Some years ago, my then-grade-school-aged daughter was trying to figure out where our family fit in the grand scheme of things. “Dad, are we rich?” she asked. No, I answered. “Are we poor?” No. Her face brightened, and she said happily, “Then we’re the ‘just right’ people!”

That’s social-class theory according to Goldilocks. In my daughter’s eyes, we had attained a kind of secure just-rightness that offers comfort. That kind of value used to personify Seattle, a city that prided itself as being a middle-class, democratic, populist alternative to big Eastern metropolises or sprawling Western ones.

Rich people showed up in Seattle pretty late. The first millionaires were made by the Alaskan Gold Rush, which ushered in a rum, retail, and real-estate boom. Early labor activism added resistance to the growing influence of the robber barons, and the clash between upper and lower classes evolved a city in which there was little economic difference between union blue-collar workers and Boeing white collars.

Mid-20th-century, urban fantasists imagined that the 21st century would spawn cities of great equality—Democracity was one name given to this utopian vision. Seattle, tucked away and doing its own thing in the far corner of America, achieved something a bit like that: a middle-class idyll that embodied the American dream without being a soulless suburb or an economically stratified big city. Was it perfect? Far from it. But there were few rich people, few poor people, and a broad mainstream in between.

But times have changed. In response to my column on race last week (see Mossback, “Trouble in Vanilla City,” May 3), Beacon Hill/Rainier Valley resident Lewis Stockill wrote and described his family of three as “lower to mid middle class” with a household income of under $78,000 per year (see Letters, p. 5). That assertion seems astonishing. That much income ought to signal affluence. But then, Mossback’s real-estate agent recently sent listings that included a $750,000 bungalow in Fremont. Uff da!

The pressure on the middle class isn’t just local. George W. Bush’s plummet in the polls comes in part because the middle class is being crushed. Under Bush, middle- income wage earners are bearing the brunt of the tax burden, while the wealthiest Americans get the benefits of tax cuts. If the Bush tax cuts are renewed, by 2009, an estimated 72 percent of the benefits of extending the current tax cuts would flow to households making more than $200,000 per year. Nearly half would go to people earning more than $1 million. More and more middle-income wage earners don’t have health insurance. In 2005, 41 percent of Americans earning between $20,000 and $40,000 per year were uninsured. And the disparities between the rich and everyone else are widening dramatically. The liberal Institute for Policy Studies reports the income gap between average wage earners in this country and CEOs was a 42-to-1 ratio in 1980; the current gap is 431-to-1, or $11.8 million to $27,460. So much for letting the spoils trickle down.

Maintaining the middle-class idyll is becoming impossible not as a matter of happenstance but as a matter of policy.

That includes urban policy that promotes dense development in the name of sustainability. This is driving the cost of city living to impossible heights—more so in a city like Seattle that is focused on creating high-wage jobs. If you’re employed in high-tech, biotech, or other professional sectors, you might be making out OK. But the majority of folks don’t have those kinds of jobs or incomes. They are getting shoved out, bought out, or priced out—at least those who haven’t already fled to the exurbs.

Let’s go back to the bungalow for a minute.

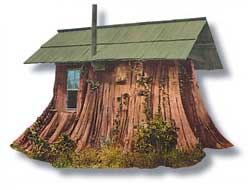

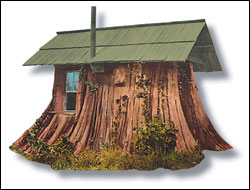

The bungalow appeared in the late 19th century as a modern, populist, low-cost alternative to the Victorian megahouses of that era. People of modest means could buy a sensible, one-story, single-family house designed for a small lot and to integrate well with the natural environment. They were easy to build and maintain, and had modern innovations like built-in bookshelves. You could order one from the Sears catalog for $900.

They’ve long been Seattle’s bread-and-butter homes. But rising land prices are changing all that. An article by Christine Palmer in Historic Seattle’s online magazine (www.historicseattle.org) describes the national trend of “bash and build” development, the accelerated destruction of existing small homes and businesses in cities. When the land price exceeds the price of the structure, you’ve got a tear-down—homes are either remodeled to maximize the value or they’re “scraped” off the land and replaced. You see the results all over Seattle as vacant lots and yards disappear and megahouses rise. In Madison Park, you see one-story bungalows raised into three-story bungvillas—mini-skinny towers in search of a lake view. John Chaney, executive director of Historic Seattle, which is dedicated to preserving the city’s architectural heritage, describes Seattle’s bungalows as “endangered.”

If bungalows are the new spotted owl of the urban ecosystem, their disappearance, or transformation into housing for the well-off, is a sign of larger problems. To me, preserving local culture and history is the least of it. The disappearance of the bungalow is an indicator of socioeconomic trouble ahead that poses a threat to Seattle’s “just right” people.