Civic scandals used to mean something in Seattle. Gunslinger Wyatt Earp paid off City Hall to operate his 1890s gambling joint here. In the 1950s, bar owners were leaving lunch bags of money on their counters for beat cops who threatened to shut them down if they didn’t. A half-century later, aging mobster Frank Colacurcio did what he could to keep corruption alive with a political payoff scandal known as Strippergate. Though Colacurcio was later indicted for racketeering and prostitution, he beat that rap this year with a sure-fire defense: sudden death.

Alas, what passes for scandal today is a city council member rudely signing a piece of paper that the mayor was supposed to sign, but wouldn’t. The dust-up did have an underworld aspect—it had to do with Seattle’s proposed car tunnel—and conflicted with the mayor’s personal vice: a perverse fondness for bicycles. But it was a pitiful turn for a city with such a rich history of shame, dishonesty, and corruption. Our cops used to row people out to the middle of Lake Washington with large metal balls clamped around their necks, and tell them to swim back—or talk. We endured gangland murders and car bombings, and had a steady daisy chain of bribes, kickbacks, and payoffs moving up through the police department to the top floors of City Hall.

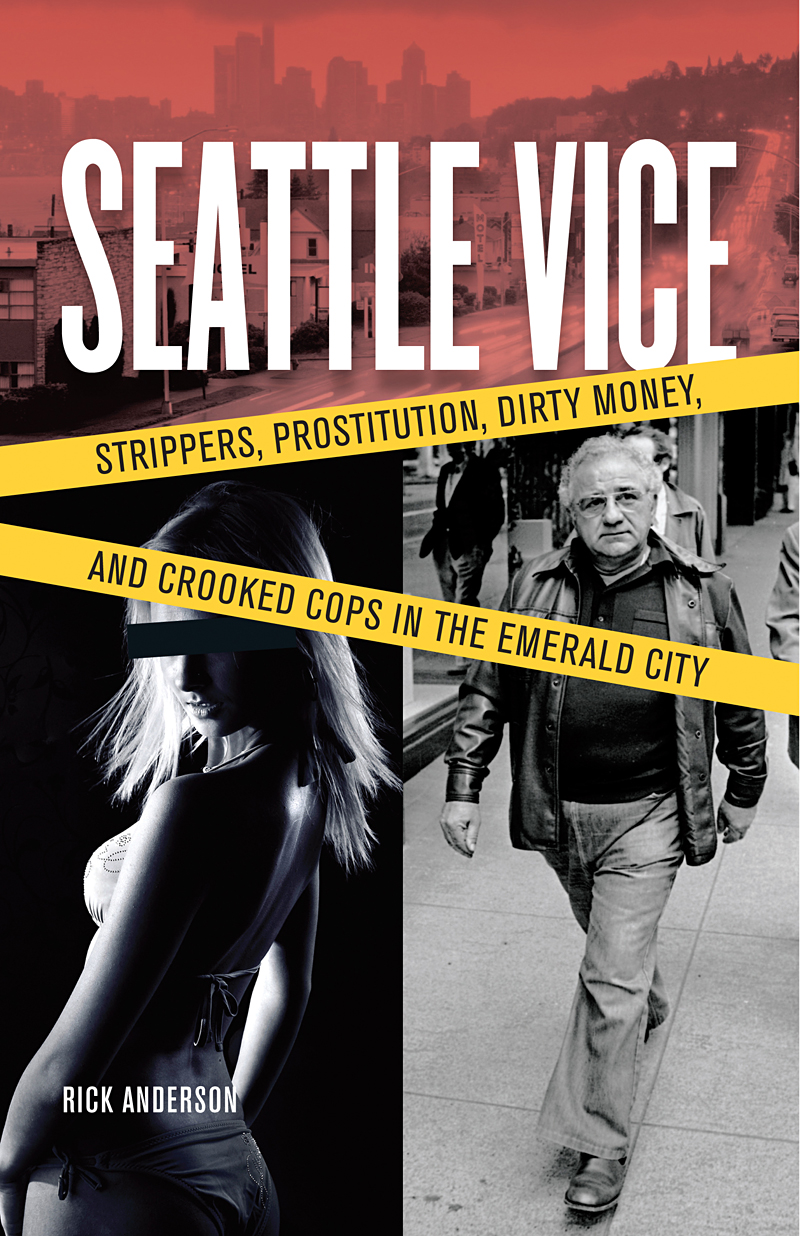

As detailed in my new book Seattle Vice (Sasquatch Books, $17.95, out Nov. 1), which is excerpted here, we once had the kind of corruption worth bragging about. And for a good part of a century, it was accepted and expected. As Colacurcio observed, “You go with the flow.” And in Seattle sex, violence, and dirty money began flowing about 120 years ago. RICK ANDERSON

==========

The recorded legacy of Seattle vice and corruption reaches back to saloon impresario John Considine, who helped introduce Seattle to drinks, debauchery, and a risqué belly dancer named Little Egypt in the late 19th century. He memorably battled rival Alexander Pantages for Seattle’s vaudeville turf, with both men stealing each other’s acts and rising to eventual fame in Hollywood: Considine as a silent-film producer and head of an acting family, and Pantages as a movie mogul and theater-chain owner.

