When she was growing up, My-Linh Thai wanted to “stay as far away from government as possible.” She was born in Da Lat, Vietnam, in 1968, during the height of the Vietnam War, and she and her family had to flee the country in 1983.

When they arrived in Washington state, Thai said she saw the government as a “big, organized bully” that was not there “to support, and help, and protect its people.” Still, she said she had a “profound sense of gratitude” for the opportunity to start a second life. Though she had to learn a new language and adjust to a different culture, she graduated with honors from Federal Way High School and from the University of Washington School of Pharmacy. She then became an advocate for ensuring equity and access in education, first as a PTSA parent volunteer, then as a director and president of the Bellevue School Board and vice president of the Washington State School Board Directors Association (WSSDA).

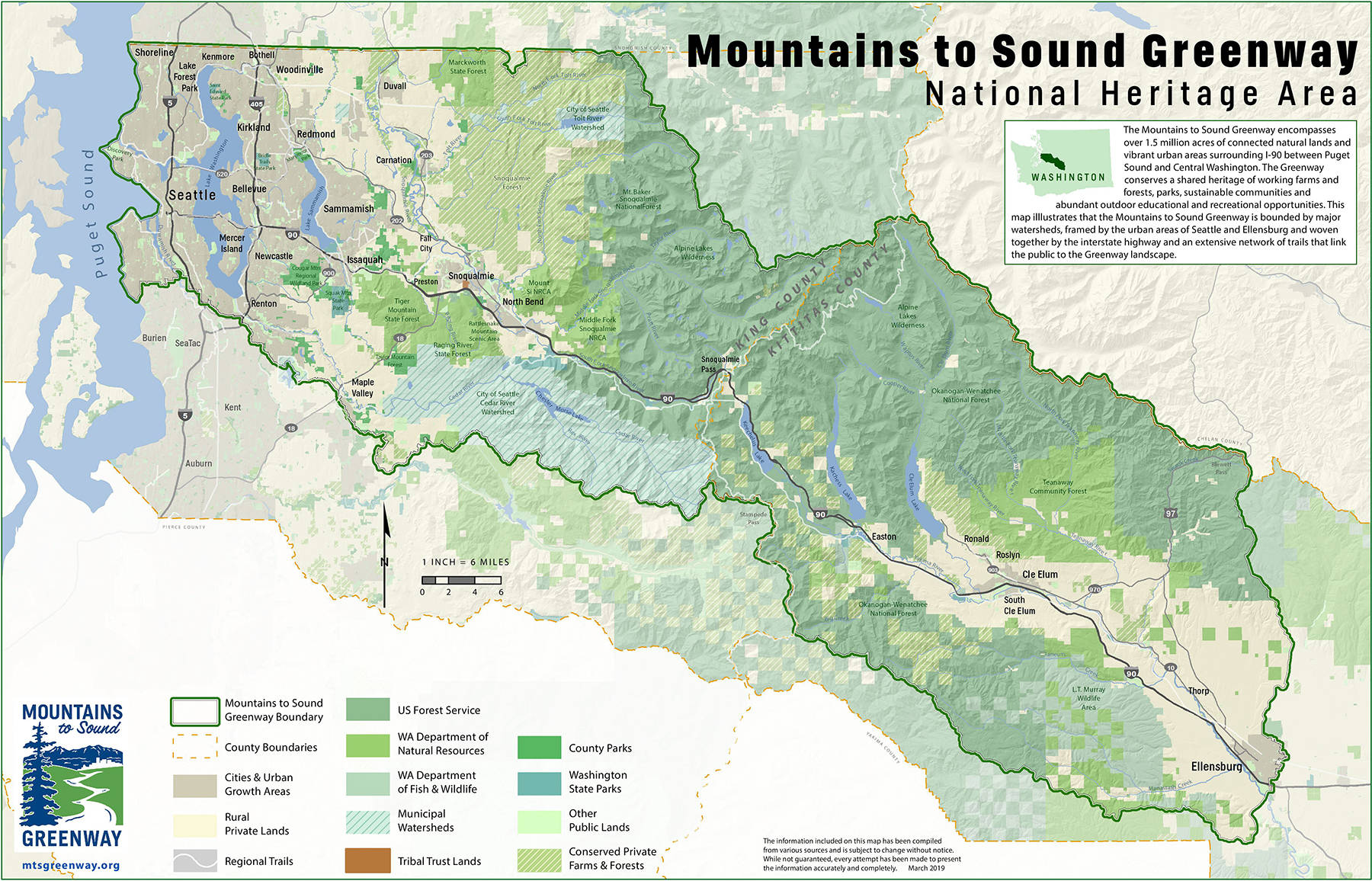

Last year, she ran for state representative in the 41st district, which represents part of King County including Bellevue, Mercer Island, Newcastle, Issaquah, Sammamish, and the northern part of Renton. She won, and became the first refugee to be sworn in to the Washington State Legislature, taking her oath of office during the House’s opening-day ceremonies on Jan. 14. “Our legislature should reflect the many diverse communities throughout our state, and that’s why it is a tremendous honor for me to bring my experience as a refugee to this job,” Thai stated in a press release. “I’m committed to being a voice not only for refugees, but for all communities that are underrepresented in state government.”

This year, Thai (D-Bellevue) brought forward a resolution in recognition of the Lunar New Year—a holiday of great importance to the state’s Asian communities—which was adopted by the Washington State House. (The official Lunar New Year date for 2019 was Feb. 5.) “This state and this country welcomed me warmly, helping me to integrate and realize my potential. With this resolution, I’m expressing my deep gratitude and giving back by sharing something that is special to me personally, and to the Asian community,” Thai said. “This isn’t a small thing. It’s a really big thing. It is saying, ‘We as a state see you and recognize what is important to you.’ ”

Recently, she spoke to Sound Publishing about her childhood and how it inspired her views on refugee-specific and statewide issues. On her resolution, Thai said it’s a small step toward “recognizing, embracing, and including these communities in the bigger, beautiful fabric of Washington.”

Leaving Vietnam

Thai was born a few days short of the Lunar New Year in the central part of Vietnam, as the conflict there was “beginning to change directions,” she said.

