In 2007, having served with distinction during two deployments to Iraq and one to Afghanistan, U.S. Air Force firefighter John Brownfield Jr. took a job as a correctional officer at the maximum-security federal prison in Florence, Colo., 40 miles south of Colorado Springs. Ten months later, prison officials caught the ex-senior airman smuggling tobacco to at least seven inmates at the facility and accepting at least $3,500 in payoffs. The U.S. attorney for the District of Colorado charged the 22-year-old combat veteran with bribery by a public official. Brownfield pleaded guilty.

Two years later, Sgt. Dreux Perkins returned home from a combat stint in Baghdad—his second overseas tour of duty with the U.S. Army—received his honorable discharge, and went to work as a correctional officer at the medium-security Federal Correctional Institution in Greenville, Ill., 50 miles east of St. Louis on Interstate 70. This past May, the Federal Bureau of Investigation confronted Perkins with evidence that he’d accepted at least $2,600 in payoffs for smuggling cigarettes into the prison. The U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Illinois indicted the 23-year-old decorated war veteran for bribery by a federal official, two counts of wire fraud, and two counts of making a false statement to a federal law officer. Perkins pleaded guilty.

The two soldiers have never met, but the similarities between them go deeper than their parallel career-to-crime trajectories.

Though he had not been formally diagnosed, Brownfield manifested symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. A presentencing report in the former soldier’s case noted “incidents of his alcohol abuse, excessive sexual activity, fighting in bars, and domestic violence.”

Perkins was diagnosed with PTSD after he sought counseling at the VA St. Louis Healthcare System. A psychologist there diagnosed him with the disorder, but Perkins was already in a downward spiral he could not control, gambling the nights away at St. Louis-area casinos and, as his losses mounted to the point where he couldn’t pay the mortgage on the home he’d bought, smuggling cigarettes into the prison in return for cash.

In the federal court system, the fates of the two young soldiers diverged.

