There was something ritualistic, almost sacred, in the guilty pleas last week of Gary Leon Ridgway, the man that much of America now knows as the Green River Killer. Behind tight security, in the gray brick mausoleum that is the King County Courthouse in Seattle, a venue so densely packed with the relatives of the dead that there was no room for the general public, Deputy Prosecutor Jeff Baird intoned, and the penitent Ridgway responded. “You say, ‘I picked her up, planning to kill her,'” Baird read solemnly from Ridgway’s statement of admissions. “‘After killing her, I left her body . . . ‘” And here Baird would fill in the legally required detail of just where Ridgway said he had left each victim, the place where, as the years passed, most became skeletons, then dust. “Is that your statement?” Baird would ask, again and again. “Yes it is,” Ridgway would reply, again and again. “Is it true?” Baird would ask. “Yes it is,” Ridgway would respond. It was a sort of catechism. As the roll of the dead was read by Bairdfrom Wendy Lee Coffield in 1982 to Patricia Yellowrobe 16 years later in 1998, almost exactly the length of Coffield’s short lifetimethe courtroom of Judge Richard Jones took on the mien of a holy place, somehow venerating the victims and serving as the altar for exorcism of unfathomable evil from our midst, an evil that had once seemed to be the work of the devil himself.

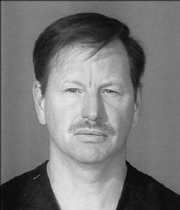

But it was only Gary Ridgway of Auburn, a nondescript 54-year-old painter at the Kenworth truck factory in Renton, a man so plebeian in his tastes and demeanor through the years that no one would have believed that he had murdered at least 48 women, most of them less-experienced prostitutes or runaway teens, many of them in his own house, in his own bed.

The ceremony of the pleas went so smoothly that one might think the participants rehearsed their parts beforehand, as for a wedding or a church confirmation. Once the 48 guilty pleas were entered, the harder work of justifying the deal began. And in this, all sides likewise were prepared.

TRUTH OR DEATH

In agreeing to drop the death penalty in return for Ridgway’s promise to cooperate with the police in their investigation of the horrific Green River murders, King County Prosecutor Norm Maleng made the best of two bad choices. Without the deal, Maleng’s office would almost certainly have been able to obtain Ridgway’s conviction on seven charged counts of aggravated murder, and likely the death penalty as well. But against that likelihood, Maleng’s office had to consider that many of the most important questions posed by the nation’s longest string of unsolved serial killings might never be answeredamong them, the whereabouts of the remains of seven presumed victims, as well as the rather crucial question of whether Ridgway was indeed the killer, or whether there was someone else still out there. In the end, after almost a month’s deliberation, Maleng chose truth over the uncertainty of Ridgway’s state-sanctioned demise.

“The question leaped out to me just as it does to you,” Maleng said in a press conference following the pleas. “How could you set aside the death penalty in a case like this? Here we have a man presumed to be a most prolific serial killer, a man who preyed on vulnerable young women. I thought, as many of you might, if any case screams out for consideration of the death penalty, this was it.”

Maleng went on to note that, almost from the day of Ridgway’s arrest in late fall 2001, he had said his office would not “plea bargain the death penalty.” To many, that meant the way it sounded: There would be no deals for Gary Ridgway, who, as far as anyone now knows, is the worst serial murderer in American history. Maleng considered the choiceslife or death for Ridgway, and truth or obscurity for the victims, their families, and the communityand came to believe his office had a higher duty. “This case squarely presented another principle that is the foundation of our justice system: to seek and know the truth,” Maleng said.

Among the family members who packed the courtroom: Nancy Gabbert, mother of Ridgway victim Sandra Gabbert.

(Pool photo by Peter haley / Tacoma News Tribune) |

“I saw,” Maleng said, “that the justice we could achieve could bring home the remains of loved ones for burial. It could solve unsolvable cases the [Green River] Task Force had spent 20 years investigating. It could begin the healing for our entire community. The justice we could achieve was to uncover the truth.

“When I see the face of justice in this case, it is those young women I see,” Maleng continued. “They deserve to have the truth of their fates known to the world.” So, too, with families of the victims: “They deserve to know the truth about the fate of their loved ones. . . . Finally, the face of justice reflects our whole community. We have all suffered this terrible trauma known as the Green River murders. We deserve to know the truth.”

So, in a way, the proceeding in which Gary Ridgway pleaded guilty to 48 counts of murder last week was a sanctification of the value of truth and its triumph over death.

