Azadeh had to get away. The young Iranian-American was convinced that her phone was tapped. Someone, the CIA maybe, was eavesdropping. She felt anxious. It no longer seemed safe in her mom’s house. What she desperately needed was a long stroll alone to think her way out of this mess.

She walked for hours, pacing the streets of downtown Tacoma. She eventually slipped off her shoes and kept walking barefoot, lost in her mind, oblivious to the blisters forming as her soles rubbed the warm concrete. It was June 2010, and she had just disappeared for three days. Her mother had been so relieved to see her return, yet so worried she’d vanish again. She once tried to explain her behavior, but couldn’t quite find the words.

“They have chosen me for a special job,” Azadeh told her mom. “I can’t talk about it, but I’ll be safe. People can read my thoughts.”

Tall, with long black hair, bronze skin, and high cheekbones, the 24-year-old turned heads as she wandered into Tacoma’s gritty Hilltop neighborhood. Her solitary meandering stretched late into the evening, but she didn’t stop to consider that a pretty girl alone in a sketchy area after dark might be in danger. The danger was that the aliens could snatch her up at any minute, she thought.

J. Bowen, Azadeh’s mother, repeatedly called the police to report her youngest daughter missing. The cops picked her up eventually, but she refused to return home. They took her instead to a recovery response center operated by OptumHealth, the Minnesota-based corporation that manages Pierce County’s mental-health services. The facility offers 24-hour psychiatric crisis-intervention services, with room for 16 people to stay overnight in a medically supervised environment. But Azadeh didn’t want to stay. She wanted to keep walking.

After a few hours in Optum’s recovery center, Azadeh called a taxi to take her downtown, where she resumed pounding the pavement. She eventually returned home, but the sequence of events was repeated the next day, and again the day after: Home. Wander. Police. Each time she ended up in temporary treatment, and each time she left abruptly, refusing to take her medication or make an appointment to see a therapist. Meanwhile, Bowen was worried sick that the next time her daughter walked out the door would be the last.

Azadeh began to show signs of paranoid schizophrenia— hallucinations, delusions, anger, anxiety, suicidal thoughts—shortly after she turned 19. She inherited her complexion from her Persian father, while her American mother’s side of the family handed down a history of mental illness, mainly bipolar disorder. Once an outgoing, creative type who apprenticed at an art gallery and helped produce an indie horror film, she would disappear for long periods with little recollection of where she went or what happened. She came back once in a daze, saying she’d met God—he was driving a pickup truck, he gave her a potion, and they had sex. Other times she became irritable, occasionally lashing out.

“One day she came in my bedroom and hit me,” Bowen recalls. “It was so out of character, it was frightening. We thought, ‘If she’s doing this, what wouldn’t she do?’ At that point we started hiding the knives, because she said to the police one time she was thinking about getting a knife.”

Azadeh’s descent into mental illness coincided with a tumultuous time in Pierce County health care. After the state legislature slashed millions of dollars in funding for mental-health services, the Tacoma region opted to become the first area in the state to put their local mental-health operations in the hands of private business. OptumHealth, typically shortened to just Optum, was chosen in 2009 to coordinate the county’s crisis and psychiatric services. As incentive to do the job well, Optum is allowed to keep for administration and profit 10 percent of the $54 million in state funds dispersed annually to Pierce County.

In an era when both public agencies and private companies are expected to do more with less, Optum consolidated and cut costs. The key component of the belt-tightening was a sweeping overhaul of the county’s approach to mental-health care. Under the old model, troubled patients like Azadeh were more often involuntarily committed to the state mental hospital, where they faced lengthy—and costly—stays. Optum, on the other hand, began preaching “recovery and reintegration into the community.” In other words, a stretch at the hospital is the absolute last resort.

“Their focus is supporting individuals in a manner that will allow them to continue on their road to recovery,” says Tim Holmes, the administrator for behavioral health at Puyallup’s MultiCare Good Samaritan Hospital, an Optum contractor. “It’s a philosophical shift that’s at the core of these changes.”

On Optum’s watch, Pierce County has experienced a major decline in the number of involuntary commitments to the state mental hospital, and the average number of days spent by county residents in psychiatric facilities fell to nearly 40 percent below the state average. Those outcomes saved millions, and Optum was widely touted for its successes. With the state’s long-term budget outlook still bleak, Optum’s bottom-line-focused approach is enticing to some state and local officials, and the company is now working to expand its presence in Washington.

