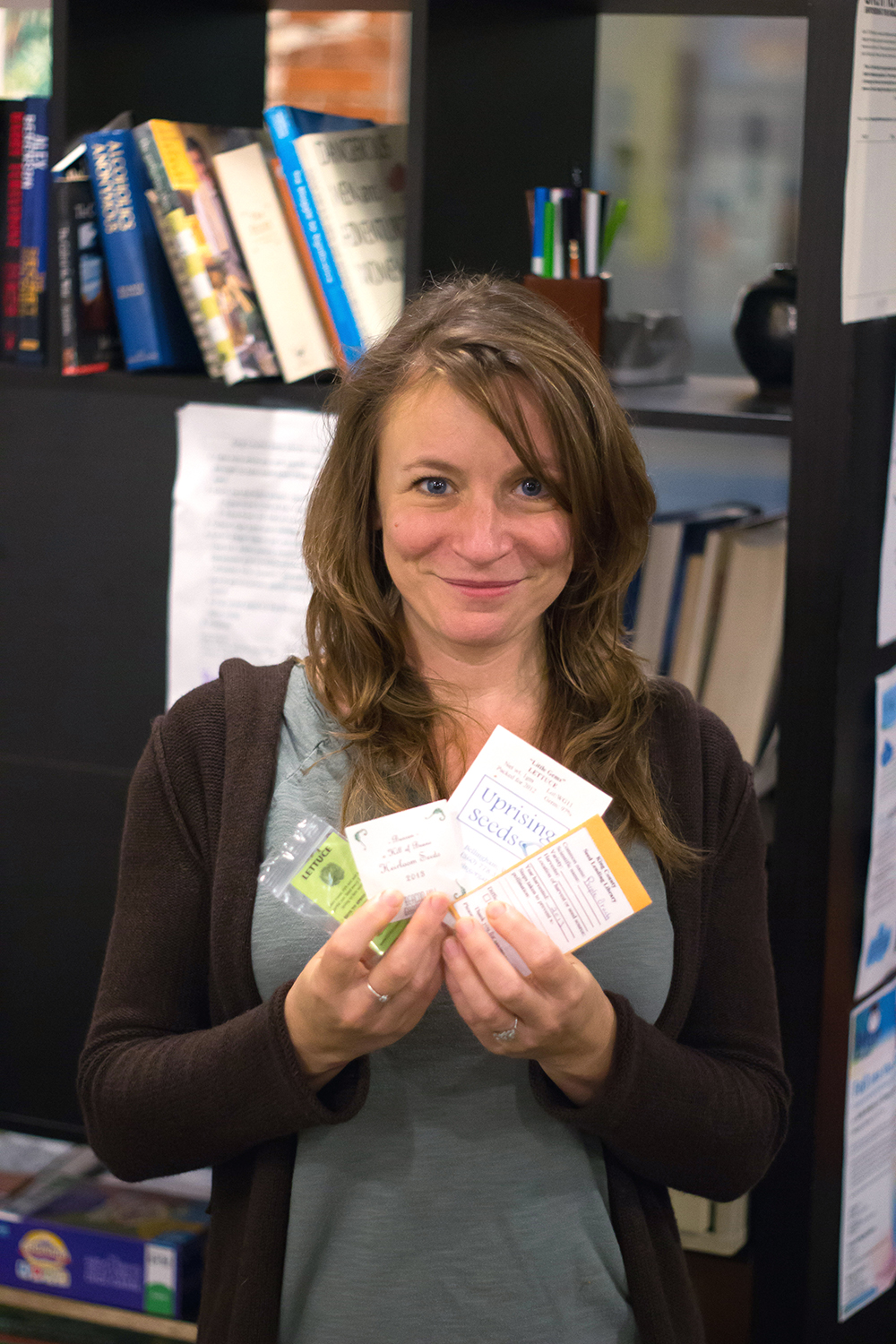

On a bookshelf in a community building in the Hillman City neighborhood, Caitlin Moore, co-director of the King County Seed Library, is showing me a few cluttered boxes of seed packets and explaining how she plans to change the world. “We need to make a change in the food system, which, at its root, depends almost entirely on seeds. If we want a healthy food system, we need a healthy seed system.”

At their most basic, and they don’t get too complicated, seed libraries are a place for the community to share seeds of all types, both edible and aesthetic. The seeds’ origins are varied; some are from commercial companies, but the majority are from small, independent, and usually organic local seed companies or from community gardens.

Hobbyists enjoy collecting seeds from rare, hard-to-find species. Others, like local author and master gardener Bill Thorness, trade seeds with gardening friends. Thorness, who writes books on heirloom plant varieties like his beloved black Spanish radish, told me, “When you give seeds to someone, you’re automatically sharing an interest. You can talk about the methods of growing, what the flowers like, and then also talk about the food.” Sharing mature plants and vegetables, you only get a part of that process.

Sharing seeds in this way, as part of a community, used to be commonplace among farmers. But with the advent of agricultural biotechnology in the ’80s, hybrid and genetically modified seeds produced by larger companies began to offer farmers a deal they couldn’t refuse: pest-resistant seeds and plants that offered higher profit margins. As the big companies grew and began to patent seeds, smaller companies couldn’t compete, and were quickly bought up by increasingly massive seed companies.

