Physician Robie Sterling, who recently finished his residency at Seattle’s Swedish Medical Center, was the only volunteer doctor inside the medical tent at Oceti Sakowin camp on Sunday, November 20, when the call came in over the camp radio: Protesters needed help.

“Police had started to shoot projectiles” at the demonstrators, he says, including rubber bullets, “and teargassing them. It became really clear that it was a different situation than we’d seen in prior days.” Between about 5 p.m. and 3 a.m., when Sterling went to bed, he estimates that the number of people who came through the camp to seek medical attention was “definitely in the hundreds.”

Injuries ranged from the eye- and chest-burning effects of tear gas to temporary hearing loss from nearby explosions to dangerous head injuries from flying projectiles.

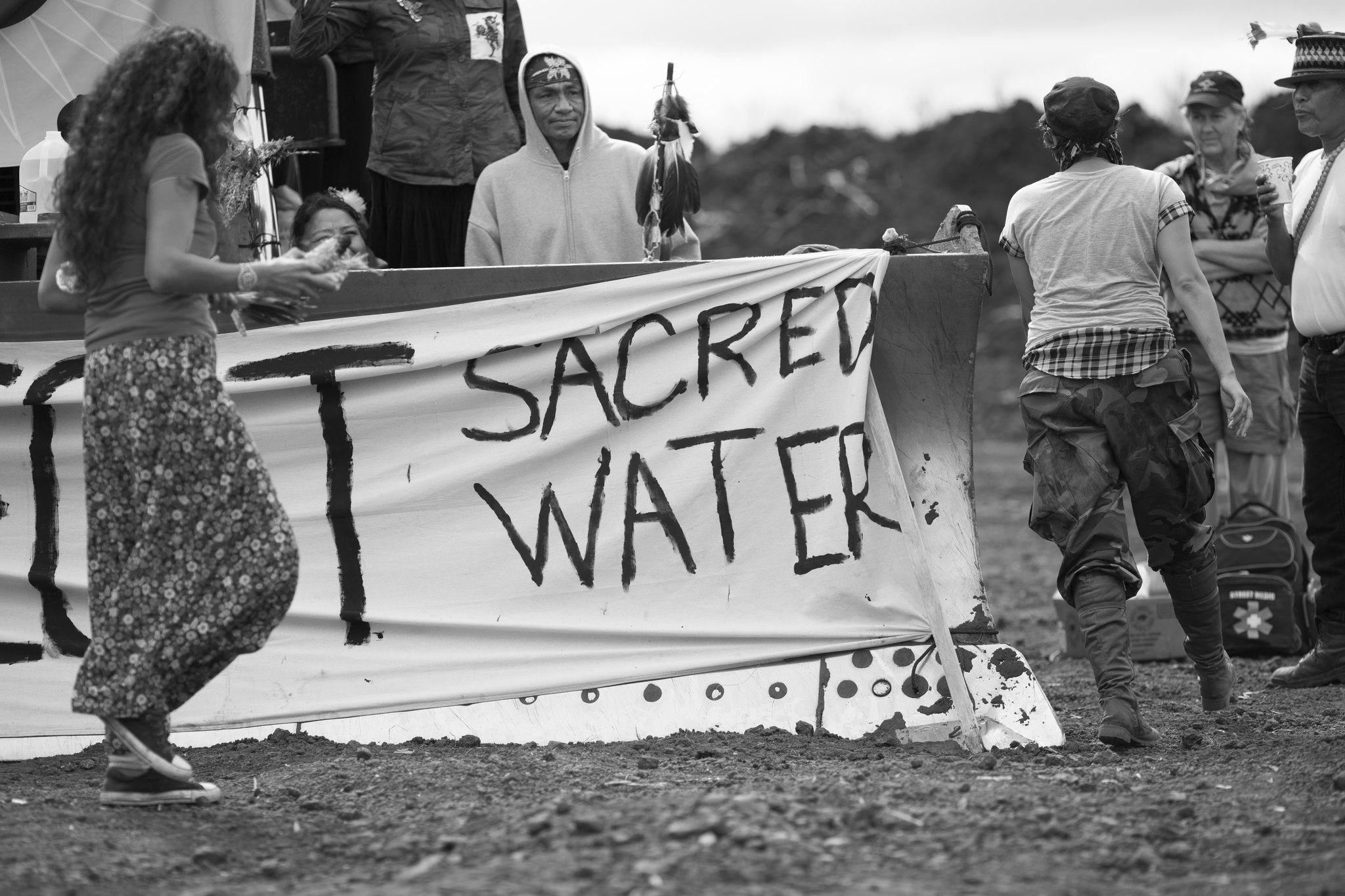

As the bitter North Dakota winter sets in, the situation is tense at Standing Rock, where thousands remain to defend tribal soverignty against the 1,172-mile Dakota Access pipeline. The oil pipeline would, if built as planned, abut the Standing Rock Sioux reservation and run underneath the Missouri River, upon which the Sioux (and millions of others) depend for clean drinking water.

Last Sunday, police tactics turned violent (again), and escalated to the point that some are now calling the event “Bloody Sunday.” As some protesters, also known as “water protectors,” attempted to remove police-constructed blockades across Highway 1806, the quickest route to Bismarck and to emergency medical services, reports from the ground describe police use of concussion grenades, rubber bullets, mace, tear gas, and giant water cannons in sub-freezing temperatures. Law enforcement officials have described protesters as “very aggressive” and have defended the use of these weapons for crowd control.

But some injuries are indeed severe. New York-based activist Sophia Wilansky may lose her arm; Sterling helped treat one woman who’d been shot directly in one eye. “It was a serious enough injury, I was afraid she’d lose her eye,” he says. Sterling and the other physicians alerted a local ambulance service on Sunday night that transported everyone in unstable condition to the main hospital in Bismarck, but he confirms that the police barricade on Highway 1806 may have significantly increased travel time to urgent medical care. Many were treated for hypothermia. Many showed signs of concussion. A United Nations human rights expert has called the use of force against protesters at Standing Rock “inhuman.”

