One winter, 14 years ago, a British Columbia farmer named Neal Carter took his family on vacation to the Middle East, where he had once lived while working as an agricultural engineer. A young woman was looking after his house, which sits on a plateau overlooking the mountains of Canada’s Okanagan Valley, a stunning part of the country much like Washington’s Lake Chelan region, known for its beaches on vast Okanagan Lake, a booming wine industry, and picturesque orchards.

The Carters owned 21 and a half acres of that land, descending from their home and occupied mostly by apple trees. While the family was in Jerusalem, they heard something was amiss. “Neal, I don’t know what’s going on,” the young housesitter said to Carter by phone, “but there are TV cameras at the house this morning.”

The Carters soon found out that a group of activists opposed to genetically modified organisms had snuck onto the Carter orchard, tromping on snow as they went, and hacked into 652 apple trees.

This was 1999, right around the time of the World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, which intensified opposition to GMOs and a range of other activist causes. The hatchet-wielding would-be revolutionaries who hit the Carter orchard apparently knew that the unassuming middle-aged farmer was in the process of developing a genetically engineered apple called the Arctic.

Not that they hit their target, exactly. Presaging the misdirected firebombing that would occur two years later at the University of Washington Center for Urban Horticulture, a strike also aimed at genetic engineering, Carter says the activists “didn’t know what they were doing at all.” The trees they hacked were conventional apple varieties, not genetically engineered ones. And the damage they inflicted wasn’t lethal. The trees grew back.

Still, Carter was shaken. “Holy cow, we’ve got to be more cautious here,” he recalls thinking. He started insisting upon confidentiality among his staff, and to this day will not publicize the location of the greenhouse where he grows Arctic apples (his orchard is devoted only to conventional varieties). Nor will he disclose exactly where he maintains field trials in Washington and New York states.

Carter tells the story one bright late-October day, the sun only partially warming the nip that has already taken hold along the Canadian Cascades. A lean figure dressed in jeans, a flannel shirt, a cap, and sunglasses, the 56-year-old is sitting in a pickup truck watching an excavator pound poles for a deer fence. His 26-year-old son, Joel, who recently moved back home from Vancouver to help in the family business, is in the fields. Carter’s wife Louisa, a forester he met as a student at the University of British Columbia’s outdoor club, will soon call him in for a lunch of homegrown pumpkin soup.

Carter’s personal orchard is separate from his genetic-engineering operation, which goes under the name Okanagan Specialty Fruits. But that business is similarly small-scale and family-run, maintaining just seven staffers: Carter, his wife, a scientist, two lab technicians, and a communications and marketing team that maintains an active website.

It’s not the image you associate with GMOs, which are usually produced by huge, multinational corporations like Monsanto. Their presumed rapaciousness, and aggressive enforcement of plant patents, helps explain why biotech crops have become controversial enough to spark vandalism, firebombing, and, in a more civilized vein, the labeling initiative that Washington’s voters narrowly rejected in November.

Carter, an unabashed GMO advocate, does not criticize Monsanto. At the same time, he says, “We want to show people this can be done by a small company.”

Carter presents himself as a new breed of GMO producer. In the past, he observes in a video on the company’s website, GMOs have “been all about agronomic benefit and reducing costs for farmers.” The impact on farmers is perhaps debatable, with some praising the efficiencies provided by genetically engineered crops and others chafing at the domination of biotech multinationals. There is no question, though, that such crops—now contained in an estimated 80 percent of all processed foods in the U.S. and generating a multibillion-dollar market—have proved lucrative for their producers. Yet Carter asserts that the Arctic apple will, in contrast, “offer something for everybody”—including, most importantly, consumers.

The Arctic’s signature trait is that its flesh does not brown when cut or bruised. In Carter’s view, the ability to slice an apple and have it stay white for hours (hence the name, evocative of white snow) is an important breakthrough, both for sliced-fruit purveyors and parents who put apples in their children’s lunches. He casts the Arctic as an enticement to healthier eating and a potential boon to the apple market, in the footsteps of “the baby-carrot model”: Just as the convenience of baby carrots made them a ubiquitous snack in a way regular old carrots never were, so sliced, nonbrowning apples could take off among the public and send apple sales soaring, Carter holds.

