This story was originally published on February 25, 1987, under the title “Proud Tower.” It is being resurfaced as part of the Weekly Classics series.

It was the first day of fall quarter, 1964, at the University of Washington. A nervous freshman, I met several high school friends at the flagpole overlooking what was then a grassy quadrangle west of the Suzzallo Library. After some strained badinage and heartfelt wishes of good luck, we went our separate ways—they to their first classes and I on a private expedition to the vast Gothic edifice. The great stone staircases within the library led me to the second floor and the low, padded doors of the Graduate Reading Room. I opened one and stepped out onto the cork floor, aware of great space, an almost palpable silence, and the sweet smell of warm dust.

High above was the room’s ogival vault, with ceiling work studded with gilded rosettes. My gaze fell softly down the tall traceries of the windows, down the dependent lanterns to the acorns and oak leaves crowning bookshelves and the immense oak slabs of lamp-lit desks. If others were there that morning, I was unaware of them, wrapped in my private vision and stilled by all that magnificence, richly affirming all of my hopes and dreams.

The grandeur was what its builders intended, as did the man who ordered its building, Henry Suzzallo. To his critics it was wasted space, but Suzzallo conceived it as a temple of learning whose scale would manifest the spirit and ideals of a university of a thousand years. It remains the grandest building on campus, but it was only part of the statement Suzzallo intended. East of his cathedral he planned an immense 310-foot bell tower, to proclaim the dominion of his institution throughout the commonwealth.

Suzzallo’s proud tower was never built. His tenure as president of the University of Washington marked its transition from a glorified frontier college to a cosmopolitan university, but it was a move that went tragically awry. If the reading room is a vision realized in stone, the missing tower is symbolic of a dream that failed.

Like other state schools, the University of Washington was founded as an American experiment in education. By marrying the medieval institution of the university to the forms of modern representative government, it was hoped that higher learning could be democratized and made more accessible. The marriage has had happy issue, but the relationship between the partners often has been strained. More than one state school, following its natural inclinations to grow and aspire to greatness, has found itself a convenient and vulnerable target. The pattern continues to this day.

When Governor Isaac Stevens prompted the first territorial Legislature to memorialize Congress for a university land grant, he added another plum to the contest over placement of public institutions. The chief prize was believed to be the capital, but Methodist minister Daniel Bagley convinced the citizens of Seattle that the university would ultimately prove a greater benefit. In 1860 the decisions were made: Olympia got the capital, Walla Walla the penitentiary, and Seattle the university.

Immediately the townsmen set to work building the great white box atop a small rise—Denny’s Knoll—north of the town’s commercial heart, where the Olympic Hotel now stands. For over 30 years it remained one of the town’s more prominent structures and a symbol of its pride. In September 1861 its doors opened to its first classes, but if the territory had little problem producing politicians and criminals, university students were another matter. That fall the university’s enrollment consisted of one freshman; the rest were elementary and secondary students. It did not award its first degree until 1876, and its classes did not become exclusively postsecondary until 1895.

Growth was slow at first, but it accelerated as Seattle boomed. By 1895 the university had left the wooden box atop Denny’s Knoll and moved into the solid stone elegance of a new building, Denny Hall, on an extensive campus overlooking Union Bay. The development of a college of mines and engineering, and a law and graduate school marked the emergence of a true university, and by the middle of the new century’s first decade, the number of registered students exceeded 1,000. Moreover, the development of a marine science station at Friday Harbor in the San Juan Islands and a department of Oriental history and literature was evidence of the university’s increasing involvement in the region’s maturing sense of itself and its position on the rim of an emergent Pacific community.

This first flowering of the university coincided with Seattle’s emergence as the dominant city in the Pacific Northwest. In 1,309 the city’s celebration of the Alaska, Yukon and Pacific Exposition on the campus announced its arrival to the world and its confident expectation of greater things to come. By association, the university was making similar claims.

Once the AYP Exposition closed, many of its buildings were used by the growing university, but most of them deteriorated rapidly. By 1914, with the university’s student population nearing 3,000, many buildings had been condemned, and classes were held in overcrowded rooms, attics, and a motley collection of shacks. This decaying physical plant, however, was not the only problem generated by growth.

When it had resided in its white box atop the Knoll, the university was a homespun institution whose poverty appealed to the tender instincts of Seattle’s citizens. The fact that it was primarily a grade school strengthened sentimental ties, for many residents received their education there. Presidents like Daniel Bagley and George Whitworth, who were also churchmen, were revered; teachers like Asa Mercer and Edmund Meany, who went out into the lumber camps in search of scholars, were regarded with genuine affection. It was not uncommon to see a trustee like Arthur Denny patching the roof or a president fitting a new stove pipe.

As the school grew, however, it shed its pre-college classes and the gap between it and the rest of the community necessarily widened. As students from elsewhere in the state arrived in increasing numbers, Seattle’s complement declined; by 1914, it represented little more than half of the student body. These things contributed to the natural estrangement of town and gown. Then, at the turn of the century, other factors aggravated the problem.

