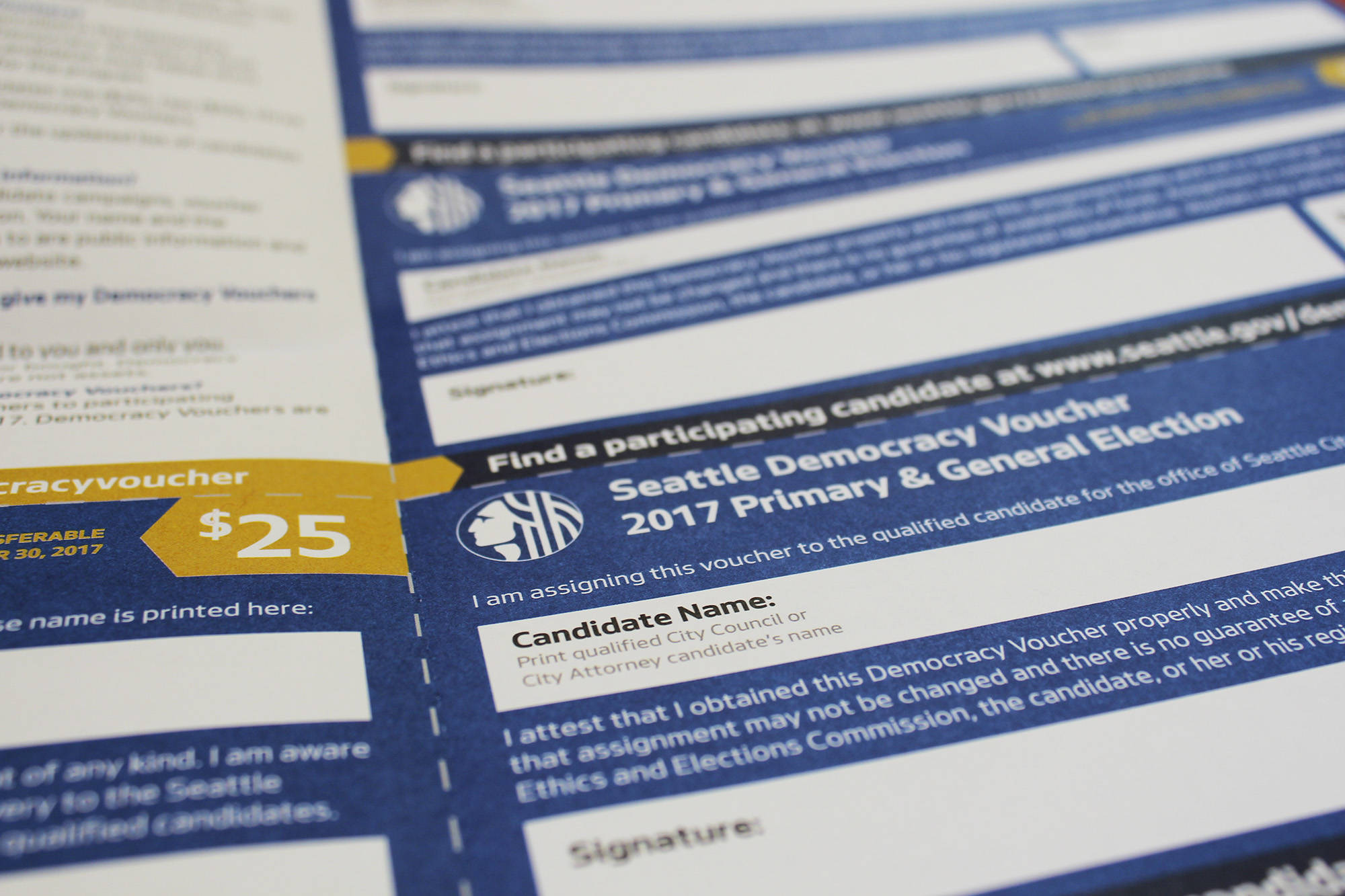

A lawsuit filed Wednesday on behalf of two Seattle homeowners asserts that Seattle’s Democracy Voucher program, passed as a citizen-led initiative in November 2015, violates the free speech rights of property owners, who fund the program through a property tax. The tax costs the average homeowner in Seattle about $11.50 per year and that money goes toward giving Seattle residents four $25-dollar certificates that they can put toward candidates of their choosing.

