Bobette Riner publishes an electricity index used to promote renewable energy, and she bought a brand-new Prius last year to shoot the bird at the oil companies.

“I felt so smug for a while,” she says. “Especially being in Houston.”

She had been lucky to score the car from a dealership on Houston’s south side, because for nearly a year there had been a three-month wait to get a Prius. The dealership couldn’t even keep a model for the showroom.

The car had a “cute little body” that Riner loved, and she reveled in driving like a “nerdy Prius owner,” watching the energy-usage display on the car’s center console, trying to drain every possible mile from a gallon of gasoline. When she hit 2,000 miles, she could count her trips to a gas station on one hand.

On a rainy night last fall, a couple of months after Riner bought her Prius, she was driving toward the Houston Galleria for a sales meeting. She hated driving in the rain because a car wreck in college catapulted her through the windshield, and doctors almost had to amputate her leg.

Traffic near the mall was congested but moving, and Riner kept the Prius pegged at 60 mph, constantly looking at the console to manage her fuel consumption.

Suddenly she felt the car hydroplaning out of control, and when she glanced at the speedometer she realized the car had shot up to 84 mph. Riner wasn’t hydroplaning; quite simply, her Prius had accelerated on its own.

She pushed on the brakes but they were dead. Then just as suddenly as the car had taken off, it shut down. The console lit up with warning lights, leaving Riner fighting a stiff steering wheel as she coasted across four lanes of traffic and down an exit ramp.

The car stopped near a PetSmart parking lot, and Riner sat in disbelief, listening to fat raindrops pelt the Prius, wondering if her new car had actually gone crazy.

The Prius is one of the great success stories of the past decade, becoming the one car synonymous with “hybrid” and helping Toyota drill into a skeptical American auto market while the Big Three failed and failed again to produce efficient vehicles. But from day one, it has come in for criticism as well. Early reports claimed that the manufacturing is so complex and uses so much energy that the Prius stomps out a troublingly deep carbon footprint.

Now another side of the Prius has orbited into view, as owners share horror stories on blogs and message boards about crashing their cars through forests, garage doors, and gas stations.

Take Lupe Egusquiza from Tustin, California. She was waiting in a line of cars in September 2007 to pick up her daughter from school when her Prius suddenly took off and crashed into the school’s brick wall. Egusquiza reported $14,000 worth of damage to her car.

Or Stacey Josefowicz in Anthem, Arizona, who bought her new Prius in May 2007. A couple of months later, driving down a four-lane highway toward a stoplight, she stepped on the brakes but nothing happened. She freaked, then weaved into a turning lane, coasting to a Target parking lot with the brake pedal jammed to the floor. A Toyota technician told her she ran out of gas, but she objected that that wasn’t true; there was fuel in the car. Still, he returned her Prius to her with no repairs.

A month later, she sped through a stop sign when the brakes went out again. “I think they thought, ‘She’s a woman driver, she obviously let the car run out of gas,'” Josefowicz says. “Thank God I didn’t get killed or cause an accident; it would have been on their head.”

Or Herbert Kuehn from Battle Creek, Michigan. In October 2005, his Prius sped out of control on a highway before he “labored” the car to a stop on the gravel shoulder of the road. He was so scared of his Prius that he stopped driving it, but “under good conscience did not feel that I could sell it.”

Jaded Prius owners say there’s no resolution with Toyota—through their hometown dealer or corporate arbitration—and the company hasn’t lost or settled a single lawsuit concerning “unintended acceleration.”

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has two Prius investigations in its database from 2004 and 2005, but those involved the car’s cooling system. During a recall of floor mats used in other Toyota models, Prius owners were simply cautioned to make sure their floor mats were properly installed. [NOTE: This paragraph has been corrected since the story was first posted. The story originally said that Toyota had recalled faulty floor mats in the Prius.] Another explanation from Toyota is simple driver error.

“You get these customers that say, ‘I stood on the brake with all my might and the car just kept on accelerating.’ They’re not stepping on the brake,” says Toyota corporate spokesman Bill Kwong. “People are so under stress right now, people have so much on their minds. With pagers and cell phones and IM, people are just so busy with kids and family and boyfriends and girlfriends. So you’re driving along and the next thing you know you’re two miles down the road and you don’t remember driving, because you’re thinking about something else.”

Most owners, like Riner, deny they were mistaken about where the brake pedal is. At the same time, most aren’t looking to sue; they say they just want an explanation and a fair deal.

As Ted James from Eagle, Colorado, puts it (his Prius ended up in a river), “We’re not the kind of people to go through a lawsuit, and it’s not in our nature. Our concern was that no one else got hurt, that Toyota own up to its problem.”