But it was Considine’s hidden payments to beat officers that made lesser-known history, ranking among some of Seattle’s first street-level bribes. Just as a Colacurcio would do half a century later while dominating his era’s vices, Considine offered cops cash to look the other way as he violated Seattle’s sin laws. Among the statutes he paid to break was the 1894 “barmaid ordinance.” The law prevented women from working where alcohol was served, and Considine clearly needed them at his People’s Theater, in what is now Pioneer Square. The “box-house” saloon and card room featured female performers who danced, sang, and serviced a willing crowd, mostly lusty prospectors who spilled into town during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Considine also ran three illegal betting parlors by paying fines and bribing cops under a vice-tolerance policy that would appear, disappear, and reappear in Seattle throughout the next century. His cozy relationship with Seattle Police Chief C. S. Reed allowed him to monopolize the action for a few years until competitors, some formidable, bought in. Among them was gunslinger Wyatt Earp, described in 1899—18 years after the gunfight at the O.K. Corral—by the Seattle Star (a racy Seattle Post-Intelligencer rival that folded in 1947) as “a man of great reputation among the toughs and criminals, inasmuch as he formerly walked the streets of a rough frontier mining town with big pistols stuck in his belt, spurs on his boots and a devil-may-care expression upon his official face.” His Union Club betting parlor and saloon at First Avenue and Union Street thrived for more than a year until a citywide crackdown on gambling drove him to San Francisco.

Only months after Earp departed, Considine’s joints reopened. He didn’t get along as well with the next police chief, so he killed him. In a 1901 showdown, Considine shot the dislikable William Meredith three times after the chief fired at him first, his bullet described in one news report as “scraping along the back of Considine’s neck and lodging in the arm of a messenger boy having sarsaparilla at a soda fountain.” Considine’s actions were deemed self-defense by a jury that took just three hours to decide they didn’t like Meredith either.

The police payoff system continued under Charles “Wappy” Wappenstein, Seattle’s head cop from 1906 to 1907. He became security chief at Seattle’s first World’s Fair, the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, held where the University of Washington now stands. He was reappointed chief in 1910 by new mayor Hiram Gill, an early believer in tolerance policies, if not outright corruption. Wappenstein immediately informed the madams of Seattle’s thriving brothels that they each owed $10 per harlot per month, payable to him or his beat officers.

