It was in the 1970s that Seattle reached a high-water mark for middle-class, consensus reform. That idea now seems rather quaint, as “consensus” is suspected of being exclusionary and tame. But such reform, embracing both the establishment and its challengers, provided the script for a generation of civic improvers in Seattle. It was the same in many other American cities, which were on the endangered list then, fearing blight, white flight, suburbanization, and economic decay. A crusade to build “good cities” was born, and Seattle earned a leading role.

The movement started with the 1962 World’s Fair, which raised local ambitions for sports, science, the arts, and global trade. Next, it was boosted by the formation of Metro and Forward Thrust, an all-together-now effort in the late 1960s to upgrade sewers, transit, arterials, parks, and community centers and to build the Kingdome. Social services were expanded and funded by Model Cities programs. Cities feared “long, hot summers” of racial unrest and economic hollowing-out. So they formed nonpartisan coalitions and elected pragmatic activists such as Gov. Dan Evans and Mayor Wes Uhlman to rouse sleepy, low-tax governments. Can-do was in the air.

These reformers set out to stop a few freeways and to build transit, stadiums, parks, greenways, historic districts, dense downtowns, integrated schools, a major research university, urban boundaries to contain sprawl, a modern port for the container trade, a modern airport, lots of arts organizations, and a tech-centric, trade-based economy.

The unifying vision was a city of shared prosperity, widespread opportunity for all classes, (very) affordable housing, good schools, and nearby hiking. The goal was to build a stable economy not anchored to the fortunes of a single company (in this case Boeing), reform the police department, and bring to power an environmentally smart, open, and honest government. The city, activists hoped, would be home to a thriving and civically engaged middle class, modest regionalism, a culture of courtesy and “niceness,” low congestion, racial harmony, and plenty of art and architecture and design.

Much of this vision ran out of steam before reaching the Promised Land. The Civic Seattle consensus gave way to narrower and more suspicious special interests. Once the federal money ran out for the War on Poverty, local governments were forced to find dollars to sustain those programs and agencies. So began the long shift of money from basic services (roads, police, parks, schools) to social-service organizations that had built up strong constituencies.

Most of all, the bigger vision of Global Seattle rewrote the more modest first draft of a Civic Seattle. Just as Boeing had changed everything after World War II, Microsoft (“born global” like its eventual neighbors Amazon and Costco) changed everything after the 1980s. The 1970s now seem like an atypical interlude in Seattle’s long emphasis on commerce.