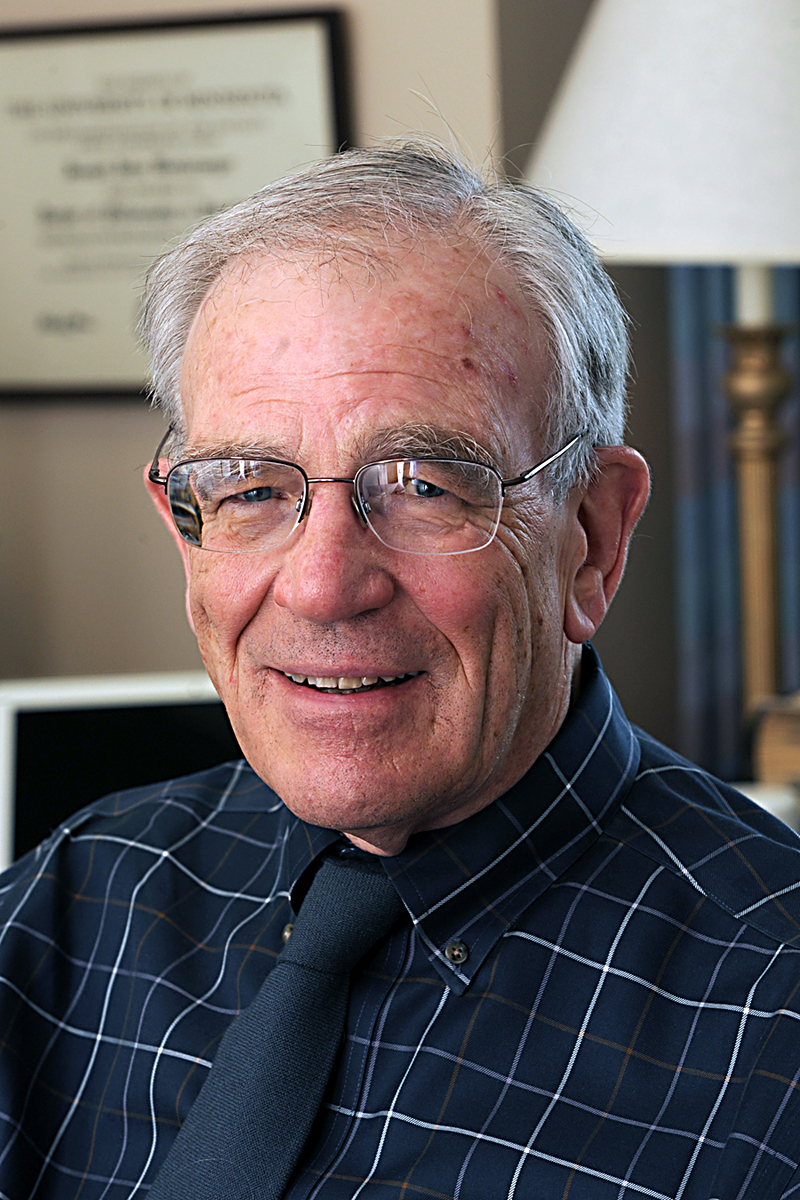

Prior to sentencing, Brownfield’s attorney asked Senior U.S. District Judge John L. Kane to take into account his client’s military service and his PTSD-like symptoms. The federal prosecutor handling the case sought a prison term of one year and one day. Kane ignored the sentencing guidelines and sentenced Brownfield to five years’ probation.

“Figuratively speaking, Brownfield returned from the war, but never really came home,” Kane wrote in a detailed 30-page sentencing memorandum, adding: “We are now, in a manner of speaking, charting unknown waters.”

Perkins’ lawyer also asked for leniency, citing his client’s PTSD, his pathological gambling addiction, and a letter from his psychologist recommending treatment in a VA-operated residential program.

U.S. District Judge Michael J. Reagan sentenced Perkins to two and a half years in federal prison.

While officials in federal courts have gained an increased understanding of combat-related PTSD in recent years, a seemingly related mental illness—pathological gambling—remains largely overlooked, despite a growing body of scientific research suggesting that gambling addictions are alarmingly common among servicemen returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan. For afflicted servicemen who commit crimes post-deployment, the prospect of getting paired with a sympathetic judge amounts to a roll of the dice.

“Gambling, just like drugs, allows you to keep distress, depression, and anxiety at bay and remain in control of your own mind,” says Minneapolis VA Health Care System staff psychiatrist Dr. Joseph J. Westermeyer, a professor at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “So for veterans who are distraught—maybe thinking they’re a coward because they lived and their comrades died—they sometimes think gambling can save them.”

In 2011 Westermeyer, who has studied addiction for 40 years and served for a time as the Minneapolis VA’s director of mental-health services, completed a VA-funded study that delivered a jolt to his profession. He looked at the gambling behaviors of 2,185 vets who had sought treatment at least once in the prior two years, either at the Minneapolis VA or at the New Mexico VA Health Care System. He found that 2 percent had a pathological gambling addiction and another 8 percent had a gambling problem—double the rates commonly found in surveys of civilian populations.

The data portend a greater problem in the future, judging by the shockingly high number of younger veterans who exhibited so-called problem gambling—often a precursor to (and thus a major predictor of) pathological gambling.

On February 8, with a week of freedom between him and the scheduled onset of his prison term, Perkins nurses a Bud Light at a sparsely populated sports-themed restaurant just off I-70 in Troy, Ill,. At 26 he has the look of a broken man. His voice is soft and gravelly, his gaze distant. He’s wearing a fishing-shop T-shirt that smells like the cigarette he just smoked outside. The 180-pound soldier who manned an armored personnel vehicle in Iraq is now a saggy-gutted convict-to-be, having packed on 45 new ones.

It gets worse: A day ago Perkins and his girlfriend learned that the baby she is carrying has no heartbeat. Tomorrow she is scheduled to deliver the couple’s stillborn fetus, five months after conception.

If Dreux Perkins’ life were a movie, right about now the restaurant’s sound system would cue up John Mellencamp’s “Pink Houses.” It’s not, but it does anyway: “Ain’t that America?”

His myriad trips to the casino, Perkins allows, were “basically an escape—a way to take my mind off everything”; his decision to smuggle in cigarettes to an inmate, stupid. “I knew what I was doing was wrong,” he says. “But gambling superseded the consequences.”

