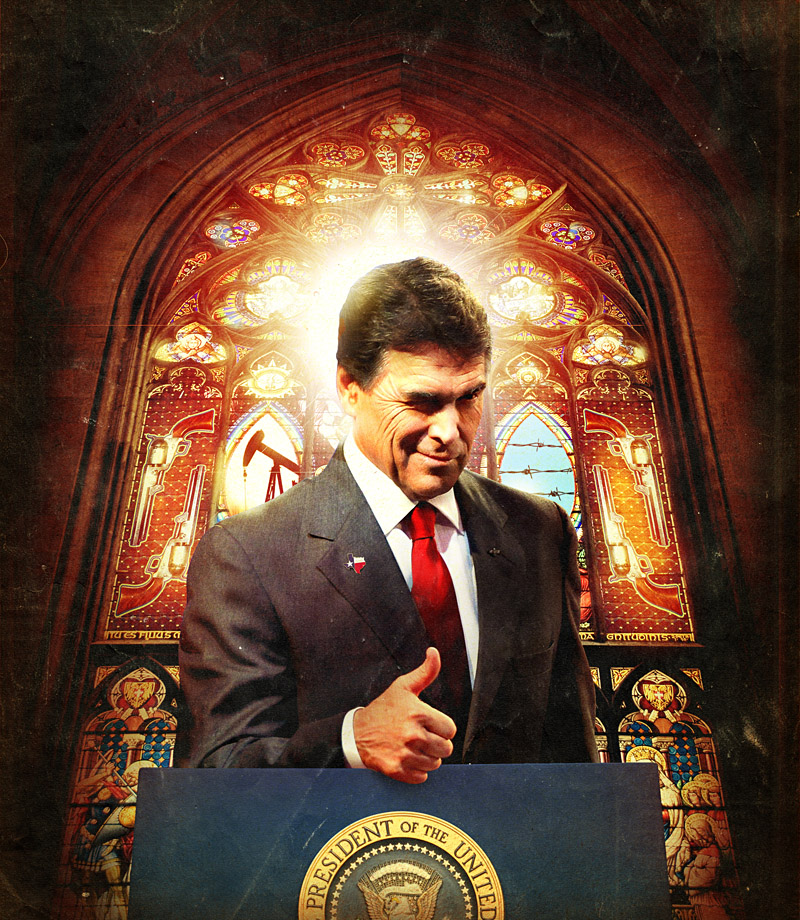

In his quest for the presidency, Texas Governor Rick Perry says three things: His state’s economy is better than America’s. Low taxes and small government are the reasons. He gets the credit.

Almost none of that is true.

The Texas economy isn’t stronger than the national economy, and it may be fundamentally weaker. Poverty is increasing much faster in the state than it is across the country. Despite Perry’s chief campaign message—thanks to him, Texans have damn near too many jobs to go around—unemployment in the state isn’t bucking any trends. In fact, it’s at an all-time high.

Perry’s narrative is attractive from afar but crumbles on close inspection. And its foundation is just as wobbly. When the Republican contenders (and the media covering them) talk about taxes, it’s not a matter of if Texas’ are low, but how low they are—and whether Perry played any role in making them that way. But lost in that concession is the fact that Texas’ taxes are not, on the whole, among the country’s lowest. At best the state’s in the middle of the pack in terms of the actual tax burden on its citizens, and it’s actually more expensive than most in business taxes. He’s right that it’s a small-government state: lots and lots of small government.

As for that government-is-the-enemy card he keeps playing: Perry’s personal political biography includes episodes of naked disdain for local prerogatives, leaning instead toward a top-down governance style that at times has alienated both farm folks and city dwellers, including some Republicans.

But critics who don’t know Perry well, including those obsessing over his recent oratorical flubs, have said one thing about him that is not true, according to those who have faced him in battle: He’s no lightweight. Enter the ring assuming that and you could wind up on the mat counting stars.

