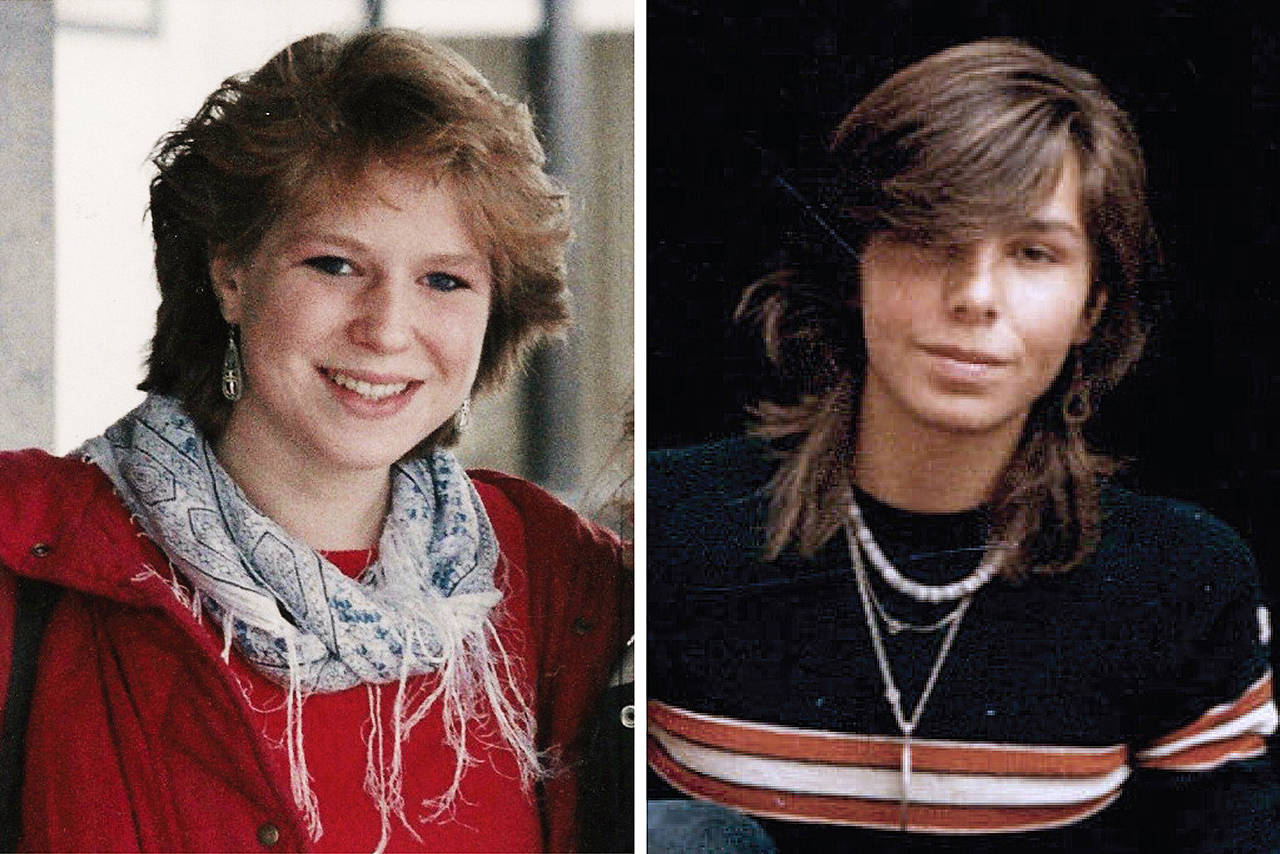

EVERETT — For three decades, the families of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg had only questions and fleeting memories.

On Friday morning, one long-awaited answer arrived.

A jury found William Talbott II guilty of two counts of aggravated murder in a trial that was the first of its kind.

The truck driver, 56, of SeaTac, had been identified in a pioneering investigation led by the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office.

A genealogist used a public DNA site, GEDMatch, to help build a family tree for the suspect based on DNA from a crime scene. Her research pointed to Talbott.

Since then, dozens of arrests have been made in cold-case crimes nationwide through a forensic method known as genetic genealogy, stirring a heated debate over police use of public ancestry databases.

Many suspects, including the former cop accused of being the Golden State Killer, await trial.

Talbott’s case marked the first time that the technique had gone before a jury.

Other than semen at two crime scenes, little else tied the defendant to the killings. His defense argued the semen was the result of a consensual act.

He grew up seven miles from a third crime scene south of Monroe, where Jay Cook had been bludgeoned with rocks, strangled with twine and left dead under a bridge in 1987.

Talbott did not testify.

He walked into the courtroom Friday dressed in dark gray. After a law clerk read the jury’s verdict — guilty as charged — he flinched and gasped.

