Ricardo Cruz Mejia’s final days began with a stomach problem. It was October 2010. After the 26-year-old Walla Walla State Penitentiary inmate discovered blood in his stool, he signed in at the prison infirmary. A test and exam turned up a severely inflamed colon. The onetime Latino gang member from Skagit County, doing 34 years for seven felonies including murder, was given hydrocortisone enemas and tabs of prednisone, used to treat inflammation. The prison medical staff also gave him sulfasalazine for abdominal pain.

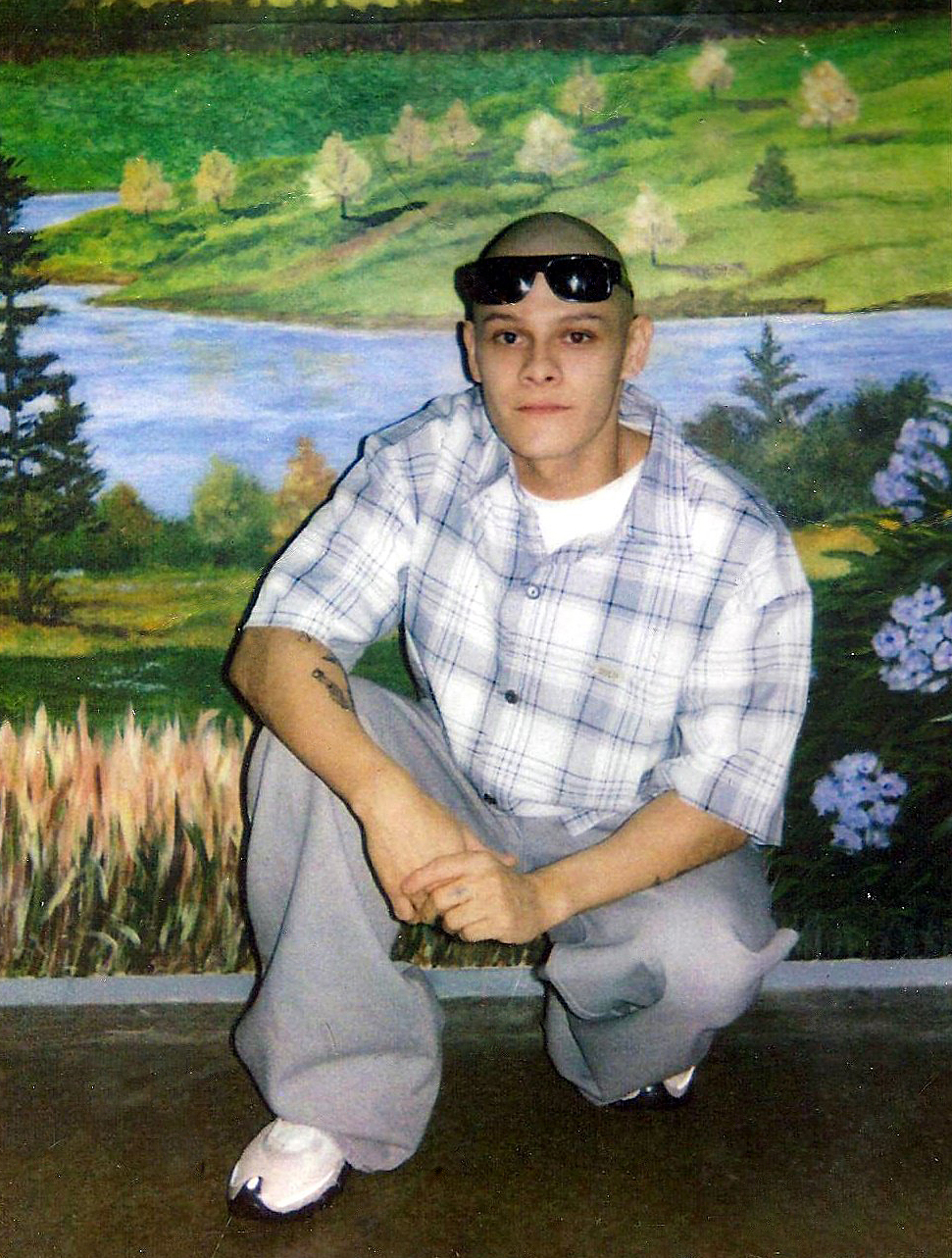

In November, Mejia, a stocky, tattooed inmate with a closely shaved head, began to experience other symptoms—headaches, sore throat, then vomiting. He also had begun to develop a rash, for which he was given penicillin, though it didn’t seem to help.