Dreux Perkins (his first name is pronounced drew) graduated in Greenville (Ill.) High School’s class of ’04, an all-conference linebacker who led the Comets football squad in tackles in his senior year. In his spare time, the happy-go-lucky teenager rode motorcycles and snowboards and hunted with his dad, a retired first sergeant for the army.

A year out of Greenville High, motivated by the September 11 terror attacks and ongoing wars in the Middle East, Perkins followed in his father’s military footsteps. His first assignment sent him to Korea as a radio operator. By the time he was reassigned a year later, he had 10 soldiers under him and spent his spare time as a volunteer teaching English to Korean children.

But Perkins had enlisted to fight a war, and he lobbied successfully for a transfer to Fort Campbell, Ky., where the 101st Airborne Division—the venerated “Screaming Eagles”—was preparing for deployment to Baghdad. Training included overseeing “prisoners” at a mock Iraqi jail, where he and his comrades were taught to be firm, fair, and consistent.

After the unit landed in Baghdad in April 2008, Perkins assumed a communications role. When the young soldier made it clear that he wanted to be closer to the action, his leaders moved him to a VIP security detail, where he chauffeured top brass and other emissaries into and out of the Green Zone. His 13-man platoon managed a quartet of Mine Resistant Ambush Protected tanks, 40,000 pounds of bulletproof steel apiece. “Pretty soon [the tank] getting shot was, like, whatever,” Perkins says with a shrug.

“Dreux Perkins was one of my finest junior NCOs. He served daily in some of the most dangerous neighborhoods of Baghdad,” attests Capt. Josh Lyons, at the time a second lieutenant who led the platoon. He says he and Perkins occupied the same personnel carrier for about six months, during which they made 151 trips along the Baghdad Airport Road, better known as Route Irish. “Dreux was a great soldier with unlimited potential in the enlisted ranks.”

When he said he could handle more, Lyons moved him from driver to gunner. Perkins directed his tank from its turret, where he was able to swivel 360 degrees and fire at insurgents on sniper towers and bridges. Documents from his case indicate that he performed above and beyond. Several months into Perkins’ Baghdad tour, the army promoted him to E-5 sergeant. He’d already received several commendation and achievement medals. While on leave over Christmas in 2008, he returned to Greenville and proposed to his then-girlfriend, Kelly Derrick.

But under the surface, Perkins was struggling. He’d absorbed painful shocks from roadside bombs; medical records indicate that on at least two occasions, IEDs (improvised explosive devices) knocked him unconscious. He took the lives of several attackers, and others returned the favor, killing a handful of his buddies over the course of his deployment. Going on four years later, he says he’s still haunted by images of flesh-splattered tanks rolling home to the base.

In Baghdad he found it increasingly difficult to transition from battlefield action, during which there was no time to think, to downtime at his housing unit in Camp Liberty, when bouts of boredom led to creeping doubts about the war’s purpose.

There was, however, an antidote to the monotony: poker.

Perkins, who says he’d never gambled before, recalls anteing up for his first hand of Texas hold ’em. What began as a once-a-week diversion escalated to a nightly routine, fueled by the buzz of energy drinks combined with wagering limits that ballooned to $200 a round. Every now and then, a fellow player’s wife would ship over a care package with whiskey disguised as Mott’s apple juice.

The U.S. Central Command had banned all forms of gambling in Iraq, and fraternizing with subordinates violates the government’s Uniform Code of Military Justice; Perkins knew full well he was breaking the rules, but as long as they kept it to themselves, no one cared. “All that garrison crap goes out the window once you’re in Iraq,” he explains. When they sat down to play, he’d tell the soldiers around the table not to call him Sergeant.

Every now and then, the level playing field at the card table bled onto the battlefield, and Perkins would find his authority questioned by a subordinate. But mostly poker provided a much-needed respite from the war’s psychological toll. Gambling with their money at night seemed a fair trade-off for gambling with their lives by day.

“It was almost like a high,” says Perkins. “That’s all we looked forward to. Even out on missions, it was all we talked about—how we were going to play cards that night. It got to the point where sometimes we’d start at six and we wouldn’t be done until three in the morning.”

