On December 7 the Low Income Housing Institute held a grand opening celebration for a new housing development in the Central District, called Abbey Lincoln Court. The development, containing 68 apartments of various sizes, is situated in a neighborhood with a history of ethnic diversity and African American culture. Historically, before gentrification transformed it and so many other city neighborhoods, the Central District was a relatively affordable place to live.

Mayor Ed Murray, speaking at the celebration, framed the new development as a step toward bringing affordability back to the character of the neighborhood.

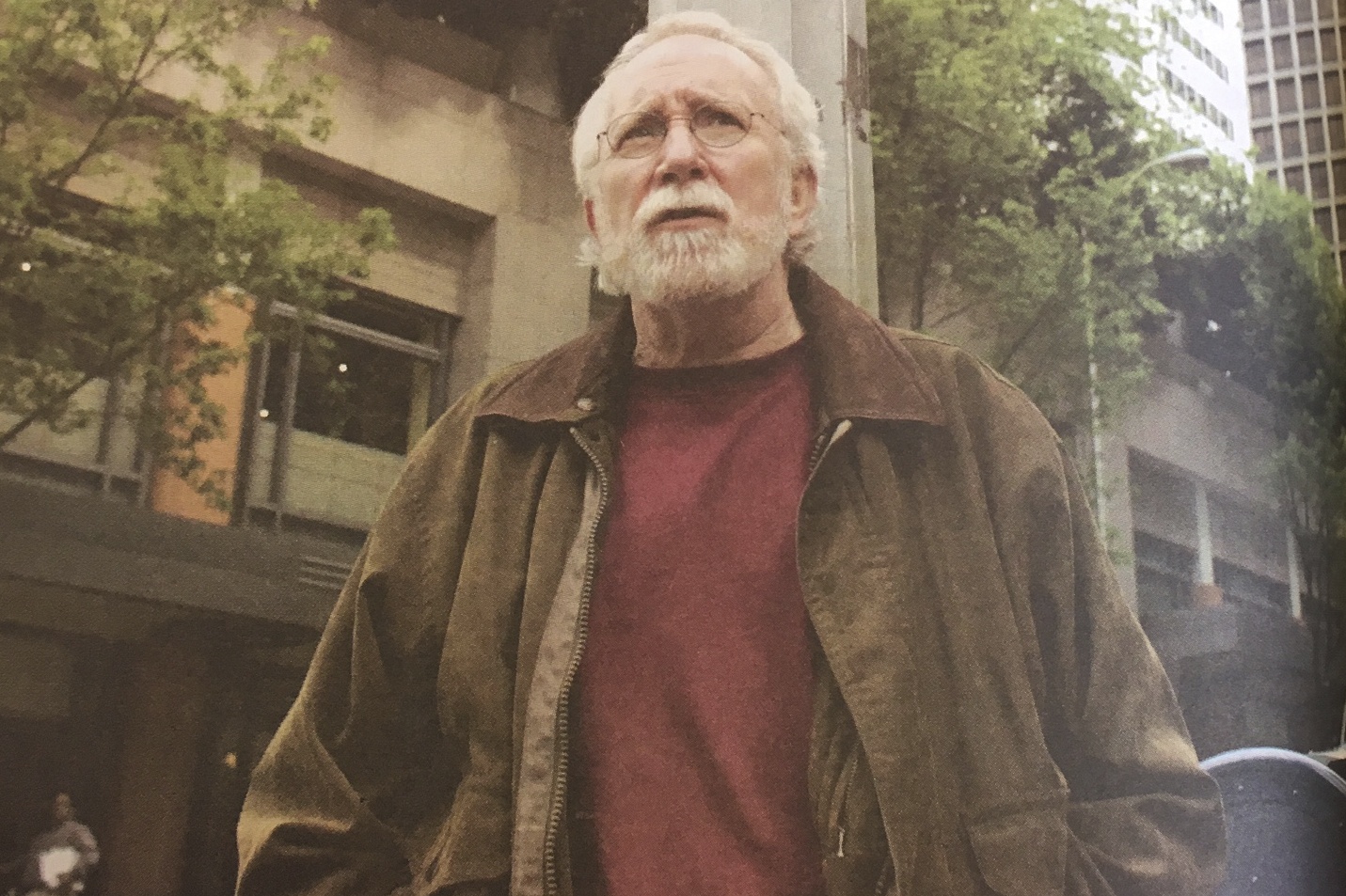

For Cathy Homan, a new resident of Abbey Lincoln Court who told her story at the opening ceremony, the opportunity to live in the low-income complex was a godsend.

“Without affordable housing I would still be homeless—it’s as simple as that,” she says.

Seattle recently became one of the nation’s most in-demand housing markets. Unsurprisingly, our city also is undergoing a severe crisis in affordable housing. In an effort to address the city’s housing affordability crisis, Murray’s Housing Affordability and Livability (HALA) action plan is gradually growing the limited pool of housing units set aside for low-income people—places like Abbey Court.