“When we see him govern, he’s awful,” says Jason Stanford, a campaign consultant who ran former Democratic congressman Chris Bell’s unsuccessful race against Perry for governor in 2006. “But when we see him campaign, he is a genius.”

You’ve seen it by now, on the campaign trail or at the debate podium: Perry cocking that cowboy smile and vowing to “get America back workin’ again.” He will do it by making Americans more like Texans, who are not, he says, “over-taxed, over-regulated, and over-litigated.” In Washington he will force government to do what he claims he made it do in Austin: “Get out of the way and let the private sector do what the private sector does.”

It’s a powerful 10-second pitch. Of course, smart, well-paid wonks employed by his opponents are working hard to create a good 10-second anti-Perry pitch. But the truth about Perry’s “Texas miracle” can’t easily be packaged in a sound bite.

At the heart of Perry’s so-called miracle is his state’s edge in job creation. He cites U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers to show that Texas has added a million jobs during his nearly 11-year tenure as governor, while the national economy shed 2.45 million jobs. On the surface, it seems like a slam dunk.

But those numbers, heavily cherry-picked for effect, are where the wonks will go when the wonks get going. Perry’s cheery picture ignores a darker story line in which unemployment under his regime has increased much faster than the national rate. It’s now at a 24-year high, putting Texas at mid-pack among the states.

Perry’s favorite window in time is from June 2009 until now—”since the recession ended,” if you believe it ever did. He keeps saying Texas produced 40 percent of all the new jobs in America during that period, and the BLS numbers back that up. What Perry doesn’t say is that in that time frame, Texas unemployment increased from 7.7 to 8.5 percent—the highest since the devastating 1987 Texas oil-and-gas bust—while the national unemployment rate dipped from 9.5 to 9.1.

How did Texas add jobs and suffer greater unemployment at the same time? By growing its population. During Perry’s tenure, the state’s population has grown at more than twice the national rate, the larger share of that growth coming from the birthrate—in other words, not only from folks flocking down to Texas for all those jobs Perry’s allegedly making. New jobs in Texas have not kept up with new Texans.

Bernard Weinstein, an energy economist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and a consultant to national corporations and associations, says the Texas climate is more business-friendly than the national one, and he gives Perry credit for being “a good steward of Texas values.” But even Weinstein balks at giving Perry credit for the state’s economy. Much of Texas’ good fortune, he says, derives from what the rest of the country has been doing for the past 50 years.

Texas is in the middle of the country,” Weinstein says. “That used to be a liability. Now it’s an asset. As the population has moved west, as we have developed highways and air corridors and air conditioning, all of a sudden instead of being in the middle of nowhere we’re in the center of everything.”

These major demographic shifts, continental in dimension, have provided Texas with significant windfalls, Weinstein says. For Perry to claim credit for these is like a drum major strutting in front of the circus parade and pretending he’s the one deciding where to turn.

“At least for the last 40 years, Texas has led the nation in population growth and job creation,” Weinstein says. “So if there is a Texas economic miracle, it started long before Rick Perry.”

Does saying that Texas is “business friendly” mean the state is unlike the rest of the country in some significant way, something important enough to make Texas more prosperous than America? Academic studies and the testimony of people involved in shaping the state’s economy say no. Instead, Texas is much more like the rest of the country than it used to be, but maybe a little worse at being that way than others.

Since the financial collapse of 1987, Texas has been doing what everybody else has been doing: seeking new high-tech and information-based industries, in large part by investing in public education and research. Not only does Perry not get credit for that effort, but his critics, and even some of his friends, worry that he is presiding over a Tea Party–inspired dismantling of it.

Texas used to be different, but not in a way many people in the state remember fondly. The collapse of the state’s economy in the late 1980s laid bare a parochial business climate that had failed to keep its own house in order. In the run-up to the crisis, local banks took cash from an oil boom and used it to play real-estate poker. Many bad bets were made. When the bubble burst, almost all the locally owned banks in the state’s major cities collapsed, and real-estate values disappeared into the dirt. It was a sobering time.