In a TED Talk last year, Carter put the Arctic in the context of a “second wave” of biotech crops, all of which he said would favor consumers. In particular, he pointed to developing GMOs with health benefits, such as the vitamin-enriched “Golden Rice” and the similarly fortified cassava that are in the works. Other genetically modified crops under research include calcium-enhanced lettuce; a purple tomato high in cancer-fighting antioxidants; and a potato low in a believed carcinogenic called acrylamide. By contrast, the 100 or so GMOs already approved by regulatory authorities—including numerous varieties of corn, soybeans, cotton, and sugar beets—are concentrated on herbicide and pest resistance.

But even as the Arctic gets closer to becoming the first new-wave GMO on the market—the U.S. Department of Agriculture released favorable assessments last month, and this week finished a second, final round of public comments—many GMO critics have made it clear that they are just as hostile to this wave of biotech crops as they are to the first.

“Frankenapple: Bad news no matter how you slice it,” read the headline of an anti-Arctic article published in April by the Organic Consumers Association. Indeed, Lisa Archer, director of Friends of the Earth’s food and technology program, says that recent transgenic products like the Arctic apple have ignited a “whole new level of concern,” since most are intended to be eaten as a whole food. Older GMOs such as corn and soy are typically processed for their derivatives and mixed with a lot of other ingredients to create packaged and canned foods.

Undoubtedly the biggest blow, though, has come from a surprising source: Carter’s own peers in the apple industry. The U.S. Apple Association, the Northwest Horticultural Council, and the BC Fruit Grower’s Association have all urged regulatory authorities in the U.S. and Canada to deny approval to the Arctic. In a letter to the USDA, the Northwest Horticultural Council compared the “threat of the Arctic apple” to “an invasive pest species.”

If the Yakima-based Horticultural Council is right, this threat is of particular concern to Washington, by far the largest apple-grower in the U.S., with 146,000 acres devoted to the fruit. (New York, next in line, has only 42,000 apple-bearing acres.)

Whether this perceived threat comes from a small British Columbia farmer or a giant multinational makes no difference, according to Horticultural Council president Christian Schlect. The modest size of Carter’s company “doesn’t cut any ice at all,” he says.

Yet the Council and other industry groups say they have no concerns about the safety of eating Arctic apples. From the standpoint of their members’ livelihood, they’re worried about something even more dangerous: public opinion.

Walking around his orchard

with two dogs trailing him, Carter seems like a typical small farmer. Some apples are still on the branches in October, even though harvest time is over. Carter blames a June hail that left holes in the McIntosh apples that droop from trees lining the long road that leads to his house, rendering the fruit unsellable.

He shares another bit of bad news: Some years back, a rotting disease hit the cherries that he also grows in small amounts. He spent $30,000 in labor costs to harvest the cherries, which looked fine on the trees. Less than an hour after being picked, their skins began to wither and slip off. He pulled up all his infected cherry trees and replanted Ambrosia apples.

“That’s the kind of decision you have to make, and make quickly,” he says.

When he turns to his biotech venture, though, Carter exhibits a side not so common among farmers. He talks intently about DNA sequences, RNA coding, and polyphenol oxidase, or PPO—the enzyme responsible for browning in fruit. He’s up on research papers that have implications for his venture, whether they hail from Australia or China. He dismisses the few articles that provide fodder for GMO opponents as “junk science.”

It’s ironic that Carter, who grew up in Vancouver, originally didn’t even want to go to college. His parents persuaded him to try it, but he took an extended break after a year to bike and hitchhike through Europe and the Middle East. In Egypt, he saw farmers getting the water they needed for their fields by scooping it from the Nile with a simple tool, “essentially a bucket on the end of a bamboo pole,” he recalls. It got him thinking about a career that would bring modern tools and technology to developing countries. So when he returned to college, he decided to go into agricultural engineering.

After college and marrying Louisa, he spent a stint on an uncle’s farm. “We thought it was a pretty amazing life,” he says. He liked growing things and the idea of being his own boss. But he found opportunity elsewhere in AgroDev, a big agricultural-engineering firm that worked on projects all over the world.

