The day Donald Trump officially became President-elect, after a long and brutally divisive campaign, we had a nation split like never before.

And one group of people had a particularly tough job to do: Teachers.

At a time when anti-Trump protesters turned to the streets by the thousands, and even the pundits and pollsters and had gotten it wrong, classroom teachers were tasked with explaining to their students just how, exactly, someone who’d promised to deport immigrants, ban Muslims, and build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico, among other things, could have been elected to the country’s highest office.

We wanted to hear from them. We put the call out, and local teachers came back with their stories, and their students’ stories. Many students expressed raw fear over racist attacks, or the deportation of their family members, or their friends, or themselves. Many kids cried in disbelief. Many teachers did, too.

As one educator put it, “the day after the election was one of the hardest days in my twelve years as a teacher.”

But teachers do this job for a reason; their goal is to inspire, and to instill hope. So most of these letters end with resolve. “Now,” one wrote, “my real work begins.”

* * *

Wednesday morning I walked into my school completely emotionally drained. I worried about how I was going to hold it together for my students. I work in a school that is extremely diverse and has a high population of immigrants, students of color, and students who are homeless or facing severe poverty. Eighty-five percent of our students qualify for free or reduced lunches. There are over twenty different languages spoken by scholars and their families with the top languages being Vietnamese, Somali, Spanish, and Arabic.

Within the first five minutes of school I talked to a very worried student. He came up to me and asked, “Miss T., I’m Mexican. Does this mean that I’m going to Mexico? Is there really going to be a wall built?”

I hugged him and I told him not to worry, that there are checks and balances for people, even the president. But inside I was so emotionally sad for him and for the many immigrants at our school who are scared and worried.

Another student was worried because she’s Muslim and she came to me sobbing because she doesn’t want to be attacked because she wears a hijab.

It’s also noteworthy to expand on the “Trump Effect” — the increased violence, bullying and harassment — that has happened this year. This year, over and above all of my other 16 years of teaching, I’ve noticed more fights, bullying, and harassment than any other time in my career as an educator. I have heard a student from Mexico say that a classmate shouted at her to go back to Mexico.

