Let’s be honest. Voters in Snohomish and Pierce counties are important to the fate of Sound Transit 3. But it will be those living in King County, specifically the city of Seattle, who will determine the outcome Nov. 8.

ST3 will pass, or fail, with a simple majority of votes among those cast in the areas of the three counties served by the regional agency. Yet, since roughly 60 percent of transit district voters reside in Seattle and King County, it is their decision on the $54 billion proposal that will hold the most sway.

Historically, in Washington, voters living in larger cities and urban areas tend to be politically and fiscally more progressive and their turnout soars in presidential years like this one. It proved a winning formula for Sound Transit in 1996 and 2008. Backers of ST3 are counting on it working again in 2016.

Still, ST3 isn’t like its predecessors. It adds more miles of track and builds more stations. It also costs more money and requires more taxes. Supporters are working to convince voters of the worthiness of easing congestion at this price and in this manner while opponents counter that those dollars will not deliver the promised benefits.

It’s a completely different campaign than Sound Transit’s prior efforts.

“If in 2008 we were selling the vision, in 2016 we’re selling the reality,” said Christian Sinderman, the Seattle political consultant who managed the ST2 campaign and is in the same role for ST3.

Eight years ago people could see some elevated tracks and construction, but light-rail service had not begun. Since then stations have opened from the airport to the University District in Seattle.

“Then it was much more aspirational,” Sinderman added. “Now we can say we’ve got rail, trains are running, there are more stations on the way so let’s keep the momentum going.”

It’s an easy sell in Seattle, so long as the many Millennial and Generation X riders remember there’s more on the ballot than just the race for president. Sound Transit is utilizing a variety of means, including social media, to make sure those voters don’t forget to weigh in on Proposition 1, the Sound Transit measure, which will appear near the end of the ballot, Sinderman said.

It’s going to be a harder sell to people in a place such as Everett. Those voters can’t easily discern the benefits of 20 years of taxation, and they now are getting asked to pay even higher taxes knowing it could be another couple decades before they see a light-rail train pull into Everett station.

“The fundamental calculation (for voters) is ‘Is what I’m getting out of this package worth what I am being asked to contribute?’ ” said Rick Desimone, a political consultant and former aide to U.S. Sen. Patty Murray who worked on the 2008 transit campaign, but is not involved in this year’s ballot measure.

“How you win is making sure the different constituencies in each service area feel like they’re getting something for their money,” he said.

With Sound Transit 3 that begins in Seattle. With success hinging on an overwhelming yes vote in the urban center, adding service to Ballard and West Seattle is intended to shore up votes.

And agreeing to a route that takes trains through the Paine Field industrial area in Everett, and near the Boeing Co. plant, is aimed at bolstering support in Snohomish County, where the agency so far has not spent as much money as it has soaked up in taxes.

