The late winter sun

has begun to retreat behind the snow-speckled Bannock Mountain Range on the outskirts of Pocatello, Idaho. Frank Holden shields his eyes from the glare that floods his office, located in an industrial strip a mile east of the massive Simplot fertilizer factory, where cement silos cough up smoke into ice-blue skies.

As the rumble of another Union Pacific train bulging with coal sounds in the distance, Holden recounts a phone call he wishes he’d never received.

It was February 10, just after 7 p.m. Holden was at his home on the south side of town, where juniper trees and sagebrush dominate the surroundings.

And Gov. Jay Inslee was on the line.

“He said, ‘Here’s what I’m going to do . . . ’ He said something about the cost of the death penalty and all its flaws, and whatever. It didn’t last long, maybe five minutes, a courtesy call, I guess. He says, ‘I’m sorry for your daughter.’ Then he says he couldn’t imagine what it must have been like to go through this.

“And I told him, ‘I’m really disappointed. I’ve been waiting a long time for justice.’ ”

Almost 26 years, in fact.

“And after all that time, this governor walks in and says he knows better.” Holden goes on. “Talk about cruel and unusual punishment: having your daughter murdered, going through the trial, getting the conviction, getting the death penalty, and going through all the appeals.

“[Jonathan Lee] Gentry knew he was done. He knew justice was coming, and I think this governor knew that, that this was going to come across his desk this year.”

In June 1988, Cassie Holden had finished seventh grade at Franklin Middle School in Pocatello. She was four months shy of her 13th birthday and excited to take her first plane trip. On June 11, she flew by herself on a puddle-jumper to Boise and caught a small jet to Seattle. “She hadn’t seen her mother in six months,” Holden recalls.

On the morning of June 12, Cassie, now reunited with her mother in Bremerton, called home to tell her dad all was well. “It was an open-ended ticket. I told her she could stay as long as she wanted that summer. We made plans that she would call me every day.”

On June 13, which happened to be Holden’s first anniversary with his new wife, Diane, he got a call from Terry Holden, Cassie’s biological mother: “She said Cassie was missing.”

Cassie had gone for a walk near Bremerton’s Rolling Hills Golf Course, close to Terry’s house near the clubhouse, but failed to return for dinner. She was picking wildflowers.

On June 15, while a panicked Frank and Diane were driving west, Cassie’s body was found in a wooded area near the golf course.

On the Idaho-Oregon border, Holden received the news. “We pulled into a truck stop at Farewell Bend, and it was right up there on the TV screen,” Holden says, his voice cracking. “They had the news that Cassie was found, that she was dead. Then I called my father [in Pocatello] and he told me what had happened.”

The autopsy revealed that the girl, Holden’s only child, had been struck in the head with a blunt object eight to 15 times. A 2.2-pound rock, the murder weapon, was found at the crime scene, according to police reports. Some of Cassie’s clothing was partially removed, but the autopsy did not conclusively show any evidence of sexual assault.

At the time of the murder, Jonathan Lee Gentry, then 32, was free on bail, awaiting trial on a charge of first-degree rape.

Frank Holden is 59 years old, a ruggedly handsome man with steel blue eyes and a thick mane of hair, flecked with gray, that he brushes back. He’s lived his whole life here and can’t imagine going anywhere else. Holden has made a nice living for himself as the owner of SnugFleece, where he and his six employees make wool mattress covers and blankets. The company started in 1988, just a few months before Cassie’s murder.

An outdoorsman, Holden loves to fish and hunt, ride his mountain bike, or head up to Pebble Creek to hit the slopes of the Portneuf Range inside Caribou National Forest. “Cassie was a good little skier. She got that passion from me.”

Quietly, he continues. He wants to talk about her. Even now, he confides, when a stranger asks in passing conversation whether he has any children, “I always say, ‘Yes, I do, a daughter.’ ”

“She was an avid little reader and talked about having a large family. She wanted twins. I don’t know where she got that. She was a soccer player and rode horses. She wasn’t real outgoing, but she always stuck up for the underdog.

