Desperate times call for desperate measures. With an imminent freeze threatening to ruin Washington’s precious apple crop and a severe shortage of migrant laborers in parts of the state, Governor Christine Gregoire and Department of Corrections officials worked out a deal that sent 105 state prison inmates to Grant County to pick fruit. In other words, illegal immigrants are being replaced by illegals of another stripe.

The inmates hail from the Olympic Corrections Center, a minimum-security work camp located near Forks. They will each cost their new boss $22 per hour, and pocket about $2 per hour themselves. The state takes a cut for the cost of transportation, housing, and guards, and also withholds income to pay any overdue child support, cost of incarceration, and victim compensation. Taxpayers don’t foot any part of the bill.

A combination of forces caused the labor shortage, chief among them Mother Nature. A cool spring pushed back picking season several weeks. Many migrant workers simply chose to stay in sunny California, while those here legally on guest-worker visas were sent home early because their employers didn’t anticipate the delayed harvest when they began filling out the necessary paperwork months ago. But migration to the United States by Latin Americans—whom our country has come to rely on for backbreaking but essential labor—is also down this year. Crossing the border is more dangerous because of warring Mexican drug cartels, and states nationwide have enacted draconian immigration laws that have either frightened would-be workers away or forced Uncle Sam to buy them one-way plane tickets home.

Washington isn’t the only state to resort to prisoner pickers. The same thing has happened in Arizona, Georgia, Alabama, and Idaho, where convicts are harvesting the state’s signature spuds for the first time in history. And inmate labor itself isn’t anything new: According to Correctional Industries, which administers Washington’s prison-labor program, “The idea of putting offenders to work in Washington is as old as the first territorial penitentiary built in Walla Walla in 1886.” Thankfully, conditions have improved over the past century.

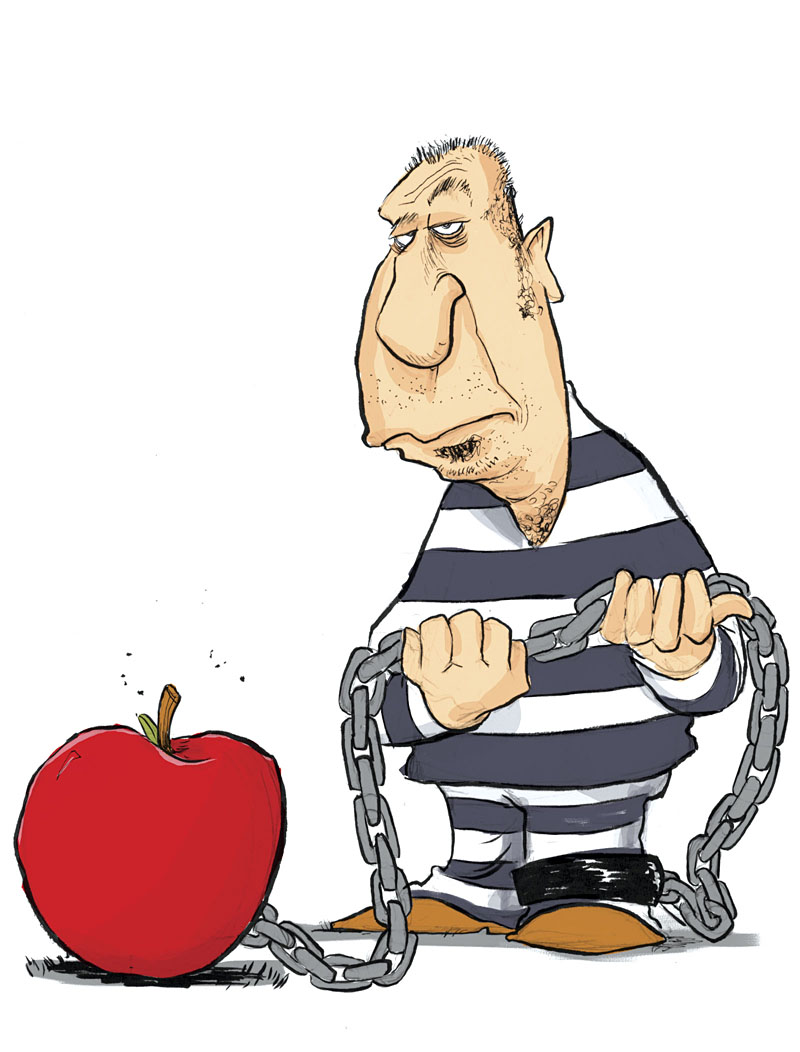

“It’s all voluntary,” assures Mike Gempler, executive director of the Washington Growers League. “I’ve heard people say ‘It’s like the South in the ’50s’—no, they get paid. There are no chains around their ankles. I don’t think there are guys with aviator sunglasses standing there watching them.”

Perhaps the presence of a shotgun or two would induce the prisoners to pick up the pace. Danielle Wiles, assistant director of Correctional Industries, told The Seattle Times that just over halfway into a shift last week, many of the jailbirds had filled only one bin of apples—about one-tenth of what orchard owners have come to expect from their regular workers.

The result is that McDougall & Sons, an orchard in Grant County, is paying a premium to get its crop to market. Even if the inmates improve and start picking three bins of apples per day, the cost is about $58 per bin, roughly four times as much as usual. Nevertheless, the governor, perhaps with no choice but to put a happy spin on the situation, touted the inmate idea as “an innovative solution to this unprecedented challenge.”

“With one in three jobs in Washington state connected to trade,” Gregoire said in an official statement, “we can’t afford to let these apples stay on the tree.”

But with the labor shortage estimated to be as high as 10,000 workers, 105 convicts probably won’t even be able to stock a grocery-store produce aisle for a month. Truly innovative solutions would be to stop enacting laws that persecute migrant laborers and to start overhauling the cripplingly bureaucratic guest-worker program. Gempler recalls that when the inmate-labor idea was first pitched at a meeting last month, he joked that the governor ought to send all state employees to the orchards instead. That drew a laugh, he says, and a week later he headed to Washington, D.C., to lobby for immigration reform on behalf of the state’s fruit industry.

“I’m really happy they take this seriously and respond,” Gempler says of the prisoners-turned-pickers. “It’s just not a total answer.”