Wappenstein had everything under control. Mayor Gill didn’t. He left town for a pleasure trip one day, and an acting mayor quickly formed a committee to investigate Seattle’s vice. The P-I also investigated and spread the word about City Hall corruption—just as it would again 50 years later, exposing yet another regime of cops and politicians who “tolerated” vice in return for bribes and kickbacks. Gill was tossed out of office by voters in a 1911 recall. The deciding ballots came from women whose right to vote—briefly granted, then taken away in 1887—had only recently been restored. Wappenstein also lost his job, and was indicted by a grand jury.

When not on the take, cops were on the give, dishing out punishment not only to the guilty but to the merely accused. Getting someone to confess to a crime simply meant putting them in a rowboat with an iron ball chained to their neck and riding them out onto the water. They could either talk or “accidentally” be thrown overboard. That was the procedure according to William Severyns, Seattle’s police chief from 1922 to 1926.

In his autobiography, Confessions of a Chief of Police, Severyns, known as “Mad Dog,” revealed how cops multitasked with the iron ball. They could balance it over a prisoner’s head, attached to a cord threaded through a cell door and tied to the prisoner’s raised leg. If he didn’t confess and grew weary from questioning, his leg would give way and the ball would skull him.

Police also used the “Electric Carpet,” a live-wire mat that sent shocks, triggered by an interrogator, to any suspect thought to be lying. “In using this,” Severyns cautioned, “the prisoner is placed in a cell far removed from others, so his screams cannot be heard.”

In 1964, Seattle mayor J. D. “Dorm” Braman revived a city tolerance policy that had lived through the ’50s, then faded under political pressure. Braman had been supported by high-rolling operators of gaming clubs and took up their cause in office, restating the notion that vice was easier to police if it was licensed and regulated.

So how was the new policy working? Much like the old one, as Seattle began to learn in 1967 from a series in The Seattle Times by John Wilson and Marshall Wilson. Known as the Wilson twins, though not related, they spoke with Skid Road and First Avenue tavern operators who claimed they were being forced to make payoffs to police. The Wilsons kept low to the ground, spying on the cops as they made cash pickups, although the cops spied them as well: While the Wilsons sat in their car on a stakeout one night, John’s coat sleeve caught on a steering-wheel ring and set off the car horn, causing a couple of cops to notice and quickly move away.

The “twins” nonetheless determined that payoffs were widespread. Their series also revealed how on-duty officers whiled away the hours in one First Avenue tavern, gambling after hours. Unreported then, but years later confirmed by a bar operator, police also used to take over Swannie’s, the Pioneer Square eatery and home of the Comedy Underground, for after-hours target practice, using live rounds to shoot beer bottles and other objects set atop a high ledge on the back bar.

As the Wilsons would write in a follow-up story, however, “Official reaction was more of indignation than of concern.” Police Chief Frank Ramon expressed shock at the series, but played it down as misconduct among a few officers. Mayor Braman, a onetime lumber and hardware dealer, said he was interested in “building a better city” and less interested in running the police department. He formed a committee to investigate, but gave it no powers. After studying the issue, the committee found nothing to justify criminal charges.

The P-I also came up with a rollicking exposé later that year: a long series of stories by ace reporter Orman Vertrees, who noted that public officials claimed the tolerance system keeps out “Chicago gangsters” and other mobs, while critics wondered if it truly was just a guise to allow local gangsters to lock up control of the multimillion-dollar vice industry. His story cited previously unreleased federal documents claiming a Seattle coin-machine trade group was formed to restrain trade and fix prices.

The weeklong series in November 1967, along with follow-up stories, documented payoffs and tax cheating in the pinball industry; it also coughed up some new details about Seattle’s favorite suspected racketeer, Frank Colacurcio, who was quietly building what looked like a regional empire of vice. He’d bought into five historic Washington hotels in Centralia, Wenatchee, Mount Vernon, Port Angeles, and Aberdeen, where his brother Patrick was in charge at the Morck Hotel, thought to have become a haven for prostitution.