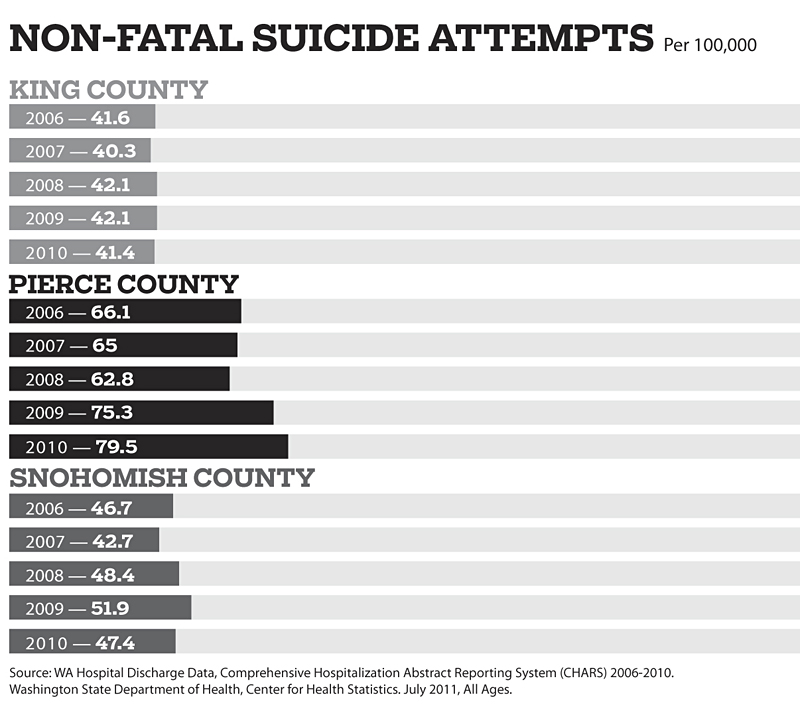

But while some of Optum’s results look good on paper, several troubling developments have coincided with the company’s brief reign in Pierce County. Both suicides and suicide attempts have steadily increased countywide since Optum took over in 2009. The number of mentally ill people booked into the Pierce County jail (formally, the Pierce County Detention and Correction Center) in downtown Tacoma has risen to the point that one official says it has become “a de facto psychiatric facility.” And, although fewer people are being hospitalized for mental illness, sources say some patients in dire need of long-term psychiatric care are frequently turned loose or pawned off on King County so that Optum avoids footing the bill.

Unwittingly caught up in this public-to-private sector transition, Azadeh was constantly shuffled through the system, says her mother, never getting the help she desperately needed to get her life back on track. The family’s story is a shocking illustration of the fallout caused by budget cuts to mental-health services and the tactics employed by Optum in Pierce County to offset those cuts.

“They kept her in this kind of holding pattern where she didn’t get any real treatment,” Bowen says. “I said to one of the mental-health workers, ‘If you don’t treat her, she’s going to end up homeless.’ She said to me, ‘Well, there are lots of homeless people.’ I’m like, ‘Thank you, but this is my daughter.’ “

Cheri Dolezal, executive director and CEO of Optum’s Pierce County operation, couldn’t speak directly to Azadeh’s case, but she emphasizes that Optum’s goal is to stabilize patients in the least restrictive setting possible. “If you listen to a person, they’ll tell you what they need,” Dolezal says. “Sometimes they think they need to be hospitalized because that’s the way the system is, when in actuality there’s lots of things you can do in the community to help them feel safe, provide space for them to recover, and get them the support they need.”

But Bowen says waiting for Azadeh to ask for help was like waiting for someone in a coma to wake up and ask for medicine. To improve her level of care, Azadeh’s family ultimately took an extraordinarily drastic measure: They sent her to live with her father in Iran.

“We’d had enough of constantly calling the police and mental-health workers—months of hell not knowing where she was, or what she was doing, or why,” Bowen says, taking a long, exasperated pause (the family requested pseudonyms in order to protect their medical privacy, as well as the safety of individuals currently living in Iran). “It’s kind of backward. I had to take my daughter there to save her life.”

Facing a massive budget shortfall in 2010, Washington governor Christine Gregoire issued an ultimatum to the state legislature: Slash spending by 6.3 percent—about $3 billion—across the board. Lawmakers obliged, and, at least on the surface, it seemed as though the state’s business continued as usual. But two years down the road, a deeper look shows that some crucial agencies were hamstrung.

When it comes to mental-health services, Washington is divided into 13 autonomous Regional Service Networks, or RSNs. The bulk of their funding is federal, in the form of Medicaid, which the state matches dollar for dollar. In King County—and every RSN outside of Pierce County—the budgeting and mental-health services are managed by public agencies, not for-profit companies like Optum.

