You wouldn’t know it by watching the news or reading the paper, but America’s banks are on the largest crime spree the country has ever known.

In July, Wells Fargo paid a $175 million settlement after the feds caught its brokers systematically pushing minority customers into mortgages with higher rates and fees, even though they posed the same credit risks as whites.

One study found that Wells Fargo charged Hispanics $2,000 more, in what the Justice Department called a “racial surtax.” The bank docked blacks nearly $3,000 extra for their own improper pigmentation.

But despite a colossal civil-rights fraud perpetrated against 30,000 customers, the settlement came to just 1.1 percent of the San Francisco bank’s annual income. It was like forcing a $30,000-a-year working stiff to pay a $330 fine.

Across the country, in Minneapolis, U.S. Bank also swindled its customers, though at least it let whites in on the action. Instead of logging debit-card purchases in the order they were made, the bank rearranged them from highest amount to lowest, the better to artificially stick customers with overdraft fees. U.S. Bank paid $55 million to settle a class-action suit in July. It was the 13th major bank caught running this scam.

Yet these titans of finance were pikers compared to American Express. It promised $300 to anyone who signed up for its Blue Sky card, then decided it would be way better just to stiff them. The company was also caught charging illegal late fees and discriminating against older applicants. The penalty for its sins: $112 million in fines and refunds.

These were just the opening salvos of the assault. Bank of America was caught illegally foreclosing on the homes of active-duty soldiers. Visa and MasterCard were charged with fixing the prices they charged merchants to process credit-card payments. Morgan Stanley colluded to drive up New York electricity prices. And in the most depraved case of all, Morgan Stanley was even sued for allegedly swindling Irish nuns in an investment deal.

If they’d been common robbers, the bankers surely would have faced indictments. After all, their scams have run for years, their breadth and coordination breathtaking. But not a single boss went to jail. Some firms settled for just a fraction of what they’d stolen. Most have never admitted wrongdoing. And in the ethics-optional land known as Wall Street, many saw their stock prices rise.

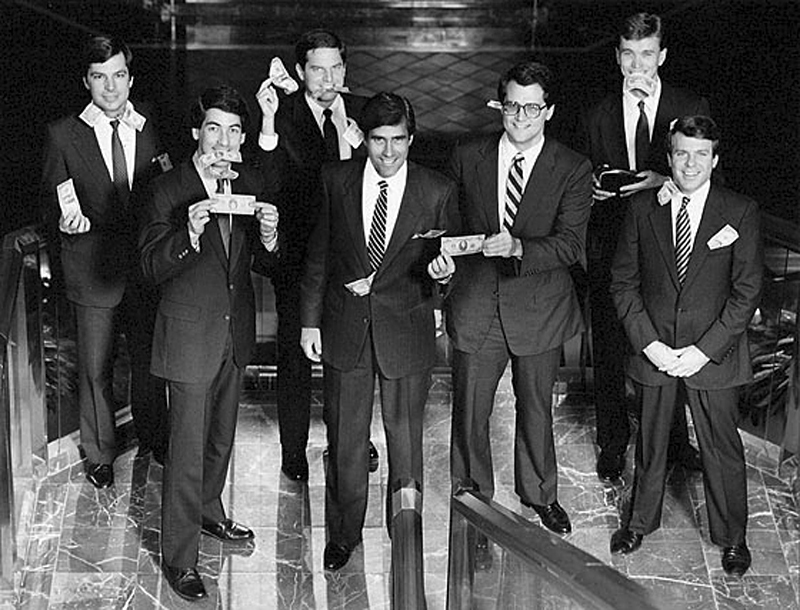

America’s country-club set has forged its own replica of the Mafia—only bigger, broader, and capable of unleashing far more damage on the U.S. economy. “Unquestionably, that’s true,” says Notre Dame law professor G. Robert Blakey, whose career prosecuting organized crime runs all the way back to the Kennedy administration. “I was looking at stuff on Mulberry Street, and the real theft was on Wall Street . . . All of the people who ran the scams have their big houses and their airplanes, and they’re laughing . . . they got away with it.”

The crime wave is a ready-made campaign issue: Gucci villains plundering the middle class. But you haven’t heard a peep out of Barack Obama or Mitt Romney. Both have records they’d prefer you didn’t notice.

The situation leaves Sam Antar with a sense of longing. He’s a former chief financial officer convicted of securities, mail, and wire fraud. “My biggest mistake in life was that I committed my crimes in the 1980s,” he says. “If I committed them today, I wouldn’t even get house arrest. I’d just hire a good lawyer and pay a fine and I’d be free.”

