On a brisk Saturday morning at Cal Anderson Park, Emilia Allard and Rhiannon Rasaretnam huddled underneath a white tent as they finalized the logistics of the day’s events. While their project was education-based, it wasn’t meant to earn credits for graduation. In fact, they attend different King County schools and only met a month ago. Similar to many youth around the country, they considered taking action following the fatal shooting of 17 people in Parkland, Fla. last month a matter of life or death. No longer would they leave their safety up to chance like a game of Russian Roulette.

Shortly after 10 a.m., Allard and Rasaretnam strode up the stage’s side stairs with the usual briskness of 17 year olds. They positioned themselves at the podium and greeted the cheering crowd with a look of austerity usually reserved for people twice their age. The look of people who have finally had enough.

Behind them, colorful posters bearing words such as “ban assault weapons” and “protect kids, not guns” adorned a fence that gave way to an overflow section filled with hundreds of people who couldn’t fit on the field.

“On the day of the Parkland shooting, I remember walking into one of my classrooms and I glanced down at my phone,” Allard, a Ballard High School senior, started her speech as she surveyed the thousands of people packed onto the field. Her red hair was pulled into a tight bun, and she wore a blue hoodie that read “March for Our Lives.” She recalled looking at a Facebook notification about the school shooting on Feb. 14, but it hardly phased her. “The only thought that I had at that point was, ‘How many people died this time?’ And then I just turned my phone off and put it back in my pocket, and went to class as if nothing unusual had happened.” Allard and her classmates have grown desensitized to active shooter drills in schools and news about youth dying by gun violence, since they have always lived in a post-Columbine world.

But this time, something clicked for her. Allard went home after hearing news of the Parkland shooting to talk with her family about what she and her five school-age siblings would do if they encountered an active shooter. Allard expressed concern for her younger sister Charlotte, whose autism might prevent her from remaining quiet while she was in hiding. “For Charlotte, that means that she would be posing not only a risk to herself, but to those other 25 kids in that classroom. And for me, that was sort of the turning point where I knew that I had to…” Allard’s voice cracked as she choked back tears, and cut her sentence short. A wave of applause and whoos from the audience beckoned her to continue. “And so that was when I realized that I had to get involved not only for myself, and for my family and my peers, but for Charlotte and for kids like Charlotte.”

Just as Allard was spurred into action, Tahoma High School senior, Rasaretnam, was having similar thoughts of her own. Rasaretnam felt “angry, but apathetic” after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, but was empowered to see the school’s survivors take action.

In the wake of the shooting, student activists spearheaded the March for Our Lives demonstration in Washington, D.C. to urge politicians to pass stricter gun control laws and to make schools safer. Seattle’s March for Our Lives—started by Allard and Rhiannon once they realized that they had both started separate social media pages for a local version—was one of over 800 similar marches throughout the country on March 24. Just as social media helped elevate the voices of the Parkland shooting survivors, it was also instrumental in helping Seattle’s youth collaborate and plan.

Along with Rasaretnam and Allard, a core group of a couple dozen high school students from throughout Washington organized through social media to plan logistics. As of Saturday evening, they had raised over $40,000 of a $60,000 GoFundMe goal to pay for the event’s security and permits. After school last Thursday, they held a sign-making event at Capitol Hill’s Cupcake Royale.

They were working tirelessly up until the night before the event, when many of them stayed in a hotel near Cal Anderson Park to finish making posters and finalize their speeches until 3 a.m. It was like a “work slumber party, without a lot of slumber,” Bothell High School senior Kyler Parris told Seattle Weekly shortly before running onto stage.

Although they had different reasons for organizing, all the students agreed that it was crucial to end the daily shootings of 46 children and teens, according to Brady Campaign To Prevent Gun Violence. They also believe in the significance of increasing youth voter turnout to help pass tighter gun control legislation.

The day before the National School Walkout on March 14, Rasaretnam and Allard were the key speakers at a Seattle Indivisible anti-gun violence rally, where they expressed their dissatisfaction with the current political climate.