In the early years, it had been natural to look upon the university as Seattle’s school. Even as it grew more independent of the city, that view remained in force in outlying areas, especially east of the mountains. The establishment of a state college and agricultural school at Pullman and normal schools at Cheney, Ellensburg, and Bellingham created rivals for state funds, and the university’s appetite for public funds became a cause for complaint. As the populist spirit of the times matured into progressivism, rural groups increasingly looked upon cities as threats to their well-being. In the cities, too, discord grew between groups of citizens and what they believed to be corrupt business interests and municipal officials. There were calls for reform, and the university was a focus of debate.

The university first came under attack when it sought to negotiate a dispute with the Northern Pacific Railroad over a right-of-way along the southern margin of the campus. The agreement that was reached satisfied both parties, but critics called it a sell-out to a hated corporation that historically had been Seattle’s nemesis. Another issue involved the university’s original ten-acre site downtown, which had increased in value as the city grew around it. Rather than sell the land, the board of regents decided to lease it, and they agreed to a system of fixed rents to encourage building by the lessee. When land values soared, the rents came to appear ridiculously low, and it “was not hard to imagine the regents in cahoots with the builders. Heeding their critics, the regents sought to maximize income by selling agricultural land in Eastern Washington at full value. This only added fuel to the fire, since farmers believed they should be able to buy state land at low prices. The regents were now accused of being greedy speculators.

On the other hand, spirited arguments for progressive reform emanating from professors such as J. Allen Smith drew charges that the university was teaching socialism. There were calls for Smith’s dismissal. Noisy political debate on campus and student requests to hear candidates for public office prompted the regents to ban such speakers. President Thomas Kane was forced to ban a speaker he had previously invited, whereupon a group of students threatened to invite him to speak on their own. In turn, Kane promised to expel any students who were involved.

The students later revenged themselves. They protested the acceptance of a gift of chimes from Alden Blethen, a regent and editor of The Seattle Times. Blethen’s cordial relationship with Seattle’s chief of police during an administration tolerant of gambling and prostitution was at issue, so the students claimed that accepting a gift from such a figure would tarnish the university’s image. They threatened to publish a petition in the Daily protesting the gift on the day of the acceptance ceremony. Kane had the presses shut down, but the students printed their petition off-campus and distributed it anyway.

Such antics turned critics purple, dismayed the university’s friends, and saddled Kane with the reputation of being too weak to discipline his students. In 1913, the board called for his resignation. He refused, accusing the board of being reactionary; they in turn accused him of being inadequate for the job. The sorry business was played loudly in the press. After charges of politics were hurled back and forth, on January 1, 1914, Kane was dismissed.

It was obvious that the university was at a critical juncture and that strong leadership would be required to restore morale and give it direction. Newly elected Governor Ernest Lister replaced four of the regents he regarded as too political and directed the reconstituted body to search for a new president.