In the ensuing days, he became a familiar figure to infirmary nurses. From December through the first week of January 2011, he showed up at the infirmary 14 times. Nurses doled out a topical corticosteroid for skin inflammation and tried other drugs to ease his symptoms. Still, none alleviated the persistent, painful irritations and stomach problems.

On January 10, 2011, he arrived to tell medical staffers his sore throat was killing him—“It hurts to breathe,” he said, according to notes in his medical record. Staffers seemed stumped. His vital signs weren’t taken and no new treatment was offered.

Mejia returned the next day and announced he was having what he called “a medical emergency.” In addition to his earlier symptoms, he had developed fever blisters, sore joints, and rectal pain. His pulse was racing, his blood pressure rising. He had been unable to eat for three days, he said.

Prison physician Barry Kellog, who examined him, did not find Mejia in any acute distress and prescribed more prednisone and sulfasalazine. He’d later recall he saw Mejia only briefly, and was not informed by the nurse who was assisting him and had treated Mejia earlier that the patient turned out to be allergic to sulfasalazine. Nor did she tell him, Kellog recalled, that Mejia had a rash and had been diagnosed with colitis, an inflamed colon.

…inmate Ricardo Mejia—a patient who’d been denied admittance to the prison infirmary 16 hours earlier—was pronounced dead.

On January 13 at 8 a.m., Mejia was back complaining of similar problems, and a new one—blisters on his anus. He was examined and given an oral antifungal.

The next day, Mejia returned—this time with painful mouth and rectal ulcers and severe abdominal pain. He’d been unable to have a bowel movement for four days, he said. He was given hydrocortisone, milk of magnesia, and an anesthetic. A nurse provided moistened gauzes to place on the painful skin ulcers.

Nurse Allison Oleson would later say that it was clear Mejia was “quite sick” that day. “When this kid came into the exam room, he was clearly in distress.” She said she called on Kenneth Moore, a physician’s assistant, to take a look at Mejia. (Known as PAs, the assistants are not accredited doctors but practice medicine on a team under the supervision of physicians and surgeons; typically they are formally educated to diagnose illness or injury and provide general treatment).

But Moore, like the earlier doctor, did not examine Mejia, Oleson recalled. He didn’t even see him. During a phone chat with the nurse, he ordered Lidocaine, a topical pain-numbing gel.

Mejia returned to his cell. But his symptoms grew worse. At 4:30 the next morning, January 15, a medical staffer who visited Mejia in his cell undertook a brief examination and told him to come into the infirmary a few hours later.

When the inmate showed up at 7:30 a.m., he was seated uncomfortably in a wheelchair. He was unable to sit and was experiencing diarrhea. His pulse, temperature, and blood pressure were all rising and his buttocks were red with blisters.

At 8:45, Moore, the PA, agreed to examine him. But he initially decided not to admit Mejia to the prison’s inpatient unit. Pressed by nurse Vickie Holevinski, who recognized signs of sepsis—indicating Mejia was suffering from widespread infection with a threat of multiple organ failure—Moore relented.

Mejia was treated with antibiotics and given whirlpool baths. Still, two and a half hours into treatment, he was breathing rapidly, and his blood pressure had plunged while his heart continued to race. He had skin excoriations over much of his body, particularly down his legs and around his buttocks. In some places, his skin had broken open, turned purple, and was draining. He was dizzy and in pain, he told nurses, and suffering from shortness of breath.

Faced with clear indications Mejia was in danger, PA Moore decided he needed to go to an outside hospital. At 1 p.m. on Jan. 15, 2011, an ambulance ferried Ricardo Mejia downtown to Walla Walla’s Providence St. Mary Medical Center. It would be his last day in prison. And his last full day of life.

St. Mary doctors, finding a severely ill man in their emergency room, began running tests. Within a short time, they concluded Mejia, now in shock, needed specialized emergency care they were not equipped to deliver. He was a stretcher-ful of ailments, including perianal cellulitis, proctitis, sepsis, and ulcerative colitis. Most crucial, doctors discovered necrotizing bilateral tonsillitis. A flesh-eating disease had set in.

Doctors alerted the state medical airlift service, and Mejia was hurried to Walla Walla Regional Airport and put aboard a small plane. By 6 p.m. he was in the air, flying over the prison, headed to Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center in Spokane, one of the region’s biggest hospitals and specialty-care centers.

Alerted in advance, Sacred Heart doctors were ready when Mejia was wheeled in. He was immediately prepared for surgery, and doctors realized they’d have to cut away infected sections of his body. He had Fournier’s gangrene, a critical infection of the genitalia. Capable of developing quickly, within hours, it causes severe pain in the penis and scrotum and progresses from a spreading redness to necrosis—the death of tissue.