Amnon Shoenfeld, the director of King County’s Mental Health, Chemical Abuse and Dependency Services Division, says losing supplementary financial support from the state is especially painful because the RSNs have some leeway as to how that money can be spent. Medicaid cannot be used to pay for involuntary commitments, the mental-health professionals who evaluate people, or the legal costs associated with certain types of hospitalization.

According to Rick Weaver, a consultant to the state’s Department of Social and Health Services’ (DSHS) Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery, state dollars fund crisis response, residential treatment, and outpatient care (hospital or clinic visits that last fewer than 24 hours) for the most needy. Or at least that’s how it used to be. “In almost all parts of the state, there are no outpatient services left for people not on Medicaid,” Weaver says. “If you’re indigent and on the street and not on Medicaid, the ability to get outpatient mental-health services is essentially nonexistent.”

Washington is certainly not alone in its decision to shred the social safety net. According to the National Alliance for Mental Illness, since 2009, states across the country have trimmed $1.8 billion from their budgets for spending on children and adults living with mental illness.

Of course, times aren’t so tough for everybody: OptumHealth generated $5 billion in revenue in 2011, according to an estimate from the business intelligence group GlobalData. In addition to managing public mental-health services in New Mexico, Utah, and other states, the company’s website says they offer “unique healthcare solutions to employers, health plans, public sector entities, and over 58 million individuals.”

A “unique healthcare solution” was exactly what the doctor ordered for Pierce County in 2007. Beset by costly lawsuits and bureaucracy, the Pierce County RSN was struggling even before the harshest wave of state budget cuts hit. Such was the situation when they took the unprecedented step (in Washington at least) of privatizing their mental-health system. The state managed the RSN for stretches of 2008 and 2009, but Optum beat out three other bidders for the contract and assumed control on July 1, 2009.

Optum Pierce County CEO Dolezal says she looked at the state cuts, about $6.2 million worth of which affected Pierce County’s mental-health services, as a chance to increase efficiency. “I don’t say, ‘We have a crisis, oh woe is me, there’s a budget shortfall,’ ” Dolezal says. “To me, I present it as an opportunity to really take this and figure out how we can do this and make sure people continue to get served.”

Dolezal, 64, is the former director of the Clark County RSN. One of her first moves was to meet with the public, administrators from Pierce County’s four mental-health clinics, and other stakeholders. The goodwill gesture paved the way for sweeping changes. More than 130 employees from Pierce County Human Services were laid off, including case workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, and nurses. Optum also compelled Tacoma’s four mental-health facilities to compete against each other for contract services.

“They talked to everybody and did interpersonal work before they made changes,” says Ginny Peterson, former president of the Pierce County chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “Kudos to them on that; they made changes and are holding people’s feet to the fire. There is accountability now.”

Optum gave the 24-hour recovery response center a face-lift and revamped the county’s mobile outreach unit, outfitting a 38-foot van for a variety of on-the-spot medical services. They also established a “Peer Bridger Program,” which connects patients with other individuals recovering from mental illness trained to work as counselors.

By some measures, Optum has been an improvement on the old system. It trumpets in press materials the fact that, despite the decrease in state funding, the RSN served 15,262 patients in 2010, a 25.9 percent increase over 2009. A Seattle Times article from August 2009 credits Optum’s mobile outreach van for “a 19.5 percent reduction in hospitalizations,” which saved more than $1 million.

Optum’s Peer Bridger program was singled out for praise by the nonprofit Medicaid Health Plans of America Center for Best Practices. According to Optum, the program has served 125 people since July 2010. Before Peer Bridger, those 125 people accounted for 202 hospitalization admissions, but only 42 afterward—a 79.2 percent reduction that reportedly resulted in savings of $550,215.

But perhaps the most striking statistic from Optum is the drastic reduction in the number of individuals involuntarily detained in mental-health facilities. From 2008 to 2010, nearly every other county in the state detained roughly the same number of people per year as they had previously, according to the most recent figures available from DSHS. But in Pierce County, detentions per year dropped from 587 to 402, and “revocations”—people committed for 90-day stays in the state mental hospital—plummeted from 58 per year to 13.

Dolezal says Pierce County was simply detaining far too many people. In her view, many individuals can be convinced to seek voluntary care through Optum’s new initiatives, such as the 24-hour recovery response center or the mobile outreach van. Not only are those options less restrictive, they are also far less expensive. Medicaid will not pay for many of the costs associated with involuntary commitment, so the process tends to drain a disproportionate amount of the ever-dwindling state-only funds.