The P-I also zeroed in on how innocent bingo games were turning big profits for their operators, some of them tied to Colacurcio. Pensioners were being victimized by games that were supposedly run as charities, but were earning some operators up to $320,000 a year, the paper said. The biggest offender seemed to be a man named Charles Berger, who did time at McNeil Island (then Federal) Penitentiary for tax evasion, and who ran the Lifeline Club in a large second-floor room at Pike Place Market. Berger’s club was up the street from another parlor called ALFA (Assisting Legislation for Aging), run by a man named Harry Hoffman.

Both parlors featured bingo at a dime a card, which were thrown away after each game. The gamers were predominately housewives and the elderly, spending a few bucks or so on cards, but rarely at a profit. To illustrate the futility of trying to win at the clubs, a P-I undercover bingo player lost $395 while winning only $55 in a four-month spree. The paper also gave its agents money to go into card rooms, where they also lost badly—and discovered some card decks were being marked.

Though not well known, among the P-I‘s losing amateur agents was Vertrees’ brother-in-law, a young man named Mike Lowry. He played cards on the paper’s tab, and was quite poor at it. He went on to become a congressman, and in 1992 was subsequently elected Washington’s governor.

“I went in and played cards in the back room of one of those places,” Lowry said in a interview for this book. “I wasn’t even in their league. But then I think that was the plan. What good would the story have been if we all won?”

By 1968, both the Times and P-I were steadily reporting on widespread corruption, the protection racket, and the booming bookmaking industry, also linking longtime King County prosecutor Charles O. “Chuck” Carroll to gambling and determining pinball alone was bringing in $5 million a year to the industry.

Seattle magazine profiled Carroll as well, questioning his judicial tactics, depicting him as a vengeful prosecutor who held out for harsh treatment for blacks, and calling for his resignation. The P-I memorably provided its readers with photographic evidence, grainy as it was, showing county pinball kingpin Ben Cichy allegedly delivering money to prosecutor Carroll’s home. Cichy headed Farwest Novelty Co., which held the master license to operate 1,540 county pinball machines, pool tables, and bowling games in local taverns. Thanks to a legal opinion by Carroll that gaming was allowed despite some conflicting laws, a county tolerance policy quietly flourished outside Seattle, to Cichy’s profit and delight.

Reporter Vertrees, noting that Cichy and Carroll were “on opposite sides of the fence of life,” wrote that the two had been having regular monthly meet-ups. “What could possibly be the nature of such liaison between men of such diverse callings,” Vertrees asked in print, “a prosecutor and a pillar of the pinball fellowships?”

P-I columnist Joel Connelly well remembers that sneaky Cichy photo, taken by the paper’s Dave Potts, who hung out on a nearby balcony night after night to snap the pic. “I saw it when I was young,” Connelly says. “I was amazed at what it meant. That’s when I knew I wanted to be a newspaperman.” State attorney general John J. O’Connell brought in Ralph Salerno, former supervisor of the New York Police Department’s detectives, to consult with investigators, saying he knew of no other major U.S. city with a gambling-tolerant police force approaching Seattle’s. Editorialists and letter writers demanded an investigation.

As the pressure increased for a widespread probe into who was paying whom, Cichy, on May 30, 1969, conveniently drowned off the dock of his home in Yarrow Point. Foul play was suspected, yet never proved. He was an excellent swimmer found in five feet of water.

Mayor Braman had resigned a few months earlier to accept an appointment as a U.S. Department of Transportation assistant secretary in the Nixon administration, and was replaced by interim mayor Floyd Miller, a city council member hoping to clean a little house. He handed limited power to three assistant police chiefs—Frank Moore, George Fuller, and A. C. “Tony” Gustin—to clean up the department. In that spirit, Gustin and Fuller backed what turned out to be a historic September 24, 1969, raid on the Lifeline Club without telling Chief Ramon in advance. When Ramon left town on a brief vacation, Gustin and his squad swooped into the Lifeline and cited about 80 players for gambling.