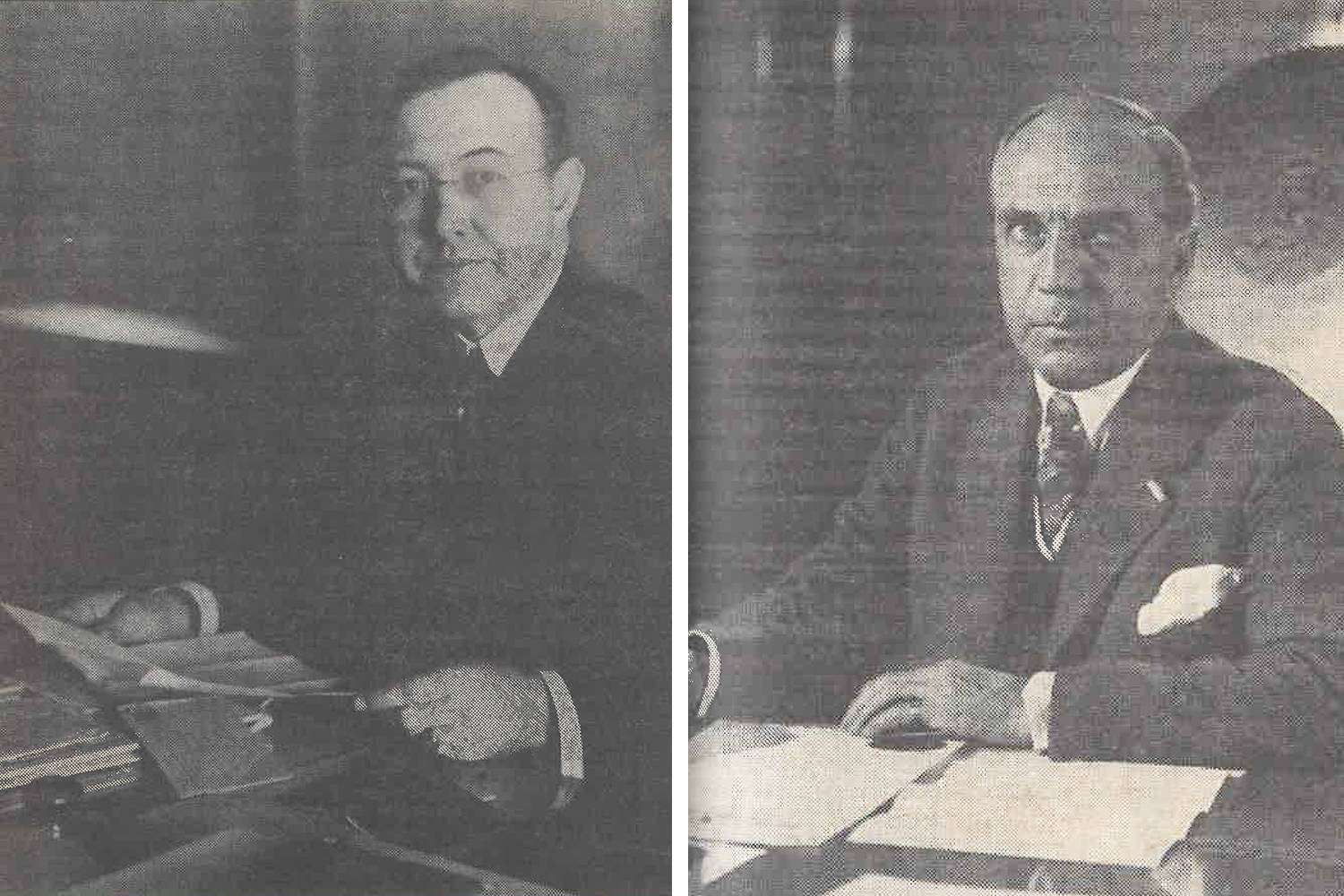

Between 1900 and 1914, Washington’s population jumped from 518,000 to 1,408,000. Apart from a brief recession in 1907, its economy boomed. The Northwest’s prospects for the future Seemed limitless, and the university’s supporters felt it was on the eve of greatness. But who could they get to come to a tatty campus to take the reins of an institution that had been roundly accused of being a tool of big business and a hotbed of socialism? Cunsiderable excitement attended the arrival in Seattle of University of Chicago Dean James Angell, but after a long hard look at the campus and its problems, he took the next train east. At this point Frank Graves, who had been president before Kane, lobbied hard for the man he thought best for the job, a bright young professor of education at Columbia University, Henry Suzzallo.

Anthony Henry Suzzallo was an outstanding example of that ideal of the time, the self-made man. His father, Peter Suzzallo, had been born of Italo-Slavic parents in Ragusa (Dubrovnik) on the Dalmatian Coast of what is now Yugoslavia. He went to sea at an early age and landed in New York in time to hear of the 1849 gold rush. Signing on as a mate on a ship bound for California, Peter arrived there in 1852 and started mining in Placerville with some success. Eventually he returned to Ragusa and married a distant cousin, whom he brought back to Placerville. Illness and poverty forced them to move to San Jose where, on August 22, 1875, a son was born, christened Anthony Henry. He was the eighth of nine children, of whom only four survived to adulthood.

He was a frail child, prone to illness. His record of work at public schools was distinctive for its lack of promise. Two San Jose clothiers, Emil and Jesse Levy, employed him as a clerk in their store and encouraged him to get an education beyond high school. With money they loaned him, he entered the state normal school and graduated two years later in 1895. In the fall of that year he entered Leland Stanford Jr. University, which had opened its doors in Palo Alto only four years before.

At Stanford, Suzzallo came into his own, drinking deeply of the spirit of academic life and progressive reform. To pay tuition, he took a year off in 1896 to teach in a rural school in Alviso, where he was fired when he refused to join a political club. At Stanford, law and medicine beckoned, but his own experience of its tribulations and the opportunities education offered people like himself inspired him to go further in that field. Working part time as a principal of an elementary school in Alameda, he graduated from Stanford in 1899 and worked toward an advanced degree at Teachers College at Columbia.

From principal he became the deputy superintendent of San Francisco’s public schools, and his work at Columbia was of such promise that he was made a lecturer before he received his PhD in 1902. After that, he moved with ease to professorships at Stanford, Yale, and Columbia. He became the protege and friend of Columbia’s president, Nicholas Murray Butler.

This part of Suzzallo’s life could have been written by Horatio Alger. Its progress was as neat as an ascending curve, but its apparent simplicity is deceptive. Along the way, Suzzallo made some important breaks in his life. Politically he went his own way, becoming a liberal Republican while his father remained an ardent Democrat. Born and raised a Roman Catholic, he left the church and later attended Episcopal services regularly although he never became a member of that body. He became a Mason and attained high rank in the Scottish Rite, southern jurisdiction. The move from Roman Catholicism to Freemasonry might suggest a desire to distance himself from an uncomfortable immigrant background, but it more accurately reflects his profound faith in the secular institutions that had rescued him from an anonymous poverty. Toward the end of his life he addressed a luncheon of the Pilgrims Society in London and caught his listeners’ attention by telling them that he did not have a drop of Anglo-Saxon blood in his body. He added that he did not have a thought in his mind nor aspiration in his heart that came from other than the Anglo-Saxon tradition transmitted through the American system of public education.

Typical of his time and rather like John Dewey, he developed an extremely broad view of education, seeing it as far more than simply a means of training students to be useful citizens. Through it, he believed the economic, social, religious, and political disputes troubling the nation could be mediated and the life of the Republic made harmonious. Education was a kind of fourth branch of government by which the other three could be made more effective.