From 2000, when the Prius was introduced in the U.S., through last year, about 1.3 million hybrids sold in the country, according to numbers from the U.S. Department of Energy; Priuses accounted for more than half those sales. But if things had gone as planned, American carmakers could have been dominating the hybrid market.

In 1993, the Clinton administration developed the Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles, awarding federal funds to Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors and giving them access to federal research agencies. The goal was to develop a car that got more than three times the gas mileage of full-sized vehicles already on the road.

Toyota was left out of the New Generation program, but it responded in 1994 by officially starting Project G21, a program to develop an environmentally friendly car. Three years later, the first Prius was released in Japan.

Chrysler, Ford, and GM still hadn’t shown any New Generation prototypes by the end of the decade, but an unveiling was scheduled for January 2000 at Detroit’s North American International Auto Show.

Heralded in newspaper accounts as a possible breakthrough, some of the designs certainly were radical, but, as it turns out, actually were just for dreamers. Each company rolled out a New Generation car, but after the show the prototypes disappeared from public view.

The federal government had already fed more than $1 billion to the three automakers—at a time when the American manufacturers were still highly profitable—with few results. The New Generation program was a failure at best; Ralph Nader called it “corporate welfare at its worst.”

The project was killed by the Bush administration in 2002.

Meanwhile, Toyota was priming the U.S. market for the Prius, led by David Hermance, now known as the Father of the American Prius.

Hermance, who lived in Gardena, California, worked as the top hybrid engineer at Toyota when the car was released in the U.S. in 2000, and while he didn’t have a hand in designing the first-generation Prius—it was strictly Japanese engineering—he furiously promoted and explained the car’s technology to the media and legislators.

In a 2004 interview with the Web site www.hybridcars.com, Hermance said his involvement with the Prius was an environmental mission for him, even if it wasn’t for “the mainstream marketing folks.”

“I’m convinced that global warming is real, and that if we’re not principally responsible, we’re at least contributing to that,” he told the interviewer. “I’d like to leave the planet a little better than I found it.”

The second-generation Prius, the model in production today, was directly engineered by Hermance, and he focused on making the car fun and peppy; his designs and marketing are credited with breaking the car into the mainstream. The new Prius was released in 2004, winning the Motor Trend Car of the Year award and a heap of other accolades.

A year later, Toyota sold 100,000 Priuses for the first time, and sales more than doubled each of the first two years the second generation was built.

“He was just a brilliant engineer and was really for the hybrid. He educated a lot of people,” Kwong says.

Hermance died in the fall of 2006 when he crashed his airplane into the Pacific Ocean.

Celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio and Cameron Diaz drove the Prius from the beginning, but in 2003 Toyota hired a public-relations firm to “bring Hollywood stars and Prius cars together [at the Oscars], replacing the gas-guzzling stretch limo as the ride of choice for eco-aware celebrities,” according to a Prius newsletter. Diaz, Harrison Ford, Calista Flockhart, Susan Sarandon, and Tim Robbins arrived in chauffeured Priuses.

Celebrities drove other hybrids, too, but the Prius had the advantage of being ugly.

“People were buying hybrids as a fashion statement. What’s the good of driving something you paid extra for, because you think you’re saving the universe, and nobody knows it?” says Art Spinella, co-founder and president of CNW Marketing Research, headquartered in Bandon, Oregon. “One of the things we found with the Honda Accord hybrid—they stopped producing it—was that people complained because it wasn’t visible enough.”

In 2007, The New York Times published data from a CNW report that said almost 60 percent of Prius owners bought the car because it “makes a statement about me.” For its other hybrids, Toyota made the “Hybrid Synergy Drive” badges on the outside of the cars 25 percent bigger, hoping to cash in on the Prius effect.

“The Prius is kind of a gimmicky car. Toyota originally designed it for young geeks in Tokyo: gadget-crazy young guys,” says Jim Hood, a writer who worked for the Associated Press for 15 years and covered the automotive industry for part of that time. “Then the crazy Americans fell for it.”

Gas mileage is another big draw for the Prius, and “hypermilers” take that to the extreme. Dan Bryant, a computer engineer in Houston, is a self-admitted Prian—a name fanatic Prius owners affectionately call themselves. He’s turned driving his car into a full-time hobby. He installed aftermarket gauges and an engine kill-switch—ordered from Japan—that makes driving seem like playing a video game, Bryant says, with the goal of getting the most mileage from a tank of fuel.

