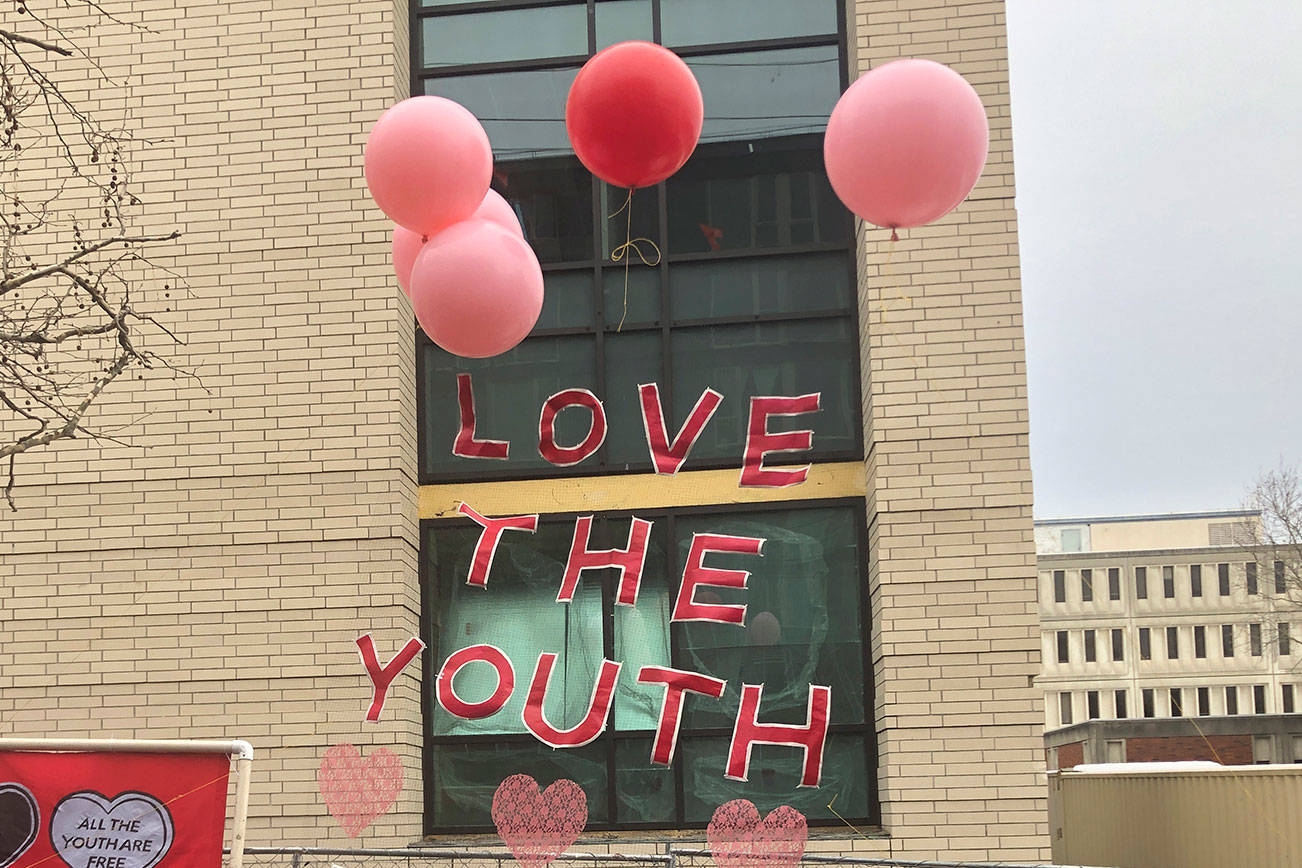

In early March, protesters who opposed the construction of a new juvenile detention center lay down on cardboard in the streets of downtown Seattle for several hours, causing delays on Interstate 5 and Interstate 90.

Seattle Police abstained from arresting the activists who blocked traffic, citing the protesters’ constitutional right to demonstrate. As a result, criminal charges were not filed against the demonstrators at the rally.

“We have a rich history in Seattle of allowing a lot of protests,” Seattle police Deputy Chief Chris Fowler told The Seattle Times in March. “In Seattle, we staff over 300 protests a year, and we have a policy of allowing individuals to express their constitutionally protected First Amendment right on the streets.”

Some of the opponents to the juvenile detention center also resisted arrest by using a maneuver dubbed the “sleeping dragon,” in which demonstrators chain themselves together by inserting their arms into PVC tubing. But the days of protesters creating traffic blockages without facing prosecution could grind to a halt, following City Attorney Pete Holmes’ Aug. 29 Seattle Times op-ed announcing that it’s “likely my office will file charges” against such demonstrators in the future.

At a City Hall press conference Sept. 4, his message drew the ire of environmental, immigrant, and civil-rights activists who called on the city attorney to redirect his attention to prosecuting the fossil-fuel industry instead of nonviolent protesters.