“No,” he said, quietly. “I didn’t do it.”

Moments later his head lolled back and forth, as his attorneys put their hands on his neck and back.

Jail guards pushed him out of the room in a wheelchair.

Family and friends of the victims embraced.

Judge Linda Krese set sentencing for July 24. There is only one possible sentence: life in prison.

“While the main interest on this case has been focused on the use of genetic genealogy, we’ve been trying to find a killer,” said Capt. Rob Palmer, head of investigations for the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office, after the verdict. “It’s an amazing tool, and we’ll be using it again.”

Added Laura Baanstra, the sister of victim Jay Cook: “This would not have been solved if it had not been for the DNA evidence. The use of GEDMatch — I hope more and more people will be willing to allow their DNA on these sites so that this world can be safer.”

“Our family is very grateful for all the people that helped bring this to fruition,” said John Van Cuylenborg, brother of Tanya Van Cuylenborg. He thanked the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office and its cold case team, as well as those involved in the genetic genealogy analysis that led to Talbott’s arrest.

Jay and Tanya

Cook stood a stalky 6-foot-4.

At age 20, he hadn’t beefed out.

He’d learned to play rock ’n’ roll bass guitar with friends in his hometown on Vancouver Island.

He worked at a pizza parlor for a while. One night after a shift, he rode his bike three hours through rain and darkness to a cabin where friends were staying for a weekend, balancing a pizza the whole way to bring them food, recalled his sister.

The family of 1987 murder victim Jay Cook talked about their feelings after the trial of William Talbott II during an interview Tuesday, June 25, 2019, at The Daily Herald in Everett. (Chuck Taylor / The Herald)

He had a bizarre habit of losing his clothes, she said. Sometimes after school he’d come home without his jacket, with no idea where it ended up. One day the family packed for a ski trip, about a four-hour drive.

“We get there — snow on the ground, right? — and Jay only had one shoe,” Baanstra said.

He had a sweetness about him, taking his younger sister out for dinner and, once, for high tea with the good money he’d earned on a fishing boat.

One uncle coined a phrase about his nephew: “Jay had no rough edges.”

“It’s really no wonder that Jay ended up with someone like Tanya,” Baanstra said. “Tanya was very sweet and caring, and they looked up to each other.”

She was 18.

Much like the Cooks, her family loved long boating trips around the Salish Sea. Van Cuylenborg played tennis at her family’s home on an acre, and led a student push for a girls’ basketball team at her high school, her brother said.

For years she lobbied her parents, too, to get a dog. Her mother gave in around 1982. The Golden Retriever, Tessa, became first and foremost Tanya’s pet.

She hoped to work with animals one day, maybe as a veterinarian. Cook’s dream was to be a marine biologist. Neither had concrete plans. They were young. They started dating in the summer of 1987.

Cook’s father ran a furnace business with a man named Spud, whose last name, Talbot, ended in one T. Jay Cook didn’t have a job at the time. So his father asked him to run an overnight errand to pick up about $750 in parts from a company called Gensco, in south Seattle. He had cash for a hotel but planned to sleep in the van outside the business.

His girlfriend was invited to come along. They set out on Nov. 18, 1987, in a bronze Ford Club Wagon van. Their ferry from Vancouver Island docked in Port Angeles around 4 p.m., a half-hour before sunset. Perhaps an hour later on Highway 101, they missed the exit to the Hood Canal Bridge. They stopped in Hoodsport for snacks.

Store clerk Judith Stone testified that they wanted to know how close they were to the bridge.

“Oh, you’re a little past that,” Stone recalled saying. “A long way past that.”

She told them how to reroute to Seattle.

A deli clerk spoke with them in Allyn. They did not seem distressed, and it didn’t seem like anyone else was traveling with them.

Exactly how they encountered the killer remained a mystery, even through the trial.

Prosecutors suggested they may have pulled over for directions again.

Days later police found a ticket for the Bremerton-Seattle ferry inside the abandoned Ford van. The ferry docked in Seattle around 11:35 p.m.

That’s where the couple’s path went cold.

The case

Almost a week later, a passerby collecting cans found Van Cuylenborg dead against a rusty culvert, on Nov. 24, 1987, off Parson Creek Road in Skagit County.

She was nude from the waist down. She’d been shot in the back of the head with a .380-caliber bullet.

The next day, police learned her wallet, ID, a box of .380-caliber ammo and surgical gloves had been picked up 20 miles north in downtown Bellingham under a tavern’s back porch. The bronze van sat parked around the corner, next to a Greyhound station.

The money order was still inside, unused. There was blood on a comforter, a used tampon on the floor and orange Camel cigarette butts in an ash tray.