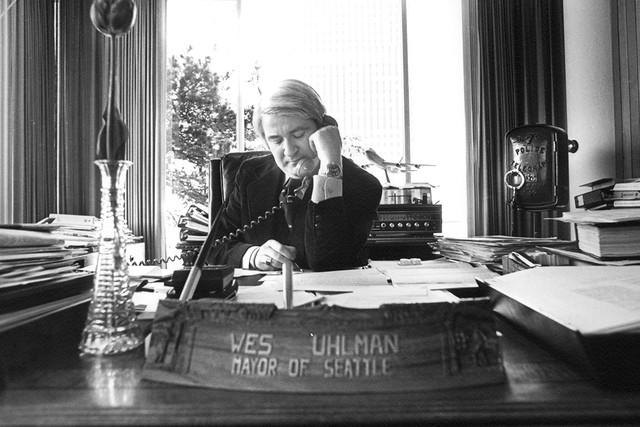

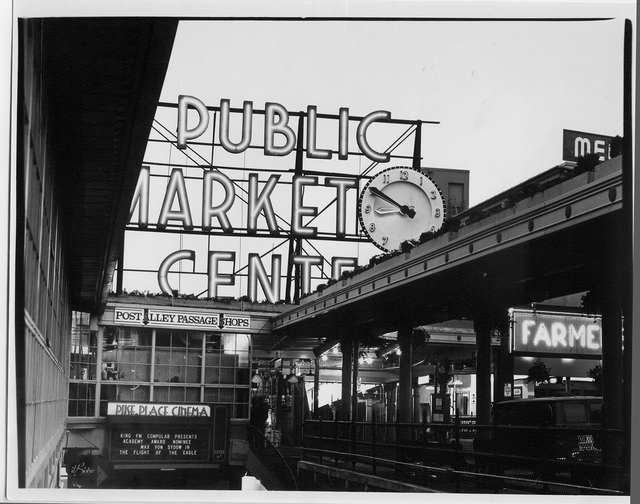

This civic spasm turned out to have some advantages that were not to be repeated. Sen. Warren Magnuson used his seniority to direct massive federal dollars to the city and the University of Washington, outflanking the hostile state legislature. Seattle gained a strong-mayor system when the Legislature shifted budget authority from the musty-crusty City Council to the mayor; and promptly an ambitious Democratic mayor, Wes Uhlman, was elected in 1969, tossing aside the business establishment. A new preservationist, anti-car, anti-establishment coalition was forged in the battle to save the Pike Place Market in 1971, and it has only grown stronger.

Organizations such as CHECC (Choose an Effective City Council) and Allied Arts spurred the rise of an establishment counter-elite, drawing from both parties (Republicans were progressives in those days) and young urban professionals, then called yuppies. They transformed the Seattle City Council between 1967 and 1973 and tossed out a corrupt, conservative Republican machine at the King County Courthouse in 1970. Reform snowballed. “Aim high” was the motto.

It was the start of a classic pattern of regime change, under which rising young political actors create a common agenda and then elect a leader to enact it. Gov. Dan Evans had done so at the state level from the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s, civic leader Jim Ellis did so in the metro region, and Mayor Uhlman did likewise in Seattle from 1969 to 1977. The result was to shove aside the small-business, narrow-agenda political culture of Seattle when it was a “big small town.” But, true to Seattle’s boom-and-bust economy, the Age of Reform soon was disrupted.

When Gov. Evans delayed too long his decision not to seek a fourth term, no successor was in place, and Democrats elected the mercurial conservative Dixy Lee Ray. That lurch shifted political dominance to the Legislature, where it remains today. State government never really recovered. The Republican Party, a branch of progressive “Rockefeller Republicans” under Evans, began its long march into the wilderness of fundamentalism and anti-governmental Reaganism. Seattle was politically marooned.

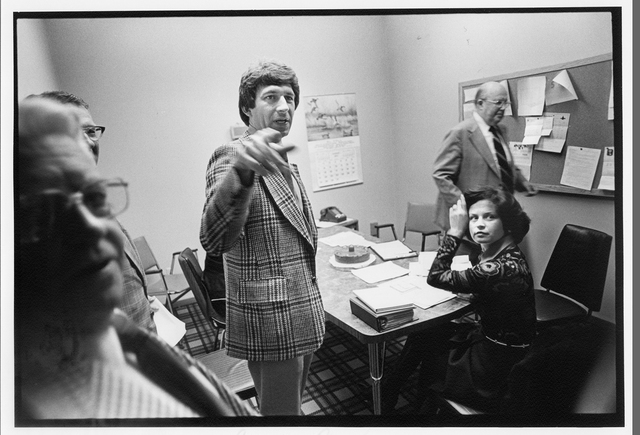

Another disruption of the reformist march came in 1977 when Charles Royer, a former journalist with no electoral experience, rallied many of the “outs” (neighborhood activists, anti-freeway folks, ethnic groups) to surprise the Reform Establishment candidates. Royer defeated Paul Schell, who had worked in the Uhlman administration and represented the core values of the reformers. Schell eventually did become mayor, in 1999, but by then the old civic alliance was too tattered to save him.