After the bust, Weinstein says, talk shifted to the state’s need to diversify, to get off the oil and real-estate bottles. Looking back, he says the devastation wrought by the bust sort of took care of the diversification issue on its own. “The economy diversified itself,” he says, “because as energy and real estate and agriculture shrank, the state’s economy de facto became more diversified.

“In attempting to diversify, though, Texas became much more like everybody else in terms of public policy. There was “a rush to the adoption of public policies to stimulate economic growth,” Weinstein says. “So we got legislation in Austin allowing local government to give away tax base.”

Prior to the energy bust and the real-estate collapse, we didn’t have things like economic-development sales taxes and property-tax abatements, emerging-technology funds, the Texas Enterprise Fund,” he says of states’ efforts to lure companies across their borders. “We didn’t do that stuff. A lot of other states did, but we didn’t, because, number one, we never needed to, and number two, well, gosh, that’s state socialism. But nonetheless we started doing all that stuff.”

In its pursuit of new industries, the state didn’t just give tax money away. It also levied record-high new taxes and put the new revenue into public education and university research. At roughly the same time, an important court ruling forced the state to share education funding more equitably among rich and poor school districts.

Paul Colbert, now an education consultant in Houston, served in the Texas legislature with Perry in the late ’80s and early ’90s. He points to a legislative session in 1987 in which Perry—then still a Democrat—joined a majority in both parties in passing a record-setting tax increase. With that money, Colbert says, “we did several things that turned the economy around, intentionally. One of them was that we didn’t cut funding for public education.

“Number two, we made a conscious effort to focus on payments to higher education in the areas of research funding—in particular in the areas of creating spinoff from university research and economic development that basically resulted in creating what they now refer to as the Silicon Hills of Austin.”

As a result, companies started moving headquarters or significant operations to the Austin area, including Dell Computers, Nvidia, 3M, and Apple Inc.—so many that the direct American Airlines flight from Austin to San Jose, Calif., now discontinued, was called the “Nerd Bird.”

The state’s investment in education paid off in other ways. Texas public-school students made significant strides on achievement tests. “If you go back to the early 1990s,” Colbert says, “there was a RAND study, the first of a number of RAND studies that indicated that Texas had basically jumped well ahead of the pack in education. If you went demographic subgroup by demographic subgroup, we were well ahead.”

Texas has not remained faithful to these efforts under Perry. Lawmakers in recent years have relentlessly dialed back support for public education and devised ways to escape court-ordered revenue-sharing for poor districts. Some of the big test-score gains of the ’90s turned out to be based on cheating. Achievement seems to be headed south. And that was all before this year.

In this year’s legislative session, Perry proudly led the call for $5.4 billion in cuts to state support for public education, leaving the state education budget at $29 billion, according to an analysis by the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts. Before these cuts, the nonpartisan Texas Legislative Study Group placed Texas at 47th among the states in support for education, and 50th in the percentage of the population 25 and older with high-school diplomas.

Perry’s supporters argue the cuts were necessary to deal with a two-year state budget deficit projected at $15 billion to $27 billion, depending on who’s projecting. His detractors wonder why a state that’s supposed to have the nation’s most robust regional economy lumbers under such shortfalls. They also wonder why a supposedly healthy economy produces a poverty rate 20 percent higher than the national rate, according to census data released last month.

Regardless, the state’s government, like state governments elsewhere, was headed for the poor farm if something didn’t get cut. Perry, with strong backing from Tea Party–right majorities in both houses of the legislature, focused on public schools with a vengeance. The state cut support for schools by $500 to $700 per student and completely gutted two areas considered vital to minority student success: full-day pre-kindergarten and a series of grant programs for tutoring and other special support.