Carter says he provided technical assistance to a 100,000-acre sorghum and sesame farm in Sudan that used “dryland” techniques to conserve moisture; worked on a crop-diversification project in Bangladesh; and helped build a number of farms in the Middle East. “I was back and forth to the Middle East 30 times before I moved there,” he says. He settled his family in Jordan, where he says he worked as AgroDev’s Middle East manager.

The expat life grew old, though. “You know, I think it’s time to build a farm for ourselves,” Carter says he told his wife. In 1995, they bought property in Summerland, one of the smaller towns in the Okanagan Valley.

Ron Vollo, an apple farmer already there, notes that Carter was “pretty green” when he started farming. He did not come from a farming family; Carter’s father was an electrical engineer. But Vollo was impressed with the newcomer’s energy. As they became friends, Vollo learned that Carter had cycled competitively in college and afterward. From 1975 to 1986, Carter raced on teams run by the bike companies Bianchi and Miele. After a day of farming, Carter could often be seen biking around Summerland or taking a run. On vacations, he and his wife went on vigorous mountain-biking excursions through the American Southwest.

His energy could also be seen in his entrepreneurial activity. From the beginning, Carter didn’t just run his orchard in Summerland. He started a wide-ranging business that offered international consulting, designed specialized farm equipment, and sold netting to farmers plagued by birds. Then he turned his mind to biotech.

Summerland is distinguished by a major research center operated by the Canadian government that helps to develop new varieties of crops. In the mid-’90s, David Lane, a former researcher there, got a call from Carter.

The scientist and the fledgling farmer talked about a number of ideas, but one stood out. If you want to reduce food waste, Carter remembers Lane telling him, you should take a look at work being done in Australia on polyphenol oxidase, the browning enzyme. Government scientists there had found a way to turn off that enzyme in potatoes through transgenic means.

Carter was intrigued. When cut, “potatoes brown like crazy,” he says. He thought that was a problem for chip makers like FritoLay. So he hit upon the idea of developing a commercial variety of non-browning potatoes and licensing the rights to FritoLay. Although based in Summerland, he was still working as a consultant for AgroDev at the time, and the company was interested in the idea too, he says. Carter traveled to Australia to meet with scientists who had done the pioneering work.

Then, Carter says, AgroDev was bought and lost interest in transgenic potatoes. “So we decided to focus on tree fruits,” he says. As with potatoes, the plan revolved less around growing genetically engineered apples—although he plans to do that too on his orchard—than around licensing rights to other farmers.

It’s a model that has come under fire by critics of the way genetic engineering has turned crops into intellectual property. But Carter points to a field of conventional Ambrosia trees behind him, and says that he had to pay licensing fees to the apple’s inventors, B.C. orchardists Wilfrid and Sally Mennell—at a cost of $3,400 an acre. “It’s the world we live in,” he says.

There has been a dramatic emergence of new apple varieties in the past 20 years, as the primacy of the Red Delicious has waned and the public has clamored for sweeter, crisper, firmer fruit. Many of these new varieties have been patented in accordance with the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970, confirms Mark Seetin, director of regulatory and industry affairs for the U.S. Apple Association. He says there are some varieties, like the Pink Lady, that farmers can’t grow without belonging to a managed consortium that charges fees and monitors quality.

Carter maintains that the fees he will charge for the Arctic—$1,500 for an acre’s worth of trees—will be on the “low end.”

Having drawn up a plan, the farmer talked to his grower friends to drum up support and investment. “Everyone was pretty enthusiastic,” recalls Vollo, who went in on the venture. “The public seems to like things easy,” he says, speaking of the potential he sees in non-browning sliced apples. He thinks they can create a market among people who don’t eat fresh apples.

Carter founded Okanagan Specialty Fruits and eventually attracted some 45 shareholders. He also got financial and scientific support from the government research center in Summerland. In fact, his company’s lab was housed within the center for a number of years.

The first challenge Carter faced was scientific. It turned out that it was not as easy to silence the browning enzyme in apples as in potatoes.

The method used is called RNA interference, or RNAi for short. This is a technique different from the one used to create many transgenic crops, which are produced through the insertion of genetic material from other plant species, animals, or even viruses to produce desired traits.