That and contributing conditions were also causing Mejia’s kidneys to shut down. The medical team had no alternatives in surgery, and began removing his rectum and large portions of his buttocks.

It was a long, challenging debriding of the infected areas. And it came too late. At 2:02 the next morning, Jan. 16, 2011, state inmate Ricardo Mejia—a patient who’d been denied admittance to the prison infirmary 16 hours earlier—was pronounced dead.

Mejia’s death didn’t make the news. But it mattered to his family, at least, including his two children by separate mothers in Skagit County, and his surrogate mom, as April Soria calls herself. A counselor in a Skagit work-training program, Soria first met Mejia—whom she calls “Richard”—when he was a teen in trouble. Born a U.S. citizen, Mejia was abandoned by his birth mom when he was young and raised by others, spending much of his time on the streets. Young Mejia came to confide in Soria, and the two struck up a familial relationship. As his designated outside prison contact, she was first to get the bad-news phone call from Spokane early on the morning he died.

“It was the hospital chaplain,” Soria recalls. “At first I didn’t know he was saying Richard had died. I couldn’t understand what this thing was that had happened. Then he said—I can’t forget the words—‘This is the worst case of medical negligence we’ve ever seen.’ ”

In September of 2007, Mejia, then 23, was sought for burglary, assault, car theft, and eluding deputies.

But, as Soria would find out, it happened within a system not prone to publicize its mistakes or generate public sympathy for its inmates. After all, Mejia, a onetime street gangster known as Li’l Jokes, entered prison with 17 felonies on his record. He’d already done a two-year prison stretch for discharging a weapon in public during a Mount Vernon gang dispute in 2005. In 2009, he was returned to custody, this time sent to the hard-time Walls for a string of crimes including the murder of an elderly woman.

In September 2007, Mejia, then 23, of Sedro-Woolley, was sought for burglary, assault, car theft, and eluding deputies. With two female accomplices, he was looting a home outside Burlington when the homeowner walked in. The three fled in a car and eluded police in a mad chase, hitting speeds of up to 90 mph and crashing the car in a cornfield. The women were nabbed but Mejia got away, running to a nearby home.

There he encountered an 84-year-old woman named Clara Thorp and demanded her car keys. She had no car. An enraged Mejia pushed the frail lady to the floor and ran to a second home nearby, where he was able to commandeer a car and escape. Officers found that car crashed in west Mount Vernon, but Mejia was gone again. Two days later, attempting to break into a vehicle in Mount Vernon, he was spotted by an officer. After a standoff in which Mejia climbed a structure and resisted arrest—he was Tased six times in a struggle—police took him into custody.

Three months later, the elderly woman died. Clara Thorp had been on the floor, undiscovered, for more than an hour, and was hospitalized with a broken pelvis. A few days later she also suffered a heart attack. She ended up disabled, living in a senior care center, turning 85, and never regaining her health. On Jan. 11, 2008, she died from pneumonia stemming from her injuries, the medical examiner ruled, labeling the death a homicide. By law, a death that occurs during the commission of a felony can be charged as a murder. Skagit prosecutors therein refiled 14 felony charges altogether against Mejia, including first-degree murder, accusing him of exhibiting “deliberate cruelty” in his attack on the defenseless Thorp.

Mejia, who faced the possibility of life in prison, mulled over his chances as the case dragged out for a year. Soria, his adopted mom, says “I told him, ‘You have to plead guilty.’ He didn’t intend to kill her. But he had to take responsibility for what happened.” Mejia agreed to a plea bargain. The case was winnowed down to seven felonies and the murder charge dropped to second-degree.

In June 2009, Mejia was sentenced to 34 years. “For a 24-year-old man, this criminal record could be the biggest one I’ve ever seen,” said Skagit County Superior Court Judge John Meyer, according to a report in the Skagit Valley Herald. Clara Thorp’s son, granddaughter, and great-grandson were in the courtroom and read a statement about Thorp’s assault and death, recalling the agony of having “watched her go through so much pain she didn’t deserve.”

Mejia, contrite, apologized for his life of crime, drugs, and gang-banging. “I know I’m a monster,” he told Thorp’s family. “I know you guys hate me. I hate myself for the things I’ve done.” Says mom Soria: “There was never a minute, from the day of her death to the day of his death, that he wasn’t sorry for what he did.”

As a career criminal, Mejia wasn’t a likely candidate to change his life by doing another prison stretch. Still, he had hope: If he’d completed his full term and been released, he’d have been 58. At least he wasn’t a lifer, nor had he been condemned to death.