“The elected officials have let us down,” Rasaretnam said to about 20 mostly middle-aged people who held signs that stated “#NeverAgain” outside of downtown’s Henry M. Jackson Federal Building. Rasaretnam’s dark hair with dyed blonde tips was pulled back in a ponytail, and she wore a maroon windbreaker. “We will no longer let our elected officials risk our lives because of the influence of organizations like the NRA. We will hold them accountable when we show up to the polls in November.”

At the March for Our Lives demonstration two weeks later, Rasaretnam reiterated many of the demands that she had grown accustomed to shouting over the past month. She and other youth speakers listed call to actions that included banning the sale of assault and semi-automatic rifles, as well as accessories designed to increase a gun’s rate of fire. With bigwigs like State Attorney General Bob Ferguson and Gov. Jay Inslee in attendance, they urged politicians to raise the age to own a firearm in Washington state from 18 to 21 years old, and to end private gun sale loopholes.

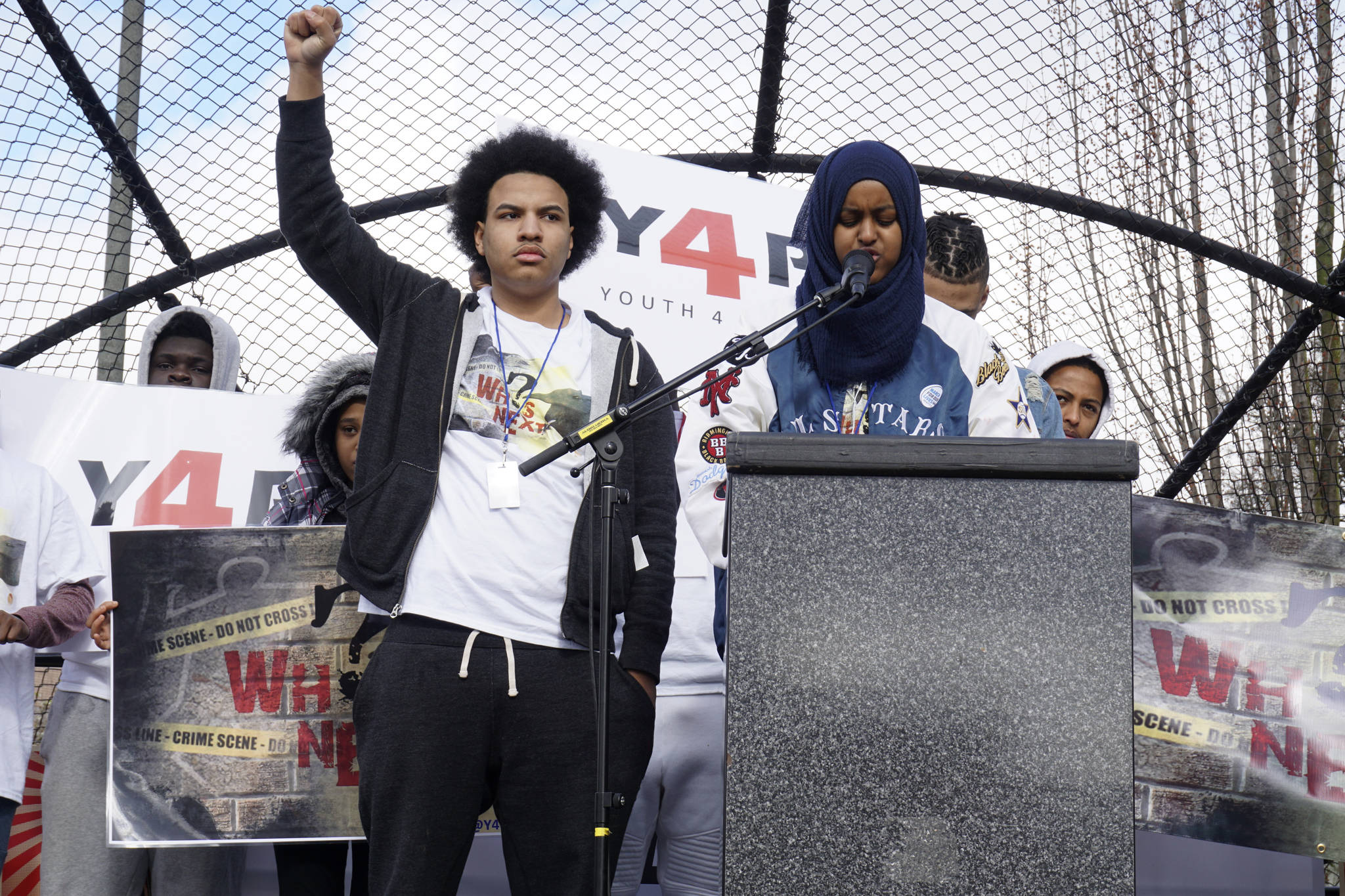

After Rasaretnam spoke, members from youth advocacy group Youth 4 Peace took the stage to share their experiences as students of color who are disproportionately impacted by gun violence. Member Elijah Lewis, a Rainier Beach High School senior, read the names of people in Seattle who had been killed by gun violence. As he spoke, other teenagers on stage took turns placing stems of roses on the ground in remembrance of each victim, until Lewis rattled off more names than there were flowers to throw. He wore a sweater emblazoned with a picture of his deceased brother on the back, his hands held in prayer. Lewis emphasized that he didn’t believe that teachers should be armed with guns, because he already felt targeted in school by staff who considered him a threat as a black man. “So I know that a teacher probably already would have shot me,” he lamented.

As the march commenced, marchers that Seattle Weekly spoke to concurred that teachers should not be armed to protest students, as President Donald Trump suggested following the Parkland shooting. Holly Tyra, a Kindergarten physical education teacher and creative director at Sweet Pea Cottage Preschool of the Arts, said it was “ridiculous” that teachers should be expected to carry guns. She wore a sign strapped to her back that had iridescent blue balloon letters that spelled out “Enough.”