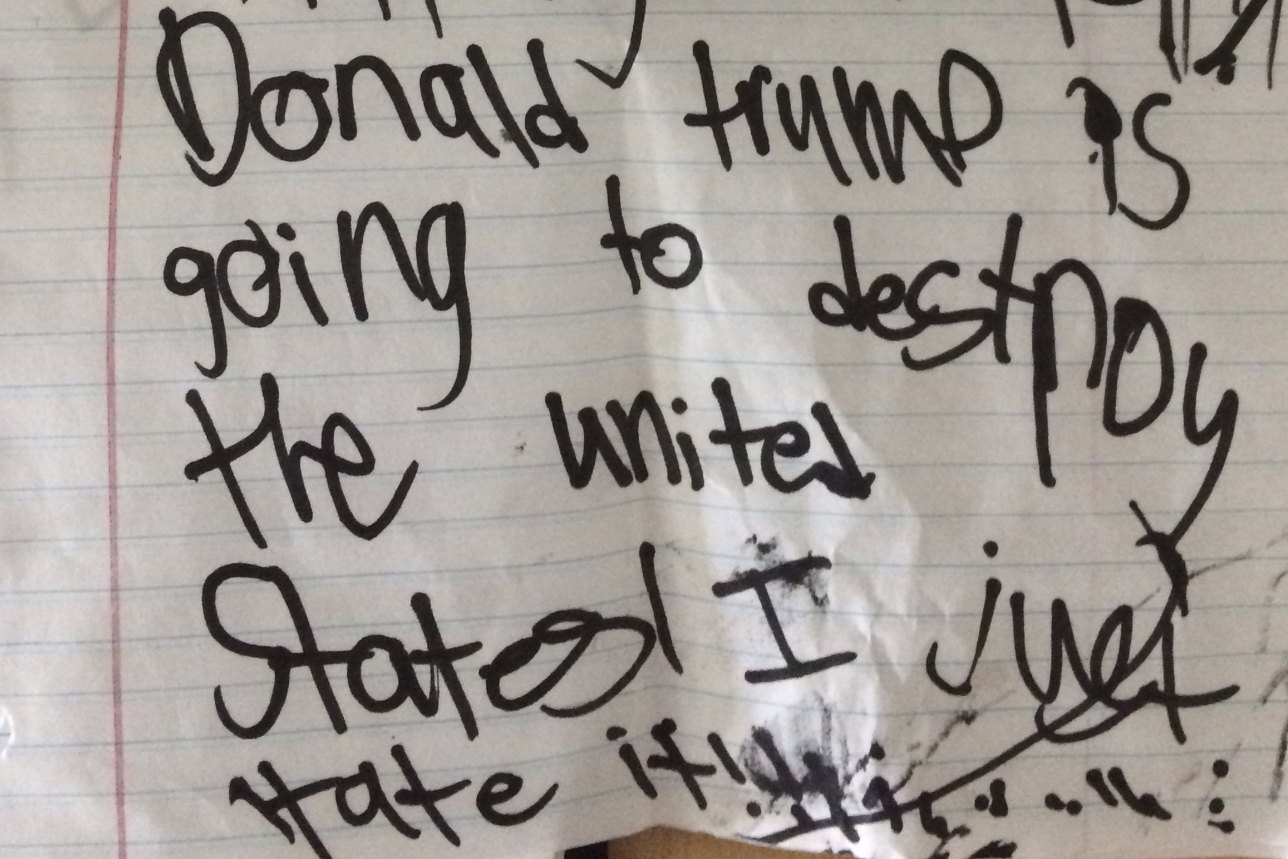

I’m including a photo that my fourth grade student wrote after sobbing in the counselor’s office [see above]. She is so worried about her safety and the safety of her family when Trump becomes president.

I am worried too.

—Karen in Renton

I teach 6th graders. I’ve been fielding questions about Trump since last school year. Most want to know what will happen to their families in a Trump presidency. They don’t understand how the law works, so they believe that even if they are citizens, they can be deported or jailed, especially my Muslim and Latino students. The day after the election, students came to school saying, “We’re all going to die,” “I’m moving back to (insert country of origin).” … The most disheartening reaction is when they look at me with teary eyes full of fear and simply ask, “How did this happen?” I had students who couldn’t even make it to school the next day because they were so scared and upset. I’m not talking about the students who look for any reason to miss school. These are some of my hardest working, highest achieving students. I think it hit them harder exactly because they tend to be more aware and mature than some of their peers and honestly see the potential damage this man can do in their lives.

—Tina in Seattle

The day after the election] was really, really difficult. Every one of my students is an immigrant, so you can imagine the feelings as they arrived in the morning. The heartbreaking part is they were trying to cope, making jokes about “packing their bags” and asking if I would go with them to Canada, Jordan, Mexico, etc. … one Muslim student said her mom had cried all night and couldn’t sleep. At that point I teared up, and instead of me comforting my students, they were lining up to hug me. How messed up is that? Muslim girls in hijabs lining up to hug an old white lady who could probably pass as a Trump supporter if I changed my hair.

—Abigail in Seattle

The day after the election was one of the hardest in my twelve years as a teacher. Many of my students are immigrants and/or their parents are immigrants. Their families have sacrificed so much to come in the United States and give their children the opportunity to study and pursue their dreams. Some are undocumented and left family, loved ones, violence, gangs and threats, travelled thousands of miles through treacherous situations and risked their lives to be here. They are strong, wise and incredibly resilient. These are some of their reactions to the election results.

“We are scared of how to protect our parents and relatives who don’t have papers.” “We are worried about how will take care of us if our parents are deported.” “We are worried about being deported to a place we haven’t been to since we were little children.” (In some cases, a place they fled for fear of violence.) “We are scared of a war between Trump supporters and those who oppose him.” “We are scared about how to comfort our younger siblings who are scared of what might happen to our families.”