Not officially, anyway. As it turned out, Mejia, like his victim, went through pain he didn’t deserve, serving a capital sentence he wasn’t given. Unlike Clara Thorp’s, however, no one would be punished for his death.

“Charlie Manning, doing 13 months after a drunken argument with a neighbor, left prison with no penis.”

An autopsy ordered by the state determined Ricardo Mejia died of blood poisoning and septic shock resulting from the flesh-eating disease and rectal infection. The death raised concerns at the state Department of Health, and inspectors began perusing prison medical records and asking questions.

In a May 2011 report, the department found the prison had failed to provide “a formalized process for continuity of care and supervision.” Medical staff was not prepared, and supervisors were missing in action. There was only informal oversight of mid-level care providers, such as physician’s assistants, and a lack of case discussion between line staff and the prison’s medical director, Dr. James Edwards.

In Mejia’s case, nurses had repeatedly failed to obtain his vital signs or contact the on-call doctor or PA when those signs were out of whack—and even then there was a lack of urgent response, investigators found. On January 15, the day Mejia ended up being rushed to the hospital, the nurse visiting his cell that early morning recorded his heart rate at 154—and merely made an appointment for him to see a doctor three hours later. Help should have come immediately.

To critics of the prison medical-care system, the Mejia case sounded eerily familiar. In 2004, Charles Manning, an inmate at Stafford Creek Correctional Center outside Aberdeen, was diagnosed as having an allergenic reaction to Robitussin, the cold medicine. He endured two days of pain in the prison infirmary, treated with an ice pack and medications. He was then belatedly diagnosed with an infection and was transferred to Grays Harbor Community Hospital. There, emergency doctors determined—much as the Walla Walla and Spokane doctors did in Mejia’s case—that Manning had Fournier’s gangrene.

To save his life, the Aberdeen doctors removed his genitals and pounds of flesh. Unlike Mejia, Manning survived. But he was left disfigured and disabled. As Prison Legal News put it in a report, “Charlie Manning, doing 13 months after a drunken argument with a neighbor, left prison with no penis.”

Such cases are costly not only to the victims but to taxpayers—Manning, for example, later sued for damages, accepting a $300,000 settlement from the state in 2008. (In one of the most costly state cases, Gertrude Barrow, 41, died at the Washington Corrections Center for Women in Purdy of a perforated chronic peptic ulcer and acute peritonitis. In 1994, her family was awarded $630,000 due to state negligence).

“Prison doctors are not necessarily going to be the best practitioners available,” Paul Wright says in a purposeful understatement. “The state DOC has a long history of employing doctors with disciplinary histories and not sanctioning them even when they kill, and keeping them on the payroll.”

And Wright would know. Some of those doctors treated him. Wright was a state prison inmate for 17 years, convicted of the murder of a drug dealer. Among those who tended him was a dentist named Joel Driven. In one example of his care, according to state investigators, the 72-year-old dentist wrenched out part of a McNeil Island inmate’s jawbone rather than the tooth he intended to pull. That tore open the roof of the inmate’s mouth, causing Driven to panic as the prisoner faced the likelihood of bleeding to death. A second dentist also froze, as did a dental assistant. Another assistant saved the day, taking over Driven’s patient, shouting commands to the doctor, and calling for emergency aid. She told investigators that what she’d witnessed was “torture . . . barbaric.” In 2007, Driven was let go and his license revoked.

Wright, who served his time and went on to found Prison Legal News and campaign for prisoner rights, says the 10-year-old Manning case should have been a turning point for corrections medical reform. But “Whatever they did [after that settlement], if they did anything, obviously didn’t help Ricardo Mejia.”

Wright’s umbrella organization, the Human Rights Defense Center of Lake Worth, Florida, got interested in Mejia’s case. Started on a $50 budget with an all-volunteer grassroots base, the center has today become a 501(c)(3) organization with 10 full-time employees including three staff attorneys. It specializes in litigation and advocacy for prisoners.

“Manning was crippled and Mejia killed because of the sheer neglect and ineptitude of DOC medical staff,” Wright says. “This is an ongoing story with the state DOC.”

It was a story that Mejia’s mom, Soria, wasn’t getting in full, she says. “It was so difficult to get at the truth. The state wouldn’t provide public records. One state records clerk I got to know said, off the record to me, ‘This isn’t normal. These records should be available. You need to get an attorney.’ ” She did.