He’s constantly shifting the car into neutral, switching off the engine, and looking at his gauges to track things like pressure on the gas pedal and engine temperature, both of which affect gas mileage. Bryant coasts into stops without brakes when he can. He usually averages about 60 to 70 miles per gallon, but he got 91 out of his best tank and took a picture to prove it.

“When you’re only buying 40 gallons of gas [a month], $2 a gallon or $5 a gallon is basically the difference between eating out a couple nights,” Bryant says. “The biggest thing about it was that we didn’t really notice it.”

Many auto reviewers have also raved about the Prius. In 2008, the car ranked second in overall quality in a survey by J.D. Power and Associates, and it won the IntelliChoice Best in Overall Value award in its class.

Pete Bednar, the fleet and communications manager for the city of Bellevue, says the Prius is “one of the lowest-maintenance vehicles we have.” The city owns seven of the cars, and Bednar says they’re a good fit for white-collar staff, though not as useful for building inspectors and others who need to haul a lot of gear and climb in and out of the vehicle all day. (For them, the city has opted for the Ford Escape hybrid.) “I deal with fleet managers around the state, and we have not seen a lot of issues with Priuses,” says Bednar. “They’ve held up really well.”

Several Seattle-area mechanics also described the car as “great.”

Ted James was a believer, not only in the Prius but also in Toyota.

About the time the Prius was released in America, James, a middle-school math teacher from Eagle, Colorado, received a $10,000 Toyota Time grant, awarded to 35 math teachers around the country to develop inventive programs. James used his money to buy equipment to monitor local water quality, and his students used math to analyze the data.

In 2002, Toyota paid for James, along with the other Time winners, to travel to company headquarters in Torrance, California, and talk about their projects. One day during a lunch break, Toyota executives introduced the group to the Prius. Each teacher was outfitted with one of the hybrids for a day of driving around Torrance.

“I thought they were the coolest thing ever,” James says. He and his wife Elizabeth, who teaches at an elementary school, bought their first Prius three years later.

“I was very proud because we were the first teachers in the parking lot to be sporting a Prius,” he says.

On August 10, 2006, Elizabeth was driving the car east on Interstate 70 toward Denver to catch an early-morning flight. Near the small town of Lawson, she pressed the brakes to slow down, and when she let off the pedal, the Prius took off. The car wouldn’t slow down “no matter how hard I pressed on the brake,” so Elizabeth used her left foot to slam down the emergency brake. Nothing.

The brakes spewed blue smoke from the back of the car, and when Elizabeth glanced down, the speedometer read 90 mph and the Prius was rocketing toward a car in the slow lane. Gripping the steering wheel with both hands, she whipped the car around along the shoulder of the interstate, exited the Lawson ramp, ran a stop sign, passed a couple of people walking in the road, and steered into a grassy field when the feeder cut to the left.

“She said she felt like the pilot of a plane that was trying to crash-land,” Ted says. “So she was looking for a place to crash the car, and that was one of the things that were really tough: She thought she was going to die and had enough time to think about it.”

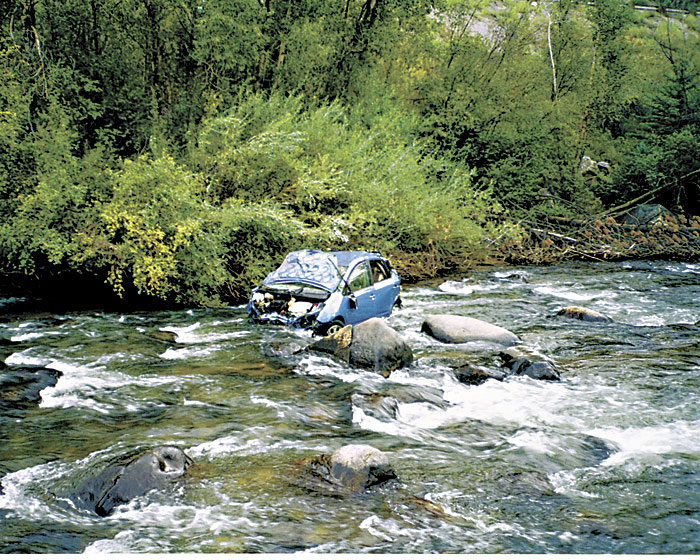

The Prius sped through a wooded area, clipped a weather monitoring shed, flipped, and landed in a river.

Elizabeth survived the wreck, but her legs and back were banged up and she’s still hobbled, despite a year of physical therapy. Scar tissue on her intestines requires her to drink MiraLAX for the rest of her life to ease stomach pains.

