It’s an overcast May day on “Iron Mountain,” a sprawling 10-acre junkyard in rural unincorporated King County near Renton. A grey pitbull named Chiba—named after slang for black tar heroin—romps along the trash-littered dirt road that loops through the sea of aging trucks, buses, cars, boats, and piles of scrap metal, yard waste, and lumber while a smoke plume from a fire hidden behind some vehicles rises into the air. The scene is surreal and dystopian.

Charles Pillon, the 77-year-old ex-cop and owner of the property, is commanding an excavator to claw at a pile of yard waste and assorted junk. He doesn’t seem to hear me drive up or call his name over the snarls of the machine. “Do you know how to drive one of these?” he gruffly asks after I finally get his attention, a seemingly subtle dig at my presumably urban sensibilities. Despite his age, he’s still got a thick head of hair and a lampshade mustache which has only partially grayed. After we exchange pleasantries, he welcomes me to his property, describing it as “the Appalachia of the West.”

It’s easy to see why locals dubbed it Iron Mountain. He’s accumulated an astonishing number of vehicles and a quantity of debris—ranging from fire trucks and buses to piles of rusting paint containers and tires mixed with yard waste. The detritus consists of unwanted cars and waste people brought him to unload and items found via Pillon’s own scavenging off nearby roadways. Valuable metals would be salvaged by Pillon or the assortment of homeless people whom he’d let live on his property throughout the years, the unofficial tenants earning their keep in exchange for their contribution to his “recycling” operation, which entails crushing cars using Pillon’s hydraulic shovel and selling them to regional scrap metal buyers such as Seattle Iron.

We soon regroup at his two-story home at the center of the property—slightly cordoned off from the rest of the property by a thicket of large trees and a hedge, boasting a grass yard littered with lounging dinghies and small sail and power boats. He immediately returns to his notion that outsiders can’t understand what he’s doing on his property. “This is my art collection—although it needs refining. On the other hand, some people drive through here and say ‘Oh my god, Jesus Christ, this guy has to be in jail.’ ”

The rancor Pillon speaks of stems from a battle that he’s been locked in with various King County and state-level agencies for almost 20 years over the state of his property in May Valley. Pillon argues that the property serves a valuable role in the community, providing a place for people to bring their unwanted machinery and waste, while also offering a place for homeless people in the community to sleep. County and state officials see it as an illegal wrecking yard that doubles as an environmental catastrophe where toxic chemicals from the strewn machinery are leaching into the soil and nearby waterways and waste incineration pollutes the air.

Since the ’90s, county, state, and federal agencies have tried to bring Pillon to heel by levying over $120,000 in fines (only a fraction of which he has actually paid), placing several liens on his property, and even successfully prosecuting him for felony malicious mischief in 2007. None of these have done anything to deter him. As a 2014 King County Public Health environmental assessment report on Pillon’s property states: “Little to no activity has been taken by the owner to cease illegal operations or cleanup wastes brought onto the property.”