Moore explains with a statistic that sounds scary. “There are 10 major companies that control almost 80 percent of the global seed market.” Extrapolating, she explained that this means that 10 companies, essentially, have an effect on nearly all the world’s food, from the vegetables and fruits we eat to the grains and feed we give our cows, pigs, chickens, and goats. At some point, it all starts from a seed. And that seed is usually from the same mega-corporations.

Four major players are in the U.S.: Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, and Syngenta. According to Dr. Philip Howard, an associate professor of food and agriculture at Michigan State University, these four companies alone—in addition to owning a majority of the global market—own more than half the U.S. seed market, and are gobbling more and more of it every day. Between 2008 and 2013, more than 70 seed companies were acquired by one of these big seed firms. The overwhelming majority of these firms push GMO and hybrid seeds to farmers desperate to maintain high-enough yields to make a profit. As more small seed companies get swallowed up, farmers become more dependent on those seeds and more vulnerable to their availability and pricing, leaving small farmers with shrinking profit margins and fewer options.

Industry consolidation is so rampant that in 2010 it triggered a Department of Justice investigation into the possibility that seed-giant Monsanto was involved in anticompetitive business practices. But after two years the DOJ dropped the case, citing “marketplace developments that occurred during the pendency of the investigation” as reasons why it “closed its investigation into possible anticompetitive practices in the seed industry.” In other words, “We’re done looking. Don’t ask why.” Despite requests from various media outlets for more information, the DOJ kept quiet. According to an article in The Wall Street Journal, the only vague indication of why it closed came from a cryptic statement saying “in making its decision, the Antitrust Division took into account marketplace developments that occurred during the pendency of the investigation.”

In 2007, Moore started a website in Olympia attempting to create a community for seed-sharing. At the time, seed libraries were extremely rare, with only a few in the entire country. Moore waited for the seed-savers to come. But nothing happened.

“Despite the discussion of organic and local foods, people weren’t talking about seeds yet. People didn’t know how to save seeds. I realized that was the huge barrier. It wasn’t time yet.” Moore started teaching classes in and around Olympia under the moniker Urban Food Warrior, educating garden clubs and classes about the importance and methods of seed-saving until she had enough interest to start a real seed exchange. Still active, the Olympia Seed Exchange was one of the first in the country when it formed in 2008.

Beyond fighting the consolidation of our global seed market, there are a lot of reasons to encourage the use of seed libraries. First, seeds that come from productive local plants have characteristics that suit them to their particular environment. Seeds from a dinosaur kale that grows well in the dry heat of Dallas probably won’t grow as well in Seattle’s wet weather. Saving seeds enables selection methods that favor natural plant genetics, and encourages a more direct connection with our food and our community.

Moore tells me, “Anytime someone can engage with producing their food or saving their seeds, it keeps them engaged and keeps them thinking about their food system.” Plus, according to her, it helps preserve native species of plants that aren’t common or profitable enough to have a voice in the commercial market, encouraging diversity and allowing us to enjoy a far more interesting selection of plants, both edible and aesthetic.

She adds, “Organic food doesn’t have to be grown from organic seeds to be certified.” This I had a hard time believing, but a quick look at everyone’s favorite page-turner, the Code of Federal Regulations, Title 7, Subtitle B, Chapter I, Subchapter M, Part 205, Subpart C, Article 204 confirms that “Nonorganically produced, untreated seeds and planting stock may be used to produce an organic crop when an equivalent organically produced variety is not commercially available.” In other words, you must use organic seeds unless they’re, like, so totally hard to find.

While some organic seed companies are available to farmers and gardeners, they cannot offer the same diversity of seeds, or the same quality of regionally specific seeds, that seed libraries can. But slowly, independent local seed companies are rising to meet that demand. Places like Adaptive Seeds in Oregon and Uprising Seeds in Bellingham produce organic, typically regionally grown seeds. Moore herself plans to add her own business to the mix by opening a local organic seed company, Root and Radicle, and releasing a book on seed-saving, both early next year.

In some places, though

, the attention seed libraries are getting isn’t the kind Moore is hoping to attract. In June, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture cracked down on a seed exchange run out of a public library in Mechanicsburg. State laws regarding the distribution of seeds, aimed at ensuring that farmers are protected from getting bunk seeds and that invasive species are kept in check, allowed the DOA to shut down the small exchange unless exchangers had their seeds tested for species identification and germination rates—a service that runs about $25 and requires a sample of at least 400 seeds, far more than the backyard gardener is able to produce or share.

We have similar laws here. In a statement released via e-mail, Kathy Davis of the Washington State DOA said, “At this time, the department has no indication that seed libraries present a problem for our state, and we are not currently regulating them.” In other words, the laws are on the books, but possible violations aren’t seen as problematic enough to warrant enforcement.

Currently there are more than 300 seed libraries in the U.S., with two in King County: one housed by Pickering Garden in Issaquah and the main one hosted by Seattle Farm Co-op. Because the Co-op recently lost its lease on its home on Jackson Street in the Central District, a makeshift library now resides at the Hillman City Collaboratory, where I met Moore, until the Farm Co-op confirms its next location. When it does, Moore is hopeful that seed saving will continue to grow. She tells me, “It’s finally becoming part of the conversation—people are starting to talk about what seed libraries are, but more importantly, why it’s important.”