However, few believe the supply of affordable housing in Seattle will ever meet the demand, which means snagging one of the newly minted units is an ordeal in itself.

“Once the housing exists, generally there is such great demand for it that we don’t have to advertise it too much,” says Aaron Long of LIHI. “The demand for low-income housing far outstrips the supply.”

Homan’s path toward finding her home in Abbey Lincoln Court was not simple. Made homeless in 2009 after she decided not to continue living with a drug-dealing roommate, Homan lived in a shelter in Monroe, Washington; spent almost a year-and-a-half in the Aloha Inn Transitional Housing program in Seattle; then moved to Olympia on a Section 8 voucher and stayed there in a substandard apartment for four years. In Olympia, Homan’s daughter was bullied so severely in school that she felt it was no longer safe to live there. Homan started checking all the housing agencies in Seattle for openings.

“Every place had a waitlist, or my voucher wasn’t high enough,” she says. “I figured I’d never get to move.”

After learning about the soon-to-open Abbey Lincoln complex from LIHI, Homan sent in her application—one of about 300 applications for just 68 available units. While different agencies have different procedures for dealing with such high demand—including first-come, first-served—in Seattle the common practice is to enter all eligible applicants into a lottery. With the help of a computer, they chose who will get housing and who will be left to keep searching. According to Kerry Coughlin, SHA spokesperson, lotteries are standard practice throughout the low-income housing world in Seattle and King County.

As luck would have it, Homan won the lottery, and moved in. After living in Olympia for four years, yet never feeling at home enough to finish unpacking, she was finally home. “This is my forever home,” she said at the opening ceremony.

Though she eventually found her home, she describes the two-and-a-half year process as a “headache.”

Murray’s administration aims to increase the number of new housing units in the city to 50,000 within 10 years, with 20,000 of these units set aside for affordable housing.

Thanks to HALA, Seattle is seeing a growth in affordable housing for low-income people, who are defined as making 80 percent or less of Seattle’s Area Median Income (AMI). Seattle’s AMI was around $80,000 in 2015, up from $65,000 just four years ago—adjusted according to household size. (So, if you’re a household of one and you make $50,000 per year, you’re considered low-income; the same is true of a household of 8 making $95,000 a year).

The hope is that low-income units can allow people of mixed incomes to live throughout the city, including in expensive or desirable neighborhoods like Capitol Hill.

Despite the already-great demand, housing nonprofits do outreach, and work together with each other, the city, and other nonprofits to make sure the words gets out to the right people.

If someone in Seattle were to just Google “affordable housing,” they’d easily find a link to the Seattle Housing Authority (SHA), which provides about half the city’s subsidized housing and also administers vouchers for low-income people to find affordable market-rate housing, according to Seattle Housing Authority spokesperson Kerry Coughlin. The SHA does some advertising, sending out press releases and placing ads in community and ethnic newspapers, Coughlin says. “We do quite a bit of proactive outreach.”

This outreach is mostly for the voucher system whereby low-income people can get help paying for market-rate housing, according to Coughlin. The SHA doesn’t spend much time or money advertising its subsidized housing. Demand is too high, and the waitlists too long for that to make sense.

The SHA also partners with other local nonprofits to reach the people who need housing. If someone came into a health clinic, or a refugee women’s organization and said they needed housing, they would likely be referred to the SHA, Coughlin says.

The Seattle Office of Housing (which is a city agency and, unlike the similarly-named Seattle Housing Authority, does not manage housing itself), also provides resources for those looking for affordable housing. Its website links to housingsearchnw.org, which allows people to search for housing based on their desires and constraints. For example, says communications director Todd Burley, someone who wanted to live in Ballard and could afford $900 per month can input these parameters into the search. The Seattle Office of Housing also provides information about the dozens of housing nonprofits in the city, which Burley notes each have different strengths. Some organizations might be better for someone just coming out of homelessness, for example. Some agencies focus on different income brackets.

According to Burley, many people find affordable housing after calling the King County crisis line 211, whose operators know where to direct people. Shobe of Bellwether says most people find the agency through general ads the agency places, especially those in Craigslist and housingsearchnw.org.

Looking for affordable housing does seem to be a lot easier for those with internet access.

“Ninety-nine percent of the information is available online,” says Homan of Abbey Lincoln Court, reflecting on her own search for affordable housing. “I don’t know how to bust that barrier, and I don’t know if they need to actually go and stomp the streets and actually physically hand out the information.”

Still, housing agencies find other ways to reach people. Ashwin Warrior, spokesperson for Capitol Hill Housing, says the housing agency has an office people can visit, and a phone line. Also, case managers refer people to the agency directly. The organization always looks for ways to improve its outreach, he says. “Affordable housing is one of those things where we’re never short of takers.”

news@seattleweekly.com

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the number for the King County crisis line. The number is 211.