Capitol Hill’s approach to organized crime—at least the yacht-club variety—was on display in June, when JPMorgan Chase chief executive officer Jamie Dimon was summoned to appear before the Senate Banking Committee.

Four years earlier, American taxpayers shoveled him a $25 billion bailout package. But Dimon had since refashioned himself as the sweetheart of Wall Street, the heroic captain who’d weathered the storm. Obama called him “one of the smartest bankers we’ve got.”

On this day, that compliment appeared based on a very low bar. A Morgan trader known as the “London Whale” had just gambled away a stunning $6 billion by making bad bets on the credit markets. His behavior reflected the same strain of incompetence that detonated the economy in 2008.

The senators had presumably summoned Dimon to extract a pound of flesh. Instead the exact opposite happened: They stumbled over themselves with softball questions and blubbering supplication. Typical of the biting line of inquiry was Tennessee Republican Bob Corker: “You’re obviously renowned—rightfully so, I think—for being one of the best CEOs in the country,” he told Dimon. So much for protecting the economy: By the time the hearing was over, Dimon may have needed a post-coital shower.

Conveniently unmentioned at the hearing—or covered in the press—was that JP Morgan was in the midst of a criminal bender that would make the Genovese crime family envious. It began the year before, when Dimon’s bank paid a $27-million settlement for systematically screwing 6,000 active-duty soldiers. JPMorgan was caught overcharging on interest rates and illegally foreclosing on the soldiers’ homes. (The bank did not respond to interview requests.)

Last fall, JPMorgan was nabbed again, this time for violating international sanctions and antiterrorism laws. The Treasury Department cited the bank for engaging in illegal and “egregious” transactions with Iran and Cuba over a five-year period. But instead of being indicted for treason, JPMorgan paid an $88-million settlement to make the problem go away.

In February, the bank was caught gouging customers on overdraft fees. Some were charged hundreds of dollars for being just a few bucks overdrawn. Yet cash—a $110 million settlement, to be exact—again made the accusations disappear.

The crime spree didn’t end until August, when JPMorgan paid another $100 million to settle another class-action suit. This time it was dinged for enticing customers to transfer balances at other banks to its own credit cards. In return, they would only have to pay 2 percent of the debt each month. But the bank quietly raised that minimum to 5 percent—the better to generate late fees.

In a span of 18 months, JPMorgan was involved in three major fraud cases—while moonlighting in money laundering and treason. But not a single executive faced criminal charges. And since the bank posted $25.9 billion in revenue during its most recent quarter, the collective settlements amounted to docking it less than two days’ wages.

The bankers behaved like Mafiosi, and the feds handed out parking tickets.

“It’s just about dollars,” says Mitchell Crusto, a law professor at Loyola University in New Orleans. “If no one’s serving time and no one’s personally liable, I gotta do that all over again.”

Kid-glove treatment for wayward bankers first became fashionable under George W. Bush. In the Orwellian world of conservative economics, he viewed fraud and racketeering statutes as little more than burdensome regulations—at least when it came to the executive crowd. Crimes against consumers were just a lucrative new profit center.

Obama was supposed to change that; he was anti-business, after all, a modern-day Karl Marx with better access to a barber. But this reputation was born of the prattling of Republicans and their televised subsidiary, FOX News. The evidence screams otherwise.

To be fair, the president did push through the Dodd-Frank Act, which includes too-big-to-fail legislation and other measures that hinder banks’ ability to set depth charges across the economy. Obama also created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, whose mission was to return America to the same safeguards that existed under Reagan and the first Bush. But when he appointed Eric Holder attorney general, it was like making John Dillinger’s lawyer head of the FBI bank-robbery unit. Holder, a former Wall Street defense attorney, would ramp up big-dollar settlements. But criminal charges quietly sputtered to a trickle.

Justice Department spokeswoman Dena Iverson disagrees with this interpretation. “We understand there is desire by the public to put company officials behind bars who may be with firms that have committed fraud against the government,” she says in a written statement. “We follow the facts and the evidence, and whenever and wherever we uncover evidence of criminal wrongdoing, we will not hesitate to bring prosecutions.”

Iverson offers a list of people who have been convicted for insider trading, Ponzi schemes, and mortgage fraud. But they’re mostly the smaller fish of finance, people who’ve never slept in the Lincoln bedroom or golfed with John Boehner. Conspicuously absent are racketeering indictments or repeat-offender charges against the likes of Bank of America or JPMorgan.

In a sense, Holder has granted the industry its own version of juvenile court. No matter how pervasive the crime, no matter how many thousands of victims, the major players can be assured of walking away with little more than a fine, released to the custody of their parents.