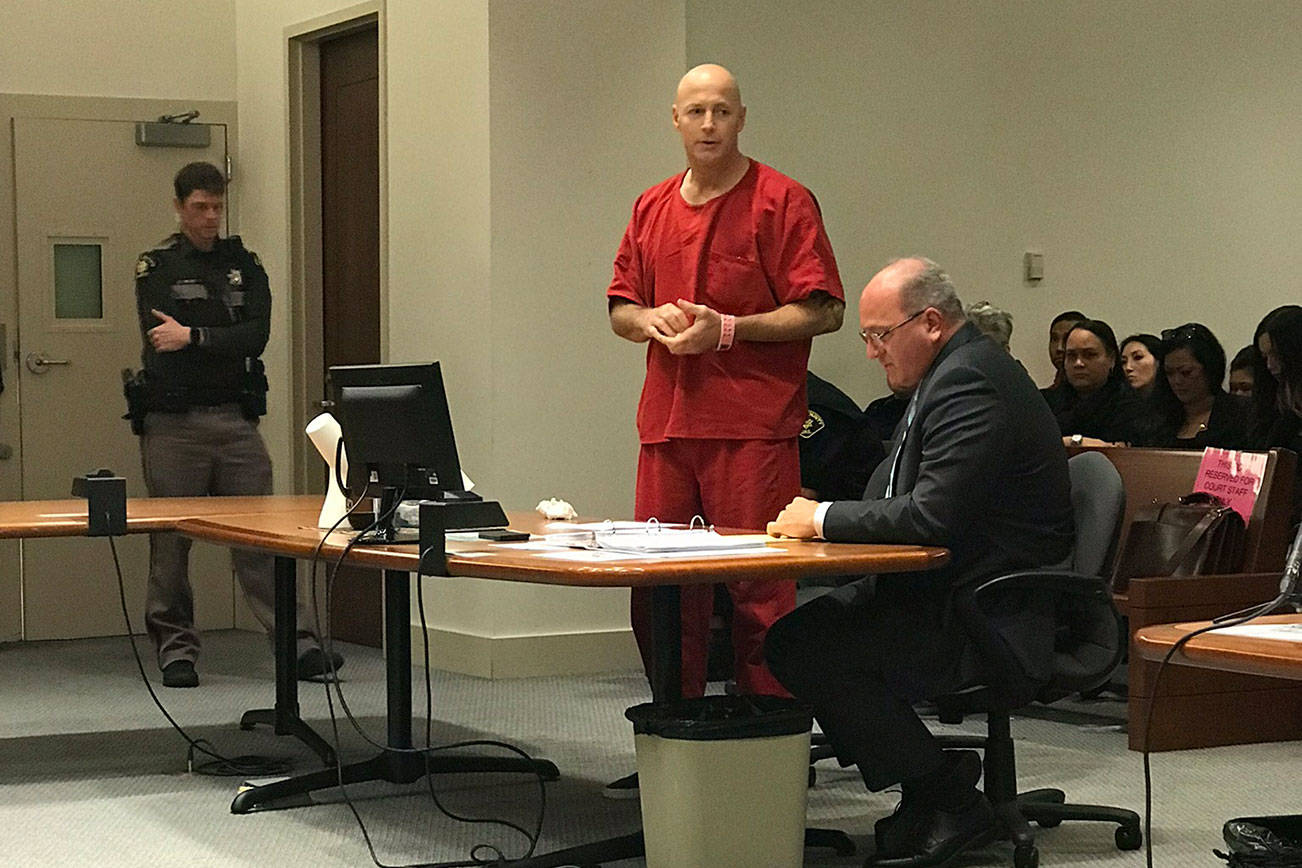

Then, in 2016, an inter-agency search raid was conducted at Pillon’s property—where inspectors allegedly found over 50 wrecked vehicles and 20 boats. The newly created environmental protection unit at state Attorney General Bob Ferguson’s office filed felony charges against him, slapping Charles with a violation of the state hazardous-waste laws, unlawful dumping of solid waste, and vehicle wrecking without a license (with a prior conviction). On April 19, a King County Superior Court judge upheld the charges, bringing Pillon’s standing felony count resulting from his rebellious activities on Iron Mountain to three. Sentencing for the 2016 case is scheduled for June 15, and Bill Sherman, Ferguson’s environmental unit chief, told Seattle Weekly that the state is seeking both financial penalties and jail time.

“Mr. Pillon continued to illegally dump solid waste and hazardous waste despite every effort by every agency that had contact with him over one decade, two decades, however long this problem has been going on,” Sherman says. “Were Mr. Pillon to recognize that what he’s doing is harmful, I think it would be easier to persuade him to stop. That’s where criminal prosecution comes in.”