The charges were later dropped, but more important, Gustin got what he came for: evidence of illegal gambling and payoffs to politicians. In the records were names of council members and deputy prosecutors; the wife of a former sheriff was also on the club’s payroll. And so much for bingo as a benign vice: Ledgers indicated the club was raking in up to $2 million a year. Seattle’s corrupt tolerance system suddenly went into spasms.

Chief Ramon declared there would be no further such raids. The three assistant chiefs fired back, saying Ramon was interfering with their lawful duties. Led by the rebellious Gustin, they issued a game-breaking ultimatum: Ramon had to step down, or they would ask for reassignment, which would be an embarrassment for City Hall.

As that impasse smoldered, an investigative report by KOMO-TV’s Don McGaffin revealed copies of checks proving that money from bingo clubs in the city and ‘burbs had gone to the campaign funds of 17 public officials, including city, county, and state legislators, along with King County Sheriff Jack Porter. McGaffin also detailed the Lifeline raid and Chief Ramon’s apparent attempts to downplay it. The chief had cut funding to his vice unit after the raids, slowing down enforcement efforts, and, it turned out, had released club operator Berger’s gun from an evidence locker as a favor to him. Ex-con Berger, McGaffin said, had a gun permit that had been issued by Sheriff Porter’s office, and the gun had once belonged to a deputy sheriff whose wife worked at Berger’s club.

The full story began to shape up, and the crusading McGaffin made the point to viewers that this wasn’t about some innocuous game of chance: “One of the sustaining myths of our time is that bingo is a game played by gray-haired little ladies in church basements for prizes such as electric blankets or toasters. This is the purest kind of nonsense. Practically every knowledgeable vice squad detective knows that bingo long ago turned into a huge commercial gambling operation.”

At interim mayor Miller’s urging, Ramon agreed to retire in October 1969, a month before the election of a new mayor who would be sure to replace the chief; Wes Uhlman, who won that election, had said as much in his campaign. The palace revolt by his assistants had succeeded in ousting Ramon after an often-praiseworthy 28-year career, tarnished in the end by scandal.

By the ’70s, Seattle was destined to host dueling grand juries—one federal, one state—looking into the surfacing story of Seattle vice. Colacurcio was indicted by a federal grand jury for racketeering, along with bingo- parlor operators Berger and Hoffman.

Hoffman was accused of making political payoffs, and Berger was accused of paying Colacurcio $3,000 a month per bingo location. In return, Colacurcio would “guarantee” that cops would maintain a tolerance policy and overlook gambling violations at the two men’s parlors. U.S. Attorney Stan Pitkin also claimed the three conspired to bring illegal gaming equipment across state lines—more than 100,000 bingo cards imported from Colorado.

“I have never had any payoff connections with police,” a bespectacled and balding Colacurcio, then 51, said of his first federal indictment. “On the contrary, the police have been trying to nail me to the wall . . . The next thing, they’ll say I took a lollipop from a kid.” Besides, Colacurcio added, the tolerance policy was approved by City Hall.

Charged in a bigger headline-making case was former assistant chief of police Milford E. “Buzz” Cook, who’d been a top assistant to Ramon. Cook, who also briefly became police chief only to be indicted for perjury, denied knowledge of the police payoff system that he helped facilitate. During his 1970 trial, officer after officer took the witness stand and testified about payoffs, giving some of the first public details on how the money moved through a system that dated back a quarter-century and involved at least 70 officers. Cash flowed from club owners who were pressured to make payments or did so in order to operate illegally and maintain their monopoly, with the booty going to cops and industry middlemen who pushed it up the line, doling out kickbacks of money, liquor, and other favors. Some cops were getting up to $1,000 a month.