Such ideas put him in the vanguard of educational and social reform, and his eloquence made him a natural spokesman for progressive ideas, as well as a popular lecturer and teacher. In 1907, friends urged him to run for mayor of San Francisco as a reform candidate, but he was unable to satisfy the residency requirements. In 1909 President Butler appointed him to the new chair of educational sociology and he occupied a seat in the faculty of political science as well. His work brought him into national prominence, and it is said that President William Howard Taft would have appointed him to the U.S. Commission of Education had Taft not needed to appoint a southerner to that post.

In 1912, he married Edith Moore, a Chicago woman who was the niece of a prominent Seattle family and a frequent visitor to this city. When it became known that the University of Washington was looking for a new president. He and Edith signaled their interest. On Frank Graves’ suggestion, the board sent a committee to Columbia to interview Suzzallo. Butler was loath to lose a man he counted among the best and most promising of his faculty, but he endorsed Suzzallo warmly. “I assume,” he wrote, “that it will be the ambition of the people of the state of Washington to strengthen and supporter their university in a way that will make it the center of enlightenment, culture, and intellectual leadership for the whole Northwest country. To guide and inspire the university in such an undertaking, there is no man in America seems to me to possess more qualities, both in mind and in character, that are of the first rank and of the highest importance, than Professor Suzzallo.”

Word of the board’s action met with local approval save for a few, like the editor of the Seattle Sun, who worried that Suzzallo’s connections with Columbia might carry a desire to impose Eastern ideas on a Western institution, and he urged the regents to “investigate him a bit.” However, in May the board invited Suzzallo to Seattle for further interviews and he spent the evening of the 17th at the New Washington Hotel in conference with Governor Lister and the assembled regents. The next morning they announced his unanimous election as the 16th president of the University of Washington.

The regents congratulated themselves on getting such a man, and Suzzallo returned the enthusiasm. “I have caught the Washington spirit,” he said in his first remarks to the university. “It is the opportunity … to develop a university that will take its place with the best in the country, and which will stand, backed by the community, a vigorous and responsive expression of the community’s desire for the best in life that has brought me here,” he said later.

In the bright spell cast by these words, Suzzallo appeared on campus on July 7 in the company of professors Edwin Stevens and John Condon and, tray in hand, took his place in lunch line at commons. He was short, stocky, and dark, but his unprepossessing build failed to mask the impression of energy. “Thin black hair,” wrote an observer from the P-I, “stands high above a prominent forehead. The small gray-green eyes are very much alive. Dr. Suzzallo speaks in a somewhat high-pitched voice of light quality and he answers and propounds theories without hesitation. His manner gives the impression of conviction without dogmatism.”

He soon discovered an institution rife with problems and riven with bitter factional disputes. He moved quickly to end the rancor, resolving the disputes he could and inviting those who would not be reconciled to leave. Within a few weeks, observers noted a marked improvement in the university’s temper

Next he worked to improve the school’s image within the state. Within a few months be had traveled 8,000 miles and delivered about 100 speeches. “In this state,” he said at one stop, “I find there is a great shortage of the razor clam. There is also a great shortage of the Dungeness crab. … There has also been a great shortage of sockeye salmon on the Puget Sound. … What does this suggest? The need of a school of fisheries, equipped to investigate the causes of this shortage by biological research and by other lines of investigation, and to equip men for one of the greatest industries of Washington.

The emphasis upon serving the economic needs of the state was bold for its time. Within a year he called for the creation of schools of fisheries, marine engineering, commerce and business, and architecture. He also worked to educate the public that the university was not like a business or a government body: its members could not be treated like employees or subjected to the vagaries of public opinion. While a university could be administered with an eye to fiscal economy, a different kind of economy obtained in the realm of intellect and creativity. At the same time, he appointed advisory boards made up of representatives from the outside world who would act as consultants to keep the various departments in touch with the community’s needs.

With great enthusiasm, he inaugurated a long-overdue building program. A master plan drawn up by the distinguished local architectural firm of Bebb and Gould described a vast new campus made up of two quadrangles, one devoted to the schools of home economics, commerce, the liberal arts, and education, and the other to the natural sciences. The axes of these quadrangles, angled like the wings of a great bird in flight, met at a central point in a wide plaza dominated by a monumental library, a cathedral of learning.

The breadth and depth of Suzzallo’s vision was captured in the phrase with which he liked to describe his institution, “the university of a thousand years.” It conjured an image of magnificent aspect. Perhaps because of that, challenges to its ambitious scale were not long in coming.

The first came from the state college at Pullman. In Suzzallo’s mind the university rested at the pinnacle of the state’s educational system with all other schools subservient to it. Pullman was an agricultural school; it might become a great agricultural school, but it should aspire to no more than that. “If We are going to have two institutions of higher education,” he wrote regent William Perkins shortly before his arrival in Seattle, “we do not want two mediocre colleges; rather one great university and one great vocational college for agriculture.” The people at Pullman thought differently. Their school derived from an act of Congress different from the one that had given birth to the UW, and they saw no reason why the eastern part of the state should not have an institution equal to that in the western part.