Instead, RNAi works by inserting genetic material from the same plant species—apples, in the case of the Arctic. This material essentially “tricks” the plant into an immune response that occurs naturally when fighting off invaders or other stresses, according to John Steffens, a former Cornell scientist who pioneered research in this area. The inserted material generates RNA that is coded to attach to existing RNA in the plant—in the case of the Arctic, the RNA responsible for activating the browning enzyme.

The extra RNA tells the plant that something is wrong, so it degrades one of those RNA—the enzyme-activating one. So actually, in the Arctic, the browning enzyme is not so much turned off as never turned on.

The first time Carter’s lab tried the method on an apple, however, it didn’t work. He explains that in the potato, one dominant gene controls browning. Knock it out, and you knock out others that also activate PPO. But in the apple there are four crucial genes. He says it took his company three years to figure it out.

In 2001, he started growing the first Arctic apples in a greenhouse. Over the next decade, he branched out into field trials. “We had to do this slowly to preserve cash,” he says. While he won’t say exactly how much money he’s had at his disposal, he says he’s spent something “less than $10 million.”

He says he also needed time to “cultivate allies” and gather the test results needed to file for regulatory approval. As he did so, anti-GMO activism literally exploded.

“Do not, I repeat DO NOT mess around with our apples!!!!!!!!!!!!

I am sick an tired of having to worry about getting fruit that has been altered with chemicals [sic].”

“Please leave real food alone. We don’t need genetically modified foods . . . period!”

“GMO foods and products, and refined and processed foods, are discouraged since they promote heart disease, diabetes, cancer and other chronic disease.”

These are a few of the 72,745 comments—including form letters circulated by Change.org and others—that flooded the USDA after September 2012 when the agency opened its first 60-day comment period on the Arctic apple petition for deregulation. While some comments were positive, most were not. Like those above, many expressed a distaste for all GMOs, which were portrayed as unnatural and dangerous.

Letters by the Northwest Horticultural Council and the U.S. Apple Association took the opposite tack. “We are not against GE research nor are we flatly against all GE agricultural products,” wrote Schlect from the Horticultural Council. “In fact, we strongly support continued genetics and genomic research.” The problem, he explained, was what he referred to as “marketing issues.” He asserted that those issues would affect not just the Arctic but “the entire United States apple industry.” The U.S. Apple Association’s letter argued the same.

“It’s a very emotional issue in a way that the soybean is not,” Schlect elaborates by phone from Yakima. The apple is not just another commodity, he says. It is “a representation of America”—healthy, wholesome, something you feed your kids. As Schlect and other industry figures see it, having a genetically modified apple on the market could change that image among a public skeptical of GMOs, even if the vast majority of apples remain conventional, regularly bred varieties. “I think there would be confusion,” he says.

Carter responds by saying that Arctic apples would be labeled as such: as “Arctic Golden” or “Arctic Granny Smith,” for instance, in the case of the Arctic varieties under regulatory review. (He’s also developing Arctic varieties of the Gala and Fuji.)

But Schlect says consumers, and some retailers, would likely still wonder whether the apples for sale were genetically engineered. And that could make them stop buying all apples.

The kicker for Schlect is that he sees the Arctic as unnecessary, particularly compared to other GMOs that could literally save an industry. He refers to the Florida citrus industry, which has faced devastating losses due to a fast-spreading disease called citrus greening. Research into a disease-resistant orange is now underway. Should the apple industry face a threat like greening, Schlect says, he could see supporting similar research.

“The consensus is there is just not a demand for a non-browning apple,” adds Wendy Brannen, director of consumer health and public relations for the U.S. Apple Association. “There are other methods to prevent browning.” Many people squeeze lemon juice on apples, for instance, she says. In fact, sliced and packaged apples treated with a chemical found in lemons already exist on the market.

“Do you know how much lemons cost?” asks Herb Aldwinckle, a plant pathologist at Cornell University who is involved in the New York field trial of the Arctic. Not only can using lemons on apples be expensive for individual consumers, he says, but the commercial application of that technique could double the production cost of sliced apples.