Heather A. Chapman, deputy director of the Veterans Addiction Recovery Center at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, doesn’t have enough room to treat all the veterans who seek refuge in her gambling treatment program. “I could easily, without blinking, double the size of the program—if we had the beds,” she says.

Chapman’s clinic—the only inpatient gambling program within the national VA system—recently moved from nearby Brecksville, Ohio, where it was created in 1972 by the psychiatrist Robert Custer, the man largely responsible for persuading the profession to recognize that pathological gambling is a mental disorder. Custer’s Brecksville clinic wasn’t only the nation’s first gambling treatment program for veterans, it was the first gambling treatment program, period.

Former soldiers still come to Cleveland from all across the U.S. Chapman ticks off a few of the more memorable case studies: the vet who blew $80,000 at a casino in a single day. The vet who gambled away so much in a month that he lost 17 pounds because he had no money to buy food. The vet who put a staple gun to his head after running his finances into the ground—and kept up the losing streak by blowing the suicide attempt.

Chapman’s patients have gambled away nest eggs, discarded friendships, pawned belongings, had cars repossessed, and lost jobs, spouses, and custody of their children. Seventy percent of her clients report having committed crimes to bankroll their binges.

Apart from Chapman’s clinic, only a handful of VA hospitals nationwide operate outpatient gambling-treatment programs. Yet research and anecdotal evidence alike suggest the problem is widespread and growing. In addition to Westermeyer’s study (slated for publication in an upcoming edition of The American Journal on Addictions):

• A 2008 study involving a cohort of 31,000 active-duty airmen showed that 1.9 percent had no control over their gambling and 10.4 percent gambled weekly at minimum. “This rate is concerning,” wrote the authors of the study, which was published in the journal Military Medicine.

• A 2003 VA-funded study of Brecksville patients found that 40 percent had attempted suicide at least once.

• The U.S.VETS (United States Veterans Initiative) Las Vegas Division, a transitional-housing and treatment program, reports that 20 percent of its clients have gambling problems, compared to Nevada’s rate of 6 percent calculated by the Nevada Council on Problem Gambling. “The number is growing,” says U.S.VETS Las Vegas operations manager Jessica Rohac.

Researchers believe two separate factors make veterans disproportionately susceptible to pathological gambling. One is the roller-coaster-like thrill of winning (or losing) when the stakes are high, which mimics the adrenaline rush that occurs in the heat of battle. Gambling provides a nonlethal escape—and why save today when you could die tomorrow?

The second reason involves escape of another sort: For some veterans who return from combat with deeper psychological wounds, gambling functions much like a narcotic. Rather than seek out crowded poker tables, these vets tend to zone out in front of slot machines, whose hypnotic whirls and hallucinatory lights, whoops, and sirens provide a numbing electronic morphine. Chapman estimates that 35 percent to 40 percent of her patients have PTSD; for many, she surmises, slot machines “are like wonder anesthetic.”

Research aside, common sense suggests that gambling and the armed forces are a combustible combination. Those who enlist tend to be risk-takers to begin with. And because military culture has little tolerance for behavioral problems, there’s less motivation to seek counseling. Pathological gambling has long been correlated with elevated rates of trauma, depression, and substance abuse—all of which affect veterans at high rates. (And it’s safe to say the war-movie poker game is a cinematic cliché rivaled only in the jailhouse genre.)

Duane A. Kees, an Arkansas-based military lawyer, says he deals with two or three gambling cases a year. “You see it over and over with combat vets,” he says. “They get caught for stealing or selling military property to support their addiction. They get charged with theft or fraud—but gambling is their underlying rationale.”

Still, some researchers dismiss the oft-cited claim that the overall incidence of pathological gambling in the nation’s adult population as a whole is roughly half the rate found among military vets. “I don’t see anything that would make me sit up and say, ‘Oh my gosh, veterans are ever more so susceptible to developing pathological gambling,’ ” says psychologist Robert Breen, director of Rhode Island Hospital’s Gambling Treatment Program.

“The jury is still out,” echoes Christine Reilly, senior research director for the Washington, D.C.-based National Center for Responsible Gaming, a nonprofit operated by the American Gaming Association, the most powerful and well-funded pro-gambling lobby in the country.