Pheasant hunters stumbled on Cook’s body on Thanksgiving Day under the High Bridge over the Snoqualmie River, south of Monroe.

A blue blanket covered his head and torso. Investigators peeled it back to find he’d had been beaten around the head and strangled with twine tied to two red dog collars. Tissues and a pack of Camel Lights had been shoved down his throat. Days later police seized bloody rocks from the grass nearby.

The crime scenes were scattered over three counties. At each site, police found interlocked zip ties. Neither of the victims had obvious marks on their wrists or ankles.

A generation passed.

For Cook’s parents and sisters, the gaping wound began to heal. They talked often about Jay, but in happy, friendly, joking terms.

“For us, I think we put Jay’s tragic death behind us a long time ago,” Laura Baanstra said in an interview. “We all assumed that whoever did it was either dead or in jail. I don’t think I ever thought the guy had gotten away with it, because I just assumed he would’ve done something else.”

John Van Cuylenborg, Tanya’s brother, said his parents were never the same after her death. When his father died in the 1990s, John became the one who kept in touch with the sheriff’s office in Snohomish County.

“What I’ve had to live with for 31 years was just no answers to anything, in this case, other than you had a couple of dead bodies,” he said.

John, his sister’s only sibling, is now a civil attorney in Victoria. He was forced to accept that there was a good chance the murders would never be solved.

“You kind of had to,” he said. “You needed to have some perspective on it, and be able to focus on other things in life, rather than continuing to wait day after day, week after week, for a resolution.”

He never gave up hope, though. He knew there was evidence that could, someday, implicate somebody. His sister’s Minolta camera body had gone missing from the van, and detectives had the serial number.

A jacket and a backpack had gone missing, too.

He knew the sheriff’s office had a suspect’s DNA.

He couldn’t have predicted how police ended up using it.

Detectives had built a list of hundreds of potential suspects. Many were ruled out through DNA tests.

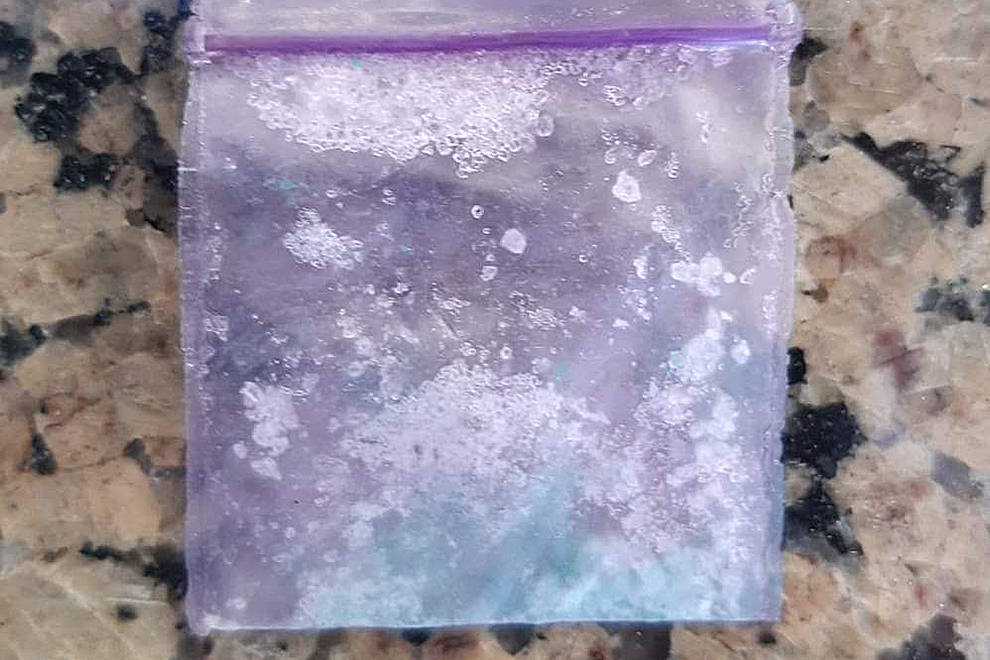

Semen was found both on Van Cuylenborg’s body and in the van, on the hem of her pants. The sample was sent to Parabon NanoLabs, a private lab offering a new service to help police to build a rough digital sketch of a suspect’s face, through DNA.

Behind the scenes Parabon was working on another project, using public genealogy databases to identify suspects through their family ties. Quietly, the lab uploaded the genetic profile to GEDMatch.

By chance, second cousins on both sides of Talbott’s family had uploaded genetic profiles to the database.

A genealogist, CeCe Moore, traced the family lines to Talbott’s mother and father. He had sisters. But he was the only son. The data report returned to the lab on a Friday in late April 2018. By that Monday, the genealogist had identified who it belonged to.