Pillon is still characteristically defiant and seemingly ambivalent about the recent felony convictions, claiming that he’ll appeal them after sentencing. “They convicted me and I don’t care. There is purpose in what I’ve done over 30 years up here and they don’t negate that.”

“The only fact that troubles me about the felony conviction is that once again I’ll have to surrender my firearms,” he added. Pillon says he owns around 20 guns.

But, despite his continued tough talk, Pillon is also signaling that he’s willing to give in a little after slugging it out with the county for decades. He talks of getting past the recent convictions and cleaning up the property so that he can finally appease his significant other, Linda, 58, who has long harbored reservations about the state of Iron Mountain. He wants to travel to some of his old haunts in his hometown of Wapato near Yakima, and perhaps even sell the property to developers eager for a pocket of rapidly growing King County.

Washington State Trooper Troy Giddings, a longtime Pillon adversary, says that he doesn’t buy it that Charles can be tamed. “I’m not confident of that,” he says. “He’s fairly set in his ways.”

For much of his adult life Pillon has been fiercely stubborn in his beliefs about the incompetence and routine overreach of government bureaucrats. He sees his own do-it-yourself approach as serving the public good—regardless of any rules or laws. Back in 1995, when the county was fining him $100 a day for roughly six months for illegally grading his own property, he told The Seattle Times: “If the county wants a war with Charlie Pillon, they’ve got a war with Charlie Pillon.”

“There’s an enormous overburden of regulation in this country. By now it’s legendary,” says Pillon. “Somebody’s got to fight these battles. So I do it. I take them head on. They beat me up a little bit, as they will now, but they don’t discourage me.” While he doesn’t consider himself a “blind libertarian,” he believes in “healthy government” and holds a “live-and-let-live mentality.”

Years earlier, he was fired from the Seattle Police Department in 1987 for walking off the job in an act of defiance after being transferred to an office job in the department’s communications office. He says the transfer was retaliation for his routine public criticism of SPD’s narcotics policing strategy and his habit of regularly entering drug houses in Seattle’s Central District and the Rainier Valley without warrants and developing relationships with users and tenants (during which he’d also seize drugs, guns, and stolen property). Of his decision to walk out on the job rather than do his duties in the SPD communications department, Pillon says, “I sure as hell wasn’t going to go sit like a monkey in a cage for them to illustrate that they’d shut this rambunctious cop down.”

Reflecting on his days at SPD as a patrol sergeant at his kitchen table in his two story house—which he and his family and friends built from the ground up after he first bought the property in 1977— Pillon sees a common thread between his actions with the police department and his current wars with the county. “The same impatience that drives me to defy these people now. I was a defiant Seattle police member, but in a constructive way … That probably poisoned my mind a little bit, the well in my spirit, ‘Hey, if you can make it work and it’s right, just do it.’ There will always be detractors.’”

Renton Mayor Denis Law told Seattle Weekly in a phone interview that Pillon, while maybe less than pragmatic, is always well-intentioned. “He’s somebody that has very strong convictions of what he feels is right and needs to be done. He gets very frustrated with political process and the lack of accountability for getting things done. So consequently, he’ll do things on his own to try and achieve a positive outcome.”

Law, a former freelance reporter who used to frequently cover Pillon’s activities, remembers his SPD days, when Pillon butted heads with the police brass over his unsanctioned police work, which he alleged produced better results than the department’s standard practice of simply locking up low-level drug offenders.

“Often times what Chuck would do is he would go and knock on the door and start talking with individuals who were renting the house and say, ‘Look, you guys are creating problems for the neighborhood,’” Law says. “Some people including his precinct commander, completely supported [Pillon’s work], while at the same time downtown and some of the narcotics division just thought he was a loose cannon trying to gain notoriety.” Pillon himself certainly doesn’t shy away from describing himself and the officers who endorsed his unconventional policing tactics as “mavericks.”