In November of 1916 Ernest 0. Holland, a student and roommate of Suzzallo’s at Columbia, was made president of Washington State College. It was hoped that the friendship the two men shared would help ease the longstanding dispute. At first, such hopes seemed reasonable as the two men publicly proclaimed their mutual affection. At a luncheon given in their honor at the College Club in February 1917, Suzzallo addressed the problem posed by the American spirit of individualism in the West. In its extreme form he believed it degenerated into provincialism. “Thus we have selfish rivalries. Cities, institutions, and individuals have quarreled and cherished small jealousies. Cooperative endeavor should succeed provincialism, and the two state institutions should lead the way.”

Very soon it became clear to Holland that Suzzallo’s idea of cooperative endeavor was simply for Holland to agree with him. To Suzzallo duplication of curriculum was wasteful and inefficient. Pullman was an agricultural school; if its students wanted other classes they could come to the university. Of course, this view was resisted fiercely at Pullman and by Eastern Washington newspapers. The battle was soon joined over who would teach what.

A legislative survey committee determined that, given the differences in historical and economic development between East and West and the needs of each region, duplication of curriculum was not necessarily inefficient. It concluded that liberal arts courses should continue to be taught at Pullman, but that the school of engineering that Pullman coveted should remain at the university. The survey’s report was a compromise that both schools accepted, but it did little to quell the debate.

Suzzallo kept up the pressure against duplication by appealing to the governor, but the report was written into law with only minor changes. Things remained almost precisely where they were before the issue blew up, but the animosity between the two schools was getting greater. The presidents who had once been warm friends now eyed each other coldly as adversaries. For Suzzallo this falling-out would have dire consequences.

The dispute, however, was soon submerged in the clamor surrounding the United States’ entry into World War I. Enrollment at the university plummeted as students left for the war, but their places were taken by military units that trained on campus and were housed in barracks. In addition to administering a university on a war footing, Suzzallo assumed other responsibilities, among them the chairmanship of the State Defense Council.

A major task of this council was to settle labor disputes. In those years “labor dispute” was often a euphemism for violence. The state had only recently witnessed a particularly bloody episode. A 1916 labor dispute in Everett led to a savage bloodletting in the suburb of Beverly Park and even more savage carnage when a mob of vigilantes fired into a crowd of, strike sympathizers on the ship Verona as it tried to land. With passions on both sides still running high, the creation of a legislative council to settle labor disputes was a sure way for Suzzallo to make more enemies. The list was beginning to grow.

When the United States went to war in April 1917, it did not take workers long to realize the enormous leverage that the increased demand for labor gave them. Early in the summer, timber workers began walking off the job. The strike mushroomed, and by July 65 percent of the lumber mills and 95 percent of the shingle mills in Washington were shut down. Owing to the labor shortage, mill owners were unable to hire scabs but most still refused to negotiate. At the request of panicky fruit growers who could not get enough crates for their produce, the Defense Council held hearings in Yakima and recommended that the governor call in federal troops. The strike spread. Workers reduced their demands to one, the eight-hour day, but still the owners remained adamant. At this point, Suzzallo offered a compromise: workers would work a ten-hour day until January 1, 1918, after which there would be a referendum on the eight-hour day; if the workers voted it in, industry would have to accept.

The compromise was widely praised, but the owners refused to consider it. Governor Lister next proclaimed an eight-hour day, and the mill owners ignored it. The Industrial Workers of the World called for a general strike on August 20, which failed to materialize. In the midst of the stalemate, workers facing a hungry winter drifted back to their jobs, carrying their strike with them in the form of a slow-down. That threatened to reduce the output of lumber for war industries, particularly airplane production.

Finally, the government acted. IWW leaders were arrested and jailed; the eight-hour day was enacted into law. If a mill owner objected, the government, which had just taken over the railroads, simply cut service to his mill. The owners had to comply. The rabid anti-unionists, such as David Clough and his son-in-law Roland Hartley of Everett’s Clough-Hartley Mill, never forgave Suzzallo for the role he played in their defeat. Suzzallo now had his most dangerous enemy.

The war wound down. The demand for labor, particularly in the shipyards, declined. Now unrest began to build in the metal trades. No less a figure than Felix Frankfurter, chairman of the War Labor Policies Board, credited Suzzallo with solving several national labor problems, but in Seattle, animosity continued to build. On February 6, 1919, the shipyard workers spearheaded Seattle’s famous general strike, which lasted for a peaceful five days. Suzzallo’s role in calling out federal troops cost him much of the labor support he once enjoyed.

The fever of war and strike eventually subsided, and Suzzallo was once again able to give his full attention to the university. Like many other institutions, the UW had suffered the effects of the war’s tumult. By 1920, its population leaped to 4,740, a 65 percent increase in one year. With the depletion of graduate schools during the war, there was a dearth of teaching scholars. Suzzallo crisscrossed the country, beating the bushes for qualified teachers, but he had to settle for those of moderate attainment at best and graduates from the university itself. The school developed a more parochial outlook than before. The postwar period was a time of uneven prosperity, and economic dislocations were particularly severe in Washington, whose economy had only begun to mature. In spite of the growth, the university endured years of privation. Even as Suzzallo increased the number of his faculty, the money available for salaries remained relatively fixed. A disparity now emerged between a few well-paid older professors and many poorly paid younger ones who had little hope for advancement. Faculty morale sagged.

