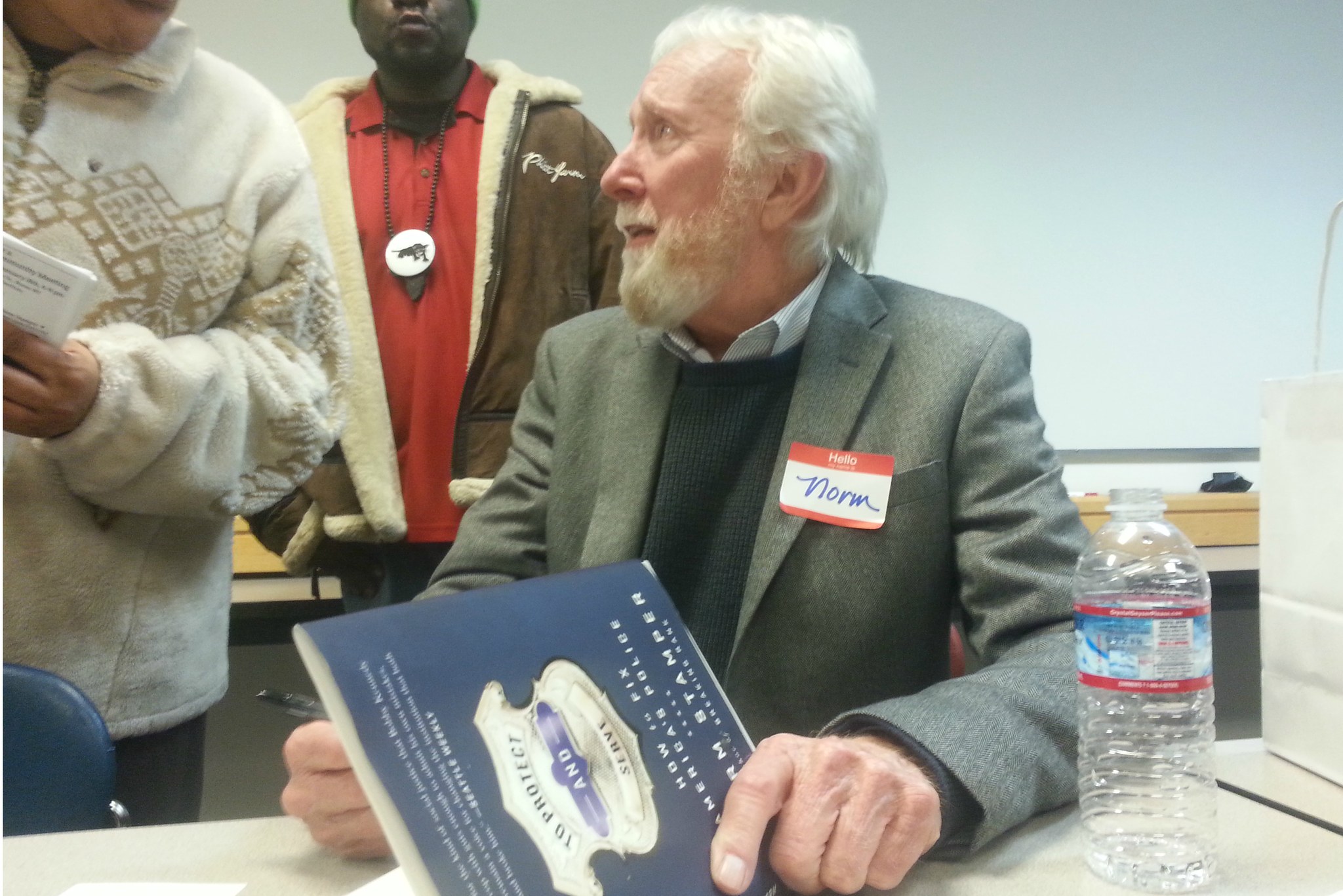

“Police officers are used to exercising authority. They’re used to being in charge,” said retired Seattle police chief Norm Stamper. “Embedded in the culture of policing [are] certain realities, and one of them is, ‘I can’t lose a fight. I can’t run away from conflict…I’ve been hired, in effect, to take charge of this situation.’”

