“I feel like we’re starting to get to the finish line here,” Seattle City Councilmember Lisa Herbold told representatives of labor and business at this morning’s meeting of her CRUEDA committee.

(CRUEDA stands for Civil Rights, Utilities, Economic Development, and Arts, which are for some reason all lumped together into one committee.)

“Finish line” might be an overstatement. “Midway point” might be more accurate. Council has been working on whether and how to regulate schedules for workers, particularly in food service and large retail businesses, since March. But so far that work has been limited to CRUEDA meetings and preliminary talks within the pair of stakeholder groups (one for workers, one for businesses) that the city has convened over the past few months. Herbold’s office says they don’t expect a draft of secure scheduling legislation to be ready until the end of next month, and that draft won’t work its way into formal council consideration until early August.

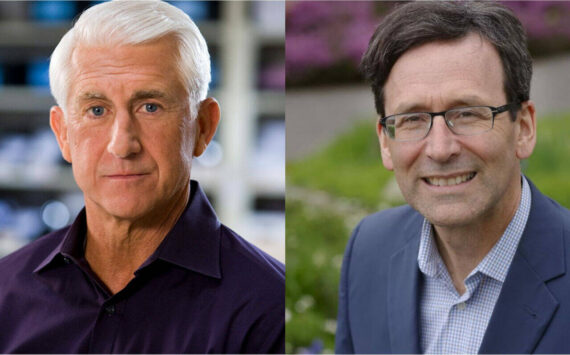

In the interim, Herbold and CRUEDA are waiting to hear back on two surveys they commissioned through Jacob Vigdor, a consultant who also teaches at the University of Washington. Vigdor will report on two surveys administered to employees and employers to help determine the groups’ respective priorities and concerns for the legislation. As with much workplace regulation, the secure legislation will have to balance the protection of workers with the independence of businesses. For instance, today’s discussion largely revolved around how to allow truly voluntary shift swaps between employees while still requiring businesses to inform workers of their schedules well in advance. Herbold called this balance “a tricky line to walk” in committee today.

According to her staff, the decision to build legislation from the ground up, based on Seattle stakeholders’ input rather than just cribbing from other cities’ (or interest groups’) legislation, was a conscious choice. The aim was to put all the negotiating and fighting on the front end of the policy-crafting process. Some of that fighting was evident in today’s meeting when Working Washington director Sejal Parikh responded to a suggestion that retail and food service employers need extra scheduling flexibility to ensure that employees who dislike each other aren’t scheduled to work together.

“That is super offensive,” she said. “I don’t know why we think low-wage workers are not able to control themselves.” David Jones, CEO of the local burger chain Blazing Onion and business representative at today’s meeting, concurred.

Not everyone is on board, though. Yesterday, Working Washington released an email that former Starbucks executive Howard Behar wrote on April 7 to councilmember M. Lorena González, who’s also heavily involved in the secure scheduling legislation. The letter, which was procurred by Working Washington through a public records request, was in response to a Seattle Weekly article on the legislation. It’s, um, frank:

Lorena

The question is do you believe in truth or do you believe in fiction. 70 to 80 percent of all scheduling changes are occurring because of employee requests or emergency situations like people calling in sick etc. Do you even understand how most scheduling occurs.

He goes on to criticize secure scheduling rules for subjecting companies to too much bureaucracy. He calls such policies a solution in search of a problem, writing, “If you are going to be creating legislation for a small percentage of people who are supposedly being treated unfairly you are going to be very busy.”

In Behar’s view, González has been a flack for labor groups. “It’s obvious that your mind was made up before you started this process,” he wrote in his letter. “I now am questioning if you are trying to help people or just penalize businesses for being in business.”

The letter concludes:

I am disgusted with this city government. You are not progressive you are permissive….permissive in allowing lies to go unchallenged, permissive in allowing our downtown to become an unwelcoming place to live by allowing drug deals to continue going on in our neighborhoods, permissive in allowing developers free reign. I expect more and so do a lot of other people. Can you please let common sense prevail

Warm regards,

Howard Behar

We contacted Behar to see if he still stands by that letter. “I stand by everything,” he says, arguing that his many years in business give him a better understanding of the actual effects of secure scheduling policies. “I’ve worked in retail for 60 years,” says Behar. “I’ve lived this stuff. I understand it. … I led an organization with a quarter million people, I know what the issues are. … Do some people get some bad schedules once in awhile? Of course. It’s retail.”

Behar also attacks some of the empirical premises behind the legislation—for instance, how common it is for workers to have to work consecutive closing/opening shifts. “This whole clopening issue is a fake issue,” he says. “There’s no reason to do that. [Managers are] not mean.”

While the problem of insecure scheduling is fake, Behar says, the consequences of schedule regulation—any regulations, not just those currently under consideration by the Council—wouldn’t be. “If all the sudden somebody gets sick and you don’t have enough people … then what are you going to do?” he asks. “How do you give the employees the complete right to change their schedules but force the company not to?”

We weren’t able to reach González for comment. But she did say this in the April 5 article that Behar was responding to: “You can’t start at a place where you are wholesale denying what [workers] are experiencing.”