Technically, Optum and other RSNs should have no influence over which people are involuntarily detained. According to the letter of the law, when someone is referred to the state mental-health system, a Designated Mental Health Professional (DMHP) employed or contracted by the RSN evaluates the patient and decides whether he or she should be held for 72 hours. The key criteria are whether the person poses “an imminent likelihood of serious harm” to themselves or others, or is “gravely disabled.” A superior court judge then decides if the detainment should extend for another 14 or 90 days.

But, barring the “imminent likelihood of serious harm,” the law also requires DMHPs to advise people of their right to be discharged if they agree to seek voluntary treatment. Dolezal says Optum has made the voluntary aspect of the law a point of emphasis, educating workers about “other diversions to stabilize [individuals] in that moment, and help reintegrate them into the community.”

Optum’s control of the purse strings also gives them significant influence over the way Pierce County’s four mental-health treatment centers do business. The facilities must bid for contracts to work with patients from places like the Pierce County jail. At Good Samaritan Hospital, Holmes says Optum “watches our trends and our rates” and reviews cases to see whether hospitalization could have been avoided, but ultimately, when it comes to involuntary commitments, “they know that’s our independent authority.”

Optum’s strategy has succeeded in sharply cutting costs, but has also raised concern. Shoenfeld worries that something tragic is bound to happen when people with serious mental issues, who elsewhere in Washington might be involuntarily committed, are allowed to roam the streets. “If you make a mistake, it can have very real consequences,” he says. “But at the same time, they don’t want to force someone into a hospital if outpatient [treatment] can work.”

Asked about the delicate balance between public safety and patient needs, Dolezal says Optum errs on the side of freedom. “Are we perfect?” she says. “No. But I think we’re willing to take risks. We’re willing to take risks for the sake of these individuals.”

Optum’s strategy sounds like a win-win: Keeping people out of an insane asylum is not only more humane, it saves tax dollars. But when the messy unpredictability of mental illness comes into play, things aren’t always so straightforward.

Seated in a coffee shop a few blocks away from the family’s west Tacoma home, Bowen and her eldest daughter warmly recall what Azadeh was like before she got sick. She was kind and generous, they say—one Christmas she bought everyone “gift card” donations to local charities instead of traditional presents. She worked as a babysitter, at a clothing store, and as a waitress at an Indian restaurant, but her passions were poetry and art. “She organized an art show that made over $3,000,” Bowen boasts, chuckling at the memory. “It was based on sadomasochism. I said, ‘Well, I’m not crazy about the theme, but if it sells . . . ‘ “

Azadeh’s older sister says the changes in her younger sibling’s personality were subtle at first. Then she became argumentative, anxious, and paranoid, eventually losing touch with her longtime friends. Once she was picked up for pounding on the door of an acquaintance from school, telling police she thought there was a computer inside the house controlling her thoughts. (The acquaintance’s family didn’t follow through on a restraining order, court records show, and no criminal charges resulted.)

“I empathize with the cops,” Azadeh’s sister says. “They’re only allowed to do so much, and with some you could tell they wanted to do more. They were called so many times for such non-life-threatening things, but it was the only thing we could do.”

After the string of disappearances in June 2010, Azadeh’s family finally convinced her to resume taking medication. It was not easy. The pills caused her to gain weight, and she complained that they left her feeling “numbed out.” With dark red hair cropped short, oval-framed glasses, and a lifetime’s worth of worry lines etched into her 59-year-old face, Bowen recalls waging “a daily battle of wills” with her daughter. “You can’t get mad,” she says. “You can’t get angry or she’ll just run away again. I got her back on the meds, and she started getting a little well, and then she decides she doesn’t want to take them anymore.”

An incident in early 2011 changed everything. Azadeh left home early one evening planning to go shopping, but instead ended up aboard a bus to Seattle. After she vanished the first few times, Bowen figured out how to track down Azadeh using the GPS function on her cell phone. Dialing in the coordinates, Bowen pinpointed her daughter’s location: a seedy stretch of First Avenue South in Georgetown, specifically La Hacienda Motel, made infamous last year when Seattle police arrested the owner for allegedly selling guns and meth and allowing prostitution in the rooms.

Bowen hopped in her car and sped up I-5, arriving shortly after 11 p.m. The person working La Hacienda’s front desk knew right away which guest the panicked mother was after. Azadeh had made a scene in the lobby a few hours earlier, bursting into tears upon realizing she’d misplaced her ID card.

Bowen eventually got her foot in the door to Azadeh’s room and pleaded with her to come home. But Azadeh wasn’t going anywhere. As an adult, she was free to do as she pleased, and she had more than enough money to rent a room—about $3,000 that she had been saving to buy a new video camera and perhaps move to California to study digital media. Bowen left her name and number at the front desk with instructions to call in case of emergency. Her phone rang the next morning.