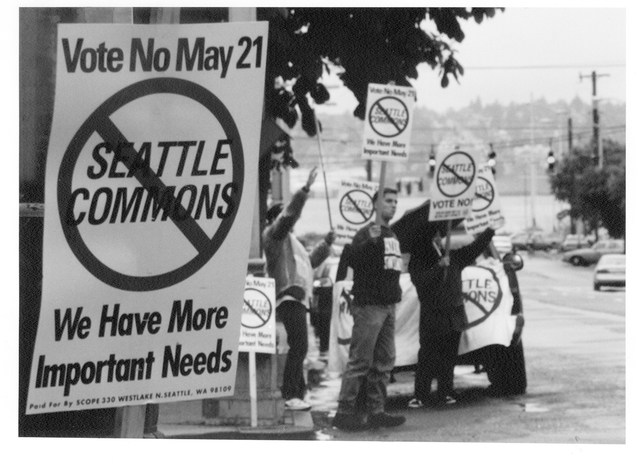

The bipartisan mood gave way to a long leftward veer and intensifying skirmishes between liberals and leftists. Big projects became much harder to pull off. School desegregation backfired, school reform fizzled, the Commons sank, the waterfront tunnel became highly divisive, metropolitan governance proved a vanishing dream, Westlake Mall turned out poorly, transit arrived too late.

The luxury of partisan feuds replaced the urgency of unified efforts. Back in the 1960s and ’70s, Boeing business cycles produced sharp economic downturns for half of each decade, so there was much more emphasis on economic growth. Similarly, more local banks and other Seattle-owned companies were political stakeholders. Seattle was “in-sourced.”

Density, today’s key value, was then defended in economic terms: It enabled downtown businessfolk—mostly lawyers, not techies—to rub elbows more efficiently. “Saving downtown” was a unifying economic slogan, rather than, as it is today, a fight over slices of the pie. Most agreed that single-family homes—costing about $50,000 back then—were one of Seattle’s great economic advantages in attracting talent, rather than being the highly divisive moral issue they are today. Affordability was taken for granted. Minority issues seemed limited to African-Americans and school segregation. Today’s issues focus more on amenities (pot and bikes and nightlife) and identity politics (gays and minorities). In the 1970s, economic competitiveness bumped self-actualization values off the governmental menu.

The result, though temporary, was that consensus on the civic playbook was easy to achieve in the 1970s. Consensus drew talent into government, for big things could be accomplished there. Similarly, the 1970s attracted many ambitious people to the city. Seattle was then a very “sticky” place for talent, and many stayed long enough to build major, excellent institutions—probably the decade’s most enduring legacy.

The list is impressive: Greg Falls of ACT, George Duff and Bill Stafford at the Chamber of Commerce, Speight Jenkins of Seattle Opera, Dick Ford at the Port, Aubrey Davis at Metro, Kent Stowell and Francia Russell of the Pacific Northwest Ballet, Bill Gerberding at UW, Bill Sullivan and Steve Sundborg at Seattle University, Gerard Schwarz at the Seattle Symphony, Bill Massey at the Municipal League, Peter Donnelly at ArtsFund, Rev. Sam McKinney as a power broker for black politics, families such as the Gates, the Blethens, the Nordstroms, the Chihulys and the Stroums, Ann Farrell at The Seattle Foundation, Congressman Norm Dicks, Jim Ellis and his long fight against sprawl, Ginny Anderson at Seattle Center, Virginia Gunby for environmentalism, Denis Hayes at the Bullitt Foundation, Bagley and Virginia and Charlie Wright for the arts, Tomio Moriguchi for the Asian community. Seattle Weekly is on that list as well.

Forty years after the birth of this publication, it’s an open question for me whether the fast start of the 1970s was a seed-time or a false spring. Seattle has always been a dynamic quick-change artist among cities. So it’s not surprising that the civic consensus of the 1970s lacked staying power. Regardless, that decade seeded the birth of a modern city that now plays an outsized role on the world’s stage. “Aim high” we certainly did.

David Brewster founded Seattle Weekly in 1976. He served as publisher and editor until selling the publication in 1997.