John Rice—a seventh-generation Pennsylvania fruit farmer who is one of the largest apple producers on the East Coast—says he’s experimented a fair amount with chemically treated sliced apples, and found that some people detect an artificial taste. That’s one reason he feels—contrary to the official position of his industry—that the Arctic fills a need. He also says that he has to downgrade roughly 80,000 bushels a year due to bruising, costing him about half a million dollars. Goldens, he explains, are particularly susceptible to discoloration because their skins are so light, allowing any browning beneath to be seen clearly.

But that’s not the only reason he enthuses that “the door the Arctic apple opens is one with huge promise on the other side.” The Rice Fruit Company grows peaches as well as apples, and a dozen years ago the dreaded “plum pox virus,” which can affect all stone fruit, landed in the U.S. and hit his peach trees. Knowing that the virus could spread across the country to West Coast orchards, the USDA ordered his peach orchards quarantined and the trees destroyed. “We lost 200 acres,” he says, reckoning the loss cost him $2 million.

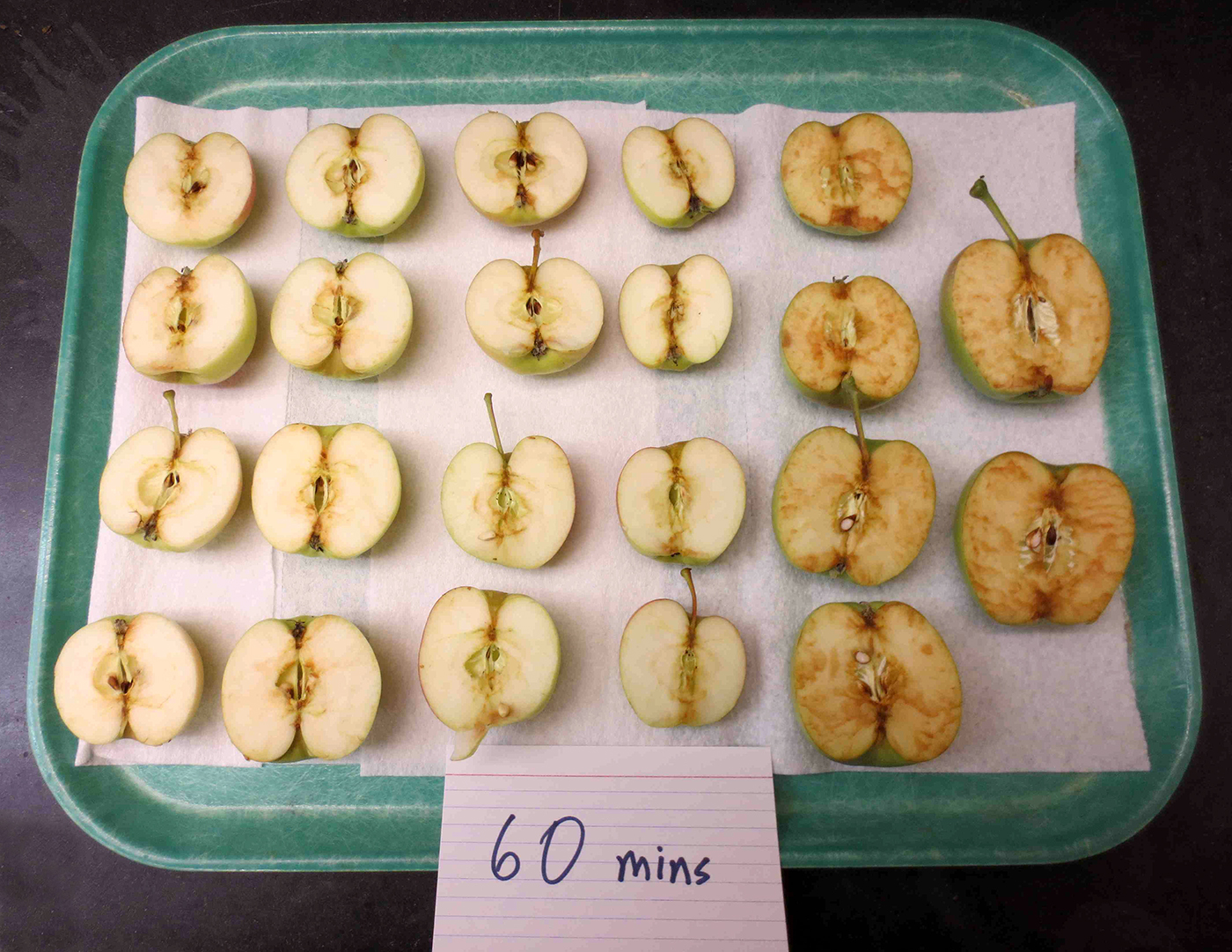

He was interested in what the USDA did next: In collaboration with European colleagues, department scientists developed a virus-resistant genetically engineered plum. So Rice, receptive to the idea of GMOs, sought Carter when he started hearing about the development of Arctic apples. The Canadian farmer subsequently visited Rice at his Pennsylvania operation. As Rice recalls it, Carter cut an Arctic apple at the beginning of their meeting. “We checked it an hour or so later,” Rice says. The slices remained white. “Then we checked it the next day, and the day after that.” White, still.

Rice says he’s very interested in growing Arctics, should they get approval. “On the other hand, if nobody buys the apple because there’s a huge publicity campaign against it, we’d be taking a big risk,” he acknowledges. “It’s hard to know.”

Two days after last month’s election,

which saw the defeat of Washington’s GMO labeling initiative, Friends of the Earth issued a press release. “Companies invested in profits from GMOs might have bought Washington’s election,” the release said, alluding to the record-breaking $22 million in campaign contributions to the No side from Monsanto and other industry groups, “but they can’t stop the market from rejecting their products.”

The organization’s case in point: letters it shared from McDonald’s and Gerber baby-food parent corporation Nestle saying that neither company had any plans to use Arctic apples. Unlike statements from, say, PCC rejecting genetically engineered salmon currently under development, the short letters were boilerplate. They did not rule out the possibility that the companies might use Arctic apples in the future once they were actually on the market. Carter says he’s met with McDonald’s representatives and apple growers that supply Gerber, and both have expressed interest.