Until then, police had no reason to suspect Talbott.

He was a short-haul trucker with no felony record. In his spare time, he rode motorcycles, and he was well liked in his circle of friends.

Plainclothes officers put Talbott under surveillance on his driving routes for days. A paper cup fell from his work truck on May 8, in south Seattle. It was tested by a state crime lab. His DNA matched the semen. Talbott was arrested and charged with two counts of aggravated first-degree murder.

John Van Cuylenborg had been in touch with Snohomish County cold case detective Jim Scharf over the preceding months about the work Parabon was doing. Scharf called him in May 2018 with news of the arrest. Van Cuylenborg had many questions.

“And I said, ‘Well, where is he?’ And he said, ‘In the back seat.’ A shiver went down my spine, thinking Jim’s riding in the same vehicle as this guy, after 31 years, you know?” he said. “It’s just phenomenal.”

Later, detectives took a swab from Talbott’s cheek.

Again, the DNA matched.

The trial

Defense attorneys did not challenge the legality of police using genetic databases to identify a suspect.

Instead, at least in this trial, the genealogy work was treated like any tip that police might follow.

Jurors listened to 1½ weeks of witness testimony: retired police officers who uncovered evidence in 1987; the bird hunter who found Cook’s body; the Bellingham bartender who gave Van Cuylenborg’s ID to the cops; the store clerks, the last people known to have seen the couple alive; and detective Scharf, who fought tears on the witness stand as he recalled receiving word of a DNA match.

According to Talbott’s defense, the detectives had tunnel vision.

“They never stopped to consider that perhaps the person who left the DNA was not the murderer,” defense attorney Rachel Forde said during the trial.

In her closing argument, Forde said semen could’ve been the result of a consensual act. It only showed, she said, that Talbott had sexual contact with her. It didn’t prove Talbott was guilty of murder, Forde said.

The deputy prosecutor, Matt Baldock, fired back in his rebuttal.

He asked the jury if it was plausible that a teen girl would have sex with a stranger — on an overnight trip with her boyfriend? In the midst of the AIDS crisis? When she was on her period?

Attorneys clashed over the credibility of a witness who found further evidence that seemed to link Talbott to the van: a palm print, on a back door.

At first, a Washington State Patrol crime lab investigator had ruled out Talbott as a match.

A colleague told forensic scientist Angela Hilliard to look again. Hilliard realized she’d been examining the sample upside down. She changed her conclusion: The print matched Talbott.

The defense pointed out how convenient that seemed for the police but did not call an expert witness to challenge the final conclusion of the lab, nor did the lawyers dispute it was Talbott’s semen in the van.

Defense witness testimony lasted about 10 minutes — a brief discussion of an address on Talbott’s driver’s license in Okanogan County, where he owned land.

Talbott grew up near Woodinville, in a house that’s no longer there. At the time of his arrest, he lived in SeaTac.

None of his relatives recalled ever seeing him with a blue blanket, a Minolta camera, dog collars or guns.

The jury began deliberating around 4 p.m. Tuesday.

The answer

As they awaited a verdict, Cook’s family spoke with The Daily Herald.

“Regardless of how this case comes out, I know they’ll survive,” said Cook’s brother-in-law, Gary Baanstra. “I’ve seen them do it. Their closure is just going back to that place where they can say, ‘Jay,’ and there’s just no baggage against it anymore.”

To Cook’s sister, it has seemed mind-boggling that a killer could do this once. Never before. Never again.

Tanya’s brother has thought about that, too.

“We’re trying to logically understand an illogical act,” John Van Cuylenborg said. “Or acts, in this case. You’re starting off to do the impossible.”

Sitting outside the courthouse on a sunny evening this week, he said he believed Talbott was guilty.

He’d seen what the jury had seen. He could come up with no other explanation for the evidence.

Jurors returned a verdict around 11 a.m. Friday. Defense attorneys did not stay to talk with the 12 Snohomish County residents who had convicted Talbott.

After over an hour of discussion with prosecutors in a closed room, most of the group trickled out of a back exit of the courtroom. At least one juror was wiping away tears. None were willing to talk with media right away.

A national spotlight has followed the trial this month, because it is uncharted legal and ethical territory.

Snohomish County Prosecutor Adam Cornell spoke to a wall of television news cameras outside the courtroom.

“Justice arrived late for Jay and Tanya, but it arrived today,” he began.

Genealogy research had been critical in cracking the case, he said, but it was dogged detective work at the sheriff’s office — running down leads, using every strategy at their disposal — that brought justice for the families.

“Folks aren’t going to be able to get away with murder anymore, when we have this information,” Cornell said. “And if you’re a killer and you’re out there, then this office and other law enforcement offices around the country may be coming for you.”

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.