“When it comes to Wall Street, Eric Holder couldn’t prosecute a ham sandwich that sold itself as kosher,” says Sam Antar. “The Obama administration’s record has been abysmal.” He should know. As the chief financial officer of a retail electronics chain in the 1980s, Antar pleaded guilty to multiple charges of fraud and conspiracy. He now describes himself as a “retired criminal” with a safer career: teaching FBI and IRS agents how to catch people just like him. “It’s kind of like Wall Street has a different set of rules than other industries,” Antar says. “It’s almost like stealing a billion dollars with a pencil is not as bad. You have a lesser chance of going to jail than if you mug somebody on the streets of New York.”

And if Mitt Romney’s elected, he’ll make Bush and Obama look like disciples of Eliot Ness. Romney has vowed to rescind even Obama’s most modest gains, including too-big-to-fail laws. After all, he’s never had an aversion to snuggling up with corruption. Take the case of Drexel Burnham Lambert, the grandest criminal empire in modern Wall Street history. In the 1980s, its CEO, Michael Milken, was being investigated in a massive insider-trading and stock-manipulation case. But Romney, then head of Bain Capital, refused to stop doing business with Drexel, claiming its chieftain had yet to be convicted.

Before Drexel collapsed and Milken was sent to prison, Romney made $175 million with the company.

Former Bain executive Marc Wolpow best expresses the nominee’s business principles: “Mitt, I think, spent his life balanced between fear and greed,” he told The Boston Globe.

So bad has the leniency become that the feds are allowing bankers to keep much of what they steal. Ask Morgan Stanley.

In August, it settled with the Justice Department over its role in fixing New York City’s electricity rates. The bank played middleman in a deal between two energy providers, KeySpan and Astoria Generating, which then colluded to withhold electricity from the market, artificially driving up prices and costing consumers an estimated $300 million.

Morgan Stanley was paid $21 million for arranging the scheme. But the ever-generous Holder let the bank settle for $4.8 million. It marked a stunning new low in federal prosecutions, akin to forcing a bank robber to return just $2,500 after stealing $10,000—with no jail time, of course.

Morgan Stanley offers little defense for its actions. “We will decline comment,” says spokeswoman Mary Claire Delaney. But New York state senator Michael Gianaris will happily fill that silence. “It’s a good business deal for Morgan Stanley,” he says. “They could break the law and get away with almost $17 million in profits for it, so why not do it again? If they get caught—and that’s a big if—they still get 70 percent of the profits.”

Peter Vallone Jr., a Queens councilman and former prosecutor, has never seen such tender handling of criminals. “It didn’t deter a company this big, because it sort of amounts to their lunch budget,” he says. “And most of all, it didn’t return the money to the people it was stolen from. I was a prosecutor for six years, and I’ve never seen someone being fined less than they made.”

Unfortunately, it’s been happening for years. Take the widespread scheme of reordering debit-card purchases to push customers into overdrafts. When it began, Bush’s attorneys general, John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales, refused to prosecute. Private lawyers stepped into the breach with class-action suits.

California attorney Barry Himmelstein was among them. He noticed that bankers had become so entitled, they began to complain that getting caught chopped into their profit margins. “We got that argument from Wells Fargo,” he says. “It’s a ridiculous argument. The fact that you can’t make millions of dollars by screwing your customers is not an excuse to keep screwing them.”

But even in class-action cases, the banks were getting off light. Himmelstein objected to one settlement involving Bank of America, which was also involved in the overdraft scam. By his calculations, the Charlotte, N.C., company had ripped off its customers to the tune of $4.5 billion. Yet the settlement allowed Bank of America to repay just 10 percent of its ill-gotten gains. The average victim was eligible for a $27 refund—less than the cost of a single overdraft.

Four years ago, American taxpayers kept Bank of America afloat with a $45 billion bailout. BofA repaid them by becoming a veritable crime family. Let’s go to the highlight reel:

• Last year, BofA paid a $20 million settlement for illegally foreclosing on soldiers’ homes over a three-year period. (Bank spokesman Larry Grayson declined comment for this story.)

• But it wasn’t until this summer that the bank achieved frequent-guest status in American courtrooms. In June, it was fined for overbilling 95,000 customers over an eight-year period. Total revenue: $32 million. Total fine: $2.8 million.

• A month later, it paid $20 million more to settle a class-action suit. This time it was caught deceiving customers—or simply enrolling them without their knowledge—in worthless credit-card protection programs.

• In August, BofA paid another $738 million in a price-fixing case with Visa and MasterCard. It was accused of conspiring to keep merchant credit-card fees artificially high.