Sometime in the next year or two, the American Psychiatric Association is set to publish the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known as the DSM), the universally accepted compendium of every recognized mental illness in existence. Research teams are considering proposals to redefine autism, depression, and schizophrenia, among other disorders.

One pending matter is the proposed reclassification of pathological gambling from its current habitat, the “Impulse-Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified” category (which includes obsessive maladies such as pyromania and kleptomania). If the reclassification goes through—as gambling researchers expect it will—pathological gambling will become the first behavioral disorder to be classified as an addiction. Its new home in the DSM, currently labeled “Substance-Related Disorders,” will require a rechristening to mark the occasion, to “Addiction and Related Disorders.”

The semantic relocation has a lot riding on it: In terms of the allocation of research and treatment funding, it’s the psychiatric equivalent of moving from the outhouse to the penthouse.

The majority of psychiatrists and psychologists favor the change in light of the scientific literature supporting it. Addiction specialists call slot machines the “crack cocaine” of entertainment, citing studies that compare functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans of the brains of pathological gamblers and cocaine addicts: When study subjects are presented with stimulating cues, the dopamine-carrying neural pathways in both populations’ prefrontal cortexes light up in identical patterns.

In a sense, pathological gambling is the cruelest of all addictions. Gamblers and researchers alike refer to it as “the hidden addiction”: There’s no pee test, and you can’t smell dice (or deuces) on someone’s breath. Says Chapman: “Some vets come to me saying they wish they had a substance addiction because you pass out after too much of it. With gambling you can’t pass out.”

Keith S. Whyte, executive director of the National Council on Problem Gambling, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, has formed a military task force to lobby Congress to earmark money for a federal epidemiological study to grasp the full scope of the problem among veterans. “We think the evidence is pretty clear that gambling addiction is underdiagnosed and undertreated among vets,” says Whyte, who believes every veteran who checks into the VA for a mental-health problem should be screened for gambling addiction. “The VA might say they don’t have many patients who present for gambling problems. But they’re not asking.”

This fall Whyte intends to present to Congress a white paper with the working title “Warriors at Risk: Gambling and Problem Gambling in the Military.” Author Kamini R. Shah conducted the bulk of her research through the Washington University School of Medicine and the St. Louis VA while earning her doctorate from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“The fact males and females showed equal rates is a huge finding,” says Shah, noting that in the U.S. population at large, women who are pathological gamblers are outnumbered by men two to one. “And it’s important that we say to the government: ‘Hey, open your eyes.’ “

When Dreux Perkins returned home, he tried not to think about the war. He began drinking close to a fifth of Jim Beam at night and having nightmares about the killings. He also continued to gamble, playing Texas hold ’em at Lumière Place Casino in downtown St. Louis. He scored big early on, winning $7,800 one evening and $3,900 the next.

Eventually, says Perkins, Lumière lost its allure. So he started hitting the slot machines on the opposite bank of the Mississippi, at the Argosy Casino in Alton, Ill.

Slowly, his demeanor began to change. He lost his sex drive, developed a hot temper, distanced himself from those closest to him, and became verbally abusive to his fiancée.

Derrick, now 26, says the man she pledged her heart to was compassionate, tender, and responsible with money, while the postwar Perkins was inconsiderate and deceitful. “He was a total flip-flop,” says Derrick, recounting the lies about the dwindling bank account and time spent away from home. “He’d say he was going out with friends or helping someone move, but he was going to the casino.”

Says Perkins: “She didn’t know what the hell was going on with me. People told me I was just numb and didn’t really care about anything. Gambling was the only type of enjoyment I was getting.”

They called off the engagement and eventually split for good.

On December 27, 2009, Perkins called a crisis hotline and said he’d been throwing up every day and needed help. The following week he checked into the St. Louis VA’s Jefferson Barracks Division, complaining of nightmares, nausea, and sitting anxiously in corner restaurant booths, watching his back.

