It’s Sunday, and Seattle race-car fans have gathered for worship at a North End NASCAR bar. In the parking lot, big trucks and SUVs outnumber the Japanese sedans they could crush like Godzilla. Inside, folks belly up beneath a sign with a Ben Franklin quote (“Beer is proof that God loves us and wants us to be happy”) and a NASCAR betting board, to razz each other with one eye on the TV’s racetrack action.

“I used to live in Arkansas. . . . “

“Is that where your mom and dad got divorced, and they were still brother and sister?”

“They were cousins, dammit!”

The ex-Arkansan is a die-hard fan—”I’ve got, like, 400 hats, and I bet 50 of ’em are NASCAR!” He tries to explain that stock-car racing, which first kicked up dust on moonshiners’ back roads, has hit the interstate and zoomed nationwide, overtaking pro football as the new American religion. “I used to truck drive, and we’d watch NFL at bars. Now, you look for a bar, and it’s got eight TVs, and seven are on NASCAR and one waaay in the corner is on NFL.” And if you look for the next bar, a couple blocks south on Bothell Way, you’ll find it is also a NASCAR bar; inside, a dentally challenged guy growls his explanation for the NFL’s decline and NASCAR’s ascent: “It’s cuz football is European. And this [sloshing his beer toward the screen] is American!”

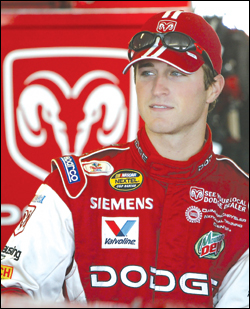

NASCAR—the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (no, it doesn’t stand for Non-Athletic Sport Centered Around Rednecks) is also, increasingly, Northwestern. By Christmas, the Daytona, Fla.–based International Speedway Corp. (ISC) hopes to announce its new Seattle-area NASCAR racetrack site, in either Snohomish, Kitsap, or Thurston counties. The sport’s fastest-rising rookie is Enumclaw’s own cherubic cutie Kasey Kahne, 24, the cover boy of American Thunder magazine, and 70,000 fans may be thundering his name soon at a track near you. Seattle research firm Berk & Associates estimates that if the Puget Sound track could sell out two national races and less-than-half-fill one local event per year, it would rake in revenues of about $87 million to $121 million a year, more than $65 million of it new money from out-of-state fans. The upbeat ISC claims the total economic impact of a typical NASCAR racetrack can reach $400 million a year. And the flag-waving crowd loves that NASCAR does it all without fancy-pants French Grand Prix fag wagons or Japanese rice rockets—just good, honest, red-blooded muscle cars from Detroit, souped-up versions of what they’ve got in the garage and polish each weekend more passionately than they caress their own wives.

The Dixiefication of America

“Get the folks at Starbucks involved with this speedway!” urges Mark Howell, author of the NASCAR history From Moonshine to Madison Avenue. “Putting their name on a race or a race team would be a huge opportunity for exposure! As long as fans threw their empty cups away properly, I don’t think NASCAR would have a problem at all.”

Three Puget Sound counties are vying to become home to a new Northwest NASCAR racetrack—part of the sport’s strategy to broaden its reach beyond its Southern-fried base. |

But NASCAR fans are notorious for pelting drivers with Budweiser cans for being insufficiently all-American. Littering, open defiance of public niceness, and consumption of nonimported, nonmicrobrew beer: What could be more un-Seattle? University of Cincinnati sociologist Rhys Williams sees such traditions as Southern in nature, and NASCAR’s spread as a Dixiefication of the nation—an exporting of “this cultural ethos of guns, cars, and Republican politics and masculinity that just has a stranglehold on the South.”