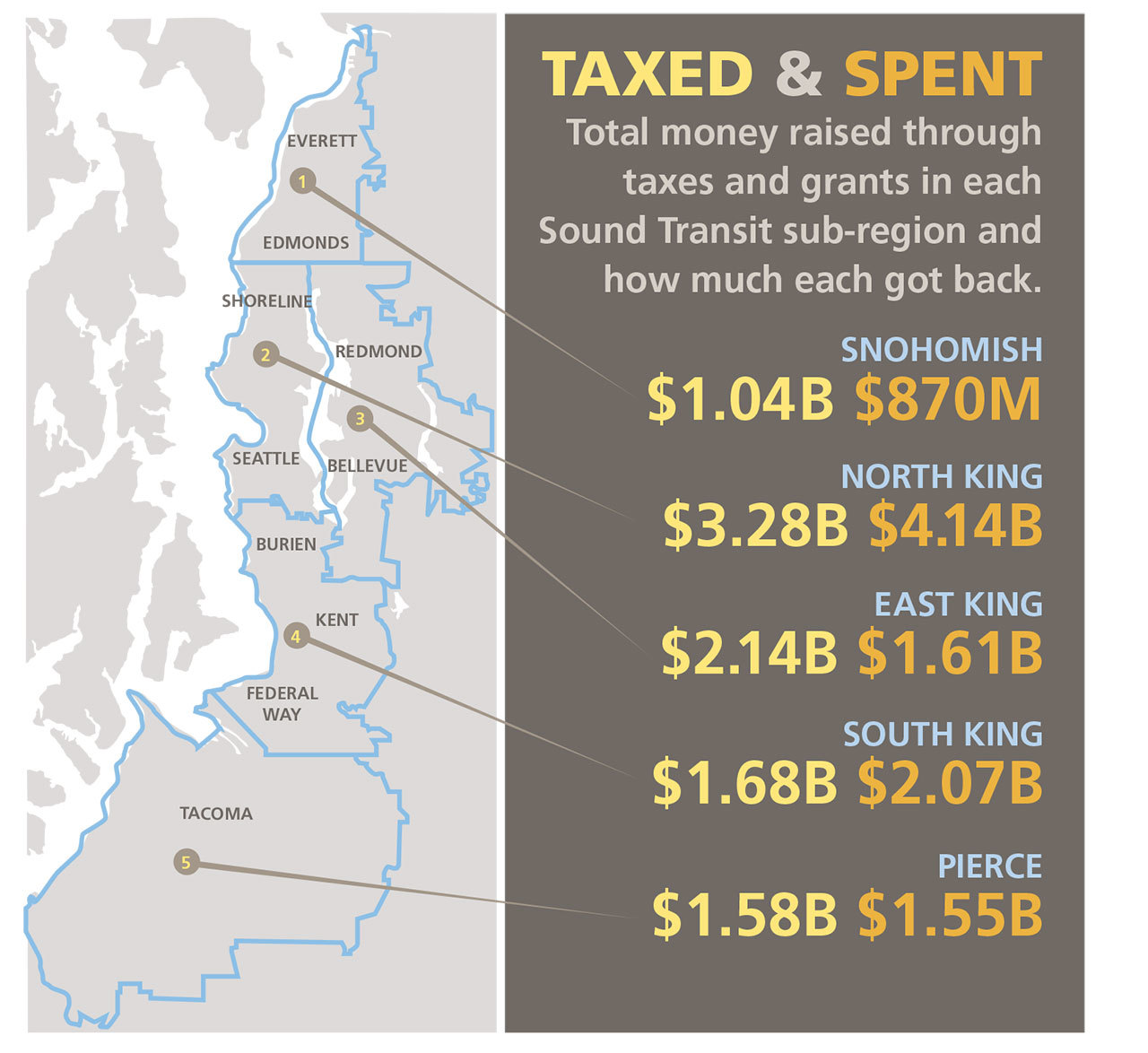

From 1995 to 2015, the regional transit agency took in nearly $1 billion from the Snohomish County portion of the transit district while reinvesting only $870 million, according to agency figures. That’s the lowest sum of investment in any of Sound Transit’s five sub-areas.

East King County, which includes Bellevue, is the only other sub area with an imbalance. It generated $1.9 billion in taxes during the 20-year period while receiving $1.6 billion in projects and service, according to Sound Transit figures.

ST3 will reset the balance sheet, Sinderman said. The campaign must make Snohomish County voters know “there’s a lot in it” for the community, including light rail and expanded bus rapid transit.

This will be the fifth time the question of financing Sound Transit projects will appear on ballots. Thus far the regional transit agency is batting .500 with voters.

They rejected Sound Move in 1995, then approved a retooled version in 1996, coincidentally a presidential election year.

In 2007, voters in all three counties turned down the Roads and Transit proposal. The following year — again a presidential year — Sound Transit 2 reached the ballot and passed, in the process revealing the imbalance of political power.

Pierce County voters rejected the measure by a slim margin. But it won with a large majority (60.5 percent) in King County and a comfortable one (54.2 percent) in Snohomish County.

One could clearly see the influence wielded by King County in the final tally.

Of the nearly 1.2 million votes cast on ST2, 63 percent came from precincts in King County. Pierce County accounted for 22 percent and Snohomish County 15 percent.

Drilling down further, the measure passed by roughly 155,000 votes in King County alone. For perspective, in Snohomish County, the total number of votes cast on ST3 that year — for and against combined — was 174,767.

Opponents of ST3 are conducting a bare-bones campaign fueled with confidence.

No Sound Transit 3 had raised only $10,636 by the end of September, while Mass Transit Now, the ST3 campaign operation, had amassed $2.4 million.

A lack of money means those fighting the measure must be nimble and tireless, said Maggie Fimia of Edmonds, a founder of Smarter Transit and leader of the opposition. She also is a former member of the King County Council.

“The strategy is and has been to get the truth out to as many people as possible as soon as possible,” she said. “We won’t have anywhere near $3 million. We have to have a scaled down, targeted strategic plan.”

They are putting up yard signs, talking with friends and being “present and accounted for” at City Council meetings when resolutions of support or opposition for ST3 are on the agenda, she said.

The opposition’s message is that ST3 will not ease congestion as claimed and may be passé when completed, supplanted by a “transportation revolution” that will be steering travelers to rideshare and automated cars, not light rail.

And Puget Sound residents like their buses. The region enjoys one of the highest bus rider per capita rates in the nation, she said.

“We need more transit now,” she said. “Rail is not a magic bullet for a region like ours.”

Tim Eyman of Mukilteo, promoter of anti-tax initiatives, also opposes ST3 and is a co-author of dissenting statements in the voter’s pamphlet in all three counties.

Fimia isn’t happy about that. Eyman is disliked in many areas of King County, and she said his involvement in the opposition could be enough to get some voters to back ST3 when they might not otherwise.

While Eyman stirs up strong feelings among King County voters, he does have a knack for getting them to reject new and higher taxes. And if there’s one issue Sinderman and supporters don’t want to dwell on too long, it is taxation. Doing so tends to make voters think hard about the potential impact on their wallets.

Paul Berendt, an Olympia-based political strategist and former chairman of the state Democratic Party, said the strong economy in the three counties should help.

“The stress of the pocketbook issues is less pronounced when your income is rising,” he said. “There’s so much need and so much growth going on that people will support anything that reduces their commute times.”

Eyman and former Snohomish County councilman Gary Nelson focused on the cost issue in their voter’s pamphlet statement in Snohomish County.

“Just say No to new property taxes. Just say No to 55 percent increase in sales taxes. Just say No to tripling car tab taxes,” they wrote. “Nothing requires them to deliver what’s promised — projects, costs, and timelines are not binding. Only thing certain are its massive permanent tax increases.”

In an interview in late September, Eyman didn’t forecast ST3’s defeat, noting that having it on the ballot in a presidential year is by design.

“I’ve always had this thought that it is going to be a wave. Voters either repudiate by a huge margin or there is going to be this massive wave of support in Seattle,” he said.

“Sound Transit picked a presidential year for that reason. They wanted the crazies in Seattle to turn out.”