Some were surprised that Trump was elected, but others have felt the racism in our country in such a personal way that they were not surprised. For many of my students, their fear was not as much about Trump, or even deportation, but the knowledge that so many people supported a person who made such racist and discriminatory statements. As a result, they are scared of being attacked or discriminated against because of their skin color. One student cried as she shared that it has taken so long for her to appreciate her skin color, because having brown skin has caused so much pain for her. Many of them feel extreme hopelessness for what is to come. They will graduate from high school in the next four years, and many are feeling their prospects diminish greatly.

These reactions are still very raw, but we are putting their emotions into action. We have begun writing letters to President-Elect Trump and anyone else who will read them. We continue to talk about how this is affecting each one of us, and how we can support each other. We will continue to stand together.

—Laura in Seattle

Two years ago I couldn’t figure out why my first grade student was so upset, why this hardworking kid wasn’t working. Later in the day I had to keep the tears back when I talked to their mom and found out her dad was in detention to be deported. Now it’s 2016. Monday, my 3rd grade students are leaving for the day. One stops and looks at me. “Is tomorrow election day?” “Yes, it is,” I replied. They covered their face with their hands and shook their head. “It is just too much pressure.” An 8-year-old telling me that the election is too much pressure. On Tuesday, as adults were casting their ballots, my students were at recess. I stood outside waiting for the whistle to blow. Two students, who had not been playing at recess, stood in front of me. “I don’t want to go back to where I came from,” the white student said. “I don’t think they should deport Mexicans, we are really good gardeners and that would be bad,” the brown student said. Eight-year-olds who should be playing basketball and tag are worrying about having to leave. They are worried about proving they should be in America. They can’t cast votes, they don’t have a say, they are powerless and relying on adults to build a future for them. Wednesday, my students entered the room. “I just don’t get it,” one said as they put their backpack away. Another student walked into the room, they came up to me and hung their head. “He won.” “I know. Do you need a hug?” As my class sat down to start our day, they discussed the winner of the election. When we talked about who won, one of my students raised their hand and said, “But what did the electoral college say?” My kids have faith in the system, they are scared but follow the rules. “Teacher, when I grow up I am going to be a judge first and then I’m going to run for President.” I can only hope that I will get to vote for them.

—Hannah in the North End

With my second graders, we talked about how lots of people are going to be saying lots of different things, some of them really mean and hateful and that although we may disagree or even agree with Donald Trump becoming our next president, our job was to be better, to keep on loving others and not use hate back. We talked about making positive change, using our words in a respectful way to say how we feel, and we talked about ways we could do that: going to college, making new laws, becoming the next president! Going to middle school and running for student president if they had one, telling people how we feel, continuing to make good decisions that we know of and accept others. One of my second graders cried and got really emotional because he thought he wouldn’t see his parents anymore after today. We comforted him as a class and our school community came together to support all students with conversations today.

—Deb in Seattle

I am a special education teacher in a resource room at an elementary school. I teach students with learning disabilities, language delays, health impairments and physical disabilities.

One of my students joined our school community last year at the beginning of his 3rd grade year. He didn’t know all of his letters and had extremely delayed language skills. He didn’t volunteer conversation and could answer questions with just one or two words. Over the course of the year, he threw himself into the slow and arduous job of learning to read, developing the pre-reading skills necessary to become literate. He is now in the fall of his fourth grade year, is beginning to read and to verbally express himself spontaneously.

The morning after the election, my three 4th grade boys walked in my classroom door for our reading time together. Immediately upon entering, one of the boys asked me, “When does Trump become president?” I answered, as nonchalantly as possible, “In January.” My other young man, the child who couldn’t put more than two or three words together when I first met him, walked up to me, looked me in the eye and said, “Trump is a racist. He hates black people and he hates Mexicans.” This boy is both. And my heart shattered. I had nothing to say, not because I actually had nothing to say, but because I couldn’t say, “Yes, honey, he is, and I am so sorry that this is who you now have to look up to.”