“They said she was walking around half-naked,” Bowen says. “She had been asking people to buy pot for her, and just throwing her money around.”

Bowen dialed King County’s crisis line, only to be informed that the local mental-health professionals were powerless to intervene unless Azadeh got arrested, failed to pay her bill, or threatened to harm herself or someone else. So when the motel called Bowen the next day to complain that Azadeh was having another episode, she summoned the police. “It’s a pretty sad state of affairs when you hope your daughter is arrested so she can get treatment,” Bowen says.

By the time police responded, Azadeh had left the hotel and was drifting around the Ave in the U District. Somehow she managed either to spend or lose all but $400 of her savings. King County mental-health workers took her out for a cup of coffee, talked about her situation, and, when she refused to check herself into a hospital, recommended she be involuntarily detained for 72 hours.

Although the circumstances of Azadeh’s Seattle misadventure are unique, several sources say she’s hardly the first Pierce County resident to end up detained in King County since Optum arrived on the scene.

Shoenfeld is an outspoken critic of Optum. It rankles him that Optum keeps such a large cut of state funding for profit (the company netted $5.4 million in 2010) while publicly managed RSNs are obligated to keep administration costs to a minimum, using as much taxpayer money as possible for services. To wit, King County keeps only 2.5 percent of public funds for management costs, versus 10 percent for administration and profit withheld by Optum.

When the company submitted a proposal to DSHS last year suggesting the state downsize from 13 RSNs to three, with Optum controlling more of western Washington, Shoenfeld penned a response that called into question some of their supposedly positive outcomes. (Although not explicitly stated in their proposal, the implication is that Optum would take over everything south of King County.) He noted that although Optum boasted that they served 15,000 people in 2010, nearly 26 percent more than the state-managed Pierce County RSN did in 2009, they neglected to mention that in 2008 the RSN provided services to more than 18,000 people—18 percent more than Optum’s total. Since 2008, King County has seen a corresponding 18 percent increase in its number of patients.

“We’ve definitely had people we’ve had to commit who were Pierce County residents and came up here,” Shoenfeld says. “There’s a profit incentive for Optum not to hospitalize people. It’s a natural area to look at to make sure that’s not driving decisions about what needs to happen when people with mental illness are presenting a danger to themselves or others.”

One Pierce County therapist, who requested anonymity in fear of a backlash for speaking out about Optum, says it has become so difficult to get detentions and involuntary commitments in Pierce County that patients are sometimes told to take a taxicab to King County so that they can get treatment. “It’s literally like we’re shipping them across the border,” the therapist says. “The length of [hospital] stay is down, but in five days they’re back in the community to attempt suicide again.”

The therapist also claims that, though the commitment process is supposed to be autonomous and objective, Optum has virtual control of who ends up in a respite bed, who gets turned away, and who gets recommended for an intensive stay at Western State Hospital in Lakewood. “We have to go to Optum for everything,” the therapist says. “Pretty much, Optum is God, and says what we can and cannot do.”

Optum’s track record in other states supports such claims. In New Mexico, where Optum manages $338 million worth of mental-health contracts statewide, the company was fined more than $1 million for failing to reimburse local providers in a timely manner, and reprimanded for ignoring psychiatrist recommendations to hospitalize certain high-risk mental patients. As punishment for the latter, part of Optum’s contract for juvenile forensic evaluations in New Mexico was altered last year.

“All the decisions are made based on the profit motive,” says Susan Cave, the director of the Santa Fe County Sheriff’s Department’s forensic evaluation team. “People are denied services until they end up in jail or prison, where it’s really expensive. It’s a sad, sad state of affairs.”

Santa Fe district court judge Michael Vigil tells of one case in which a child with a lengthy history of violence attacked his mother. Optum wanted to send him back home to live with his family and younger siblings, while the judge and mental-health professionals familiar with his background felt he should be hospitalized for safety reasons. Optum relented in the face of a court order, but the youngster was stuck in juvenile detention while the conflict was resolved. “It was almost like we were going to go through this less-restrictive process just to have them fail, and then we could move to the next level,” Vigil says. “My position was, we can’t do that with children’s lives.”

And lives are certainly at stake: In 2008, there were 508 attempted suicides—a rate of 62.8 per 100,000 residents—in Pierce County, according to hospital admissions data from the Department of Health. Those numbers increased to 603 and 75.3 in 2009, and again to 636 and 79.5 in 2010. With the exception of Skagit County, where suicide attempts also spiked over the past two years, the suicide-attempt rates for western Washington counties have remained comparatively constant. Even more unnerving, the number of successful suicide attempts in Pierce County steadily increased from 2008 to 2011, from 124 per year to 145, according to the Pierce County medical examiner.