Suzzallo’s time was now being spent analyzing statistics and student-clock-hour ratios, hoping to pare saving from an already lean budget. This dry statistical approach to administration and Suzzallo’s own tendency to appropriate authority created a gulf between him and the faculty, which increasingly came to regard him as an aloof authoritarian.

One of the few pleasures Suzzallo enjoyed during these years was the planning and construction of new buildings. The proliferation of temporary buildings during the war had littered wth shacks, but now impressive buildings in collegiate Gothic style were erected on the liberal arts and science quadrangles. His greatest interest centered on the library, which began to take shape on the greensward east of Meany Hall. Bebb and Gould submitted a plan for an immense triangular structure to be built in stages. The first, the west wing, would house a great room, 56 feet wide, 212 long, and 96 high. Adjoining this on the east would be a rotunda and the great bell tower. Northern and southern wings would be built from the ends of the west wing around the tower and would meet in a large structure that would house the book stacks. The cornerstone was laid in 1924 and soon the steel framework of the great Gothic hall began to rise above the campus.

But as Suzzallo’s vision of the university’s soul began to take form, the body was placed in jeopardy by the election of 1924. Running for governor that year against Democrat Ben Hill was the man who had it in for Henry Suzzallo and who served to focus the discontent against him and his university: Republican Roland Hill Hartley.

Both men resembled one another more than either would have cared to admit. Like Suzzallo, Hartley had been born into poverty as the son of an itinerant Baptist preacher in rural New Brunswick, Canada. In the 1870s, Hartley and his elder brothers moved to Brainerd, Minnesota, where he worked briefly as a hotel clerk, a “cookee” in a lumber camp doing odd jobs, and then as a logger hauling timber with a horse team and working rafts of logs down the Mississippi to St. Paul during the spring flood. In the summer months he hired out as a laborer and teamster on the North Dakota prairies. His schooling was spotty, but he was able at one point to attend business classes in a Minneapolis academy. He did well enough to become secretary to the mayor of Brainerd, getting his first taste politics. The hunger never left him.

Eventually Hartley became bookkeeper and private secretary to David Clough, a timberman politician in Minnesota who eventually became its governor. In 1888 he married Clough’s daughter, Nina. Hartley was a short, spare man with hard blue eyes and thin hair. Later photographs of him display a stern if studied rectitude, not without vanity. During an 1898 Chippewa uprising, he was the governor’s representative to a military attachment which got involved in a shootout with some drunk Chippewayan men. Hartley ever after styled himself Colonel and formed a lifelong fascination for the military.

In 1900 Clough moved west to establish a lumber mill at Everett, a town boomed into existence by his St. Paul friend and associate, James Hill. Hartley accompanied the migration of Clough’s relatives and in-laws to Hill’s barony and helped manage Clough’s interests. He did it well enough so that Clough’s company became the Clough-Hartley Company. They built the largest shingle mill in Everett, a feudal bastion in which bloody-handed workers toiled like serfs and unions were anathema.

In 1909 Hartley ran for mayor of Everett and won. His tempestuous single term was marked by his slashing the municipal budget after the town voted out Saloons—the major source of

revenue—in a spasm of moral righteousness. He was elected state representative in 1914—Hartley was now 50—and he worked to reduce government and expenditures, themes dear to his heart and sure vote-getters in hard times. On one occasion he sought to amend an appropriations bill in order to prevent the UW, which he labeled a hotbed of socialism, from teaching political economy. This amendment was easily dismissed by the university’s friends, but Hartley did not forget. He may not have been present in Everett on the day the Verona tried to land at the city dock, but his response to the massacre seems to have been a hardening of his attitudes against unions. In 1916 he ran for governor on the single issue of the open shop and industrial freedom; he lost, but not by much.

During the war the Colonel enlisted in the National Guard, obtained a commission as captain in the regular Army, and would have been sent to Europe had not peace spoiled his plans. In 1920 he ran once more for governor on a broader platform than before, hoping to capitalize on the fears generated by the Seattle general strike and the Centralia Massacre, but he lost again. During this period, however, he made his first million from a lucrative contract stripping trees off the Tulalip Indian Reservation. In Mill Town, the historian Norman Clark records a wonderful story Hartley himself told about walking into David Clough’s office, slapping the evidence of his fortune down on his desk, and shouting, “There, you old son-of-a-bitch, I told you I could do it!”

The third time Hartley ran for governor, 1924, he won. Part of his success was owing to his colorful sense of style. Hartley was never one to use a fly swatter when a sledge hammer was available. He gleefully branded his opponents “goggle-eyed jackasses,” “bolshevists,”or—a favorite—“pusillanimous blatherskites.” Hartley also drew support from the profound discontent that troubled the state and nation in the early 1920s. War, the Russian Revolution, economic crisis, and social change had come so fast and struck with such force that the national mood of confidence before the war was replaced by a sense of fear, individual helplessness, and an anger that lashed out at real or imagined dangers. The 1924 campaign was a particularly grotesque one in Washington politics, with the Ku Klux Klan fomenting hatred against blacks, foreigners, Jews, and Catholics. Government intervention in private life during the war had fostered a backlash. Even though many of the national programs disappeared with the armistice, many still believed government was too big and unwieldy. Sensible of this, Hartley ran as the Republican nominee on a platform in which he promised to carry out a “business survey” of state government to cut out waste and reduce taxes.