Stamper was speaking to dozens of people inside Seattle Vocational Institute last week. King County prosecutor Dan Satterberg, also present, echoed Stamper’s assessment. “In traditional training, officers would come into a situation, they wouldn’t know any of the parties, and the would begin to give orders. And if [the parties] didn’t follow their orders, they had to give more orders and continue escalating force until their orders were followed.”

The occassion was the weekly meeting of Not This Time, an advocacy group led by Andre Taylor, whose brother Che was fatally shot and left to bleed by Seattle police last year. Their main goal? Changing the state law that shields police officers from prosecution for bad killings. That law originated in 1986, one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that police may no longer shoot fleeing felons simply to keep them from escaping. In response, the Washington legislature amended state law so that police officers who kill people are only criminally liable if a prosecutor can show they killed with “malice” and without “good faith.” In effect, the law says that a police killing is justified if the slaying officer feels that it is justified.

Naturally, no officer has ever been successfully prosecuted under this law. But the law may change. Earlier this month, state Sen. David Frockt of North Seattle introduced a bill that would replace “malice” and “good faith” with objective criteria for whether a reasonable cop would have pulled the trigger in a given situation. From the bill, SB 5073:

“A public officer or peace officer shall not be held criminally liable for using deadly force if a reasonable officer would have believed that the use of deadly force was necessary in light of all the facts and circumstances known to the officer at the time.”

Frockt’s cosponsors are senators John McCoy, Jamie Pedersen, Bob Hasegawa, Jeannie Darneille, Maralyn Chase, Sam Hunt, and Lisa Wellman. Rep. Cindy Ryu just sponsored a companion bill in the House of Representatives, joined by Sharon Santos, Laurie Jinkins, Steve Kirby, Gerry Pollet, Tana Senn and Laurie Dolan.

The bills’ language is taken verbatim from last year’s Joint Legislative Task Force on the Use of Deadly Force in Community Policing, of which Frockt was a member. Not This Time supports the bill, as does Washington for Good Policing, a group that has partnered with Not This Time in the past. “We’re working the legislature with everything we’ve got,” says W4GP’s Lisa Hayes, to support Frockt’s bill, including hiring a lobbyist. Frockt’s bill is not the only one: HB 1000 and SB 5000, which are companion bills, would also remove “malice” and “good faith” but would also add much stronger language regulating the circumstances in which police may kill people, going so far as to prohibit police from shooting “at or from a moving vehicle unless deadly force is being used against the officer or another person present, by means other than a moving vehicle.”

“We support all the recommendations” in the task force report, says Gabe Meyer, advocacy director with Not This Time, “but we also believe that the malice and good faith intent clause are the most important pieces of the recommendations. If there’s a bill that ends up watering down that part…we don’t consider that a victory.

“A victory is only changing those two parts of the law.”

If the legislature doesn’t remove the “malice” and “good faith” requirements, Not This Time is determined to do it for them via initiative on the November 2018 ballot. To do so, they would need to gather just under 250,000 valid signatures, equal to eight percent of the number of voters in the last gubernatorial election. Meyer says the campaign hasn’t yet decided whether that would be an initiative to the legislature or to the people. The former allows signature gathering through the end of the year, says Meyer, which can be enough time for volunteer-driven organizations. The latter is shorter and therefore typically requires paid signature gatherers, he says. Both kinds go to the November ballot—unless, in the case of initiatives to the legislature, legislators vote to pass it ahead of time.

In the meantime, Not This Time is “building power,” says Meyer. “We are setting the foundation” for a November 2018 initiative, while hopefully watching the current legislative session unfold.