South Park homeowner Jennifer Scarlett, a courier who delivers shipping documents to the Port of Seattle, received a message of her own last year from the City of Seattle. The postcard adorned with cartoon school buses and houses invited her to an ice cream social at the West Seattle Junction to discuss housing. But when she flipped over the postcard, she read in fine print that there might be zoning changes in her neighborhood.

At that meeting about a year ago at the now defunct Shelby’s Bistro and Ice Creamery, Scarlett learned that South Park is one of 27 neighborhoods that could undergo upzoning changes as part of the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda. She told Seattle Weekly that it was there that she learned about a city policy called Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA), which is billed as a way to “ensure that growth brings affordability.” The policy requires developers to include affordable housing in new projects or pay a fee for nonprofit developers to build their own. But the city needs to pass new zoning that adds development capacity for the requirement to take effect. The changes would affect all areas currently zoned for apartments and commercial buildings, but it will also impact a small percentage of blocks currently zoned for single-family homes.

At the meeting last winter, large maps of the neighborhoods were on display. “These city planners were standing around and talking about ‘Oh, we should put an apartment building here, we should put an apartment building there.’ And I was taken aback because I was like, ‘There are people living there right now and they don’t know you’re doing this,’” Scarlett said. So she and her neighbors joined an advocacy group and spent the next several months informing the neighborhood of the changes.

On Monday, that group, the Duwamish Valley Neighborhood Preservation Coalition, joined 25 other community organizations in filing an appeal to the Seattle Hearing Examiner. The focus of the appeal is the MHA final environmental impact statement (EIS), a 1000-page-plus document published on November 9 that includes details about implementing MHA citywide and expanding development to areas with transportation that the city views as at low risk for displacement.

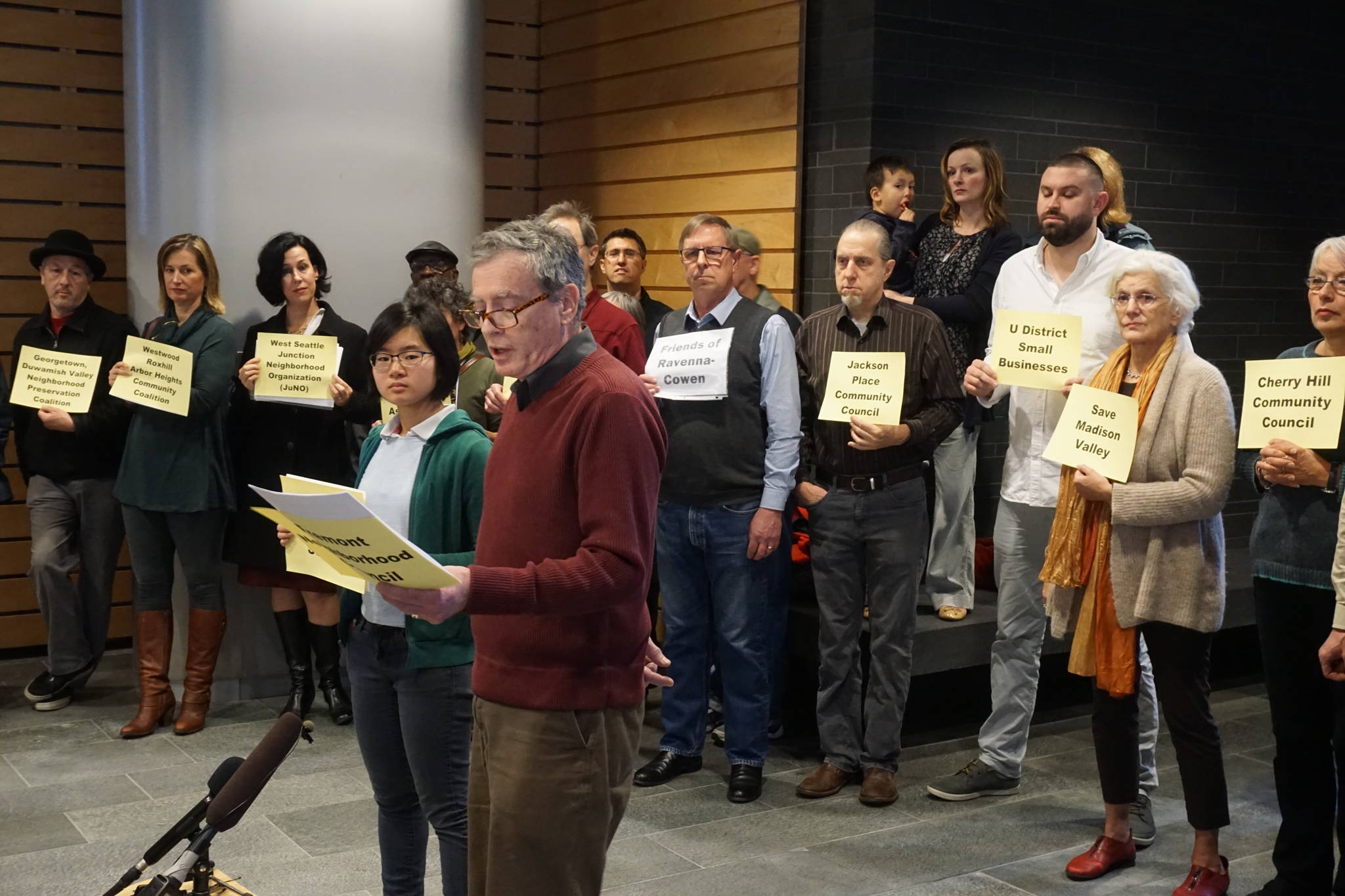

United under the banner of the Seattle Coalition for Affordability, Livability, and Equity, the groups held a press conference at City Hall on Monday afternoon in the foyer outside of the Bertha Knight Landes room, where members complained that the upzone changes would do the opposite of what they aim to do and would ultimately result in the displacement of low-income residents like Scarlett and communities of color. About 40 members held yellow signs bearing the name of their groups as they faced cameras and a few onlookers.

