational Sanders campaign (Clinton would later claim victory in the fifth state, Missouri, as well).

“The bottom-line results from last night: Hillary Clinton’s pledged delegates lead grew by more than 40 percent, to a lead of more than 300, leaving Sen. Sanders overwhelmingly behind in the nomination contest—and without a clear path to catching up,” Robby Mook, Clinton’s campaign manager, wrote in a memo sent to the press.

The Sanders campaign retorted vigorously, putting forth its own delegate math that suggested a plausible but difficult path to the nomination, part of which is contingent on wide victories in states like Washington that could net significant delegate counts. Yet I was curious how the previous night’s primaries were resonating among the foot soldiers who had been so vital to Sanders’ campaign; after all, it’s always the generals who are last to admit defeat.

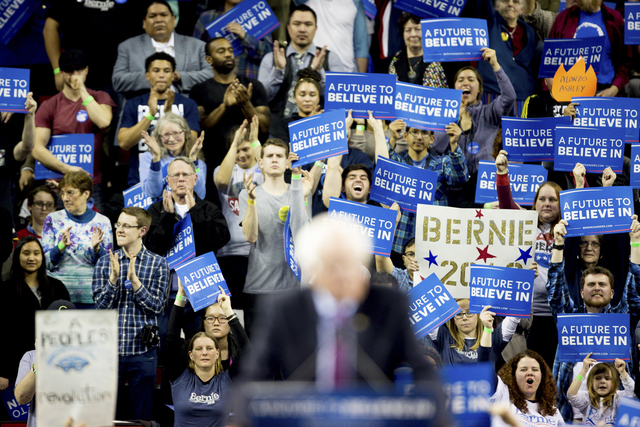

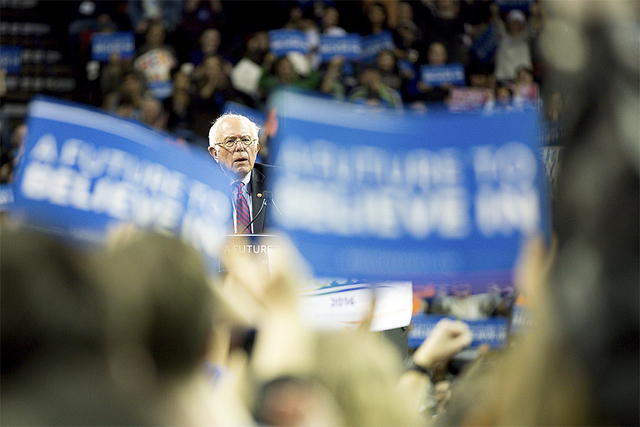

The Sanders event kicks off at 6 p.m., and soon any thought that his supporters would be discouraged by the night before dissipates.

If it’s not the rowdy electoral orgy that “barnstorm” connotes, the crowd is big enough to fill the room with nearly five dozen supporters. They’ve come out because they feel Sanders is the only honest candidate in the race, the only one who had come out firmly and unequivocally against fracking and Goldman Sachs. The Trans-Pacific Partnership free-trade agreement, which Sanders strongly opposes, is on their tongues and conspiracy theories about rigged votes in Florida and Illinois in their whispers.

“He’s inclusive, he doesn’t want build a wall, he’s not afraid of Muslims. Muslims love him. He’s Jewish and they love him!” says Kim Naranjo, a self-described “recovering CPA” from South Seattle. “I need him to have a shot.”

The soldiers will march on.

However, enthusiastic as the crowd is, there is no ignoring the demographics of the fluorescent-lit conference room, made all the more impossible to miss when contrasted with the demographics of the bowling alley and lounge outside its doors. From a very superficial count that errs on the side of minority, I place the room at about 75 percent white. While it’s true that the invitation for the event extended beyond Skyway—to places like Burien, Renton, and Rainier Beach—those ZIP codes hardly explain away why this is almost no doubt the whitest room on Renton Avenue South tonight.

“I’m not surprised by the make up of the crowd. It’s a young crowd, a diverse crowd. What’s discouraging is the lack of African-American people,” says Rev. Dorinda Henry, herself African-American. “Why is there this blind allegiance to Hillary Clinton when she has time and time again shown herself to be unkind to the African-American community?”

For not the first time in my reporting, I am reminded of Clinton’s instrumental role in her husband’s criminal reform policies, which have been blamed for the explosion of black men behind bars in this country. Sanders, meanwhile, has been fighting for civil rights since the 1960s, Henry notes, and holds economic policies that she says will bring real change to minorities.

“If the hip-hop community comes out and supports Bernie Sanders and works to get the word out about Bernie Sanders, he will win California and New York,” Henry says. “If the hip-hop culture comes out strong, this election will be over.”

But at this moment, in this place, the only hip-hop coming out strong is the music in the bar, through the walls.

There is little doubt that Sanders is going to win the Washington caucus this Saturday. Back in February, The Seattle Times reported that Washington voters have given more money to the Sanders campaign than those of all other states combined; more recently, the Times—whose notoriously conservative editorial board recently, inexplicably, endorsed Sanders—reported that Seattle was giving more per capita to Sanders than any other major city.