In championing the cuts, Perry staved off calls to take more from the state’s $9 billion “rainy day” fund, which many said was established for just such a purpose. That move lent credence to critics who believe Perry’s real purpose was a Tea Party–friendly “starve the beast” strategy to diminish public education as a communal responsibility.

These cuts, all so public and brash, have actually elbowed out of the headlines another Perry initiative that may worry the Texas business and research communities even more.

In 2008, Perry convened a “higher education summit.” At it, he unveiled his ideas to make it easier, cheaper, and faster for students to graduate from the state’s top-tier universities. His “seven breakthrough solutions”—actually the handiwork of a former oilman and friend, Jeff Sandefer, who has donated $300,000 to Perry’s campaigns since 2000—would forbid universities from using academic research to decide whether to grant professors tenure.

Under the plan, which is nowhere near adoption, tenure decisions would depend heavily on “customer satisfaction ratings”—grades students give teachers. A professor would have to show that he or she has been teaching at least three classes of 30 or more students every semester for seven years, earning customer satisfaction ratings of at least 4.5 out of 5 possible points.

People who feel they helped bring the Texas economy back from the debacle of 1987, even some who are friendly to Perry otherwise, are horrified by Perry’s “seven points.” “To me, it’s a disgrace to the tradition of scholarship and discovery,” says John Sibley Butler, a professor of entrepreneurship and small business at the University of Texas at Austin and director of an institute that studies and promotes economic growth in Texas.

Weinstein, at SMU, served as a consultant in the late ’80s to cities trying to attract high-tech industry. In retrospect, he says, those glad-handing recruitment campaigns probably had less to do with drawing high-tech businesses to Texas than the presence of well-funded and prestigious academic research centers. “I think more of that has come about as a result of the research that occurs in a place like the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, which is one of the largest medical complexes in the country,” he says. “UT Southwestern has probably generated a lot of spin-off activity and attracted a lot of health-care companies to the region.”

For all Perry’s Texas swagger, there are simply ways in which he doesn’t get Texas, says Texan Terry Sullivan, a political science professor at the University of North Carolina. “The reason we don’t have kudzu in Texas is because researchers—not teachers, but researchers—at Texas A&M University know how to stop that stuff,” says Sullivan, a national fellow at the Hoover Institution, executive director of the White House Transition Project, and editor of The Nerve Center: Lessons in Governing From the White House Chiefs of Staff. “The reason our cattle are more productive in Texas, even though they live on really crappy land, is because researchers, not teachers, at Texas A&M discovered how to make cattle stronger.

“For somebody to think that major state universities like Texas A&M should focus on teaching and not research is to grossly misunderstand the importance of fundamental research to the economy of the state of Texas. So if a governor’s only claim to fame is his ability to improve the economy of Texas and he doesn’t get that, then there must be a critical difference between how the Texas economy got where it is and that governor’s role in it.”

If the state’s relationship with education and research has appeared a little schizoid—here, take the money; no, give us back the money—what effect has all that had on the hardiness of the overall Texas economy? It’s hard to draw direct links, but the available studies suggest it’s not nearly as robust as Perry depicts.

An October 2005 analysis by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas looked closely at how Texas recovered from the post-9/11 recession. They concluded that the Texas economy was significantly slower to heal and more jobless in its rebound than the national recovery, for a variety of reasons.

Perry’s critics often say he benefits from all that “oil in the ground,” but oil and gas jobs have waned. Meanwhile, a wider shift from manufacturing to government employment—especially all those education jobs added before Perry helped gut them—required major retraining of laid-off workers. According to the Fed study, that shift left the state’s economy more susceptible to the punch it’s taking now, and to the roundhouse of the recession’s potential double-dip. But in the end, the report called Texas’ poor performance in overall job creation “a bit of a mystery.”

It was less mysterious in a report published two years later by the conservative Kauffman Foundation. The group’s “New Economy Index” measures growth and innovation in information technology. It examines an array of measures—patent applications, initial public stock offerings, immigration of knowledge workers, workforce education, and other indicators—to see where the new technology economy is hot and where it isn’t.