“Walking through our outdoor triage area… it was twenty-something degrees, and people are crying, and people are screaming,” Sterling says. “You know, I don’t know what a war zone feels like. But it didn’t feel right. It didn’t feel right that this was happening to unarmed people who were just expressing their freedom of speech. This sort of violence being inflicted upon them. … It was very surreal.”

Sterling spent a week volunteering at Standing Rock. He says being able to do this kind of work is a big part of why he got involved in medicine in the first place, and he saw an opportunity to join two colleagues there who work for the Seattle Indian Health Board. Sunday was his last night, and the violence, to him, and to most of the people around him, was completely unexpected.

“I’m still processing it right now,” he says. “The amount of pain, and, I think, shock and anger about it, from the protesters and the medical staff… it’s something I’m still sort of dealing with.”

Questions remain as to how — and when — this struggle will end. Campers plan to stay the winter, and are building the structures they’ll need to weather blizzards and sub-zero temperatures. On November 14, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a statement saying the agency had “determined that additional discussion and analysis are warranted” after taking a second look at the contested area. As a result, the agency said construction on the disputed land will be put on hold. “The Army will work with the Tribe on a timeline that allows for robust discussion and analysis to be completed expeditiously,” the statement says. “We fully support the rights of all Americans to assemble and speak freely, and urge everyone involved in protest or pipeline activities to adhere to the principles of nonviolence.”

Seattle-area activists and tribes have been actively supporting the water protectors at Standing Rock for months, including through a paddle led by Pacific Northwest tribes in September and many local fundraisers. Sterling says there was definitely a strong contingent of supporters and medics from the Pacific Northwest the week he was there. And for anyone considering coming to the camp, he says, be forewarned that a North Dakota winter is serious: “They need to be prepared to sustain themselves with an appropriate structure and clothing.” In terms of donations and support, “money and skilled labor to put up structures [for the winter] is really what they need right now.”