In the memo in which Clinton campaign manager Mook declared Sanders vanquished, he all but conceded that Sanders was going to win this state. “Looking ahead to the rest of March, Sen. Sanders is poised to have a stretch of very favorable states vote, including five caucuses next week, which he is likely to win,” Mook wrote, by way of saying that those wins won’t matter.

Yet as strongly as Sanders is poised to perform in Washington and especially Seattle, the returns may also expose a paradoxical fact of the socialism that Sanders preaches and our city has embraced: that it’s a phenomenon driven by white, educated voters, a demographic that as a whole is doing quite well for itself in the capitalist system as now constructed—a fact especially evident in boom town Seattle.

It’s a paradox that cuts both ways. Much as Henry is baffled by African-Americans’ resistance to a candidate whom she sees as the only one who will get serious about the economic inequality that plagues black Americans, a North Seattleite may reasonably wonder why a city that is clearly benefiting from the New World Order—free trade, automation, code—is so strongly backing a candidate whose platform is constructed around the idea that today’s economy is a sham.

“If you look at the top donating cities for Sanders, it’s Seattle, San Francisco. They’re doing pretty well in the new economy,” notes Ben Anderstone, a political consultant with Progressive Strategies NW in Seattle. “You’re not seeing Pittsburgh on that list.”

Of course, in some ways it’s hardly surprising that Seattle has gotten firmly behind a Socialist. It’s more notable when it looks as if Seattle is abandoning its pinko tendencies, not cottoning to them. In 1996, in The New York Times, Timothy Egan traced the founding of outdoor gear cooperative REI to “the Scandinavian socialism of the Pacific Northwest” before discoursing on how the company’s breakneck growth represented a possible shift toward more capitalist impulses. (Headline: “Is Hiker’s Shop a Paradise Lost?”) In this paper, in 1999, famed political columnist Shelby Scates wondered whether the flood of migrants into Cascadia—1.2 million people moved to Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia between 1990 and 1996—was turning what a Democratic pol in the ’30s called “the Soviet of Washington” into a red state of a different hue. (Headline: “Progressives’ Paradise Lost?” Forgive them, John Milton, for they know not what they do.)

But for all those supposedly lost paradises, Seattle has continued to show it’s not allergic to socialism as a political ethos. In 2013 we elected Socialist Alternative candidate Kshama Sawant to the City Council, then did it again in 2015, and have gotten behind this Democratic Socialist for president in a superlative way.

All while seeing the median income increase 35 percent between 2000 and 2013 in King County.

Of course, in our current economic system, a rising tide does not lift all boats. Perhaps the people donating to the Sanders campaign are those Seattleites who are getting burned by the techie invasion. But the data (what else?) would suggest South Lake Union is feeling the Bern as much as anyone.

When donors give to political campaigns, they must note whom they’re employed by. According to Open Secrets, when counting contributions by both individuals employed by a company and that company itself, the top donor to the Sanders campaign is Alphabet (the parent company to Google). Apple is third, followed by Microsoft and Amazon (the entire University of California system is second).

Sanders has not declared all-out war against corporate America, let alone Big Tech. A program developer cutting a check for Sanders is not inherently dooming the giant company that, in turn, cuts her checks. But there is no denying that major corporations bear the brunt of his rhetoric, and will probably feel the bern if he’s elected.

“The CEOs of large multinationals may like Hillary, but they ain’t gonna like me,” Sanders said to cheers during a debate in December.

The specter of well-to-do Amazonians turning out for the would-be scourge of corporations hasn’t entirely escaped notice.

“Some of the [Sanders supporters] I’ve seen are people who work for big business. If you can live on Capitol Hill and pay $3,200 a month, then you’re part of big business,” says Charmaine Slye, a Capitol Hill resident and Clinton supporter. “Here you are, you’re making tons of money, and you think Hillary is the bad person?”

There is an annoying tendency in liberal culture—of which I consider myself a member—to grouse about poor people voting against their own economic interests (read: supporting Republicans) while celebrating rich people who vote against theirs (read: Warren Buffett.)

But Anderstone says that such thinking frames the question wrongly: It’s not that people vote against their economic best interest. It’s that economic interests don’t often play a primary role in how people vote.

“In the last 15 years, we have seen a big disconnect between what you see on paper who would benefit the voters economically and how they vote,” says Anderstone. “It’s especially stark in Washington state—the areas that have most benefited from free trade, for example, the most wealthy areas,” are more inclined to support candidates who take a skeptical stand on free trade.

“Ultimately,” Anderstone continues, “people vote less on their self-interest than on their ideals and values. Ultimately, Seattle likes candidates informed by a social and economic-justice angle. Candidates who push the Democratic Party leftward. If you look at the candidates on paper and how that aligns with the interests of Seattle, Sanders would have a hard time. But voters in Seattle aren’t thinking about their tax returns and their stock portfolios when they back a candidate.”