Of the 50 states, Texas earned a second-tier overall ranking in the 2007 report—14th place—but with low marks in the areas of workforce education (34th), high-tech manufacturing (35th), and desirability as a destination for knowledge-industry immigrants (44th). The 2010 version reported that Texas had slipped from the 2007 overall national ranking of 14th place to 18th. And while Texas got a much better mark as a home to high-tech manufacturing, moving up from a national rank of 35th four years ago to 10th in 2010, Texas’ overall rank was dragged down by rankings in the 40s in two key areas: workplace education and the immigration of knowledge workers.

What if Perry’s critics are right? What if a strong public-school system and prestigious university research programs were keys to Texas’ economic success? If those legs of the Texas miracle are being sawed off, what’s left?

Another important plank in Perry’s Texas-miracle platform is his portrayal of Texas as a low-tax state. As he tells it, low state and local taxes are what are drawing businesses and people to his state. Like so much in Perry’s portrait of Texas, the notion may be more wishful than real.

Weinstein, at SMU, now confines himself to the economics of energy, but for 25 years he was the state’s best-known business recruitment and expansion consultant, hired by cities all over Texas. During that time, most tax incentives in Texas amounted to the state government’s granting local governments permission to give away their own tax bases to woo companies. It’s a practice Weinstein now questions. “All the research on economic development I’m familiar with over the last 60 years has found that state and local incentives are a fairly minor factor in the business-site-selection calculus,” he says. “And that’s understandable, because state and local taxes for a lot of companies are fairly minor costs of doing business.” Plus, he says, “every other state does the same thing.”

But, as Weinstein points out, cutting those local taxes can hurt the localities that do it. “[Those businesses are] still going to have kids in school,” he says. “They’re still going to need the roads and the water. Somebody else has got to pay for the cost of providing services to that business that isn’t going to be paying its fair share of the taxes.”

Despite the giveaways, small government still doesn’t mean scant government in Texas. It means lots and lots of small government and accompanying taxes. Sure, a new Texan might relish the paycheck bump from the state’s lack of income tax. But a typical Dallas property owner pays property taxes to the county, city, local schools, county hospital district, county educational-services district, and community-college district, along with sales taxes to the state, sales taxes to the regional transportation agency, and a plethora of local, county, regional, and state fees and excise taxes.

In addition, a host of new tax-related entities, mainly invisible to the public, has been created in the past 25 years, including municipal utility districts, tax-increment financing districts, redevelopment zones, municipal management districts, and more, most of which have the power to borrow money, all of which must be repaid by taxes.

So is Texas truly the low-tax state Rick Perry paints it to be as compared to the other 49? Judging by the few available comprehensive surveys, the answer is one that should be familiar by now: No.

The Council on State Taxation (COST), which represents large corporations on state tax issues, hires the accounting firm of Ernst & Young every year to study total state and local business taxes. Their 2010 study puts Texas at 19th among states with the highest business taxes as a percentage of gross state product.

The Tax Foundation, a conservative think tank, gives Texas good marks for its total state and local tax burden per capita—39th place, with 50th marking the lowest tax burden. But the Tax Foundation ranks Texas fifth-worst for corporate taxes, a ranking that reflects a plethora of excise, licensing, and other costs, taxes, and negative incentives that businesses must deal with in Texas. The state also claims the third-highest effective property-tax rate in the country after New Jersey and New Hampshire, according to the Tax Foundation.

The shifting of public responsibility from state to local government also shows up in the study’s rankings for total public debt per capita. If you look only at state government, Texas looks great—the next-to-lowest debt per resident in the country. But when you add local debt to that state debt, Texas falls into 15th place, among the most debt-loaded states in the union.