After the crash, Ted enlisted the help of a childhood friend, attorney Kent Spangler (who practiced family law at the time and now is a magistrate in Fort Collins, Colorado), to steer the Jameses through arbitration with Toyota. They wanted Elizabeth’s medical bills—about $15,000—paid, and to have the smashed Prius examined for a cause of the wreck.

“You’d think Toyota would be interested in how their car functioned in that crash,” Ted says. “My wife’s brother and sister owned Priuses, and we were really worried that this could happen to someone else. Toyota’s whole reaction was really disconcerting. It was like, deny everything.”

Toyota’s response was in fact minimal. In a letter to Ted, the company blamed the problem on excessive brake wear, stating “We are sure she believes that her vehicle accelerated on its own; but our inspection of her vehicle did not reveal any evidence to support her allegations.”

Bobette Riner’s experience wasn’t much better. When her Prius died in front of the parking lot, she composed herself and started the car again because she desperately needed to make her sales meeting. The Prius sputtered along for about a quarter-mile before shutting down again “at a spot where people coming from the Galleria couldn’t totally plow into me.” The Toyota dealership where she’d bought the car sent a tow truck and the driver took Riner to her meeting.

“I ended up being an hour and 20 minutes late, and only one guy stuck around, so I missed that opportunity,” Riner says.

The next day she went to the dealership to find out what had happened with her car, and the technician told her, “We know what’s wrong with it; you were out of gas.”

Riner was shocked because she was certain her gas tank wasn’t close to empty, and she wasn’t concerned that the Prius had shut down; it was the sudden jolt of speed that scared her.

“That was more than being out of gas,” Riner says. “How do you explain it suddenly being 84 mph?”

Stories from other Prius owners involving unintended acceleration are fairly common, and one of the first places to publish them was the Web site www.consumeraffairs.com, which each day collects about 400 complaints that are read by editors and stored in an online database.

“One of the trends we started to see was that there were odd things going on with the Prius, not only with the acceleration but with loss of traction on slippery surfaces,” says Hood, the former Associated Press writer who now owns the Web site. “The Prius was something a little different when it came out, so we paid a little more attention to it than if it was a brand-new pickup or something.”

The site’s automotive writer, Joe Benton, wrote about unintended acceleration for the first time in the summer of 2007, telling the story of a woman in Everett whose Prius took off while she was on the freeway and wouldn’t slow down even as she repeatedly pumped the brakes.

Hood received hate mail from Prius owners when the negative story was posted. “They’re zealots and religious about their cars,” Hood says. “Quite honestly, we don’t give a damn about anything. If people want to drive those things, fine by us, but our job is to criticize and nitpick.”

Then other horror stories rolled in.

One came from Richard Bacon, a Tacoma resident who wrote, “This week our 2008 Prius tried to kill me twice.” First, Bacon’s Prius died while he was driving up his snowy driveway, causing him to slide into oncoming traffic “that just missed hitting me broadside.”

Then, driving with his wife and merging into traffic at 45 mph, he crossed a patch of snow. The Prius locked up, and Bacon lost control and skidded toward a 30-foot drop down the side of the road. “Only a snowbank kept my wife and me from serious injury or death,” he wrote.

Toyota sent out the caution about the Prius’s floor mats about two months after the first story on Hood’s Web site. [This sentence has been corrected since it was first posted. See correction described above.] From a company press release: “If properly secured, the All Weather Floor Mat will not interfere with the accelerator pedal. Suggested opportunities to check are after filling the vehicle’s tank with gasoline, after a carwash or interior cleaning, or before driving the vehicle. Under no circumstances should more than one floor mat ever be used in the driver’s seating position: The retaining hooks are designed to accommodate only one floor mat at a time.”

But floor mats don’t explain why many of the Priuses took off, including the case of the Houston man who parked his Prius in his driveway but left the car running as he walked toward his house. The Prius surged forward through his garage door, slamming into the back of his Nissan Altima.

“It was a pretty rough accident,” says Markus Drunk, a mechanic who worked on the Prius at Autohaus K&H in Houston. “He was lucky that the Altima was parked there, because his backyard is not too long, and the neighbors had a family gathering. It would’ve ran right into all those people, and he was a little shook up over the situation.”

Then there’s Kevin McGuire, who test-drove a Prius one afternoon last fall—a year after the safety notice—at Dorschel Toyota in Rochester, New York.

“There was a wait list to buy one, but they happened to have one in the showroom for me to drive,” he says. “The saleswoman was very knowledgeable on the vehicle, and I was impressed with the car. Everything seemed to be in order.”