Less than a month later, Perkins was back at the VA. “The veteran became highly anxious and tearful when attempting to recount the event(s) and chose to limit his recounting to the sight of dead bodies (particularly close friends and innocent [Iraqis]),” reads a report his psychologist filed. “The veteran reported that he has nightmares about ‘the dead bodies’ approximately ‘every night’ and that he awakens in a highly anxious state with his ‘heart pounding.’ “

During that session, Perkins described an incident in which a rock hit his windshield; mistaking it for a bullet, he momentarily lost control of his car. He said his new girlfriend, Emily Gehrig, told him he screamed in his sleep.

Perkins’ VA psychologist diagnosed him with PTSD. But the sergeant failed to follow up much at the VA that year. Instead, he continued gambling. In a two-month span, Perkins says, he blew through $15,000, maxing out his credit card. Unable to scrape together enough for his monthly car payment, he began selling off personal belongings. He fell into arrears on his mortgage. And while on duty at the federal prison in Greenville, he confided to an inmate the extent of his financial straits.

Khalat Alama, an Iraqi American in his mid-20s from Lincoln, Neb., was serving a 16-year sentence for possession of and conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine. As Perkins relates and federal investigative documents confirm, Alama offered the corrections officer $600 in exchange for smuggling two packs of cigarettes into the prison.

Perkins left the cigarettes in the bathroom adjacent to his office, where Alama could find them during his custodial rounds. Alama’s brother wired Perkins $600—enough to cover his mortgage.

Between mid-2010 and mid-2011, Perkins smuggled in cigarettes several more times, for Alama and two other inmates, he says. He gambled away the proceeds.

At some point, says Perkins, Alama ratted him out to prison officials, accusing him of drug smuggling. The court record contains no reference to Alama’s role as an informant, but a source close to the investigation, who spoke on condition that his name not be revealed, confirms Perkins’ account, including the false allegation regarding illegal drugs. A spokesman for the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Illinois confirms that “a [marijuana-smuggling] allegation was made, but we decided not to pursue it.” Alama did not respond to a written request for comment regarding Perkins’ version of events.

In May 2011, Alama promised Perkins $2,000 in exchange for smuggling a carton of smokes. On the verge of losing his home and car, Perkins took him up on it. This time, rather than working through Alama’s brother, Perkins consented to collect the money and cigarettes from a woman later cited in court documents as “Liz.”

When Perkins entered the Saint Louis Bread Co. on Loughborough Avenue on May 12 of last year, he sensed someone was watching him. “But I just kept thinking about gambling,” he says.

He found Liz sitting at a table. She produced a plastic bag containing a carton of cigarettes, two loose packs, and an envelope containing $2,000 in cash. “You could see right through the bag,” Perkins recalls. “In my head, I’m like, ‘This is a setup.’ But I wasn’t thinking straight.”

Perkins took the money and drove straight to the Argosy. It took him two hours to blow through the entire two grand. Two days later he arrived at work with 60 cigarettes secured inside two zip-lock bags: one in a jacket pocket, the other stuffed down his pants. Two federal agents, who had him under surveillance during his visits to the cafe and casino, pulled him aside.

Sensing a bluff, Perkins denied any knowledge of the smuggling scheme. The agents produced a warrant, searched him, and discovered the contraband. After presenting him with photographs from the Bread Co., the agents asked Perkins where he’d gone after meeting Liz. Perkins said he drove home. The agents produced photos from the Argosy. Faced with evidence he knew to be genuine, Perkins signed a confession on the spot. The agents let him go.

Two days later Perkins called his psychologist in a panic. He checked into the VA’s emergency room, reporting that he was “stressed out drinking and gambling.” He remained in the psychiatric ward for two days. Two weeks later he began to receive gambling counseling, which helped. “It really opened my eyes,” he says now.

In September he pleaded guilty to all federal charges, and the court scheduled his sentencing hearing for January.

Federal prosecutor Steven D. Weinhoeft acknowledged Perkins’ military valor and his PTSD. But as a correctional officer, he argued, the defendant was well aware he was committing a crime. Perkins’ gambling binges were “utterly selfish,” Weinhoeft asserted.

“[Y]ou look at what he’s done,” the assistant U.S. attorney told the judge. “He’s thrown away his career. He has significantly damaged the institution that he worked for. He’s compromised the integrity of the profession that he was involved with.”