“The Seattle Chapter of the National Lawyers Guild asks why Mr. Holmes is wasting precious resources and why is he clogging up our courts by prosecuting those who seek a better world, but don’t actually harm anyone?” Neil Fox, secretary of the National Lawyers Guild Seattle, said at the press conference.

Fox held a print-out of an iconic photo depicting a student activist who blocked a tank during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. He drew a parallel between the Seattle protesters facing prosecution and the student activists who obstructed military vehicles in Beijing, China. “Would Mr. Holmes prosecute that person? Would he side with the tank driver and say that the student blocking the tank was inconveniencing traffic?” Fox said, urging Holmes to dismiss the current charges against Seattle protesters.

Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant also weighed in by releasing a statement in support of the demonstrators. “The needs of big businesses are meticulously attended to in our city, while working and poor people’s basic need for housing, mass public transportation, and essential services have largely been ignored,” Sawant said. “The fact is protesters are not the cause of our city’s traffic problems, nor do they pose a grave threat to our city’s emergency services. For a city attorney to imply that they are, and to send the chilling message that protesters will be arrested and prosecuted, is unacceptable.”

Although the policy of prosecuting people who intentionally obstruct traffic isn’t new, the tougher stance against activists follows the uptick in unpermitted protests and the resulting arrests of multiple demonstrators who have caused gridlocks in the past few months. In August, Holmes pressed criminal charges against 15 activists who blocked a downtown street to protest JPMorgan Chase’s investment in an oil pipeline and tar-sands development in May.

Alec Connon, an organizer of the climate-justice group 350 Seattle, said that he helped lead the demonstration against JPMorgan Chase in May after the company expanded its funding in fossil-fuel extraction. “We don’t participate in these protests to inconvenience people. We don’t participate in these protests for the sake of being disruptive,” Connon said at the Sept. 4 conference. “We participate in these protests because we recognize the inconvenience of climate change, the inconvenience of having families torn apart are infinitely greater than the inconvenience of being stopped in traffic for a few minutes.”

In his op-ed, Holmes recognized the demonstrators’ liberty to protest, but warned that they should be prepared to face the consequences. His office couldn’t “turn a blind eye” to demonstrators who shut down public roads, Holmes wrote. “They are creating a disruption that redirects vital resources that could be needed elsewhere. While tied up, those firefighters weren’t helping people in crisis and those police officers weren’t walking their beats, preventing crime, or responding to other calls.”

Holmes’ confirmation of his stance follows the Seattle Police Department (SPD)’s new approach to addressing protesters who block traffic. “The difference from earlier in the year to the current practice is that once we have these very unique set of circumstances … where there is an unplanned, unpermitted event that does include blocking arterial traffic, we’ll respond, we’ll evaluate, we’ll communicate, and try to get a better understanding of what the game plan is,” SPD spokesperson Sgt. Sean Whitcomb told Seattle Weekly. Demonstrations like the one in March, in which protesters blocked traffic to oppose the new juvenile detention center, helped SPD recognize when protesters would rather face arrest than stop obstructing roadways, he said: “We arrive to that conclusion faster.”

SPD employed its new practices during its Sept. 3 arrest of 21 hotel workers who demanded better wages by demonstrating outside the Westin Seattle, which is owned by Marriott International. The Marriott workers joined the ranks of more than 100 people arrested at similar protests held throughout the country that day, according to UNITE HERE Local 8 — a union that represents hospitality workers in Washington and Oregon.

“We made a point of working with the organizer and asking them to move, and basically letting them know that if they didn’t move, there would be arrests,” Whitcomb said about the Sept. 3 demonstration. “It was pretty clear that they wanted to be arrested for their cause, which is uncommon, but it’s not unheard of. And so that’s what happened.”

Whitcomb noted that the changes in the department’s practices resulted from “self-reflection and evaluation” after the March demonstration. “Our practices are the result of our own adjustment and recognition that we’re always looking for a better way to support the First Amendment, and the city attorney’s op-ed is separate from our own crowd management,” he said. Whitcomb said he was unaware of the number of protesters apprehended this year, or if there has been an uptick in arrests.

Despite the threat of prosecution, speakers at the Sept. 4 press conference showed no signs of ending tactics designed to raise public awareness. “At this moment in history, we’ve never needed activism more,” Connon said. “When City Attorney Holmes takes a stand against nonviolent protesters trying to stand up against injustice, he is aligning himself with the status quo that is upholding that injustice.”

Holmes wrote in a statement emailed to Seattle Weekly, however, that his office takes threats to the environment seriously: “As I informed the Mayor and City Council in May, my office is in the midst of researching the fossil-fuel industry’s climate impact on Seattle to inform potential forthcoming litigation. We’re working with the Keller Rohrback law firm on this effort, and they’re operating on a contingency fee basis (they don’t get paid unless we secure settlement or victory in the courtroom). If/when the time comes that we have a viable legal strategy to move forward, you can expect that I’ll be submitting an op-ed that highlights the very real threat climate change poses to our planet.”

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com

Sep. 11 update: The story has been amended to include a statement from the City Attorney’s office. It also provides clarification on the increase in unpermitted protests.