ORIGIN OF A DEAL

Maleng’s peroration last week culminated an intense period of discussions between the prosecutor’s office and Ridgway’s team of defense lawyers that began last April. Near the end of March, the prosecutor’s office had filed three new murder charges against Ridgway. With four originally filed against him in December 2001, that meant Maleng’s office felt it only had viable evidence in seven of the 49 cases previously attributed to the Green River Killer. Had the seven cases gone to trial, there was every likelihood that the answers to the many heartrending mysteries posed by the other 42 cases might never be known, since, once he was convicted and sentenced to death, Ridgway would have no inducement to tell the truth. And Ridgway was, in the phrase once made infamous in connection with another prolific Northwest killer, Ted Bundy, the only living witness.

With the filing of the three new charges, the defense team, led by Tony Savage and Mark Prothero, knew they would have a short “window of opportunity,” as Prothero put it last week, to explore the possibilities of a deal. Both sides had valuable cards: The prosecutor held Ridgway’s life; the defense had Ridgway’s possible answers to all the questions, including the whereabouts of the missing victims. The defense wanted to open a dialogue with the prosecutor’s office before anyone there made another unequivocal public statement ruling out bargains on the new counts.

The defense knew that Maleng was almost certain to turn down any deal if the investigating police were against it. Fortunately, the police were not. In fact, informal exchanges between the defense team and the investigators over the previous year had led the defense lawyers to think that investigators would welcome a deal for Ridgway’s cooperation. Like Maleng, most of the investigators had become emotionally committed to finding the answers for the suffering families, and if it took a deal sparing Ridgway’s life to get that, it was worth it.

In a series of conversations in the King County Jail between Ridgway and Prothero beginning March 31, a few days after the new charges were filed, Prothero outlined the state’s likely case. With circumstantial evidence such as his proximity to so many of the victims and two types of physical evidence, Ridgway was certain to be convicted on the seven charged counts. His DNA was matched to that of semen taken from three of the first four charged victims. And globules of paint that matched the type Ridgway worked with at the truck factory were found with the body of Coffield, the first victim in 1982, and with that of Debra Estes, killed about two months later. “I had told him we were going to have to have some serious discussions about the evidence, once the state had made its decision” on whether to file any additional charges, Prothero said last week. So on March 31, Prothero visited Ridgway in jail for that serious discussion. “I outlined the strength of the state’s case, along with the difficulty of getting an impartial jury in King County. I did most of the talking. He mostly listened.” Prothero at this point suggested that Ridgway authorize his defense lawyers to try to open negotiations with the prosecutor’s office, but Ridgway was noncommittal.

ON THE EVENING of April 8, Ridgway’s familyhis two brothers and his sister-in-lawvisited him in the jail. They told him that they loved him, no matter what, and for the first time, it appeared that Ridgway gave in to his emotions. All wept.

The following day, April 9, Prothero again visited Ridgway but left before Ridgway was ready to give his answer. Subsequently, another defense lawyer, Michelle Shaw, visited Ridgway. When Shaw reminded Ridgway that his family didn’t want him to die, Ridgway was again moved. He finally told Shaw that he was ready to explore a possible plea deal with the prosecutor’s office, one that would necessarily involve a full confession of every crime he had committed in King County. The day after that, April 10, four of the defense lawyers metSavage, Prothero, Todd Gruenhagen, and Shawto figure out their next step. After some discussion, they decided they needed to know what Ridgway had to offer. Until they knew what they had in their hands, it would be foolhardy to open the bidding. That same day, Prothero and Shaw again visited Ridgway in the jail. “This was the first time he began to speak about the crimes,” Prothero said. “He admitted towell, not everything.”

According to Prothero, Ridgway took the blame for about half of the murders but suggested that there was a second person involved and that he had initially been blackmailed into participating in the crimes. At that point, Prothero said later, he believed that Ridgway was being honest. “I thought it was the whole truth,” Prothero said. The next day, however, Prothero and Shaw returned to see Ridgway. “He acknowledged that the story he had told the day before was less than the whole truth,” Prothero said. At that point, Ridgway essentially confessed to having killed almost all of the Green River victims.

“My jaw dropped,” Prothero recalled, speaking figuratively. Outwardly, he maintained a calm, professional demeanor. He tried to encourage Ridgway to continue being truthful, reasoning that it was the only way to interest the prosecutors in making a deal. After all, information was the only thing Ridgway had that the authorities wanted. “That’s good, Gary,” Prothero told him. “This is what may save your life.”

Prothero and Shaw spent between two and three hours going over the Green River list, and “bits and pieces of the story” began to emerge. By the end of the session, “about 90 percent” of what Ridgway would eventually admit to had been discussed.