How will this historic cultural collision play out here? Will Latte Alley turn into Thunder Road? Will NASCAR Dads drive out Soccer Moms in a state that sent one to the U.S. Senate? Are the stock-car invaders white-trash Visigoths, “some kind of manifestation of the animal irresponsibility of the lower orders” (as Tom Wolfe put it in a classic 1965 NASCAR essay)? Will yahoos who don’t use Yahoo! fume up our pristine air, pinch our uppity educated women on the butt, fire Smith & Wessons from the Smith Tower, replace our rainbow coalitions with rainbow oil stains, and violate sound ordinances by gunning the gas-guzzlingest cars in the universe? Is it time to retire our colors and hoist the Confederate flag over Olympia? Or must we throw a red flag at the blue-collar, red-state rednecks for crashing the green party of Ecotopia?

Relax, says state Rep. Hans Dunshee, a Democrat from racetrack-coveting Snohomish. “I don’t think it’s like the South is finally winning the Civil War or anything. There are plenty of blue-state people at [NASCAR] events. You have the wrong image of Democrats, because Democrats also include the union member who hunts and watches NASCAR and drinks beer.” If the fans seem alien to us, it’s because we’re alienated from the culture beyond the borders of King County. “Bluntly, you come from a place where there are lots of Free Tibet stickers. There are a lot more 3s and 8s [the car numbers of late racing saint Dale Earnhardt and son Dale Earnhardt Jr.] in my district than Free Tibet stickers.” If a NASCAR track ever does come to exurban Puget Sound, predicts Dunshee, “I could take the 80,000 people in the stand[s] , and I’ll bet the majority of them will have voted for a Democratic candidate out of Washington.”

But it was Bill Clinton who got booed at a NASCAR event, not drunk-driver-turned-NASCAR-fan-in-chief George W. Bush, whom California writer Jim Washburn calls a “NASCAR Nazi who talks about Jesus while acting like a Roman emperor.” The thing is, Southern or not, Republican or not, NASCAR types tend to like Jesus, and Bush’s muscular Christianity and toga-party imperial style go over big among the impotent. Says sociologist Williams, “The more American men feel threatened by whatever it is—ethnic minorities, women’s empowerment, or not bein’ the top dog on the world block anymore—these sorts of expressions of American masculinity are going to be increasingly popular.” No surprise, then, that Viagra is a NASCAR sponsor—with, until recently, a driver named Mike Bliss.

Obviously, Democrats are going to represent the economic interests of the middle class (indeed, the bottom 99 percent) more robustly than Republicans, but politics is no longer about actual interests. Now it’s about symbols and psychology. And suckers: As Thomas Frank noted in a recent Harper’s, Bushies have conned workers into screwing themselves out of jobs to benefit big-buck bosses, “like a French Revolution in reverse—one in which the sans-culottes pour down the streets demanding more power to the aristocracy.” Though job outsourcing, gas price hikes, the Iraq fiasco, and NASCAR fans’ overrepresentation among American war casualties do potentially undermine their Bush worship, their two-fisted individualism fits niftily into the Republican myth-mongering machine. That, and the fact that they’re practically all white. (“The only place in NASCAR where you will find black and white together is on a checkered flag,” notes the San Jose Mercury News.)

Forget “Free Tibet.” The ultimate NASCAR bumper stickers are “3” and “8,” the numbers on the Earnhardts’ cars. |

Granted, sponsoring a NASCAR car helped elect Connecticut Yankee Mark Warner, the first Democratic Virginia governor (or Senate candidate) in a generation to sway white rural voters and kick Republican butt. However, a “Bob Graham for President” NASCAR truck didn’t do the trick for Florida’s anti–Iraq war candidate. Democratic pollster Celinda Lake famously claimed that the “NASCAR Dad” could be this election’s Soccer Mom, clinching a Democratic victory. But a Kerry victory? I doubt it. “In an era of uncertainty about many things,” notes Williams, “NASCAR seems solid, strong, bold.” Is that how Kerry seems to a NASCAR fan? Or would he seem mushy, wimpy, mealymouthed—the kind of wuss who thinks there’s more than one kinda Arab, disrespects guns and medals, and doubts Saddam was Osama’s 9/11 copilot? Hell, maybe Kerry has conniving plans to require safety equipment in NASCAR cars. What’s next—speed limits? Bush is good at coming off like Huck Finn male bonding with the Bubbas; Kerry is good at sounding like Aunt Sally with the vapors.