• The bank returned to court in September, this time paying $2.4 billion for deceiving investors over its purchase of Merrill Lynch.

• And just last week, U.S. prosecutors in New York filed a civil complaint against Bank of America seeking $1 billion in damages related to the bank’s “hustle” home-loan program, in which defective mortgages were allegedly approved without proper due diligence, and then sold without warning to either Fannie or Freddie Mac.

In less than two years, Bank of America had chalked up seven major fraud cases. But there was no talk of three strikes. No indictments for racketeering. Not one executive charged with a crime.

The time to break balls was four years ago, believes Ed Mierzwinski of the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, a nationwide federation of consumer advocates. The banking industry was on the verge of collapse. American taxpayers showed up with a $125 billion life preserver. Yet government officials were so worried about imminent carnage, they forgot to ask a simple favor in return: You have to stop ripping us off.

“We could have brought them to heel,” says Mierzwinski. “The bailout was done so fast that they didn’t put in clauses for better behavior.”

Bankers, quite naturally, kept doing what they’d always done. This presented one of those only-in-government ironies: While taxpayers had plenty of money to bail them out, we found our pockets empty when it came time to throw them in prison.

Mierzwinski empathizes with the Justice Department. Banks can field armies of lawyers, who are more than happy to stall and obfuscate as long as the meter’s ticking. The feds cannot, so they retreat to triage, agreeing to settlements that present a mirage of victory.

Former New York governor Eliot Spitzer understands their predicament—somewhat. As his state’s attorney general, Spitzer was the last major politician to launch a sustained assault on financial crime. He too believes that Wall Street has become analogous to the Mafia. “Look, you organize things in a cartel structure very similar to what the mob did,” says Spitzer. “I think it’s also the continuity of the fraud and the pervasiveness.”

Yet Spitzer, now host of Current TV’s Viewpoint With Eliot Spitzer, knows firsthand how difficult it is to drill a multibillion-dollar crime family. Just like Mafia dons, CEOs are insulated from direct involvement—or may not even be aware of the schemes. Moreover, it’s often harder to bring cases that simply pick off henchmen. “Juries don’t like holding mid-level people accountable when the top people are getting off,” says Spitzer.

Professor Blakey doesn’t buy the excuses. Blakey may be America’s most storied organized-crime lawyer. He’s a former federal prosecutor and author of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), the cudgel used to pound the Mafia and corrupt labor unions. It allows prosecutors to charge entire organizations for a continuing pattern of criminality—exactly what the banks are doing.

Back in the 1980s, Rudy Giuliani used the law to take down Romney’s pal Michael Milken. Yet prosecutors have been reticent to use it against corporations ever since. “I am livid that nobody has thought about it,” says Blakey. “I am livid that there are all these civil settlements.”

He notes that the feds have a long history of taking on seemingly invincible foes, from Standard Oil to Big Tobacco: “What’s changed that they could get these convictions and we can’t now?” After all, Blakey argues, corporate criminals are easier to slay. When you subpoena their records, they’ll actually produce them. When Blakey was prosecuting the Teamsters, their books would suddenly go up in flames.

Blakey sees bankers at the bottom of the organized-crime gene pool—their schemes simple and obvious. “They designed a fraud cookie-cutter, and all of these guys have been running comparable scams,” he says. “The variation between scam to scam is minor, and none of them are particularly imaginative.”

But the problem isn’t Attorney General Holder, the professor asserts; it’s the battery of lawyers beneath him. Prosecutors prize their win/loss records like starting pitchers. For them, it’s much better to win a weak settlement than potentially lose a real fight.

In other words, if justice were a bar brawl, the feds would seek out the little guy on crutches.

In May, SunTrust was caught working the same mortgage scam as Wells Fargo. It had charged more than 20,000 black and Hispanic customers higher interest rates and fees than white clients with the same credit profiles. Price to make the problem go away: $21 million.

A month later, ING paid a $619 million settlement for violating international sanctions and antiterrorist laws. It spent a decade providing “state sponsors of terror and other sanctioned entities with access to the U.S. financial system,” Assistant Attorney General Lisa Monaco said at the time.

In July, Capital One was caught luring customers into buying credit-card protection “they didn’t understand, didn’t want, or in some cases couldn’t even use,” said the feds. The company paid $210 million in fines and refunds.

In September, Discover was nabbed running the same scam on 3.5 million customers. The company spent $214 million to make its sins vanish.

For those of you scoring at home: Four major crimes against America. Millions of victims. Zero executives jailed.

“If there are no consequences,” asks Sam Antar, “what incentive do I have to not be a criminal?”