Lucille Yellowrobe, bottom, mother of Green River victim Patricia Yellowrobe, and Rona Walsh, sister of Patricia.

(Pool photo by Peter haley / Tacoma News Tribune) |

On April 14, the defense team called Baird to inquire how to proceed. Baird suggested that the defense prepare a proffer, essentially a précis of what Ridgway might be willing to say and the ground rules under which he might say it. The defense decided to evaluate the validity of Ridgway’s information by comparing the statements he had made to them with the evidence the prosecution had provided in discovery. Much of what Ridgway told them checked out, Prothero recalled.

On April 29, the proffer was still taking shape and the defense team met with Maleng and two of his top aides. Maleng reminded the defense lawyers of his office’s long-standing policy against plea bargaining the death penalty.

“Then there was a pause,” Prothero recalled, “a long pause. Then he said, ‘Butin a case of this nature, one has to be prepared to be flexible.” Maleng indicated that he wanted to think the matter over before reaching a decision. The defense team was relieved. “We had our foot in the door,” Prothero said. “At least the door was not slammed shut.”

Maleng subsequently had conversations with King County Sheriff Dave Reichert, who was a young detective when the case began 21 years ago, and the present investigators on the task force, as well as with Baird and other prosecutors. After some three weeks of contemplation, Maleng decided to make the deal for the reasons he would later articulate. On June 4, the defense formally made its proffer to Maleng’s office, and six days later, both sides signed it. Three days after that, Gary Ridgway was removed from the King County Jail and lodged in an open room inside the task force’s headquarters at Boeing Field, so he’d be available to investigators as they tried to find answers that had eluded them for two decades.

Over the next five months, relays of interrogators, led by King County Sheriff’s detectives Randy Mullinax, Sue Peters, Tom O’Keefe, Tom Jensen, and Jon Matsen, along with the sheriff himself, would pose ever-more-pointed questions to Ridgway and get responses that led them back into the woods where so many victims were found so many years ago.

THE EVIDENCE

Last week, just after the guilty pleas, Maleng’s office released a binder containing several legal filings, along with a 137-page “prosecutor’s summary of the evidence.” That lengthy document was preceded by a caution: “Warning: The following summary contains graphic and disturbing descriptions of violent criminal acts and may not be suitable for all readers. In particular, family members and friends of victims are cautioned that this document describes highly disturbing elements of crimes in graphic detail.” For once, this type of warning was fully justified. The contents of the prosecutor’s summary were direct and unexpurgated, capable of turning the most hardened stomach queasy. But the graphically detailed account was critical to establishing the validity of Ridgway’s information, and so, too, to answer the critical question: Was Ridgway really the Green River Killer?

In deciding to release such a disturbingly detailed document, the authorities in essence were acting as a grand jury, reporting to the body politic the facts necessary to evaluate the plea bargain. Apart from all the disturbing details about Ridgway’s methods and motivations, here the critical issue was whether there was evidence that Ridgway was truly responsible for all 41 of the cases that otherwise lacked sufficient evidence for filing charges.

To further the argument that they had the right person, the authorities organized the corroborative evidence by victim “cluster,” that is, the specific area where each group of victims was found. The purpose was to show that Ridgway was uniquely familiar with details of each cluster, that only he could have murdered the victims found in each locale.

In this, investigators had to account for the fact that some details of each cluster site had been published or broadcast. If Ridgway provided details that were already known to the public, that would tend to undercut the validity of his confession. That is one of the main reasons police tried so hard to keep the details secret for so longto distinguish between a false confession and a true one. When Ridgway could provide details that had remained secret, such as a specific location for a body, that supported the veracity of his confession.

THERE WERE EIGHT such “clusters” in King County, including the initial one at the Green River near Kent. It was apparent from the discovery of the victims’ remains over the years that the killer had used several of the cluster sites simultaneously, probably to reduce the likelihood of detection. The other clusters included a wooded area off Star Lake Road between Federal Way and Auburn, areas north and south of Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, a location near Mountain View Cemetery near Auburn, a stretch of Highway 410 east of Enumclaw, an area near the intersection of Interstate 90 and Highway 18, another area off Interstate 90 near Exit 38, and an area farther south along Highway 18.

The Green River cluster, with its initial five victims, was corroborated by Ridgway’s DNA, found with two of the victims, and the paint globules found with Coffield. Along with DNA found with Carol Christensen in Maple Valley the following year, and identical paint globules found with Estes in Federal Way, those victims formed the basis of the seven formal murder charges against Ridgway. Ridgway admitted all seven murders and provided sufficient details of what happened to convince investigators that he was indeed the perpetrator.