NASCAR MEETS NASDAQ

Yet Dunshee is right to say that NASCAR is not a wholly owned Republican satrapy, nor entirely Southern-fried (despite the Colonel’s new NASCAR ad campaign). It’s gotten too big. Thanks to what officials call “the Realignment”—sort of a Reconstruction in reverse—the sport is truly national: New racetracks near Los Angeles and Chicago have displaced races in North Carolina. Sixty percent of the 75 million fans NASCAR claims live outside its original Southeast homeland.

It is true that Confederate flags sprout so profusely at NASCAR that Time likened the Talladega Racetrack to a Klan rally. But the infamous flag doesn’t necessarily signify the same thing in a new national context. When a NASCAR fan from British Columbia was recently spotted waving a rebel flag, it can’t have meant to him what it meant to George Wallace in 1965. “The talk about the Confederacy stuff, that gets all muddled up,” says Dunshee. He’s got credibility on this subject: When he discovered that a local section of Highway 99 was actually named the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway (back in 1939), he spearheaded the 2002 fight to rename it. Dunshee sees no such problem with NASCAR–style Confederate flags.

“There’s a kid who goes by on the street out in front of me with two big ones flying, and he probably knows squat about history, right?” And just who does this kid think his Dixie flags say he is? “Sort of an outsider, a rebel, you know, that’s all they know about it, I think.” If today’s rebel-with-a-flag stands for tobacco rights, it’s the right to smoke it, not grow it with slave labor. If he wants something to rise again, it’s not the South, it’s the Intimidator, Dale Earnhardt Sr.

And at heart, when the chips are really down, NASCAR fans know which flag they rally round: In his NASCAR chronicle, Fixin’ to Git, Jim Wright applauds the “surprising near-total absence of Confederate flags at the October 2001 race at Charlotte, N.C., the first race I attended after the terrorist attack on America.”

But ordinarily, NASCAR iconography glorifies the loner defying authority, not togetherness of any kind. Kate Thompson, the Seattle-area designer of the first NASCAR Web site, says, “The NASCAR aesthetic is primary colors and T-shirts with the American flag and a picture of a wolf on top, a Harley on top of that, and your favorite driver, with LIVE FREE OR DIE on top of that. It’s all about your driver—nobody follows NASCAR, it’s your particular driver, or dynasty, like the Earnhardts. NASCAR is seen as an evil daddy.” Kind of like the federal government, or Aunt Sally–ish legislators who force Harley riders to wear wimpy helmets.

One secret to NASCAR’s financial success: more advertising space to sell, including the entire surface area of Dale Earnhardt Jr. (Getty Images) |

The sport’s evil daddies are wickedly trying to cramp the fans’ old-school style. “NASCAR itself is trying to tone down some of its rural rebel imagery,” says Williams. It’s begun asking fans to take down all flags before a race, on the pretext that they block TV cameras’ views; in fact, says Wright, “The purpose is to get Confederate flags off national television.” Cameras pan away from fan T-shirts bearing such echt–NASCAR fan sentiments as “Fuck You, You Fucking Fuck.” Thanks to an FCC crackdown nobody seems to blame on Aunt Sally Ashcroft, NASCAR penalizes foulmouthed drivers like Johnny Sauter and Ron Hornaday. It sternly instructs others to quit punching each other in public.

“It’s the money,” says Dunshee. “When the big money moves in, and those big sponsors, it loses its little Dukes of Hazzard stuff.” What they’ve all got to remember is why NASCAR cars are outdoing NFL: “They’ve just got more advertising space,” says Dunshee. “The football player just doesn’t have the surface area that a car does.”