Pillon has long displayed a tendency to act in the name of the perceived public benefit regardless of the consequences or sanctioning. In the early ’90s, Pillon rebuilt a notorious intersection along Highway 900 that experienced frequent car accidents. In 2001, he dredged a portion of the May Valley Creek with a backhoe due to flooding issues (which earned him a $25,000 fine for violating local grading laws). In 2006, Pillon again was taken to task by the county for removing logs, woody debris, and roots from the Cedar River previously installed to cultivate salmon habitat because he was concerned that the materials posed a threat to children swimming in the river and bridges. The episode eventually earned him a felony charge of first-degree malicious mischief. But for Pillon, the episode is a point of pride. “The rivers of this county are safer because of what I did,” he says.

In fighting the 2016 charges, Pillon submitted a statement by then-King County Deputy Ombudsman David W. Spohr declaring that Pillon “tirelessly” kept issues of river safety on the county’s “front burner” and that his complaints were “always in good faith.”

But not everyone sees Pillon in such a positive light, particularly when it comes to his property. The county has receives regular complaints from his neighbors about Iron Mountain being an eyesore and environmental hazard—often submitted anonymously for fear of retribution.

“Every few years there would be flare-ups of complaints from neighbors,” says Sue Hamilton, a health and environmental investigator with King County’s hazardous-waste division. Hamilton also used to coordinate the Interagency Compliance Team‚ a regular meeting between local, state, and federal agencies on major environmental hazards in the region that frequently tried to address the Pillon case.

“There is a contingent up there that views him as a neighborhood hero because they can take all their garbage there. It is a lot easier to take all their waste there because it is a lot cheaper,” she says. “Then you also have the neighbors who have to see it and have to be concerned about their water and stuff leaching off that property … one time there was a fire and one time somebody saw a [oily] sheen on the storm water.”

“Most of the complaints that we had gotten were about the smell coming off the property, contaminated water coming off the property; some of it was it was expanding beyond his borders,” says Sheryl Lux, a product line manager with King County Code Enforcement.

The complaints associated with Iron Mountain prompted routine visits and inspections by county officials, resulting in findings that substantiated the environmental concerns. In 2002, the Water, Land, and Resources Division of the county’s Department of Natural Resources and Parks collected samples of storm water leaving Pillon’s property that tested positive for high levels of fecal coliform—a bacteria that may indicate the presence of waterborne diseases—while lead and petroleum were detected in surface water on his property. The Puget Sound Clean Air Agency logged an asbestos release in 2006. Eastside Fire and Rescue has been called in frequently to deal with outdoor fires and waste incineration. During a 2006 inspection, the state Department of Ecology found during “multiple uncontained oil releases” into the environment. On certain potions of his property, the piles of waste mixed with soil and vegetation are estimated to be 20 feet deep, per the 2014 King County Public Health environmental assessment report. And during the interagency raid in 2016 , EPA staff took soil samples on his property, which tested positive for arsenic and lead.

“It’s not like agencies didn’t try to do enforcement, they did,” says Hamilton. “But it was to no avail because if somebody just ignores everything, they just ignore everything.”

According to both Lux with county Code Enforcement and Hamilton, part of the problem is that none of the agencies had the financial resources to do the clean-up themselves.

Pillon, for his part, has long contested the notion that his activities are environmentally harmful. “I know it’s not polluted,” he says matter-of-factly at one point. During my visits to the property he’d frequently direct my attention to the lack of odor on his property. “I have an utterly secluded piece of private property. It does not stink, it does not—despite the conviction—foul the waters of the state or anything else,” he says. “[The county] never shut the water off, intercepted it, put up a gate themselves, abated this place, which is quiet testimony to the fact that they know that the real impact is really pretty marginal and there are some positive aspects, keeping the trash off the streets for instance.”