For the remaining 41 victims, investigators had to test Ridgway’s recollection of his actions against voluminous documentation for each crime scene, always considering the possibility that Ridgway’s information might have come from reading about the sites. One major cluster police had been unable to link to Ridgway before his cooperation was that of Star Lake Road, where six victims were found in the mid-1980s. Ridgway admitted that he had killed all six there. He correctly pinpointed where he had left his first Star Lake victim, Terry Milligan, identified a blouse that Milligan had been wearing when she was murdered, and described the position in which he had left her, all of which conformed to the known facts. He also identified where he had left Sandra Gabbert’s body and described his return to the scene several times, an account consistent with shoe prints found the following year.

King County Sheriff Dave Reichert, who was a young detective when the Green River murders commenced 21 years ago, listens as his nemesis pleads guilty.

(Pool photo by Elaine Thompson / Associated Press) |

At other clusters, such as the south airport site near South 192nd Street, where five victims were found, Ridgway accurately located the places where he had left each of the victimsinformation that was known only to police. At Highway 410, investigators would find six victims. Ridgway correctly described the places where he had left bodies, including that of Pammy Avent, who had been missing for 21 years. At the Interstate 90/Highway 18 intersection, where three victims were recovered, Ridgway again correctly led investigators to the very locations where the remains had been found, including where he had left April Buttram’s body in 1983. Police this summer located fragmented human remains that matched the DNA of Buttram, who, until then, like Avent, had been on the Green River Task Force’s missing list.

In addition to validating Ridgway’s confessions as to each of the clusters, investigators were able to obtain sufficient corroborative detail about a number of victims who had been found alone, including Marie Malvar. Police only cursorily investigated Malvar’s disappearance in 1983, even though Marie’s father and her pimp/boyfriend led police directly to Ridgway’s housethe same place where he would later claim to have killed so many. At the time, police concluded that there was no reason to suspect that Ridgway had done anything to Malvar, despite the insistence of her father and boyfriend that Ridgway was the man responsible for her disappearance. This year, Ridgway led detectives to the place where he said he’d left Malvar’s body, and her fragmented skeleton was recovered near 65th Avenue South in Auburn, not far from Mountain View Cemetery.

NONE OF THIS is to say that Ridgway’s account of his murderous activities is completely accurate. As investigators noted in their summary, Ridgway’s recollection was spotty, particularly for the faces of his victims. But as Ridgway told detectives, he didn’t really care about their faces, since he knew he was going to kill them even before he picked them up. The gaps in Ridgway’s memory extended to the present whereabouts of four women who remain on the Green River missing list: Kase Lee, Keli McGuiness, Patty Osborne, and Rebecca Marrero. Ridgway told investigators that he had killed Lee, McGuiness, and Osborne, but he either couldn’t recall where he left their bodies, or the site was impossible to search because of subsequent development. As for Marrero, Ridgway insisted that he did not recognize her.

Finally, Ridgway confessed to murdering a number of other women in King County. The actual number he has claimed was not made entirely clear by the evidence summary. The defense proffer refers to 47 to 53 victims, and the summary contends that Ridgway claimed in excess of 60. Doubtless, as the next six months unfold, during which Ridgway is supposed to continue cooperating before being sentenced to life without possibility of release, these and other questions will be the focus of the task force’s attention.

Grim as the corroborating evidence was, the most chilling aspect of the summary report was its venture into the dark recesses of Gary Ridgway’s brain.

THE ROOTS OF MURDER

The summary contains a wealth of material relating to Ridgway’s psychological motivations. In short, exactly as profilers predicted 20 years ago, Ridgway hated women because he believed they had power over him, and virtually all of his actions can be seen as a compulsion to get and maintain control over womeneven after they were dead. Significantly, Ridgway often had difficulty performing sexually unless he was in a dominating positionusually in a position which allowed him to move to murder before his victim knew it, almost always by choke hold.

From left, King County Deputy Prosecutor Jeff Baird, defense attorney Mark Prothero, and Gary Ridgway.

Pool photo by Elaine Thompson / Associated Press |

After considerable prodding by his interrogators, Ridgway finally admitted to numerous instances of necrophilia, sometimes several days after he killed. This is not unusual among murderous sexual predators, particularly the serial kind: Ted Bundy had a similar perversity. What it shows, however, is Ridgway’s mania for maintaining control over his victim as long as possible. Ridgway told detectives that he grew upset each time some of his victims’ remains were found, not because he feared apprehension but mostly because he felt he was being robbed of something that belonged to him.