Dolezal says the spate of suicides at Joint Base Lewis-McChord partially skewed the data, and notes that Optum has erected billboards to educate the public about the new crisis-hotline number. “We’re actively doing something,” Dolezal says. “But there’s no excuse for it.”

After a brief stay in Seattle’s Northwest Hospital and Medical Center, Azadeh was sent back to Pierce County, where she was placed in Telecare, an evaluation and treatment center in Tacoma contracted by Optum. The facility is akin to a halfway house for mental patients, allowing stays of up to 17 days for people who fit the criteria for admission to Western State Hospital—the largest and most care-intensive mental facility in the state—but might benefit from a somewhat less-restrictive environment. According to Telecare’s website, the staff “strives to awaken the hopes and dreams of the individual” and teaches “self-responsibility in order to foster their recovery and successfully transition them back to lower levels of care.”

But, according to Bowen, even though Azadeh’s condition did not improve, her daughter was relocated to a group home after two weeks, where she was free to come and go as she pleased.

“It got to the point where [the Telecare staff] said, ‘She’s eligible to go to Western State, but we’re not going to put her there,’ ” Bowen says. “Then she starts getting worse, she’s more paranoid, saying there’s aliens and CIA agents living upstairs. But when I mention this to the social worker there, he says ‘Oh, it’s too late to petition [for a transfer to Western State]; we can’t do a thing right now.’ “

When a judge decides that a mentally ill individual needs to be involuntarily committed for 90 days, state law says that person must go to a state mental hospital, typically Western State. But getting in these days is easier said than done.

Like nearly every other state entity, Western State is strapped for cash. Although still Washington’s largest mental institution, its bed capacity has dropped from 777 to 517 over the past five years due to budget cuts. Making matters even more difficult, the hospital is short-staffed on psychiatrists, who struggle to handle even the reduced number of patients.

When the legislature saw fit to cut spending and, consequently, reduce the number of beds at Western State, the state’s population did not suddenly become more mentally stable. Now the lack of vacancies has created a logjam of sorts: Patients waiting for space to open up at Western State are housed in smaller, less care-intensive mental hospitals—such as Fairfax Hospital in Kirkland and Navos Mental Health Solutions in West Seattle—or, increasingly, in the emergency rooms of major hospitals like Harborview.

Former King County Executive Randy Revelle, now senior vice president of the Washington State Hospital Association, says Washington ranks near the bottom nationally in number of mental-health beds per capita. Revelle is leading a Task Force on Inpatient Mental Health, seeking solutions to the dilemma. “We have a serious problem,” says Revelle, who recently announced he’d be retiring by the end of the calendar year. “People can’t get into Western State, can’t get into one of their local mental-health facilities, and end up waiting in the halls of our hospitals without adequate support, without adequate care, and being put into rooms not really made for psychiatric care. It’s a real mess.”

The situation is so dismal that in 2010 the state legislature unanimously passed a new law (HB 3076) that allows mental-health workers to solicit input from family members, friends, neighbors, etc., about whether a person should be involuntarily detained. But because more people would assuredly be sent to Western State, the lawmakers delayed enacting many provisions until 2015 to avoid the extra costs—an estimated $12 million for a new ward, additional staff, and operating expenses.

At Harborview, Psychiatric Nurse Manager Darcy Jaffe says mental patients sometimes wind up on stretchers in the hallways when the hospital reaches capacity. There is a unit devoted specifically to psychiatric care, but only 10 beds are available, and the daily treatment costs are nearly double that at Western State, with the King County RSN forced to pick up the tab. “We’re taking people from five states for trauma,” Jaffe says. “That part of ER starts to fill up, and it turns into chaos. Everybody knows that patients are not getting the care they’ve been ordered by the court to receive.”

Most RSNs have continued to involuntarily detain roughly the same number of people they had prior to 2010—with two key exceptions: King County’s detentions jumped 28 percent over the past two years, while Optum’s detentions in Pierce County fell 31 percent.

Shoenfeld notes that King County is unique because it is home to several large mental-health facilities, and has, by far, the largest homeless population in the state. He also says the county lost “well over $20 million” in mental-health funding over the past four years as a result of state cutbacks, leaving little left over for education, outreach, case management, and other preventative services. “A lot of those programs helped get people out of the hospital or kept them from going there in the first place,” Shoenfeld says. “We have to cut, and we end up spending more and more on inpatient [services]. It’s really been a vicious cycle, and it’s not saving anybody any money at all.”