Pillon has never seen his activities as anything other than a personal hobby.(He lives off the “best goddamn pension in the world” from the Seattle Police Department.) He calls his property his “sandbox.” “The exploration of trash that I recycle is clouded completely by the messy appearance that you see,” he says on the west side of the property near a pile of decaying mattresses. “It is so easy for the bureaucrats to just condemn the hell out of me.”

He’s got some rather imaginative and ambitious ideas for his vast array of discarded cars. “My ambition at a point in time was to create an outdoor industrial museum. I was going to go to the retirement halls—I even had a bus or two, I still have some buses—and pick up the old folks and bring them out for picnics and whatnot.” Another thought was to use piles of lumber to build bus stops for school children, or to plant flowers in some of the discarded boats.

Pillon’s unconventional arrangement with the handful of homeless individuals that he has let live on his property over the years was another aspect of his property simultaneously condemned by the county and propped up by the man himself. He has let homeless people stay in trailers and buses on his property in exchange for their help moving waste around the property or stripping down junk vehicles for scrap metal. “Only a few of them were that industrious. Most of them were just lay abouts,” he says. “I can always tell that hungry look in their eyes when they show up with one of the guys that either stayed here or still is. ”

He has been lax on drug use on his property, so long nobody causes a ruckus. “They know there ain’t going to be any bullshit up here. That’s not to say there was never any dope or anything because they’re addicts. But they knew damn good and well that they weren’t going to distribute and they weren’t going to have parties up here or hangouts,” he says.

But things still got a little wild from time to time. Pillon remembered a time when one man, “Dougie,” drove him up the wall because he “felt he owned Iron Mountain.” As Pillon tells it, he consequently took a excavator to an RV that he’d let Dougie had been staying in (Dougie wasn’t in the RV at the time).

But, according to Pillon, he’s been slowly booting the remaining homeless people off his property to get the county off his back (he says he was hit with a $12,000 fine by the county years back for having homeless people in substandard housing).

What comes next for Pillon and Iron Mountain is still unclear. After the June 15 sentencing, Pillon could spend time in prison—each of the two felony charges carries a five-year maximum sentence, and the AG’s office plans to seek jail time. It’s also unknnown which of the various involved agencies will spearhead the environmental clean-up, who will pay for it, or how long it will take. “The hard work on that will begin after sentencing,” says Sherman. “What Mr. Pillon did is not going to be easy to fix.”

Pillon himself has taken a somewhat conciliatory stance. In addition to kicking out the homeless population, he’s put up signs in his driveway that say “no dumping” and even met with real-estate agents to investigate a potential sale of Iron Mountain.

Joseph Fanelli, a real- estate broker with Fortuna LLC who visited Pillon in early May to take pictures of the property, says that the 10 acres could probably sell for around $800,000 if cleaned up. “It doesn’t seem like an impossible challenge to make money, but it definitely would take some effort,” he told Seattle Weekly.

Linda, Pillon’s significant other, wrote in an email that she thinks he’ll comply with the courts and the county at long last. She’d also always hoped that he’d sell the parcel. “Chuck knows that I have never liked his home business … And how many boats and old cars does a person need, really?”

Pillon is quick to get pensive these days. “The value that’s built here and the way that I’ve been true to myself, I guess, standing my ground on these things, that will go just as comfortably to the grave with me as would another,” he muses at his kitchen table. “There’s that saying that your character is your fate. When you get as old as I am, you can see your life in such context. You can look back on things that were truly stupid, but they were also truly inevitable. You can’t fight with who you are. Change either comes along on its own or it doesn’t.”

Update (June 15): On Friday, June 15, the King County Superior Court judge sentenced Pillon to 30 days in jail and a $15,000 fine. He was also mandated to comply with assisting authorities’ efforts to clean up the environmental hazardous on his property. A future court hearing will determine what Pillon may have to pay to help fund the clean up in addition to the fine.

Correction (June 14): The state Attorney General’s Office plans to seek a yet-t0-be-specified jail sentence for Pillon, not the maximum five years as was previously stated in the original article.