The weather was crisp and sunny, and with the saleswoman along for the ride, McGuire drove the Prius away from the city to a hillside road without much traffic. As he recalls the conversation:

“What do you think?” the saleswoman asked.

“I like this feel,” McGuire said.

“Well, go ahead and jump on it and see what you think about the acceleration.”

McGuire stomped on the gas pedal and the Prius zipped forward, but when he took his foot off the accelerator, the car kept going faster. He turned to the saleswoman.

“This is all well and good, but there’s one problem,” McGuire told her.

“What?!”

“It’s not stopping.”

“What?”

“Lookit, we’re still going.”

“Take your foot off the accelerator,” she told him.

“I did!”

“Pull over!”

McGuire hesitated to steer the car off the road, because he was slamming on the brake with all his weight and the Prius wouldn’t stop. Smoke poured from the tires, and finally the car shut down and he pulled to the shoulder.

“She was scared and I was scared, too. We just sat there for a couple of minutes and caught our breath, and then she said, ‘OK, start it up,'” McGuire says. “You could hear the engine rev up, and when I put it in drive—boom! The car took off again.”

This time the car died almost immediately and McGuire pulled over again. After starting it a third time, all was OK, and he cautiously drove back to the dealership. The saleswoman asked a technician to look at the Prius.

“Oh, people put in too many floor mats,” the technician said. “So the accelerator gets stuck.”

McGuire responded, “Wait, this is not my car, this is your car. I haven’t done anything. It’s not me, there’s something wrong with this car.”

Our reporting found just one person currently in litigation with Toyota concerning unintended acceleration. Art Robinson, the man involved in that 2007 crash, wouldn’t discuss the situation (saying his lawyer has advised him not to), but a Toyota spokeswoman confirmed the lawsuit, declining to comment further.

Apparently, hours after Robinson purchased his used 2005 Prius in Tacoma, the car began to handle funny, and as he was driving back to the dealership, the car took off. Robinson stomped on the brake and the emergency brake, but the car wouldn’t slow down.

He exited the freeway and shot through an intersection safely, but then lost control and drove through a convenience store. Robinson escaped before the Prius and the building burst into flames.

“It happened so fast I didn’t have time to be scared then,” Robinson told KING5 News.

Despite Elizabeth James’ injuries, the couple never pursued a lawsuit against Toyota, and even if they wanted to, the Colorado statute of limitations ran out last summer.

“I’m not out to get Toyota; we owned three Toyota vehicles at one time, and we still have a 2000 Sienna and a 2006 Corolla that we’ll drive until they die because they’re good cars,” Ted James says. “The fact that she could crash at 90 miles an hour, well, she’ll say, ‘First the Prius tried to kill me, and then it saved my life.'”

It doesn’t take much of a pitch to sell a Prius, says Johnny “J-Mac” McFolling, a salesman at Houston’s Mike Calvert Toyota.

McFolling wouldn’t drive a Prius, he says, because he’s a big man and everyone in his family is big too, but he loved the car when they all sold at “sticker price or higher.”

“You can tell a Prius owner, not by looking at them, but as soon as they start talking,” McFolling says. “You don’t have to sell a Prius; they’re already sold when someone comes through that door.”

Those buyers haven’t been around much in the past six months, and McFolling says Prius sales have dropped 90 percent since lastsummer while Toyota truck sales have increased. The dealership was selling 25 Priuses a month and could’ve moved more if Toyota had delivered them, but those days are gone.

Mike Calvert sold Riner her Prius, but after the technician told her the car took off because she was low on gas, she wanted nothing to do with it. The dealer offered about $12,000 less than what she’d paid for the car, explaining he couldn’t sell a Prius to save his life.

“He said, ‘The market is soft for Priuses because of gas prices,'” Riner says.

The other owners of runaway Priuses have fared differently:

After his wild test drive, McGuire walked away from the Prius but was determined to buy Toyota. He got a Camry that rattles more than any American car he’s owned, and he says he won’t buy Toyota again.

The Jameses kept their mangled Prius for as long as possible, hoping Toyota would take it to a laboratory for examination, but when their insurance company pressured them, they let it go. Ted James bought a new Volkswagen Jetta six-speed, so if it goes wild, “all you have to do is push in the clutch.”

The Prius that Riner bought brand-new sat in her garage for a while because she hoped Toyota would change its mind about its offer. She just recently set an arbitration date with the company, and given the option of meeting at a dealership or fighting the case through the mail, she chose not to meet.

Unless she eats the $12,000, she’s stuck with a car she’s afraid to drive.