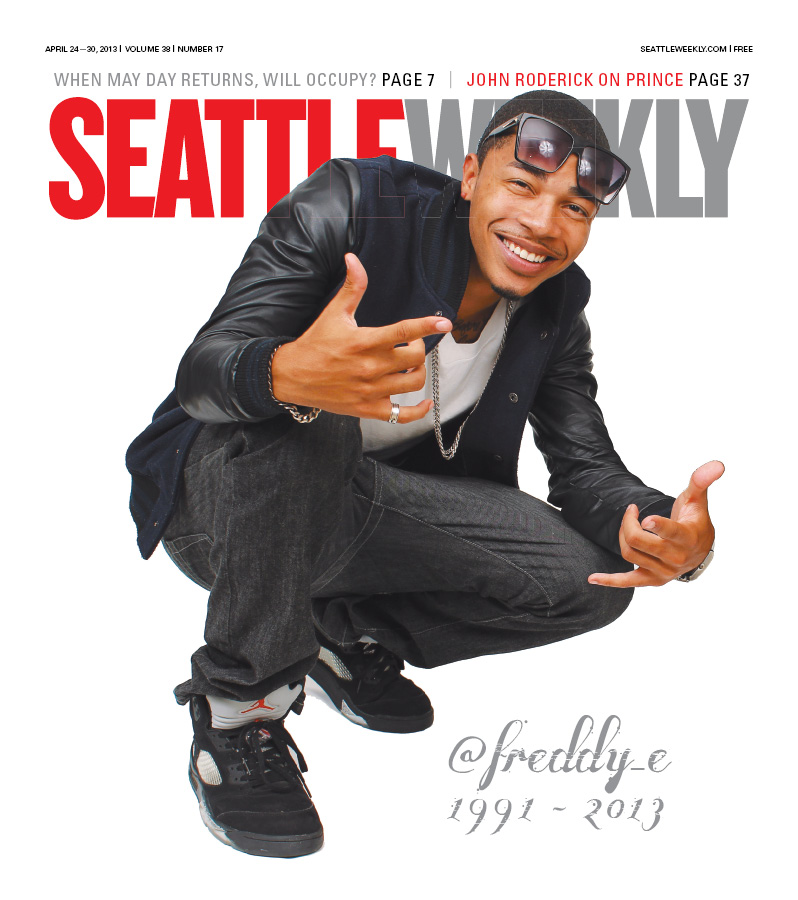

One of the most intriguing and heartbreaking aspects of internet star Freddy Buhl’s suicide (the subject of this week’s cover story) is his family’s contention that the young man was suffering from PTSD.

Freddy never went to war, at least not overseas. The war he witnessed took place over two years in the streets of Seattle, where he witnessed two friends gunned down.

As I note in the story, there’s a growing focus on how urban violence brings on symptoms of PTSD, and efforts to get more services into some especially violent neighborhoods.

This American Life

aired a fantastic segment earlier this year looking at the similarities between the psychological turmoil experienced by a drug dealer in Philadelphia and a veteran who’s just returned to Texas from Afghanistan. Both have flashes of rage, thoughts of suicide, an inability to relax.

In Philly, Drexel University has started a program, Healing Hurt People, to provide PTSD counseling victims of urban violence.

“Often, individuals who have been violently injured have reported that while in the emergency department, their thoughts are to either change their way of life or to retaliate. Most often these youth return, without any supports, to the hostile environment in which they were injured,” notes the group’s website.

The assumption is that upon their return, those men turn violent against other people. And that is often the case. But suicide is also a documented outcome.

Sean Joe, a professor at the University of Michigan, found that suicide rates among young black males rose substantially between 1985 and 2002, in conjunction with a higher prevalence of firearms and drugs in urban neighborhoods combined with lower employment. In other words, as gang warfare erupted, so did suicides.

There’s no evidence Fred Buhl was involved in criminal activity like many of the gang members served by Healing Hurt People, making the fact that he was witness to so much violence all the more troubling: Gun violence is a fact of South Seattle life, for Buhl and many others, regardless of whether they stay away from gangs, to the point that it’s straining the resources this city has in place.

The Youth Violence Prevention Initiative in Seattle originally accepted anyone who fit in one of four criterium: Had been convicted of a crime, had been arrested by SPD, had been suspended from middle school, or had been a victim of violence.

“Most of the youth were coming in that last category, affected by violence,” says program director Mariko Lockhart. “That group is so large, we did not have the capacity to serve them. We got as high as 1,600. It was just too high.”

“There’s just this ripple effect of trauma that I don’t think we are well equipped in this community to deal with.”

At First A.M.E. Church in Capitol Hill, a predominately black congregation, Pastor Carey Anderson has begun a program called Peace in the Streets that he wants to become a collection of services to stop the cycle of violence that has him preceding over too many funerals of men who are too young (including Buhl’s).

“What we’re trying to do with Peace in the Streets is address all of the layers. Get the ball rolling to make the necessary referrals for these young men. Because if it perpetuates, we will lose a whole generation,” he told me. “So often we are working in silos, each trying to do our part, but it takes a village to raise a child; it also takes the building of a village to provide the support these young men need.”

When I asked Anderson about the comparisons that have been made between the psychological trauma experienced by victims of urban violence and soldiers returning from war, he said it was an apt comparison to a point:

“I would think that as opposed to a soldier being sent to an area where there’s a military conflict or campaign going on, with our young people, it’s a constant culture of violence. They never escape it. They’re in it, 24-7. So it’s not like you’re going a tour of duty and get out and have to adjust society again. That is society. Day in and day out. And as a result, many youth don’t believe they’ll make it to 25. So you get at much in as you can, as fast as you can. And so those behaviors need to be redirected.”