Those who spoke said that they fear the development will result in the destruction of existing affordable housing, the overpopulation of schools, and encroachment on the tree canopy. Instead of “one size fits all” upzones, they’d like the city to restore funding for neighborhood planning and advocate an employee head tax on large companies to generate revenue for affordable housing, said Seattle Fair Growth board member Sarajane Siegfriedt. “We’re not opposed to growth. Opposing growth would be like opposing gravity,” Siegfriedt, a member of the coalition, added over the phone on Monday.

Seattle Fair Growth spearheaded the formation of the coalition a couple months ago when an advisor to the group suggested it consider appealing the EIS. Seattle Fair Growth learned that the West Seattle Junction Neighborhood Organization was already meeting with an attorney about challenging the statement and decided to join forces.

According to the appeal filed late afternoon Monday, the coalition believes that the final EIS does not adequately describe how each neighborhood will be impacted by the proposal. The coalition complains that the statement fails to include canopy loss mitigration efforts that were offered during public comments. Nor does the EIS acknowledge the additional air pollution caused by development, they say. The appeal also alleged that the statement does not analyze the parking, traffic, and transportation impacts of the proposal. It disagreed with the city’s methodology for assessing neighborhoods that are considered to have a low or high risk of displacement. The city’s claim that the MHA would allow for more affordable housing in areas with low risk of displacement was inaccurate, they alleged, because developers would be more likely to pay the “low fee” and create market rate units in those areas instead. The group requested that the Hearing Examiner send the final EIS back to the city with the aim of creating another EIS that addresses the potential environmental impact and mitigation efforts for each neighborhood.

So far this year, the city has approved zoning changes for downtown, South Lake Union, Uptown, the Chinatown-International District, the University District, and parts of Central District. City officials estimate that, in all, the citywide upzones will result in 6,000 new affordable housing units for households making no more than 60 percent of the area median income over the next 10 years.

Scarlett is alarmed about the upzoning because she bought her home about 10 years ago and has a fixed income. “Now we’re worried that the increased taxes and the new luxury construction going on is going to drive up the taxes and that we’re actually going to be pushed out,” Scarlett said. Over the past year, speculators have increasingly asked her and her neighbors if they plan on selling their houses, she said.

But Jason Kelly, the Director of Communications for the city’s Office of Planning and Community Development, argues that increasing property values have long been a concern for Seattle residents. Zoning changes to allow for new development like apartments in areas previously zoned for single family homes could drive up property values, which would result in increased property taxes. The increased property taxes could create an additional burden on homeowners, but it is “not considered a significant impact,” Kelly said, because it would also increase equity that would benefit homeowners when they refinance or sell their homes.

Once Scarlett learned of the plans last year, she messaged a South Park neighborhood Facebook page and began knocking on her neighbors’ doors, only to learn that most people were unaware of the proposal. She and other members from the Duwamish Valley Neighborhood Preservation Coalition began distributing flyers and held a mini seminar on MHA. The coalition began holding meetings every Thursday at Napoli Pizzeria to discuss the zoning changes in their neighborhood. “I think they [the city] left it up to the communities themselves to figure out what was going on and to educate each other,” Scarlett said.

Kelly maintains that the city has gone door-to-door and held community meetings about the rezoning for two years. The City Council has already announced a slate of open houses and public hearings in 2018 and is preparing a mailing that will be distributed throughout the city.

The program was designed to direct more of the new housing capacity to areas that are at low risk for residential displacement, like in areas where rents are already high and residents have access to transportation. He added that neighborhoods with a higher percentage of immigrant populations and low-income families at risk of displacement would have fewer zoning changes. “The idea is to have the least amount of change required so that we’re not adding an additional incentive for developers to act in those neighborhoods,” Kelly said.

In response to Scarlett’s concern about the disappearing tree canopy, Kelly argues that a new zoning designation for blocks with single-family homes in South Park would actually benefit the tree canopy by requiring the retention of existing trees and the planting of new ones. “The idea is that when we do see change in these neighborhoods they also contribute to our goals of the tree canopy for the city.”

Some coalition members also worry that the zoning changes would remove current affordable housing options. Jon Lisbin, a small business owner and the president of Seattle Fair Growth, is concerned that the MHA would cause currently affordable housing to be bulldozed and replaced with multifamily units. He complains that the final EIS doesn’t offer any alternatives for accommodating growth. “They’re offering three flavors of the same thing. Do you want upzoning or more upzoning?” Lisbin said over the phone on Friday. He added in an email: “The deal itself pales in comparison to other major cities that are requiring 10 to 35 percent inclusionary housing on site or fees. In Seattle, downtown developer’s fees are as low as 2 percent.”

However, Kelly wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly that MHA is “an important tool for addressing displacement.” Because the proposal adds new capacity for more homes, the new EIS estimates that only one home will be destroyed for every 14 new homes; without zoning changes the ratio would be 1:10, he added.

During the Monday afternoon press conference, Jane Nichols from Save Madison Valley said that an urban forest in her neighborhood would be cleared to make way for development, to which a member of the public yelled: “Liar!” The onlooker accused the coalition, which consists of mostly middle-aged and white residents, of only representing their “rich neighborhoods” and that the members weren’t offering real solutions to gentrification. The press conference ended with coalition members erupting in protest at the accusation, insisting that many of them were renters representing their low-income neighbors.

The council is scheduled to hold public hearings and open houses in the beginning of 2018 and will vote on changes in August. Zoning changes would take place 30 days after the council vote.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com