The origins of this pathology remain to be more fully documented, but at a superficial level, one can certainly point to Ridgway’s relationship with his now- deceased mother as an example of early trouble. Ridgway told detectives that he wanted to stab his mother, as well as have sex with hertwo clear manifestations of the desire to take control and to humiliate. Ridgway told detectives that he regularly wet his bed until pubertyalso a frequent attribute of serial offendersand that his mother shamed him for this. Later, Ridgway would blame part of his murderous nature on failed relationships with significant women in his life, including his wives. Ridgway’s pathology permitted him to see others only as objects, whether desirable objects or threatening ones, and prevented him from establishing true intimacy with anyone. As Ridgway himself put it, he lacked “caring.”

Unlike Bundy, Ridgway’s intelligence tested out significantly below normal. He has an IQ of 82. The remarkable thing about Ridgway’s depredations is how completely dedicated he was to this grim avocation, to the point of scattering false clues to lead his pursuers astray. What modest intellect Ridgway had, he devoted to thinking about how to get victims, how to kill them, and how to avoid detection. In this, too, Ridgway matched well with the profile drafted at the beginning of the investigation and was remarkably consistent with other apprehended serial murderers, who eventually begin to think of their killing as their “career.” And in this, Ridgway took pride: This was, he said, the thing that made him stand out in the world, something uniquely his.

NIGHTMARE’S END

“Our Green River nightmare is over,” Maleng said at his press conference following the pleas. While everyone wishes it were so, the truth is, it’s not that easy to awaken from. Apart from the question of how many Ridgway actually killedwhether 60 or more, just in King County alonethere remains the issue of other similar murders still unsolved that Ridgway has not claimed as his. If Ridgway didn’t kill these others, who did?

And there are other, larger, more systemic questions that need to be addressed before the nightmare is truly over. Deputy Prosecutor Baird, in describing Ridgway’s crimes last week, correctly noted that Ridgway preyed upon the most vulnerable victims, virtually all of them participants in an underground, illicit economy. As Ridgway himself noted, killing prostitutes was easy, because nobody really missed them. What a commentary.

In custody of the Green River Task Force, Ridgway on a cluster tour.

(King County Sheriffs Office) |

Ridgway was able to kill so many people, the vast majority of them desperate young girls who weren’t worldly enough to anticipate the danger of a seemingly ordinary man, because for a time police failed to notice that a serial killer was at work. Meanwhile, courts and social services failed to divert victims from their fatal path. The social systems designed to prevent this sort of victimization have been transformed over the years into a revenue stream: with fines, we have in effect imposed a tax on prostitution, caring little about the dangers that the activity engenders.

There is no way at present to prevent the emergence of other deadly sexual predators. Ridgway is only the latest of a steady stream of sexually dysfunctional killers who have graced our headlines and airwaves over the past 30 years. The roots of this behavior are so deep in society’s various pathologies, misogyny among them, that it will take years, if not centuries, to remove them, if that’s even possible. Nor should we expect to be able to eliminate prostitution. As long as there are women and girls desperate enough for money to take the trick, we will not be rid of this problem, and it does no good to pretend it’s not there.

WHAT WE CAN DO, what we should do, to avoid another Green River nightmare is begin right now to improve those warning mechanisms that were so fatally ignored 21 years ago. Periodic outside audits of police missing-person investigation units would be a useful step; so would creation of intensive, inpatient, sex-separated, months-long diversion programs for those arrested for prostitution, particularly those who aren’t old enough to vote. The jails and courts might cooperate by requiring every person arrested for prostitution and victims of domestic violence to provide DNA samples. Young women arrested ought to be required to have dental X-rays, along with an explanation for this: Someday we might need these pictures to identify your bones.

In the Middle Ages, we would have burned a living ghoul like Gary Ridgway as a witch. Later, the English would have drawn and quartered him to make double sure the evil was truly gone. The French invented the scientific guillotine for people like him. More recently, we used electricity or cyanide, and now, a potent Valium cocktail is shot into one’s arm.

We won’t be able to do these things to Gary Ridgway, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Instead, we can and ought to look into the abyss that Gary Ridgway represents to see what we ourselves are made of. That’s where we’ll find the ultimate truth behind the Green River murders.

Carlton Smith covered the Green River murders for The Seattle Times from 1983 to 1991. He is the co-author, with Tomas Guillen, of The Search for the Green River Killer (Penguin-Onyx, 1991). Since leaving the Times, Smith has written 16 other books about homicide, including five about serial-murder cases.