Testimony was explicit, but much of it was unverified. One assistant chief, George Fuller, said he had “heard” that considerable cash had gone to city council member Charles M. Carroll (no relation to prosecutor Charles O. Carroll), known as “Streetcar Charlie” because of his former job with the old Seattle Transit System. Pinball machines were licensed under a committee overseen by Streetcar Charlie, and he was already receiving thousands in campaign cash from the amusement industry.

Fuller said Streetcar, as a council member, was reputedly getting $3,000 a month from a vice officer whose squad was sharing as much as $6,000 a month in payoffs. Vice cops kept payment records on index cards, with payees assigned code names. Those who didn’t pay on the first of the month would be faced with drop-ins by beat cops who harassed customers, checking IDs and turning up outstanding tickets or warrants. The officers kept half of what they were paid. The other half went to their sergeants, who kept half of that, and passed the remainder upward. Those at the top were getting money though different branches of the pipeline, leading to big monthly payoffs.

Among those testifying was Jake Heimbigner, owner of the Caper Club, a gay nightclub in the Morrison Hotel across from police headquarters, then on Third Avenue and James Street. He paid $165 in weekly protection money to stay open, he said. A police sergeant would call him and arrange meetings at various neighborhood locations, where the payoffs would be made.

Beverly Grove, manager of Russell’s Casbah Tavern and Cardroom on East Madison Street atop Capitol Hill, said she paid $125 a month to the cops, then one day decided she’d had enough. Suddenly there was a lot of police work to do at the Casbah. Cops began ticketing customers for traffic violations and jaywalking, she said. Her father, the tavern’s owner, said a cop told him that bar work can be dangerous, and “I’m sure you don’t want anything to happen to your little girl.” Unable to make money, the Casbah closed.

Cook was convicted and went to prison in a tumultuous time for the SPD. Besides the corruption, the department was dealing with antiwar protests and bombings around Seattle, and rioting was an almost-daily event in the early ’70s. New mayor Uhlman told a U.S. Senate committee there had been 90 explosive and incendiary devices set off from February 1969 to July 1970, damaging businesses, schools, churches, and private homes. Seattle ranked behind only New York and Chicago in the number of protest bombings; per capita, Seattle ranked first. Police officers regularly worked 12-hour shifts and patrolled the streets six to a car, dressed in full riot gear.

It was a war about war, with cops responding to demonstrators with beatings. In one University of Washington event, cops even covered up their names and badge numbers so they couldn’t be identified in the assaults. More than 300 brutality and misconduct complaints were filed in 1969 alone. Cops went from being called bulls to pigs. SPD officers in return adopted a pig as a mascot and coined the motto “Pride, Integrity, Guts”: PIGs.

Mayor Uhlman had just appointed an assistant chief, the respected Frank Moore, as top cop, when Moore too became tainted by scandal, invoking his Fifth Amendment right before a federal grand jury. Moore then stepped down “due to his health.” Uhlman began to bring in a series of outsiders, all California cops, to serve as interim chiefs. (Seattle would run through six police chiefs from 1969 to 1970.)

The department discovered that as many as 40 officers were involved in the payoffs, which appeared to have, for the most part, ended in 1968. Most of those named had already left the force. SPD officials asked prosecutor Charles O. Carroll to press felony charges against four officers who shook down businesses that catered to gays and lesbians, but he opted for misdemeanor charges and sought only suspended sentences.

Seattle attorney Christopher Bayley saw that as something of a cover-up, and signed up to oppose Carroll for the prosecutor’s job in 1970. A county grand jury could get at some of the illegal low-hanging fruit of the payoffs that a federal grand jury couldn’t, he said. Bayley easily won the election, kicking out the embattled Carroll after a 22-year reign.

As one of his first duties, Bayley formed a grand jury that in 1971 indicted both Charles Carrolls, along with 17 others—including ex-chief Ramon, his former assistant Cook, and former county sheriff Jack Porter—for “conspiracy against government entities.” Eventually, a hundred cops, many retired, were implicated in crimes dating back 35 years.

