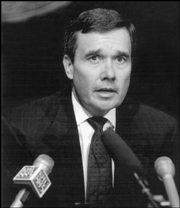

YOU’RE NOT ALONE, Gil Kerlikowske. Even though last week police officers voted overwhelmingly that they have no confidence in Seattle’s chief of police, Kerlikowske can take comfort that right now more than half a dozen police chiefs nationally are under fire from their rank and file. Three more, including chiefs in Prince George’s County, Md., and Providence, R.I., have stepped down in the past year after police unions staged no- confidence votes against them. The trend has even taken hold in Canada, where the Toronto and Calgary police chiefs are fighting combative unions. Police unions know the media love to report a protest. They also recognize that when the cameras roll, mayors sometimes blink and refuse to support their police chief, as just happened in Los Angeles. How did union leaders get so savvy?

Ron DeLord, a former cop who walked the streets of Beaumont, Texas, before the terms “racial sensitivity” and “civilian oversight” were even minted, will take some of the credit. DeLord is a founding member of the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, a well-funded political juggernaut that’s dealt out its share of black eyes in labor disputes with public officials. In 1997, DeLord co-authored Police Association Power, Politics, and Confrontation, a book drawn from his experiences training police unions how to organize. The manual has been a big hit, a sort of bible for police labor leaders, in fact. DeLord has promoted it in Australia and Canada, where it’s talked about so much that Canadian television has interviewed DeLord via satellite from Austin. His publisher has requested a second edition.

DeLord says his book teaches unions how to push their grievances into the public glare, right where police chiefs are most vulnerable. He says a no-confidence vote provides an opportunity for officers to warn the public that unresolved grievances in the department threaten public safety. “The hope is you can articulate enough matters of public concern that then the media and people will ask the mayor, ‘Why aren’t you doing something?'” says DeLord. To find the public’s sympathy, he advises, unions should talk less about their specific grievances and do more to advertise disgruntlement and chaos in the ranks.

In other words, use scare tactics to ward off departmental changes imposed from above. DeLord says unions are right to be skeptical of police chiefs who promise reforms such as tighter restrictions on the use of force and civilian review of officer conduct. Police chiefs are politicians looking for their next job, he contends: They promise the public greater police accountability, open the door for “hot-headed radicals who hate the police” to gain oversight power, then move on.

How widely are DeLord’s tactics utilized? Tulsa police chief Ron Palmer, a longtime colleague of Kerlikowske and the vice president of the Major Cities Police Chiefs Association, pegs the beginning of the recent proliferation of no-confidence resolutions to about the time DeLord’s book first appeared. “Police chiefs who confront strong unions will inevitably come up against no-confidence votes,” agrees Chuck Wexler, director of the Police Executive Research Forum. “It’s one of the strategies unions use to confront [the enforcement of] discipline.” And recent police union uprisings certainly bear the marks of DeLord’s influence.

The Seattle Police Guild is only the latest to employ a strategy that goes beyond addressing internal disagreements to expressing anxiety about the department’s state of affairs. When guild president Ken Saucier decries the unfairness of Kerlikowske’s “double standard” of discipline—publicly criticizing a beat cop who hassled jaywalkers but taking no action against upper-level commanders who let the 1999 Mardi Gras riots get out of hand—he’s sending an obvious warning that the police officer who responds to distress calls is unhappy. If union uprisings in other cities are any indication, look for the guild to make bolder statements about the connection between poor morale and public safety in coming months.

In both Prince George’s County and Los Angeles, police departments notorious for their deadly use of force have dug in against reform-minded chiefs by claiming that officer morale is eroding under poor leadership. The Prince George’s police union even instigated a work slowdown in the midst of a crime wave. Little Rock, Ark., police chief Lawrence Johnson, who is black, has been criticized by his union for promoting black officers in a department traditionally devoid of African-American commanders. But after a no-confidence vote against him, the unions have talked mostly about high-mileage patrol cars and a lack of bulletproof vests.

DeLord says Mayor Greg Nickels’ willingness to talk about problems in the Seattle Police Department is a sign that the guild has gained the upper hand over Chief Kerlikowske, whom DeLord predicts has been “mortally wounded” by the union vote. Not that the guild should kid itself that it can hog-tie Kerlikowske with one vote, DeLord adds. Shaping public opinion takes time, and people initially tend to disapprove when police unions publicly attack the chief of police. “If you polled the public right now, [the guild’s] negatives would be up,” he says. “But people will be listening from here on.”