DEATH IS KIND to those we romanticize in myth, particularly when they perish young, handsome, and bravely on the slopes of a mountain. The fatal 1996 storm of Into Thin Air and last year’s discovery of the corpse of George Mallory on the north side of Everest have sparked renewed interest in the Brit who may or may not have been first to scale the world’s highest peak in 1924. Last year saw the publication of three books arising from the expedition that found his frozen body (offensively splashed on the cover of Outside). However, while Ghosts of Everest, The Lost Explorer, and Last Climb were preoccupied with the “did he or didn’t he?” question, The Wildest Dream concentrates more on the man.

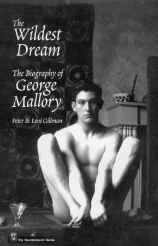

THE WILDEST DREAM

by Peter and Leni Gillman (Mountaineers Books, $27.95)

Cascade Alpine Guide I, Third Edition

by Fred Beckey (Mountaineers Books, $34.95)

Stone Palaces

by Geof Childs (Mountaineers Books $22.95)

Relying extensively on private letters and cooperative family members, Dream is a necessarily short biography of a short-lived subject (1886-1924). We learn how the bright, athletic son of a country vicar displayed an early knack for scaling walls and trees. Owing to his parents’ imperfect but sketchily detailed marriage, however, the authors conclude: “It was thus not surprising that George should acquire a taste for risk.” That bald and unsupportable conclusion betrays the modern tendency towards patho-biography—in other words, every adult achievement is rooted in some early trauma or malady. Did young George’s “semidysfunctional family” not provide enough love? Did he excel to gain the childhood attention he never received? Boo hoo.

The fact is that Mallory was a standout athlete at Cambridge, became a pioneering climber in the Alps and Scottish Highlands, stood as a fringe figure to the Bloomsbury Group, and survived WWI—all before he first glimpsed Everest in 1921 (the first of three expeditions he undertook). The authors, both experienced mountaineering writers, do a good job of detailing Mallory’s youthful accomplishments and milieu—reminiscent of Brideshead Revisited with its upper-crusty homoeroticism. There’s evidence that George had a brief sexual relationship with the brother of Lytton Strachy (the latter was portrayed by Jonathan Pryce in Carrington), unsurprising given the mores of the day. The authors of Dream don’t want to deal with the notion that sexuality is a social construct, but Mallory’s one gay encounter seems to have been his last, as he soon entered a happy heterosexual marriage. (Then again, so did many other of his quote-unquote gay contemporaries.)

So why—after two arduous, unsuccessful expeditions—did he leave his wife and three kids to try Everest the last time? Mallory acknowledged what he called “my personal ambitions” and what a friend termed “the label of Everest.” He could make more money on the lecture circuit than as an ill-paid teacher. It was on one such tour that his famous “because it is there” remark was made. But with more fatalism, he also admitted alpinists climbed “because we can’t help it.”

Whatever the rationale for his fateful endeavor, Dream usefully supplements two prior Mallory bios (the most recent dating to 1969) with often-touching personal detail. The facsimile of a water-stained letter he wrote to his daughters from the 1922 expedition movingly attests to his reluctant separation from family. Two years later he would write, “It is 50 to 1 against” summiting in the “world of snow and vanishing hopes” in which he was last seen alive, ascending.

TWO LOCAL AUTHORS reflect a different side of mountaineering, particularly in the third edition of the Cascade Alpine Guide 1 by Northwest climbing legend Fred Beckey. Now 79 years old, he’s revised his indispensable volume—covering the region between the Columbia and Stevens Pass—for the first time since 1987. During his storied career (less romantic than pragmatic, as compared to Mallory’s), he’s accomplished much, but the sport of climbing has changed much, too. With countless first ascents in once-remote areas to his credit, Beckey is now writing for a new generation of 5.10 gym climbers unwilling—or unable—to endure the long, tough, brushy approaches; loose gullies; and sketchy conditions that are the hallmarks of a Beckey route.

As a result, few weekend warriors will attempt the south rib of the southeast face of Garfield, but at least CAG 1 has considerably updated its approach descriptions—allowing one to find more accessible routes without getting hopelessly lost on old logging roads. Other guidebooks offer more detailed descriptions of the most popular climbs, but nothing matches CAG‘s comprehensiveness. As for his ratings for the South Cascade classics . . . well, the west ridge of Stuart is admittedly only 5.4, but his typically terse “exposed, athletic, yet seldom hard” doesn’t quite convey the feel of a route that has had many climbers—this one included—descending at night. But we can’t all be Beckeys.

Such modesty emerges from the better chapters of Mazama writer Geof Childs’ Stone Palaces. His compendium of magazine pieces and essays is a mixed bag at best, with the humor and short story-like efforts lacking. Writing about specific climbs and climbers—without the pot haze philosophizing—is his stronger suit. An autobiography would’ve been a better vehicle for unifying his stories, but the present mountain-literature market is for disasters and Everest veterans—which unfortunately excludes both Beckey and Childs.

Peter Gillman will make local lecture and signing appearances 10/21 (Northwest Bookfest), 10/26 (Third Place Books), and 10/27 (Eagle Harbor Books on Bainbridge Island).