Prosecutor Carroll’s conspiracy role, the grand jury alleged, included being present at a meeting with pinball czar Cichy and Sheriff Porter to figure out how to extend a tolerance policy countywide. It was a low point for Carroll, an All-American running back at the University of Washington in 1927–28 and a 1964 National Football Foundation College Hall of Fame inductee. (Most legendary was his 1928 performance in a game against Stanford. Even though the Huskies lost 12–0, Carroll dazzled the crowd with such slash and dash that the Stanford players carried him off the field. President-elect and Stanford alumnus Herbert Hoover was so wowed, he exclaimed, “That man is the captain of my All-America team!”)

Bayley later said he considered fellow Republican Carroll the closest thing to a local political boss. Carroll had dirt on almost everyone and used it to bend arms, Bayley said. Carroll had also been the first prosecutor to introduce the televised confession. Now and then he would show up on TV, sitting at a table with the suspect sandwiched between him and a deputy prosecutor. The perspiring suspect would explain how he did the awful crime, as Carroll nodded affirmatively for the cameras. Not only did Carroll score campaign points, but the dog-and-pony show was much cheaper than an actual trial.

Once he dethroned Carroll and handed down the indictments, Bayley was on a downhill course. He was forced to drop some cases, including Streetcar’s, while others were dismissed. By the time of trial in 1973, plea agreements and pretrial rulings trimmed the defendant list to 10. Ex-chief Ramon, who was alleged to have received liquor from operators of gambling establishments, got the charges against him dismissed before trial, after it was determined he’d testified before a grand jury under a grant of immunity. Then King County Judge James Mifflin dismissed most of the remaining cases, including Carroll’s. The evidence against the former prosecutor was particularly troublesome, the judge said, as Carroll’s accuser had admitted to some earlier legal run-ins and court appearances wherein he’d often lied under oath.

In April 1974, the final defendant, a former cop, pleaded guilty to accepting bribes and was sentenced to two months in jail. Chuck Carroll would later claim he never approved of the tolerance policy. “I said bring me the facts for a case and I’ll file it,” he said. “I always worried that there might be payoffs to permit the stakes to go higher and higher. And that’s what happened. The names of some good people were dragged through the mud”—including, he inferred, his. When Carroll died in 2003, prosecutor Norm Maleng, the man who succeeded Bayley, said, “He was really a giant of his era, both in the sports and legal arenas. He was a grand old man, and I miss him. I really do.”

The city’s biggest corruption scandal ended with a whimper. But in a January 2007 op-ed piece he wrote for The Seattle Times on the 40th anniversary of the Wilson twins’ series on the shakedown system, Bayley said the indictments were, at least, a learning experience for the city. “Seattle finally began to understand how its legal and political system had been corrupted by years of payoffs . . . We forget those events at our peril.”

One who never forgot was Gordy Brock, one of the bar owners in that era victimized by police payoffs. He ran the Fremont Tavern (later the Red Door) and a number of other places, including a rough bar on Capitol Hill where the lights occasionally failed. “When they came back on, everyone would be pointing a gun at everyone else,” Brock said. But it was the cops who really worried him during his half-century in the business, in which he wound up as owner, with wife Sandee, of the Pike Place Bar & Grill at the market. He was among the last of the old-time tavern keepers and payoff victims still in the industry.

“The beat cops were bagmen, and I mean that literally,” he said. “Every week, I put a paper bag on the bar. The beat guy comes in, sits down, has coffee, picks up the bag [with $100 cash] and says goodbye. In return, I don’t get busted for code or liquor violations.”

His bagman was never indicted, Brock said. In fact, he got full city retirement and hung around Brock’s bar for years afterward, mooching drinks. It was some solace that post-tolerance mayor Uhlman showed up to cut the ribbon at Brock’s renovated Pike Place Market grill years later.

“Still,” Brock said of the mayor, “I wanted to ask him for my money back.”