NASCAR ads fetch the most money by reaching out to a maximum audience. Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia Center for Politics, says NASCAR’s growth exemplifies a truism: “As a sport becomes more widely popular, inevitably it starts to look more like America.” Next year, nine out of the 36 NASCAR Nextel Cup races will be west of the Mississippi.

And now it’s the Nextel Cup, not the Winston Cup. The sport has ditched its traditional tobacco-money sponsor and hitched its dreams to the kind of high-tech star Seattleites revere. NASCAR, meet Nasdaq! Mediagenic boytoys are upstaging good old boys. NASCAR’s first legend (the subject of that 1965 Tom Wolfe essay, “The Last American Hero is Junior Johnson. Yes!“) was a Carolina bootlegger’s son discovered while plowing barefoot behind a mule; he won fame with the power-slide technique he’d used to elude revenuers (except that one time they ambushed him and threw him in jail). He wound up married to his high-school sweetheart on their own 42,000-chicken farm.

Flash forward to now: Jeff Gordon, a California-bred champ with a movie-star mug, got the seven-year itch, ditched his wife, the former Miss Winston beauty queen he met when she handed him a trophy, for Playboy‘s Miss October 2003, confusing the angrily traditionalist fans of the more unhandsomely manly Dale Earnhardt. (They protested his newfangled good looks with fag-bashing acronym signs: “Fans Against Gordon” and “Forget About Gordon.”) Forget about the farm: Gordon hosts SNL and sunbathes with topless top model Amanda Church on a St. Barts beach. From a Manhattan penthouse that probably saw as many chicks as Junior Johnson saw chickens, he’s foreseen NASCAR’s manifest destiny to expand throughout North America—though, in a policy that will please one North Seattle fan, he draws the line at Europe.

Down-home Johnson had ropes instead of seat belts, and fans would track his progress by the oval halo of smoke hovering over the track from his burning gumball tires, shouting (as Wolfe reports), “Great smokin’ blue gumballs god almighty dog! There goes Junior Johnson!” Today’s NASCAR fans track Gordon via in-car cameras and headphones tuned to his radio chatter with the pit crew. Ecstatic fans used to swarm the pits to peel the decals off the cars; now they pay top dollar for merchandise adorned with their idols’ numbers, logos, and corporate sponsors. Once dirt poor, racing has struck it filthy rich.

“It started in moonshine,” says Democratic state Sen. Tim Sheldon, the Economic Development Committee chairman, who recently visited Daytona to check out the chances for importing NASCAR culture, “but I didn’t see people spittin’ tobacco down there—it’s a pretty upscale crowd.” In fact, NASCAR fans are richer than the average American, earning about $51,000 a year. “It’s a crowd that isn’t any different than what you’d see at a Mariners or Seahawks game.” Indeed, several of the local fans I saw sported Mariners shirts and hats.

TRADING PAINT WITH BRITNEY

NASCAR is popping up all over mainstream American culture. Britney Spears has announced plans to co-star with racing greats in a NASCAR feature film by the screenwriter of that other saga of the historic meeting of alien civilizations, Contact, James V. Hart. She may also star in a remake of the car-culture classic The Dukes of Hazzard. (She’d be ideal for a movie spin-off of Mattel’s hit product NASCAR Barbie, too.) Will Ferrell could beat her out of the gate with his forthcoming racetrack opus, Talladega Nights. Racer Dale Earnhardt Jr. does videos with Sheryl Crow and 3 Doors Down.

Dubya hopes that his NASCAR Dads will kick some Soccer Mom tailpipes. (AFP / Getty Images ) |

Nor are highbrows immune to the spreading cultural contagion. The Roanoke (Va.) Ballet Theater scored a hit this spring by staging a NASCAR ballet, with the initially bewildered Mongolian National Ballet dancer Unur Gunaajav taking the role of the Pacer Car. It’s a natural: NASCAR really is our most popular form of modern dance—the pas de deux of the pass, the grace of the power slide, the multicar pileups like a corps de ballet of prettily crumpling metal with surprisingly few corpses inside. The terpsichorean technique is limited, alas: All NASCAR Nijinskys can do is turn left and crash.