His inaugural address told his audience what they wanted to hear: “We may as well face the fact, and face it squarely, that we are too much governed. The agencies of government have been multiplied, their ramifications extended, their powers enlarged, and their sphere widened until the whole system is top-heavy. We are drifting into a dangerous and insidious paternalism, submerging the self-reliance of the citizen, and weakening the responsibility and stifling the initiative of the individual. We suffer not from too little legislation, but from too much. We need fewer enactments and more repeals. We need to call a halt until the majority’s pocketbook catches up with the desires and clamor of the minorities for more government and increased appropriations.”

Cheers greeted these words. Fewer huzzahs followed his call to reduce the money spent on highways or his plan to end state support of reclamation and seed loans to farmers, or his caustic denunciation of child welfare programs and education. But while legislators, reformers, and editors fumed, Hartley enjoyed real public support.

As Hartly drove his program through the legislature, he moved toward a confrontation with the university and its president, whom he came to regard, with some reason, as a political threat. As a leading figure in the circles of Progressive reform and an exemplar of cosmopolitan values, Suzzallo had the support of many urban leaders. But his style and the very nature of his institution, grossly characterized as a haven for reds, foreigners, and sneering fops, rendered, him suspect in rural areas and among ordinary folk. In 1925 more than 55 “percent of the state’s people lived in urban areas, but the shift in population from a rural to an urban base had been recent. Those in the eastern and southwestern parts of the state feared and resented the loss of their power and influence to the cities of Puget Sound.

Duncan Dunn, a Yakima sheepherder, state representative, and regent of Washington State College, was Hartley’s campaign manager and political confidant. With the help of WSC President Ernest Holland, whose bitter resentment of Suzzallo found a receptive ear in the new governor, Dunn labored mightily to cut the university’s appropriations in the 1925 legislature. Dunn’s activities drew a protest from Suzzallo, who accused him in a speech of being the worst enemy of the UW in the state. Dunn responded by calling attention to Suzzallo’s annual salary of $18,000, the highest paid anyone in the state and almost double Holland’s.

The politically wise saw Suzzallo’s attack on Dunn as an oblique attack on Hartley, and Dunn’s reply as Hartley’s response. Concerned over where this might lead, the UW regents adopted a resolution of confidence in their president, asserting that the “continuance of Dr. Suzzallo in the presidency of the university is a matter of vital importance to the state as well as the university.” Dunn attacked Suzzallo again in a speech to Grangers in Yakima. He stroked the rurals’ xenophobia by alluding to the president’s Italian background, identifying him at one point as ”Knight of the Garter of

Italy or some other title of nobility by virtue of the favor of the fascist government of Italy.”

Spurred by the attack, Suzzallo undertook a statewide tour before the November legislative session, to rally the university’s supporters. He openly attacked the administration, putting him squarely against the governor. Hartley responded by refusing to attend and speak at the celebration honoring Suzzallo’s tenth year as president.

On November 10, Hartley introduced a measure to the legislature that produced audible gasps of amazement. He had long been displeased by the practice of the university and other schools of constantly approaching the Legislature with requests for special—and in his mind, hefty—appropriations. To him, such practice was inefficient and evidence of budgetary indiscipline. To solve the problem he proposed to abolish the boards of regents of the UW, Washington State College, and the normal schools, to abolish the state Board of Education, and to pass a constitutional amendment abolishing the office of state superintendent of schools. He would replace these with a single superboard made up of his appointees, who would manage the budgets of all state educational institutions from kindergarten to graduate school. “Don’t misunderstand me,” he sought to assure the stunned legislators. “l am not contending for less education, but for more education for less money.”

The proposal was met with outrage from educators as well as legislators. It was quickly tabled. It split the Republican Party, but its public support would not evaporate. In a revolt actively supported by the university, the legislature voted to increase funding for higher education. Hartley vetoed the bill; the veto was overridden. In this massive repudiation, Hartley believed he saw Suzzallo’s fine hand.

The UW was now under the microscope, its long march to distinction called into question. As evidence of the university’s overindulgence, its critics pointed to Suzzallo’s salary, which he received in spite of the fact that the faculty was underpaid. Critics also pointed to the library, now nearing completion. It was extravagant, they claimed, for the university to use tax money to build that big empty room: what was needed was space to store books.

If Hartley could not get his superboard from the Legislature, he resolved to get it by gaining control of the various educational boards. The only resistance he encountered in this effort lay in Seattle. He overcame it in stages, first by filling in vacancies on the UW board of regents with his own men. A second opportunity came when he forbade the regents to spend the monies the legislature had appropriated over his veto. When the UW board voted to spend it anyway, the govemor dismissed two regents and replaced them with his supporters.

The massacre of the regents was done. On May 5, 1926. That evening, Hartley sought to head off the outcry by delivering a 90-minute tirade against educational “Waste and extravagance” to a crowd of 2,000 people in Seattle’s largest auditorium. Following the speech, a group of anti-Hartley people met at the Olympic Hotel to organize a recall campaign.