Taken together, the numbers fail to conform to Perry’s portrayal. In job creation and economic hardiness; as a tax haven; even as a place where government is supposed to be scarce, Texas fails to fit the sound bites. Which raises another obvious question: Perry himself. If Texas is not the small-government, low-tax, bottom-up-governed oasis its governor describes, is he even that kind of leader?

The Tea Party has been lighting torches of discontent in recent weeks over Perry’s support for in-state tuition for children of illegal immigrants (too compassionate) and his backing of mandatory HPV vaccinations for sixth-grade girls (too progressive). But another chapter, one too nuanced for the 24-hour news cycle, better demonstrates Perry’s true style of governance: his failed attempt to create a high-tech transportation corridor across the entire state.

Announced in January 2002, the “Trans-Texas Corridor,” or TTC, was to be a gigantic 4,000-mile swath, 1,200 feet wide, carrying high-speed rail, pipelines, and high-tech super-toll roads from Mexico to Oklahoma. Like the higher-education “seven points” plan, the TTC was the brainchild of a millionaire pal of Perry’s, the late Ric Williamson, whom Perry had appointed chairman of the state’s Transportation Commission.

The problem, according to people involved in Texas transportation and trade issues at the time, was that Perry and Williamson dropped the plan on legislators as a fait accompli, without any political preparation. Then they made things worse by stubbornly trying to force it by fiat down the throats of an increasingly recalcitrant citizenry.

The TTC idea is dead now, shot many times in the head by the legislature. After Perry unveiled the TTC in 2002, farmers, small towns, and two major cities rose against it in horror, fueled by its threatened use of eminent domain and a backroom deal to turn the road over to a Spanish toll-road company—without a bidding process. Even worse, the preordained route would have bypassed, and probably killed, major new shipping centers in both Dallas and Fort Worth.

State Senator Florence Shapiro, a Republican powerhouse, still thinks the basic concept may have had merit. She calls Williamson, who died of a heart attack four years ago, “a very, very bright man.” But, she says, “The manner in which it was presented was the problem. They didn’t even try to work it out. They just said, ‘Here’s the plan.’ “

The TTC is hardly the only example of Perry’s ham-fisted governing style. After the savage bloodletting of the most recent legislative session, he poured salt in the wounds of local school districts by seeming to blame all the unpleasantness on them: “The lieutenant governor, the speaker, their colleagues aren’t going to hire or fire one teacher, as best I can tell,” he told reporters at a news conference. “That is a local decision that will be made at the local districts.”

Well, yes, because Perry and the legislature cut off their money.

Perry also vowed publicly that he was not forcing his “seven points” anti-research plan on any of his many appointees to Texas university boards of regents. He said he had presented the plan to them merely to foster discussion. “I appoint people to the board of regents,” Perry said in May 2008. “They are in charge of setting policy . . . that’s their call. It’s not the governor’s call. It’s never been the governor’s call, and I don’t get confused about what my role is.”

But in April 2008, the Houston Chronicle published e-mails sent to regents and university chancellors by Perry aide Marisha Negovetich in which she repeatedly hectored them to get going on the governor’s “seven points” plan. “The Governor is anxious to put together a cohesive plan of action . . . and also learn from you what progress you have made to move these reforms forward,” she wrote.

In the September 12 GOP presidential debate, Perry said he was “offended” by criticism from Minnesota congresswoman Michele Bachmann that he “could be bought for $5,000” from Merck, maker of Gardasil, the HPV vaccine that Perry mandated by executive order in 2007 for all Texas girls entering sixth grade. Two days later the Houston Chronicle‘s Austin bureau laid bare a pattern of six-figure contributions by Merck to a middleman fund that has given millions to Perry.

Stanford, the campaign consultant Perry beat in 2006, agrees Perry botched the Gardasil moment, but he says it also illustrates why he might get himself elected president. The same traits that make him tone-deaf in office, Stanford says, can make him pitch-perfect on the campaign trail. Before Perry unleashed his Gardasil order, Stanford says, “He hadn’t done that hard government work that you have to do in building coalitions. He hadn’t reached out to the people who already agreed with him and gotten them on board.”