Regardless, the environmental group used the occasion to reiterate its opposition to the Arctic and point to its fact sheet on the subject, which maintains that the Arctic is a source of concern for scientists too. For instance, the fact sheet says that scientists believe that “browning may play an important role in helping apples to fend off pests and disease.” A footnote links to a journal article by a plant physiologist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem named Alfred Mayer, whose 2006 paper indeed notes that a “positive correlation” between levels of the browning enzyme and “resistance to pathogens and herbivores” has been “frequently observed.” What the Friends of the Earth fact sheet doesn’t mention is that the paper goes on to say that “convincing proof of a causal relationship, in most cases, still has not been published.” Mayer calls the function of the enzyme “elusive.”

Still, Friends of the Earth and other GMO critics theorize that this correlation may mean that apples in which the enzyme is silenced will require more pesticides. The Organic Consumers Association, in its article bearing the “Frankenapple” headline, goes so far as to assert that the fruit will be “drenched in toxic pesticide residues.”

“That’s complete crap,” says Carter. Both he and Aldwinckle say that more than 10 years of field trials have not turned up any increased susceptibility to pests or disease.

Archer, like other GMO critics, says she is not persuaded by company research, and would like to see independent studies. She also voices a concern that silencing the browning enzyme will mask rotting, thereby posing a danger to consumers who don’t know that the fruit they’re eating has gone bad.

Aldwinckle shares pictures of rotting Arctic apples taken in storage facilities in New York. Big parts of the apples are wrinkled, squishy—and brown. The Cornell scientist explains that browning from rot stems from pathogens rather than PPO, so silencing the enzyme doesn’t stop that process.

The critics’ strongest argument against the Arctic is that RNAi is a relatively new method, not fully understood. They contend that it’s not just the targeted enzyme that could be affected, but unintended targets—maybe ones that aren’t even in the plants themselves, but in the animals and humans eating them.

“There are legitimate scientific questions,” says Michael Hansen, senior staff scientist of the Consumers Union and a prominent anti-GMO spokesperson. Even scientists at the USDA are raising them, he says. He points to a paper published in March that delves into the subject. “The unique characteristics of RNAi and critical knowledge gaps preclude our ability to predict the ecological consequences of this new technology,” says the paper.