Longtime political consultant Christian Sinderman says Seattle’s recent voting record displays this tendency to put social justice over economic interests. “Clearly there’s a communitarian spirit in this city,” says Sinderman, who led Washington House Speaker Frank Chopp’s successful re-election campaign against Socialist Alternative candidate Jess Spear and consulted Pamela Banks on her unsuccessful challenge of Sawant. “You look at the consistent adoption of tax levies. For kids or parks or schools or transportation systems or affordable housing. There is a willingness to reinvest and quite literally share the wealth with all.

“Are people in Seattle angry about the rich getting richer, or the poor falling behind? Yes. And they should be.”

But if all this helps explain why a rich city is supporting a champion of the poor, it doesn’t get us any closer to why minorities—who statistically are at a greater risk of suffering from poverty—don’t seem to be totally on board with Sanders or, indeed, socialism in general.

Looking back at 2013, when Sawant shocked sitting councilmember Richard Conlin in a city-wide election, Sinderman says it was whites who came out most strongly for the socialist—herself an immigrant from India. “The strongest support for Kshama Sawant was really among younger, whiter populations. Even in southeast Seattle, where she did well, it was in gentrifying neighborhoods, more so than traditional African-American or Asian-American neighborhoods,” he says. “I think Sawant’s numbers are relatively indicative of where Sanders will find support in Seattle: Capitol Hill down through southeast Seattle, north into the U District, Wallingford, and Fremont.” (While Sinderman consulted on Banks’ campaign in 2015, he was not involved in the Conlin/Sawant race).

Sawant’s office disputes Sinderman’s analysis of the 2013 election. Last year, Sawant claims she beat out Banks, who is black, in traditionally African American neighborhoods in the Central District. While exit-polling data does not exist for city council races, she tells Seattle Weekly that she had the support of the “vast majority of African American voters” in District 3.

Still, in a phone conversation, Banks, who is CEO of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, contends that socialism “doesn’t resonate” with many black voters. She doesn’t have a firm answer to why that is. It could be a lack of education about the subject, she says. But she also advances a provocative—if admittedly speculative—theory: When people are closer to the margins of society, they are more reticent to take political risks.

“Thinking about the affluent white progressive socialist Democrats I met—and I don’t have proof—but I think maybe they feel like they made it, they’ve got their big house, they got their Tesla car, they’re not going to lose their health care, their 401k. They can vote crazy, vote non-mainstream. They want to use our city as a socialist petri dish,” she says. African-Americans, she suggests, don’t have that privilege.

All this said, Banks says she’s still undecided between Sanders and Clinton. Like Rev. Henry, she’s given pause by Clinton’s role in the crime policies of the 1990s that put so many black men behind bars. And skepticism toward socialism notwithstanding, she thinks that the election returns so far don’t speak to anti-Bernie sentiment among blacks but to a deep connection with the Clinton family. “They’re fond of [Bill] Clinton. When he left office, he moved to Harlem. That was a big deal! People are very nostalgic,” she says.

An election is a numbers game: Votes are cast and tallied. Whoever has the largest figure beside his or her name is declared the victor. As such, a great deal of politics, and political reporting, comes down to adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing various blocs of voters to suss out winners and losers, constituents and opponents. It’s a fundamentally impersonal process that chafes against the deeply personal nature of voting. Norman Mailer once wrote to the effect that when we are in the voting booth we are alone, and therefore close to God. And yet for all that you end up a statistic in an exit poll, a generalization in a newspaper article.

Back at the Skyway Park Bowl, while the racial makeup of the crowd does make for easy punditry, in other ways the clutch of people taking time out of their lives to engage in democracy resists it. It does not seem to be a room awash in money and advanced degrees—though such things are more difficult than race to determine from a reporter’s perch. The room does feel earnest, weighed down with serious purpose (and the numbing nuances of how a presidential caucus works). For all the ways a demographer could slice them into subcategories, they are united in a belief that their country needs Bernie Sanders, and that in this way they can help their country.

I make small talk with a man named Mark Velez, who has an easy Southern California demeanor and works at Shoreline Community College in the automotive training program. He has a mortgage and a long commute and doesn’t know where to begin when it comes to why he supports Bernie Sanders. What it comes down to is Sanders’ honesty, he eventually says.

“It’s like with fracking. He just says, ‘No, I’m against it.’ That’s it. None of this … ” he makes back-and-forth motion with his head to indicate a politician trying to avoid a firm stand.

Henry, too, must pause before answering why she’s for Sanders. After a deep breath, she starts. “Bernie Sanders speaks my love language. I’ve been a social- and political-justice advocate for most of my life. This is the first time in my life I’ve had the opportunity to vote for a candidate with a history of social-justice work and political advocacy that Bernie Sanders has. I see this as someone who’s put his body on the line. He’s stood on the right side of justice.

“When he gets into the White House, he’s not going to forget the people he spoke for.”

What’s yet to be seen—and to be watched for on Saturday—is whether those people he speaks for will turn out to get him to the White House.