The program is thought to be a way to level the political playing field by enabling ordinary voters to fund campaigns—and thus get powerful special-interest money out of elections. It’s the first program of its kind in the nation. The Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF), a limited-government nonprofit organization, argues that this isn’t democracy at all; it’s “coercion.”

“The so-called ‘democracy vouchers’ could not be more undemocratic or unconstitutional,” said PLF attorney Ethan Blevins in a statement about the lawsuit filed Wednesday in King County Superior Court. “You can’t be forced to engage in political expression or advocacy that is contrary to your convictions. … The voucher tax conscripts property owners into footing the bill for other people’s donations. It forces them to fund contributions, candidates, and causes they might not favor.”

So far, the candidate who’s raised the most money with the program is tenants’-rights activist Jon Grant, who is running for City Council Position 8. As of June 26, Grant had raised $128,750 in vouchers alone, according to the latest numbers from the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission.

In the lawsuit, PLF attorneys call this out, specifically.

“Jon Grant—a housing advocate and former head of the Tenants Union of Washington State—has received more compelled campaign contributions than the other two candidates combined,” the complaint reads. “If elected, Mr. Grant promises, among other things, to grant renters collective bargaining rights, a proposal that will affect the political and economic interests of Seattle’s landlords. He has vowed to ‘freeze all permits, licenses, and rental registrations where the landlord has any ownership stake until they meet and negotiate in good faith with the tenants.’ [The voucher program] forces landlords and other property owners to sponsor these messages.”

To Grant, this is hardly an insult. “I’m so flattered!” he jokes. “I feel like I’m doing something right.” He confirms that not only has his campaign received more Democracy Vouchers than the two other candidates who are participating in the program — City Attorney Pete Holmes and Position 8 candidate Teresa Mosqueda — but over 90 percent of all of his campaign’s donations come from the vouchers. He was the first candidate to get qualified for the program.

“I think that the lawsuit is not at all in synch with the values of Seattle,” Grant says, pointing out that the the initiative passed in 2015 with a clear majority — 63 percent of the vote. “I think that this is a program that has wide support.”

According to Grant, it also has support from homeowners. “I’m going door to door,” he says, and “many times I’m talking to homeowners. The homeowners I talk to are thrilled about this program. It gives them a voice in the political process where there was none before.” Although home ownership is a high bar in Seattle these days, it’s really the uber-wealthy, Grant argues, who are donating to political campaigns; there are middle-class and working-class families who own homes, too. “It levels the playing field for those folks.”

It can also theoretically level the playing field for people without homes at all. A few months ago, Grant’s campaign announced that it aimed to enroll homeless Seattleites in the Democracy Voucher program. He says now that he and his team had some success with that, though it became difficult to follow up with the people they’d worked with given the city’s continual homeless sweeps.

The point being: Any Seattle resident can use the vouchers to fund the candidate of their choice. Still, one of the PLF lawsuit’s plaintiffs, Sarah Pynchon, can’t. Although she owns and rents out a single-family home in Seattle, she doesn’t live in Seattle; she therefore pays for a program she can’t participate in. “Further, the program is effectively asking me to fund candidates that I may not agree with,” Pynchon said in a statement. “Indeed, as currently structured, the vouchers could be used to elect people who will continue to put financial burdens on outnumbered property owners, a form of taxation without representation.”

To Grant, PLF “is trying to mince issues here. The reality is the city has every legal right to pass a tax on property owners to pay for its programs. We have a property tax that same person has to pay for affordable housing, for supporting our public education programs … these are all programs she does not directly benefit from.”

He adds that this is not the first time PLF has sued the City of Seattle over housing laws, or in support of homeowners. “It’s no surprise to me that they’re very worried about my candidacy, and the things I could do to protect tenants” if elected, he says. “To them, our campaign is a real threat.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com