“And like I said, she loved to pick flowers. She was picking them for her mother that day to bring home to her when they were going to have dinner. They found a small bouquet near where she was killed.”

Holden had his daughter cremated in Port Orchard after the autopsy was completed, four days after his arrival. He brought her ashes back to Pocatello, put them in an urn, and placed it in her bedroom beside a picture of her. The urn and the picture remain there today.

The church was packed for Cassie’s memorial. “There were so many friends and family. There are still some people who stay in touch, grown women now, Teresa and Tamberlie, who knew Cassie,” Holden says. “I see them from time to time. People here don’t talk about this much anymore. It’s been a long time ago. People forget. They especially forget about the victims.”

Again, the tears flare. “You know, you never do recover. It’s always there. You’ll meet someone new, and if you get close to that person, it comes up. And you tell them, and then you feel bad when you tell them, because you know they’re feeling bad. The people who do get close to me say I got to let it go, but I can’t let it go.”

Jonathan Gentry was staying

at his brother’s house near the golf course. Witnesses told police that a man matching his description was on the same trail in that wooded area around the time Cassie was bludgeoned to death.

In August 1988, Kitsap County prosecutors, armed with a search warrant, went to Gentry’s residence and found the most incriminating evidence of all: a pair of shoes that had been recently cleaned, but with bloodstains on the laces.

Over defense counsel’s objections, hair and blood samples from Cassie’s body were subjected to several tests, including DNA tests. Meanwhile, Gentry was tried and convicted on the pending rape charge and transferred from Kitsap County Jail to prison in Shelton. An inmate at the jail named Brian Dyste would later testify at Gentry’s murder trial that Gentry told him at some point, “They found my hair on the bitch,” and that he’d admitted to killing the girl.

For the first time in Washington, DNA results were presented in a capital case, which made for complex and often tedious proceedings that dragged on for months.

On June 26, 1991, Gentry was convicted of first-degree murder. A week later, he was sentenced to death.

“I attended the trial—most of it, anyway,” remembers Holden. “I was advised not to be there for the gruesome testimony.”

Asked what it was like to see his child’s executioner each day at the Port Orchard courthouse, Holden replies evenly, “This is not a person. This is not even an animal. He’s less than an animal. I was told to have no eye contact, and I don’t think we ever did.”

After a long pause, Holden adds, “Yeah, there’s the thought of revenge. I thought about ways to kill him. You think about bringing in a gun. You think about a lot of ways to kill him.”

Holden did get some satisfaction after that bloody pair of shoelaces sent Gentry to death row. But never did he imagine the death sentence meted in the summer of ’91 would never materialize.

“They told me it would take five or six years with all the appeals, so you go through it, and you think someday you will put it behind you, but it’s not put behind you.”

“It was tough on the marriage,” Holden reveals later in our visit. “We discussed having another child, and I said I couldn’t—that I couldn’t go through it again. That I couldn’t go through losing another child. I mean, children are supposed to bury their parents, not the other way around. She was totally supportive of that.”

Frank and Diane divorced five years ago, after 22 years of marriage. “I don’t know where she is now,” he says. “I think she’s living in Boise. I don’t know for sure.”

Terry Holden, Cassie’s mother, died last month, around the time Washington’s Supreme Court rejected a petition for the release of Gentry, the state’s longest-serving death-row inmate. It was that rejection, which followed a series of spurned appeals, that virtually sealed Gentry’s fate, making him likely to be Washington’s first execution since Cal Coburn Brown died by lethal injection in September 2010.