On Forbes magazine’s list of the 10 top-earning dead celebrities, the only name not affiliated with Hollywood or the music business is Dale Earnhardt, who died on the last lap of the Daytona 500 in 2001 and grossed $15 million in 2003, threatening to overtake George Harrison ($16 million) and John Lennon ($19 million). Recently, the you-are-there film NASCAR 3D: The IMAX Experience was the top-grossing movie in the company’s history; its per-screen average actually beat the No. 1 movie, The Passion of the Christ.

And The Passion of the Christ star Jim Caviezel drove the pace car at the Indy 500, while Interstate Batteries chose to advertise its brand via a Passion of the Christ NASCAR car. Its chairman deems this a “double hit” for his product and his savior, “the vehicle for our salvation.” Gentlemen, start your engines and head for heaven!

At a deeper level, NASCAR is a marketing paradise of double hits, a fusion of humans and symbols, corporate brands and stars. In NASCAR slang, a car crash is called “trading paint.” That’s a good metaphor for the way images rub off on each other in the NASCAR drama. NASCAR VP Paul Brooks called the proposed Britney racing movie “the perfect blend of two incredible brands.” NASCAR Barbie wears the logos of NASCAR and a fellow Mattel toy, Hot Wheels. In reviewing the NASCAR IMAX film, an entertainment branding another entertainment, Entertainment Weekly‘s critic Lisa Schwarzbaum complained about feeling trapped in a hall of advertising mirrors. Narrator Kiefer Sutherland, she says, reports that, “of course,” NASCAR rigs are equipped with AOL for Broadband.

“Of course?” kvetches Schwarzbaum. “It’s not enough that America Online is an official NASCAR partner and that AOL is a corporate cousin of Warner Bros., which shares a producing credit for the movie with IMAX and the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing itself? Or that corporate cousin Turner Sports Interactive produces the official NASCAR Web site? Or that I, in my 3-D glasses, was taking notes for Entertainment Weekly, a division of corporate cousin Time Inc.?”

You might think fans would object to being manipulated by far-off corporate forces in New York—being branded, you might say—but really, they savor the sensation. They buy three times as much of sponsors’ products as non–NASCAR fans do; NFL watchers mute the sound during commercials, but for NASCAR fans, the commercial message is intrinsic to the entertainment. It furthers the illusion that they are at the center of the media swirl, in the driver’s seat, tattooed with emblems of corporate power, plunking pedal to the metal in the apotheosis of an average-Joe’s car. On the track, unlike in life, it’s a fair contest any man can win by skill and fearlessness. They’re proud that, unlike NFL or NBA fans, NASCAR fans are free (for a price, maybe) to mingle in the pits with the crews. Watching the pit crew swarm a car at a NASCAR race, Tom Wolfe writes that it’s “as if they are mechanical apparati merging with the machine as it rolls in.” It’s not just the machine of the race car today’s fan merges with, it’s the larger corporate entertainment machine in all its colorful hum and glory.

Crucially, the symbolism all boils down to one man they can identify with. Victory is a thrill, but defeat need not be agony. It brings your driver down to your level. When Jeff Gordon proved a loser on the racecourse of matrimony, Larry Woody of Auto Racing Digest found that fans who used to hate him started sympathizing: “One tattooed, barrel-chested fan scratched his beard, grinned, and opined: ‘I never thought me and Jeff Gordon would have anything in common, but as it turned out, we do. His ex–old lady took his mansion, and mine took my dam’ house trailer!”‘

A NATION OF ONES

Though it takes teamwork to keep a race car running, NASCAR fans don’t root for teams. It’s all about identifying with the heroic individual defying the laws of man and physics. The Intimidator’s fans rooted for him only, and hung rival Jeff Gordon in effigy on their RVs or placed a photo of his face inside a toilet seat mounted on the wall with the sign “Donations here.” The xenophobic hatred in NASCAR and the sense of aggrieved self-reliance are emotionally distinct from other sports. It’s a sport of outsiders who historically felt oppressed.