Because of his significant expressive and receptive language delays, I’m not entirely sure how to interpret his statement. I don’t know how worried this boy is about his future. I don’t know what he’s heard, his level of understanding about what he has heard, or any of the thoughts he might have about our current and coming situation. What I do know is that this boy, and so many like him, who are working so hard to succeed in life, on some level now know that they may very well have to work and fight so much harder for their basic rights. And I will keep dedicating my life to make sure they are ready for the fight.

—Amy in Shoreline

Wednesday, November 9th, was the hardest teaching day I’ve had since I started 5 years ago. It was harder than my first day. Harder than teaching through my divorce. Harder than trying to explain Sandy Hook. I work at an elementary school where about 50 percent of our students are Latino. I held back tears as I greeted my kids that morning. It was impossibly difficult to keep my composure as I fielded questions like, “Do I get to keep coming to this school?” and “How will I see my family when the wall is built?”

While adults struggle with anxiety in this time of great uncertainty, children are perhaps more vulnerable. I wanted more than anything to wrap them into my arms and tell them that everything will be OK. Instead, all I could do was tell them that world is still filled with good people who will keep fighting to do what’s right.

But, this week, I feel so helpless. Scarlet, one of my former students, has worked after school every day for three weeks on perfecting her performance of the Star Spangled Banner for the school’s Veteran’s Day Assembly. She is smart, hardworking, beautiful, and wise beyond her years. She also happens to be an undocumented immigrant.

On Thursday afternoon, Scarlet stood in front of her school and belted out our National Anthem great passion and pride. Students, teachers and parents watched with hands on their hearts and tears in their eyes.

When I told Scarlet I was writing a story for the Seattle Weekly, I asked her if there was something she wanted to share with its readers. Scarlet told me that she had planned on being the first member of her family to graduate from high school. She told me how hard her mother works day and night and how she can’t look at her mom’s tired face without crying. Like every other American, she talked about making a better life for her family when she grows up. But, now she worries that she will not have the chance to change things for the better if Trump deports her and her family.

Things have started to calm down, most of their outright panic has made way for deep sadness and real, lingering fear. Now my real work begins. I feel more compelled than ever to teach my students kindness, acceptance, love, and that knowledge can empower.

—Kelly in Renton

Students were shocked. During classroom discussions they shared fears, asked questions, some cried, and, at the end of class, we took a moment to share our collective hopes and commitment to be in solidarity and stand up for one another and every member of our community. I spent the day with students that requested one-on-one opportunities to share their individual fears of being deported, committing suicide before their families could be separated, and wanting to fight as a method of processing their anger. In each class and conversation we ended with vows of solidarity and a validation of the students’ life and celebration of their family heritage and culture. Before the end of the school day, one student wrote, “I hope I can make people smile again.”

—Sandra in Seattle

Wednesday morning, I was grieving, big time; the tears would not stop. I was unsure of how I would approach my class, but it is my job and I knew I would, somehow find a way. The questions asked by my 8- and 9-year-olds were ones about how the popular vote could lose? What an electoral college is? By far the most heartbreaking question on everyone’s mind was, are some of my friends going to have to move away? I did my best to keep it together, to remind my student that there are laws upheld by our government that will not allow one man to overturn the country. That in many election past, promises were made that could not be fulfilled because of our laws. I taught me kids about the electoral college and try my best to explain why the popular vote can and often does win. I have a very diverse classroom and so the yes my kids are scared. They have been following the words of Trump since last spring. They have heard their parents speaking, they listen to the media and they are frightened.

My message was to be the light. That when others go low, we go high. That sometime having hateful feeling dims our light and that we need to shine our lights even brighter to help them see the truth through love and compassion. My kids love metaphors. I explained that hate comes from fear, fear of what we don’t know; and that by sharing ourselves we share our light and only love can grow from there.

—Shelly in Seattle

Names have been changed to protect teachers’ and students’ privacy.