Speaking on Perkins’ behalf, defense attorney Daniel F. Goggin zeroed in on his client’s combat-induced transformation. “[Y]ou take these kids in at a young age to send them to battle. You have to break them down and train them to kill people, because you can’t take a normal person who’s lived a normal life and tell them to go kill somebody,” Goggin argued.

When soldiers come home, Goggin went on, “They don’t know how to calm down. They were in that situation thinking ‘I’m going to die any second’ for a couple years. So they just start doing classical behavior. They beat their partners, start drinking, they start gambling. Mr. Perkins’ case was gambling, chronic gambling.”

Goggin closed by noting that if his client were to be sentenced to 30 months—the minimum prescribed by federal guidelines—his veteran’s benefits would expire, making him ineligible for VA counseling upon his release.

Given the chance to speak, Perkins was brief. “I just want to, first and foremost, say—just apologize to my family for putting them through all this. And just really ashamed of myself, my actions for—the person I am today, just completely different from the person I used to be, and I just want to get the help that I need so I can be the person I was. That’s all.”

Before issuing his ruling, Judge Reagan commended Perkins on his military service and acknowledged his PTSD and gambling addiction. But smuggling contraband into prison, be it tobacco or illegal drugs, is serious business, the judge declared.

“Anything that upsets the delicate balance of power between the guards and the inmates or the inmates and other inmates can turn calm into chaos,” Reagan said before sentencing Perkins to 30 months. He chose the low end of the recommended range, the judge explained, in light of Perkins’ military service. He also ordered the defendant to steer clear of casinos for three years after his release.

Alama pleaded guilty to conspiracy to bribe a federal official and bribery of a federal official. Thirty months was tacked onto his prison term.

Before his client was sentenced, Goggin gambled on a legal long shot: He requested that the court reassign Perkins’ case to a so-called veterans treatment court, hoping that Judge Reagan might apply at the federal level a trend that in recent years has gained significant traction at the state level.

Many veterans who suffer from combat-related mental illness land in the legal system as first offenders. The vet-court concept is analogous to drug court, offering defendants a second chance by reducing prison terms or bypassing convictions altogether if the accused agrees to participate in individualized, VA-run treatment programs and check in regularly with the court. The setup is doubly attractive to politicians, in that it provides positive press fodder and saves taxpayers money.

Associate Judge Robert Russell of Buffalo, N.Y., opened the first such court in 2008 after seeing veterans who came through his drug court interact positively with one another. In the three years beginning in 2009, the number of vet courts in the U.S. swelled from four to 92, according to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, a nonprofit agency based in Alexandria, Va.

The movement has been slow to gain a foothold at the federal level, but that tide has begun to turn. “The idea is starting to percolate,” says Magistrate Judge Paul M. Warner of the District of Utah, who instituted the nation’s first federal vet court in 2010. Warner spent six years in the Navy before joining the Army National Guard’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps, retiring as a colonel. He says he relies on district judges to refer appropriate cases to him.

“The defendants respect that I’m an Army colonel a lot more than the fact I’m wearing a black robe,” he says.

The Western District of Virginia recently opened a vet court, and in February of this year, a 45-year-old Persian Gulf Navy veteran, who’d been charged with multiple felonies related to manufacturing a weapon, avoided conviction and a 40-year prison sentence by completing his treatment program.

This past March, a 32-year-old Army vet who developed PTSD after deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan became the first graduate of the Western District of New York’s vet court, which is administered at the state level. The charges against him—assault, threatening to kill a VA worker, and threatening to bomb a Buffalo television station—were dropped.

In the Eastern District of Missouri, U.S. District Judge Stephen N. Limbaugh Jr. quietly opened a federal vet court this past October in Cape Girardeau. (Prior to his appointment to the federal bench in 2008, Limbaugh had served on the Missouri Supreme Court; his cousin, radio raconteur Rush, is somewhat less apt at flying under the radar.)

Coincidentally, the fifth federal-level vet court might take root in the Southern District of Illinois, raising the possibility that Dreux Perkins can add a bad-timing card to his hand of misfortunes. Since opening a vet court in Madison County in 2009, Circuit Judge Charles Romani Jr. has graduated 35 defendants, only one of whom has reoffended. He says he’s willing to take on federal-level cases, and he has found an ally in Madison County Assistant State’s Attorney John Fischer, who plans to pitch the idea to U.S. Attorney Stephen R. Wigginton sometime in the next few months.