In April last year, Wright’s defense center filed a legal tort claim for damages against the state for the medical failures leading to Mejia’s death. It was brought on behalf of Soria and Mejia’s two children, ages 12 and 7. Jesse Wing, the lead attorney in the claim, from Seattle law firm MacDonald Hoague & Bayless, says “Mr. Mejia’s case illustrates something worse than inadequate care. He suffered not just incompetent care, but obvious indifference to his serious pain and illness. This ‘I don’t care if you live or die’ attitude is at odds with the most basic duty of a health-care provider and of the Hippocratic oath.”

The claim focuses particularly on the role of Moore, the physician’s assistant who’d been reluctant to admit Mejia as an inpatient. Prison medical director Edwards told state investigators that Moore “tends not to listen to nurses . . . [he] irritates and frustrates” them. Pat Rima, the prison’s former health-care administrator, said Moore was “at times . . . on the edge with his care decisions,” and that at one point she opted not to renew his then-part-time contract. But after Rima moved on to another job, her replacement rehired Moore, with Edwards’ approval, full-time.

One nurse recalled that on the day Mejia would eventually be rushed to an outside hospital, she had repeatedly beseeched Moore to admit him as an inpatient. Mejia had arrived in a wheelchair in great pain, his heart racing. Another nurse said Mejia was so obviously septic he “could go south in a hurry,” yet “Mr. Moore was sitting there, allowing the patient to wait 45 minutes while no treatment orders or medication was given.”

“The DOC spends over $100 million a year on [care] and prisoners still die gruesome deaths from easily diagnosed illnesses.”

About the time the claim was filed, the state Medical Quality Assurance Commission—responding to a separate complaint filed by Wright’s group—lodged charges against Moore, claiming his care may have constituted medical “incompetence, negligence, or malpractice.” He failed to recognize a life-threatening condition, the commission said, and lacked concern when urgency was called for.

Moore didn’t take much time to settle the complaint. And why not? His penalty was to write a paper about his error. In what it calls an informal disposition, the commission ordered Moore to study up on sepsis, colitis, and necrotizing fasciitis, then compose 1,000 words on those topics. He’d also have to make a class-like presentation to others on the prison medical team, and would have to reimburse the commission for costs, $750. “It was a slap on the wrist,” says Mejia attorney Wing.

In January of this year, the charges against Moore were formally withdrawn, although he still must comply with the writing and educational stipulations of the disposition.

That same month, having received no answer to the claim filed against the state, Wright’s group went to court and formally filed a lawsuit against the Department of Corrections on behalf of Mejia’s estate. In the suit, attorneys alleged that Mejia “died a horrible and painful death at age 26 . . . [his] medical providers ignored obvious signs of infection and serious medical illness, and he literally rotted to death.” Timely diagnoses and treatment would have spared his life and the pain he suffered, the suit claims, citing mistakes turned up by the Health Department probe.

Four months later, in April, the DOC agreed to settle.

The department conceded some responsibility for Mejia’s painful death. It agreed to pay $740,000 to his family, likely a record amount in such a case. The department also said it had made some changes in its prison medical operations to comply with the Health Department’s findings, including assigning inmates to doctors, expanding dialogue between staff and supervisors, and informing staff in more detail about flesh-eating bacteria. But the state admitted to no legal wrongdoing in Mejia’s death.

Nonetheless, as in the earlier flesh-eating case, it was a costly mistake in life and money that could have been avoided, says Paul Wright. “The common theme here is the DOC botched the diagnoses until it was too late—and remember, these are deep-tissue bacteria that take at least a week to develop to the killer phase, and as soon as these men were taken to a hospital, the ER doctors diagnosed them almost immediately.

“I think the most compelling story is the bigger issue of inadequate medical care,” Wright says. “The DOC spends over $100 million a year on [care] and prisoners still die gruesome deaths from easily diagnosed illnesses.”

Wright says his organization expects to bring other suits in the future. Unfortunately, he says, there will be a need for them.

As for April Soria, she didn’t share in the settlement. “She is just a very good person who tried to help him and his family,” says attorney Wing, “so the settlement money went to his children.”

Two weeks ago, Moore showed up at a medical-commission hearing to see how he has complied with settlement stipulations. Wing, who also attended, said “a state lawyer told us afterwards that a purpose of the hearing was for the board to see Mr. Moore’s demeanor when discussing care of patients. We pointed out that Mr. Moore’s demeanor did not seem appropriate under the circumstances. He did not show any sense of responsibility for the death of Mr. Mejia or even that he was discussing the death of a human being at the hearing.” But apparently Moore received the state’s blessings. He remains a practicing, full-time PA at the state pen.

randerson@seattleweekly.com