There’s a new Chinese restaurant downtown. Or at least it looks like a Chinese restaurant, until you get up close and notice the chickens hanging in the window are rubber and the noodles on the tables are plastic. And where the kitchen should be is a sweatshop, complete with young women hunched over sewing machines.

Still, Seattleites come in every week expecting to be fed. “We get a lot of people who want to know when the restaurant is going to open,” says Cal McAllister, who helped design the ersatz eatery. “We bring them in and sit them down and, like a lot of restaurants, just don’t check back with them.”

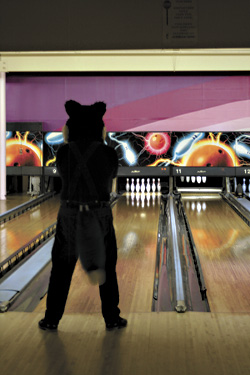

The restaurant is actually part of the new headquarters of ad agency Wexley School for Girls, which moved from Fremont to Fifth Avenue in late summer. The building also holds a camping-themed creative area, where Wexley employees can play nine holes of mini-golf or brainstorm inside a decommissioned RV. Conferences happen in an all-white room featuring plaster busts of Elvis and Beethoven and a table built into a baby grand. On some days, there’s even a pianist in a white cummerbund.

If this pretense seems a bit silly, McAllister knows it. In fact, the 37-year-old U District resident has made silliness a critical component of Wexley’s business plan. “We really kind of want to be ridiculous, and it seems ridiculous that you could actually do business in this building,” says McAllister, whose company does business with Nike, Microsoft, ESPN, and others. “I think overall that Wexley is funny, but it’s not a joke.”

Once upon a time in the advertising industry, it was enough to put out a good product. One of the more memorable campaigns in the Pacific Northwest, produced by Heckler Associates more than a quarter-century ago, featured people dressed as Rainier Beer bottles traipsing through the wilderness. The agency itself stayed out of the limelight, working from offices in anonymous locations such as a Capitol Hill house and a pier near Bell Street that was littered with dead pigeons. “No one knew where we were, ever,” says agency President Terry Heckler.

But modern times don’t guarantee that a good ad will get a good audience. Beyond marketing to a mostly captive crowd of TV, radio, and print viewers, advertisers must pander to a nightmare horde of ADHD-afflicted, TIVO-remote-equipped entertainment whores (to read between the lines of industry journals). The result is that some ad agencies are marketing themselves as entertainment, in the hope that they and their clients will be celebrated as just another freakish manifestation of the zeitgeist.

Wexley is where the kitschy nuttiness of the mid-’90s high-tech workplace (Pac-Man! Beanbag chairs! Super Soaker fights!) meets the high-concept, twee zaniness of the McSweeney’s crowd. Call up the Wexley offices and the voice of a British lady on its phone system offers quaint excuses such as “he’s currently away hunting pheasant.” Wexley’s Web site looks like a gag shop exploded, with bananas, rubber ducks, and pirate ships floating everywhere. (A “not funny” button— which you can’t click fast enough—links to a less-animated site.) On Nov. 15, the 21-employee agency celebrated Wexley Day with a neighborhood parade featuring horse costumes and a red wagon with an inflatable shark in it. Shouted one perplexed onlooker: “We need to know what the parade’s about!”

Or maybe not, according to McAllister. Writing copy for the well-established Publicis agency, he recalls, he grew tired of standard advertising approaches such as a newspaper ad or TV short. He says he lobbied for more event-based, guerrilla-type marketing, and was not well-received. “I’m creating a whole lot of work for them to figure out how in the world they should build an ostrich race because fucked-up Cal over here thinks an ostrich race would be funny,” he says. “There was really no model in how to monetize a weird [idea], like, ‘I wanna do a hot-air balloon with flames coming out of it.'”

So in 2003, McAllister joined up with Ian Cohen, formerly of Portland’s legendary Wieden & Kennedy agency, to create a company that could put on the flightless-bird equivalent of NASCAR, if it so desired. (A third founder has since left.) “The name,” jokes the 40-year-old Cohen, “came from a group of nuns in Wexleyshire, England. They were cantaloupe farmers with a holistic approach to their garden.” Advertising Age put Wexley first on its 2006 list of favorite agency names; the company beat out Tokyo Plastic, 86 the Onions, and Acne.

Of course, Wexley can’t be quite so oblique with its clients. It tries, though: In 2005, the company tapped Jared Hess of Napoleon Dynamite to direct a short film for Nike about two Steves competing to keep the name. The film, in which the losing Steve gets renamed Dingle, appeared in film fests throughout the country. For a Web-marketing company, Wexley helped design an online game that lets players beat up bosses with staplers, water-cooler drums, and overhead projectors.

Wexley is also handling Microsoft’s college-recruitment campaign this school year, using, among other things, a pimped-out cart to transport students around campus and a hot tub in which an actor entertains employment-related questions. That’s meant to show that Microsoft is as cool as competitors Google and Facebook “and all the seemingly younger companies out there and they’re trying to have fun, too,” says Cohen. “So far, the student reaction has been super positive,” avers Margie Medd, the software company’s director of staffing marketing (yes, that’s her title).

And then there’s the stuff, like the parade, that Wexley does on its own time, such as posting a YouTube video of a guy on a forest trail riding a stationary bike and exclaiming, “Ride to live, live to ride!” Cohen’s explanation of such things: “We just like to create our own fun here. Keep the energy up. Keep our creative juices flowing, so when there’s a project, it’s already flowing.”

What sort of “project” are they longing for? Perhaps relaunching a mundane product like hemorrhoid cream. “We might color it like Zinka,” says McAllister. “Remember the old stuff that you would put on your nose? So you could wear it around on your face to let everybody know you had hemorrhoids and you were proud. You’d recognize somebody across the street and they’re like, ‘Hey, you got hemorrhoids, too!'”

As with any joke, Wexley’s brand of affected self-promotion runs the risk of growing stale. “It’s going to have limited appeal and sort of limited durability, I think,” says Heckler. He recalls working in an office where bathing trunks and no shirts was standard dress. “That kind of gets thin when you try to sustain that in front of professionals who are expecting you to offer them some meaningful strategies for their marketing plans.”

Heckler now dresses so conservatively that people always ask him if he’s going to the bank.