Lead author Jonathan Lundgren’s specialty is the study of insects; reached at his South Dakota office, he explains that what particularly troubles him is not a plant like the Arctic, but one in which RNAi is used to target genes in insects, thereby killing them. He acknowledges that “with every meal” we eat plants in which the natural form of RNAi has kicked in. “Obviously we’re not falling over dead,” he says. But RNAi used as an insecticide is specifically designed to overcome the self-defense mechanism of “higher-level organisms”—insects—that consume the altered plant, Lundgren reasons. And if it can do so with insects, maybe it could do so with humans. The Environmental Protection Agency, which weighs in on GMO approval when pesticides are involved, has scheduled a hearing in January to consider this very question.

What implications does this have for the Arctic? Even though his primary concern is insecticidal crops, Lundgren struggles with a response when asked if the apple concerns him. “I don’t know. I don’t know,” he repeats. “That’s a very complicated question. I think we need to be sure . . . We have more questions than answers with this technology.”

In early November, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service released its assessments of the Arctic after three years of deliberations. In 100 pages of documents, the agency expressed much more certainty than Lundgren. Considering the question of unintended targets, the agency concluded that such an effect was unlikely. The apples, it said, “are not engineered for pest resistance, thus there are no ‘target’ species and thus no ‘nontarget’ species either.” The agency also reasoned that the inserted genetic material is so specifically coded that there is little chance of producing any other adverse effect.

The assessments countered other concerns, highlighted the apple’s good points, and indicated that it was on the verge of deregulation.

“Finally, it’s happening,” Carter enthuses a couple of weeks after the assessment came out. “It’s been so long getting to where we are.” While the regulatory process is often dismissed as cursory by critics, he contends “the due diligence is unbelievable,” and overseen by both the Food and Drug Administration as well as the USDA. Although GMOs do not need FDA approval, most are submitted for a voluntary consulting process. At one point, Carter says, the FDA asked him to discuss what would happen to a pig that ate 100 or so apples a day. His researchers delved into the scientific literature to justify their response that the pig would be fine.

When the FDA is through asking questions and considering the answers, it will send Carter a letter indicating its conclusions. As of press time, that has yet to happen. Nor has the Canadian Food Inspection Agency or Health Canada signed off on the Arctic. In fact, last month, the BC Fruit Growers Association wrote to Canada’s health and agriculture ministers asking for a suspension of the regulatory process and a moratorium on the Arctic.

The backlash from the agricultural community has been “a tremendous disappointment,” says Arctic investor Ron Vollo. It has frustrated Carter too, he adds.

The just-finished public-comment period in the U.S. has also sparked a new wave of negativity. “Americans deserve real food,” reads a typical comment among the thousands that poured in.

But Carter, focusing on the positive USDA assessments, insists he is “awesomely excited.” Speaking by phone from Utah, where he’s on a mountain-biking vacation, he says he’s looking forward to an industry convention the following week in Wenatchee. He plans to maintain a booth and meet with growers to argue his case.

“Our story isn’t a 10-minute story,” he says. Part of his pitch will attempt to calm fears that the Arctic will overrun the apple market and provoke a consumer backlash. He tells growers that he intends to go slow—unlike the purveyors of GMO crops like soybeans and sugar beets, which in a few short years spread over millions of acres. His goal: 5,000 to 10,000 acres of Arctic apples in the next 10 years. “We’ll be a very small flea on the side of the elephant,” he says.

He concedes he’ll never neutralize some detractors, including the Horticultural Council’s Schlect. But he’s had one-on-one meetings with members of the Council’s board—individual growers—and senses that they’re more open. “I guess we’re going to let it play out and see what happens,” confirms board member Richard Thomason, who grows apples in Brewster.

“I equate this with the Y2K thing,” Carter muses, referring to the hysteria in some circles that computer problems emerging on January 1, 2000, would bring the world to a standstill: “Everybody was worried about it, and then it happened, and it’s a non-event.” With the Arctic in the final stages of deregulation, this is like the year 1999. When the clock turns and his apples hit the market, that’s all he wants—a non-event.