Hartley’s dismissals were challenged in court but ruled legal. In late May the governor attacked Suzzallo in an interview in Spokane. “Mr. Suzzallo does not know me. I was born in America and not Italy, and if they want to put the head of this state government at the University of Washington, all right. But until then it will remain at Olympia, one man will run it, and that will be me.” The “Dago Interview,” as it was dubbed, embarrassed Hartley. Editors also delighted in pointing out that Hartley had been born in Canada whereas Suzzallo had been born in California.

The UW regents meanwhile voted to keep the president for another year at the same salary. Then, in August, Hartley replaced another member, which gave him a majority. In September a dispute between the state and the University Alumni Association led Hartley to suspect that this body was being organized by Suzzallo as a quasi-political party to work against him, possibly in league with the recall movement. The war was now total. On October 4, 1926, the Hartley-dominated regents voted to demand Suzzallo’s resignation. He refused, and he was dismissed.

That evening, several faculty members gathered in the president’s house to plan the next move. Outside, 3,000 students demonstrated support and called for a strike if he were not reinstated. To quiet the situation, Suzzallo stepped out onto the porch, thanked the students for their support, and asked them not to strike. “I deeply appreciate your coming here tonight. I have devoted my life to the upbuilding of the university and I want you to devote your lives to it. Don’t do anything that will reflect discredit on your alma mater. If you are tempted to do anything that might injure the

university, I advise you to go to the front of our library building. Look up at it; That will be your inspiration to refrain from doing anything that might reflect on it.”

Suzzallo hoped that public outrage over his dismissal and the recall movement would work to reverse the regents’ action. But his battle with Hartley had reached the point where it was one he could not win. Well regarded as he was in academic circles, Suzzallo now had little public following. He could count on little support from organized labor, less from business, and real antagonism in the rural areas. Even among his own faculty, few came forward to help. According to the late Theresa McMahon, professor of economics at the university, a vote to support Suzzallo in a faculty meeting died for the lack of a second.

His dismissal, however, was not a personal disaster. Suzzallo became a kind of educational hero, especially in New York, where he was named chairman of the board of trustees and later president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. A 1927-28 trip to Europe became a triumph, during which he and his work were lavishly praised. More honors followed. In 1929, President Hoover named Suzzallo executive director of the National Advisory Committee on Education. His influence on the formation of public policy on education remained strong.

As fate would have it, it was on a trip in connection with his duties with the Carnegie Foundation that Suzzallo stopped in Seattle on September 18, 1933. He felt tired, and when his wife requested that he be examined by a physician, he was rushed to Seattle General Hospital. During the evening of September 24 he suffered a heart attack, and early the next morning he died. Eulogies were printed in newspapers and journals across the nation.

Roland Hartley survived the recall. Somewhat chastened by the experience, he was easily re-elected governor in 1928. If the library became Suzzallo’s monument, the massive capitol at Olympia was Hartley’s. It was an ironic one, given his loud denunciations of govemment expenditures, but one in which he took genuine pride. His second term in office coincided with the onset of the Great Depression, when his platitudinous bombast about individual initiative and the dangers of too much legislation eventually infuriated the electorate. He ran again in 1932 and was swept away in the Roosevelt landslide. A try in 1936—his sixth gubernatorial campaign—ended similarly. He retired from public life adamant, irascible, and forgotten. After he died in Seattle in 1952, his children ensured his anonymity by destroying his personal papers.

The real victim in the drama was the University of Washington, which Suzzallo’s dismissal left in shambles. The destruction of education in Washington was the subject of essays in The New York Times and The Nation, and the university became for years a pariah among schools. When a search was made for Suzzallo’s successor, no one of stature stepped forward, apparently not even Earnest Holland. The regents finally appointed Matthew Spencer, dean of the journalism department and a Hartley supporter. For eight years the university endured direct rule from the governors office. The faculty’s acceptance of the situation was eased by a comfortable pay raise, and most found Spencer a more approachable figure than Suzzallo. But the damage would last for decades.

During the Depression and World War II, the school concerned itself mostly with survival. While a few other premiere state universities were growing, assembling first-rate scholars and establishing their hold in the hearts of the state voters, the University of Washington was still recovering from the near-fatal blow Hartley had delivered. It is heartbreaking to consider what the school might have grown into without all those missed decades. In time, of course, it regained its aspirations, particularly with the arrival of Charles Odegaard; but then the catchup game ran into the periodic cutbacks imposed by the state’s economic cycles.

Perhaps Suzzallo had pushed too fast and too soon; perhaps he had foolishly neglected to build a base of support. But his visions and his contributions were not forgotten. After his death, the library that came to symbolize all those aspirations was named in his honor. In 1935, Bebb and Gould’s south wing was completed, and a modern concrete-and-glass addition finished the triangle in 1963.

And the work goes on. Just last week, the UW unveiled more details of plans for the massive final addition to the library, now one of the nation’s largest. There were a few faint echoes from the past. The new addition, by the distinguished national architect Edward Larabee Barnes will be costly and impressive—recalling the days when Suzzallo’s own architectural issues became a state issue. And included in the design is a small tower that evokes the memory of the bell tower that was to be the crowning element of Suzzallo’s library. The great bell tower itself was never to be built. It remains only an idea of what might have been.

news@seattleweekly.com