“We’re trying to stay ahead of the game,” Fischer says. “This would be a measure to help out these veterans by filling the gap until the government wants to implement vet courts at the federal level.”

Meanwhile, civilian offenders suffering from gambling addictions might soon have their day in diversion court. “With gambling moving over to the addictions in the DSM, I hope they just start calling them addiction courts,” says Jeremiah Weinstock, a Saint Louis University psychology professor who is investigating proposed changes to the pathological gambling criteria for the upcoming DSM.

The U.S. already has one gambling court. Judge Mark Farrell, senior justice for criminal and civil courts in the affluent Buffalo suburb of Amherst, N.Y., set up shop in 2001 after learning that many of his fraud and larceny cases stemmed from gambling addictions. Though he hopes other judges follow his lead, he doubts many legislators will rally to the cause anytime soon.

“The government is facing a budgetary shortfall as is,” notes Farrell, adding that casino taxes are a major source of tax revenue. “This is a subjective opinion on my part, but who’s the biggest partner for gaming? Government.”

Casino taxes aren’t the only source of gambling-related government revenue. Military personnel fork over a hefty chunk of change.

A spokesman for the U.S. Army says its Recreation Machine Program operates 2,189 electronic-gaming machines on overseas Army, Navy, and Marine bases outside combat zones worldwide. A similar program administered by the Air Force accounts for another 1,100 machines.

In the fiscal year ending September 30, 2011, the military netted $142.3 million through its slot machines. The funds are earmarked for the upkeep of golf courses, bowling alleys, skate parks, and other recreational facilities the military operates for personnel and their families.

Slot machines first appeared on bases in the 1930s. In 1951, following passage of the federal Transportation of Gambling Devices Act, the military removed machines from stateside bases. Two decades later, the Army and Air Force banned all machines in response to allegations of corruption and mismanagement; they were reinstituted in 1980.

The Department of Defense has been studying gambling among active-duty service members at least as far back as 1992, when it added the activity to its “Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Military Personnel” (SHRBAMP), a questionnaire distributed and tabulated every four to six years. The 1992, 1998, and 2002 surveys suggested elevated rates of probable pathological gambling among active-duty servicemen.

The DoD took action: Henceforth, gambling questions were omitted from the survey.

In 2001, prompted by Congress, the Pentagon produced a 13-page document titled “Report on the Effect of the Ready Availability of Slot Machines on Members of the Armed Forces, Their Dependents, and Others,” which averred that slot machines had no negative effect on the morale or the financial stability of military personnel or their families. “Comparisons of the [SHRBAMP] survey data to the general public cannot readily be made,” the authors added. (The Pentagon initially contracted with PricewaterhouseCoopers to conduct the study but terminated the contract after a few months, opting to use its own researchers.) The DoD has not released a slot-machine report since then.

In 2005, The New York Times published a front-page article about the military’s gambling operation that described the downfall of Aaron Walsh, a decorated Apache helicopter pilot who became addicted to gambling while stationed in South Korea, where he lost more than $20,000 playing slots. After leaving the military, Walsh wound up homeless in Las Vegas. In 2006 he committed suicide.

Not long afterward, U.S. Rep. Lincoln Davis of Tennessee proposed the “Warrant Officer Aaron Walsh Stop DoD-Sponsored Gambling Act,” calling for a ban on military slot machines. “We’ve got research to show that 30,000 of our troops may be pathological gamblers, and we ought to be ashamed that we’re adding to that,” Davis told Stars and Stripes in 2008. His bill died in committee.

Dreux Michael Perkins and Emily Gehrig buried their stillborn son, Dayne Michael Perkins, on Valentine’s Day. Judge Reagan stayed Perkins’ sentencing one week so he could be at Gehrig’s bedside. On February 22, Perkins drove with his father to Talladega, Ala., to begin serving his felony sentence. He says that when he gets out of prison, he hopes to become a PTSD counselor, in order to prevent more cases like his.