Yet Optum is facing similar challenges in Pierce County, and they seemingly have devised a solution. Dolezal says budget realities demand expanded use of treatment alternatives—less-rigid, less-expensive facilities like Telecare or the Recovery Response Center where Azadeh ended up. “This isn’t where the country is going—’Let’s see how many people we can detain and put in the hospital,’ ” Dolezal says. “The country is going to the rights of the individual.”

That may be true, but Optum’s new cost-cutting model for mental health only works if their intermediary treatment facilities are absorbing all the patients who previously would have wound up at Western State. And judging by one critical measure—the number of mentally ill people being booked into the Pierce County jail—Optum’s alternatives have not picked up the slack.

One hundred and forty-one people were referred for involuntary commitment at the Pierce County jail last year, compared to 82 in 2008 before the Optum era began. Judy Snow, the jail’s mental-health manager, says she has seen “a marked increase” in the number of inmates with mental illness, and recidivism—mentally ill inmates released and rebooked for another offense—has also been on the rise.

“They’re pleased with the reduction in hospitalizations,” Snow says of Optum. “I agree, hospitalization is not the answer. But if you have a reduction without community support, they’re going to end up in jail, and that’s what’s happening. The jail is becoming a de facto psychiatric treatment facility.”

A 24-year veteran of the Pierce County mental-health system and the top mental-health official at the jail since 2000, Snow says Optum tried to address mental-health issues at the jail in 2009. Specifically, the company implemented a policy under which each new inmate is scanned through a database to see if they’ve previously come in contact with the mental-health system. Three Tacoma mental-health centers have jail liaisons who work with Snow and her staff to transition qualifying inmates out of jail and into mental facilities. But, according to Snow, those measures have not met the rapidly increasing demand for psychiatric services at the jail.

Barely five feet tall, even counting her large poof of blonde hair, Snow leads a tour of the jail to illustrate the depth of Pierce County’s mental-health crisis. The psych ward is on the third floor, separated from the main hallway by two sliding gates with thick steel bars. The portals clank heavily as they open, and, spectacles perched on the end of her nose, Snow shouts “Clear!” to the guard on duty, who promptly locks the doors shut behind her with the press of a button.

On the other side of a Plexiglas barrier, men in gray and pink smocks lounge glumly around a table in a common area. A young-looking white guy with a short, mullet-style haircut approaches the partition and stares at the unfamiliar visitors with an utterly blank expression. A concrete wall separates the open space from a higher-security area containing several intense-looking cells outfitted with wire-mesh-and-Plexiglas doors so that the occupants are never out of the guards’ line of sight.

“They’re just mainly extremely psychotic,” Snow casually says of the occupants. “Everybody in here is just unable to be around anyone else.”

“It’s a very noisy unit,” the guard chimes in. “You get a lot of people kicking and screaming and that type of thing.”

“Can you imagine having a mental illness in this environment?” Snow asks. “The jail is not a treatment facility, nor should it be. It’s tragic. These are very sick individuals.”

According to Snow, the Pierce County jail has room for roughly 1,400 inmates, and on average about 20 percent of them have major mental-health issues. She says administrators are “looking at ways to increase our mental-health high-intensity cells” to alleviate overcrowding, and she is optimistic that Optum will follow up on its vow to make additional changes after a key jail service contract with local hospitals is awarded in October.

In the meantime, Snow says that while Optum has succeeded in sending fewer Pierce County residents to Western State Hospital, many of those gains are superficial. For instance, Snow points out that since 2009 there’s been a roughly 25 percent increase in the number of mental-competency evaluations performed at the jail, indicating that many of the patients Optum claims are receiving treatment in the community are likely ending up behind bars instead.

“To paint a rosy picture of Pierce County is not accurate,” Snow says bluntly. “We need additional services.”

Toward the end of the tour, Snow stops at the offices of the jail’s mental-health team. The facility has on staff eight certified mental-health professionals who are independent from Optum and the Pierce County RSN, but who work closely with the county DMHPs during the detainment process. When asked about the policies implemented by Optum and offered anonymity, staff members don’t hold back their opinions.

“I’ve been here a long time and this is a real low point,” one says.

“We had one person where [the DMHP] wouldn’t detain them, but then jail wouldn’t release them because they were so psychotic,” another recounts.