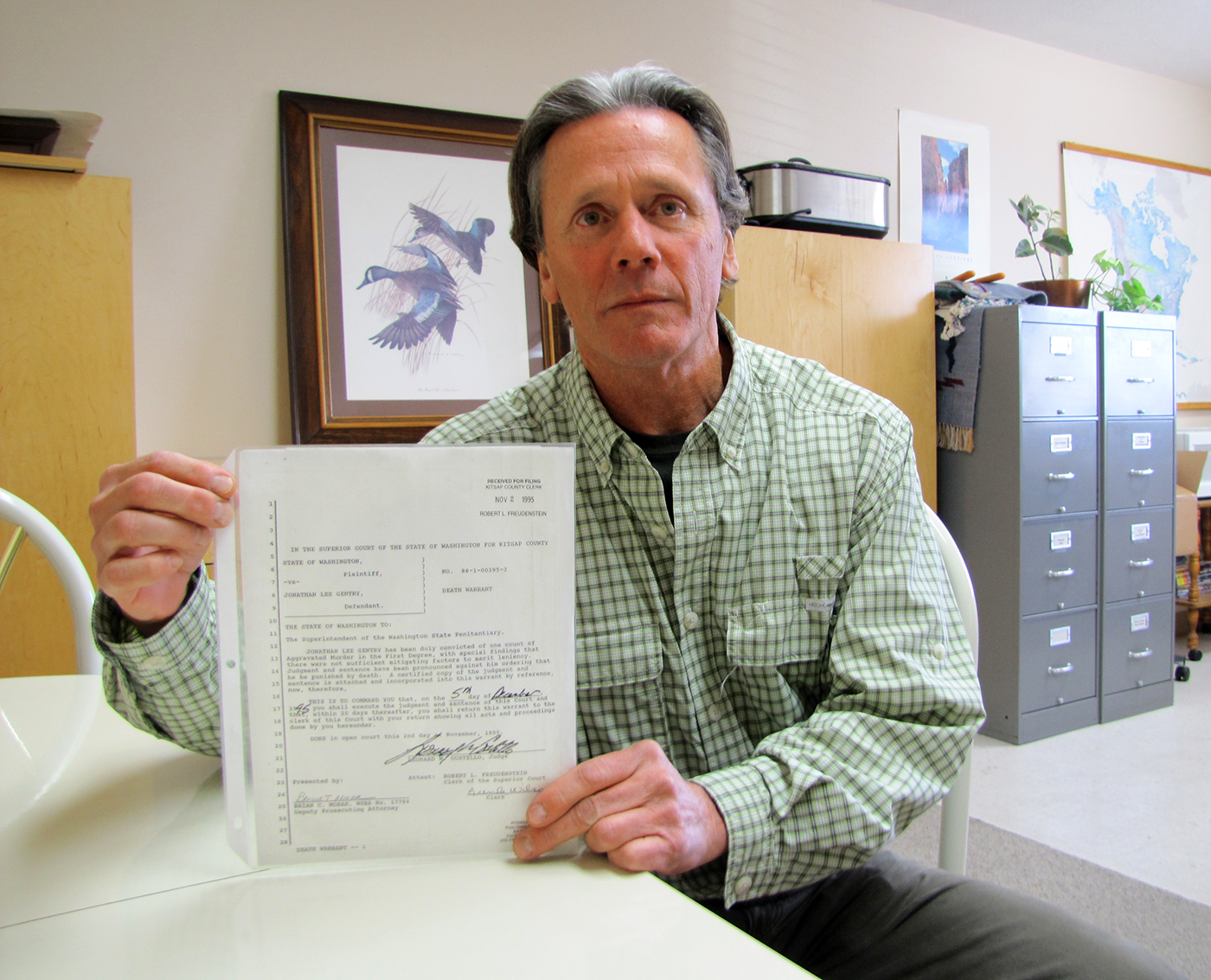

As darkness falls, Holden walks to his desk and collects a copy of the death warrant he keeps sheathed so many years later in a clear plastic cover. It is dated November 2, 1995, and signed by Judge Leonard Costello, setting the date of Gentry’s execution for December 5, 1995.

“I thought we were there, finally, and now with what your governor did, we may never be,” Holden says angrily. “This whole thing is something that may never end. And the thing is, there’s not a thing I can do about it. I am powerless.”

Cassie Holden would be 38 today.

“All I have now is memories,” Holden whispers. “She’ll always be my daughter.”

Jonathan Lee Gentry remains on death row in Walla Walla. He’ll die there, Inslee has made clear—though not by execution, as long as the current governor is in office.

econklin@seattleweekly.com

For the story behind Gov. Jay Inslee’s decision, read “Death Penalty, Interrupted,” here.