Stanford ticks off a roster of state and national women’s organizations, concerned over the link between HPV infection and cervical cancer, that had been calling for universal HPV vaccination for years. “He could have, in a government way, reached out and said, ‘Here is a bipartisan coalition for this idea. Let’s all talk about this idea.’ But no. One day, boom, he announces it. No coalition.”

Stanford calls that lousy governing. But he says it can also be “a great way to do a campaign.” He says Perry’s style—grand gestures, few details—is the right kind of theater for an election. “You surprise everyone. Everyone’s looking at you. You own an idea.” That’s just how Perry rolls, Stanford suggests. “He likes surprising people with big ideas.”

On the campaign trail, Perry still has the gestures and body language of the handsome country bumpkin who was elected a yell leader at Texas A&M in 1970. A&M, newly coed, was still more military academy than college when Perry, a poor ranch boy from a flyspeck town 180 miles west of Dallas, showed up in 1968 wearing shirts, pants, and underwear sewn by his seamstress mother.

Yell leaders then, as now, were more like orchestra conductors than cheerleaders, directing the A&M bleachers at football games in “army yells” communicated by coded hand signals. It’s an elective post, a popularity contest that garners twice the voter turnout as the school’s election for student body president.

Watch Perry’s appearance on The Daily Show from last November, and you’ll see him wrest the audience away from host Jon Stewart at key moments, with sly grins sidelong to the peanut gallery and, yes, even a hand signal or two. The man does know crowds.

“What he has more than anything else is street smarts,” says Colbert, the education consultant and former legislator. “What he has is an ability to be able to judge people for what it is that’s important to them. How can I make them my friend? In all sorts of ways that’s a very, very important skill to have, and if you happen to be in politics, it’s one of the most vital skills you can have.”

He’s particularly adept at picking up on and hooking into important underlying themes in public sentiment long before other politicians get a clue, Colbert says. “He sees it. He runs in front of it, and regardless of whatever his underlying stuff may be, he will do what he needs to do to stay on top of that wave rather than have the wave roll over him and crush him,” Colbert says. “He’s a good surfer.”

That’s exactly what Stanford says he saw Perry do to Kay Bailey Hutchison when he beat her in the 2010 Republican primary. That April, when country-club Bush Republicans were still looking down their noses at the Tea Party, Perry spotted what Stanford calls “the simple campaign algebra” and ran with it.

“He’s down by a couple dozen points against this really popular lady,” Stanford remembers. “He figures his only chance really is to say she’s Washington. And then suddenly the pitchfork crowd comes up and says, ‘We hate Washington.’ ” Stanford says Perry’s quick response was “‘Oh, cool, here’s my army. I shall lead them.’

“Before any politician in the country was willing to talk to the Tea Party,” he says, “he spoke to three of their rallies in one day. He was the only guy in the country. He saw the train coming down the tracks that he knew he’d have to take.”

To these personal gifts another important asset must be added: a campaign staff so brilliant it’s already being studied by political scientists across the country. In an excerpt from his book, Rick Perry and His Eggheads, journalist Sasha Issenberg explains how the Perry gubernatorial campaign in 2010 allied with a team of political scientists from Yale, the University of Texas at Austin, and the University of Maryland.

And then there’s the pure weirdness of Texas, and Perry’s ability to exploit it. Stanford says Perry has whipped a succession of candidates who may have been smarter than he was about the world because Perry was smarter than they were about Texas.

“Rick Perry always knew that to be Texas governor, first in the voters’ eyes you had to be Texas,” Stanford says. “He did an ad campaign, ‘I’m proud of Texas, how about you?’ If you’re attacking Rick Perry, you’re attacking Texas. He always sets it up that way.”

Perhaps the last question, then, is whether being proud of Texas can get Perry elected president.