“[Optum employees] don’t use clinical words like ‘depressed’ or ‘paranoid’ or ‘hallucinating,’ ” the conversation continues. “It’s all euphemisms—’Oh, they’re just having a bad day.’ “

“Maybe I’ll put that on my next evaluation form,” a colleague jokes in response. ” ‘This person is having a very bad day and needs to be detained for 90 days.’ “

Throughout 2010 and 2011, as Azadeh continued to battle her inner demons, she could increasingly be found praying inside a mosque not far from her neighborhood. She would stay all day, on some occasions begging the staff to let her remain after closing and spend the night. The mosque leaders helped the Bowen family by summoning a Muslim doctor to tell Azadeh that the Quran did not forbid her from taking pills.

Azadeh’s parents divorced when she was 9. She had been raised in Iran, but after the split she came to Tacoma with her older sister and Bowen, who eventually remarried. Though hardly a devout Muslim, Azadeh was drawn to Islam, and relished the infrequent trips to Tehran to visit her father. She called the Iranian government “a façade” on her MySpace blog, but also posted a Deepak Chopra article that praised progressive developments in the country, noting that “two-thirds of Iran’s population consists of people under 30.”

At the mosque, Azadeh tried to convince two fellow worshippers to drive her to the airport, telling them she was sick and that the cure to her illness could only be found somewhere in Egypt or Saudi Arabia. When she mentioned moving to Iran to stay with her father, Bowen was initially mortified. “At first I said, ‘That’s a horrible idea!’ ” Bowen recalls. “If she starts acting out in Iran, she’s going to be in big trouble. If she doesn’t wear a scarf or even talks to guys in public, she’ll go to jail.”

But as time wore on, and Azadeh was repeatedly chewed up and spat out by the mental-health system, the idea began to seem less and less outlandish. Bowen lived in Iran during the ’80s and early ’90s, and says that despite the strict Islamic rule, the country has one of the best public-health systems in the Middle East. After everything the family had been through, a change of scenery—however extreme—seemed like the best option.

“Having a person in a house with mental illness who’s not getting treatment just kind of sucks the life out of you,” Bowen says. “After six years of having my daughter in my house, I was ready for the loony bin. It was so hard.”

“Mom had to hit rock bottom,” adds Azadeh’s older sister. “She knew there was no other way.”

Bowen liked that Azadeh would have support from extended family members, and, perhaps more important, that she would have no choice but to take her medication. Despite her numerous interactions with police and the mental-health system, Azadeh was never in a setting where taking anti-psychotics was mandatory.

While her mother firmly believes a trip to Western State would have stabilized Azadeh and served as a wake-up call, several mental-health officials interviewed for this story—including some not affiliated with Optum—cautioned that lengthy hospitalizations are not a panacea. Nor is Western State a particularly pleasant place to stay, as last month’s grisly murder of one patient by another showed.

“If we involuntarily commit someone, it doesn’t mean it will be helpful,” says Holmes, the Good Samaritan Hospital administrator. “It may help the immediate crisis of the situation, but it might be like doing surgery on someone when all they need is a Band-Aid.”

That is Optum’s ideology in a nutshell—appealing for both its ostensible compassion and inherent affordability. The state did not move on Optum’s recent proposal to consolidate 13 RSNs to three, but DSHS officials say they are considering a less-radical restructuring, and Dolezal says Optum is eager to capitalize. “I would love to expand,” Dolezal says. “I think what we’re doing in Pierce County should be done other places. There’s no doubt about it.”

But Pierce County officials are still on the fence about Optum. In light of the ongoing issues at the jail and the steadily rising suicide rate, Deputy Pierce County Executive Kevin Phelps says the county has “been having discussion about going back to the state.

“They assured us when we went to the RSN private-sector model, we would not see negative impacts in the community,” Phelps says. “We are starting to see some negative impacts, and we need to re-engage in dialogue with the state and Optum to see if we can mitigate those.”

Phelps recounts a recent meeting with the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department when he was told that deputies had resorted to picking up homeless people and the mentally ill and taking them to tent cities rather than to shelters or mental-health facilities. “In some cases,” Phelps says, “they are literally picking up patients who otherwise might be in facilities receiving treatment and taking them to various encampments around the county and dropping them off there.”

Stories like this help ease Bowen’s lingering doubts about sending Azadeh to Iran. “Over here, she would have ended up out on the street,” she says. “There, if the family says she’s sick and the doctor says she’s sick, she’ll have to take her medication.”

Both Bowen and her eldest daughter say Azadeh’s condition has improved in recent months. She is much more talkative and alert, they claim, based on phone conversations and their visit to Iran late last year. Through her family, Azadeh declined to be interviewed for this story. She did, however, offer one succinct comment about the state of mental-health care in Washington.

“I wish it was better,” she said.