Wolfe traces its origins to the ethnically unmixed Scotch-Irish Carolina mountain settlers, isolated by geography and moonshiner’s paranoia: “There was a strong sense of family, clan, and honor. People would cut and shoot each other up over honor. And physical courage: They were almost like Turks in that way.” The core historic fandom of NASCAR is America’s equivalent of Islamist revolutionaries: rural, religious, resentful, poor, angry, fractious, tribal, responsive to a clever tyrant’s lies, inclined to volunteer as cannon fodder against alleged conspiracies against them.

Driver Jeff Gordon represents the new NASCAR: He hosts SNL and has a trophy girlfriend, Amanda Church. |

Nowadays, of course, NASCAR fans are much richer, and closer to the center of American culture. But one reason for that is that our national culture has become more like the isolated hillbilly culture that gave NASCAR birth. Everyone feels like a resentful outsider in Bush’s America, even Bush administration insiders who won’t talk with anyone outside the White House (nor anyone inside who dares to utter inconvenient truths).

Voters identify with Bush because he’s like a clannish, white-trash, pissed-off-outsider NASCAR driver: He won’t take the Lord’s name in vain, but he calls people “assholes” a lot, and when asked to explain a bald-faced lie, he responds with a look that, if it were a T-shirt, would say, “Fuck You, You Fucking Fuck.” He presides over a republic that looks more and more like Iraq, politically speaking: an uneasy, trustless coalition of warlike tribes—not a union anymore, no way, more like a New American Confederacy of demographic constituencies, red state, blue state, Soccer Moms, NASCAR Dads, Gordon fans, Earnhardt fans, gun nuts, gun banners, right-to-lifers, right-to-choosers, all of them demonizing each other like sniping Shiites, Sunnis, and insurgent Kurds. Bush and his extremist supporters control every branch of government and much of the media, and still they feel bitterly dealt out by society. They plunder the masses on behalf of the few, and yet they feel like they’re somehow the victims.

That victimized feeling resonates for more and more Americans. Maybe NASCAR is rising, not as a manifestation of the Old South, but a sign of the fraying patchwork of America. NASCAR nation is not a crowd but a large collection of nations of one, each against the other. The New Deal ideal was: We look out for each other, even the most unfortunate. The New American Confederacy says: We look out for each other, to blow each other away in a Social Darwinist Grand Theft Auto fantasy. It’s a Mad Max world—if you blow a tire, I’ll smash you into the wall, seize the prize money, and join the tribe inside the winner’s circle. I’ll trade paint with you so hard your head will bear my sponsor’s logo backward!

The Northwest NASCAR track could be fun, whichever county it winds up in. No doubt our local culture will change it in interesting ways: fresh crab cakes instead of stale Carolina corn dogs, anyone? Chateau Ste. Michelle champagne flutes instead of beer funnels? Or maybe things won’t change that much after all. “I don’t think it’s the red zone invading the blue zone,” says Dunshee. He thinks an ISC track would simply give thousands of current local fans now glued to the tube a place to congregate besides a NASCAR bar. He’s also suspicious about the putative cash bonanza we’re supposed to get. “The taxpayers end up footing a bill. There’s some economic growth, but there’s some cost to it. I don’t think we should roll over people—I think we should make sure it has the minimal negative impact. We can say, ‘Screw those people,’ but what if it was your neighborhood, what if it was your house that was bein’ impacted?”

Uh-oh! That sounds like antiquated New Deal thinking. Get with the program, Dunshee! Stop thinking about others as your fellow Americans! Get in that car and trade some paint. Because what NASCAR signifies is the decline of the idea that we’re all in this together. In a NASCAR world, we’re all in this alone.