“We’re teachers, and we’re pissed and we’re going to stand behind our students,” Tyra said as chants like “Hey hey, ho ho, NRA has got to go” swirled around her.

But not everyone at the march agreed with the anti-NRA sentiment. Towards the end of the demonstration, one counter-protester wearing a camouflage hat and coat silently marched with a wooden cross. One of two posters stapled to the cross read, “Guns are not the problem. Lack of Jesus is!!” The other poster stated: “The NRA=Protection. Bad guys with guns are stopped by good guys with guns!” The core organizers at the helm of the march stopped as they approached him, and called for everyone to link arms. A few students ran ahead of the group to place their posters over his, covering the messages from view.

The groundswell of youth activism moved older generations to get involved in protesting gun violence. Although March for Our Lives was student-led, some of the organizers’ parents supported them by hosting event planning parties at their houses and joining them at the event. Corry Parris, organizer Kyler Parris’s father, is a professional photographer who has documented the students’ actions over the past month. But he’s chosen to stay on the sidelines, “because it’s their thing, not mine,” Parris told Seattle Weekly during a phone interview. “It inspires optimism in me, because the people my age did not do a lot of this social activism, at least not on the scale that the kids are doing it now.”

And according to the organizers, they’re not planning on stopping anytime soon. Although many of them are first-time activists, the students said they plan to continue the momentum from Saturday’s march by raising attention to related issues. March for Our Lives spokesperson Katalia Alexander, an 18-year-old Mount Senior High School senior, said that the organizers want to address systemic racism, and to stand with communities of color that are disproportionately affected by gun violence.

Alexander sees voting as the next step that will help organizers sustain Saturday’s message. “Voting is probably the most important and effective way to make your voice heard in our political system,” she said. “We will vote for politicians who will represent us and work towards comprehensive gun legislation on a state and a national level. And who knows? Someday soon you’ll probably see some of us running for office.”