Her mother had been the first in her family to attend university, and was the vice president of the national bank. Her father had been an officer for the previous regime in Vietnam, and was jailed for four or five years when Thai was growing up. Thai was one of five children.

Her grandparents lived by the Mekong Delta, and she said she was mostly raised by them. She decided that she wanted to become a doctor after her grandmother fell ill and there was no clinic in their small town. She went to a larger city to receive medical services, and “when she came home, all my aunt and uncle talked about was how amazing the physicians were, and how caring they were.” “At that young age, I dreamed to become a physician so that I could take care of all of the grandparents in the world,” Thai said. “Politics was never part of my equation.”

When Saigon fell in 1975, some of Thai’s extended family members were able to leave the country with “Operation Babylift,” the name given to the mass evacuation of children from Vietnam to the United States. The seven members of Thai’s immediate family tried to leave by boat, and had exhausted their savings after several unsuccessful attempts. In 1975, her mother was diagnosed with uterine cancer, which Thai said sped up the process for reunification with their family who had already reached the U.S. “My aunt put in a paper to petition for us,” Thai said. “On April 28, 1983, we landed at Sea-Tac Airport.”

Thai said she is grateful to have escaped “from a country where we had no political safety.” Others weren’t as lucky, including a group of her uncle’s friends. “[They] never left the Vietnam shore. They were decapitated and their bodies were buried under the water with rocks,” she said. “Those are the horror stories that I get to grow up and live with.”

Arrival

Life didn’t immediately improve when Thai arrived in the Seattle area. She spoke fluent Vietnamese and French, but no English. She was 15 years old, and had been a competitive student in Vietnam. “There was a ranking system, sort of like in Europe,” she said. “If you’re in the top 10 percent, you have an opportunity to attend certain universities… which basically tracks the rest of your career.”

So being unable to “speak and communicate and articulate [her] opinions was very difficult,” she said. She and her siblings often had to act as interpreters for their parents, though they were struggling with the language themselves. “As refugees, we received federal assistance for 18 months… and there are always accountability measures built in every month,” she said. “We as a family had to show that we were going to school, and actively looking for work.” The language barrier and “fear of losing the only lifeline we had” made interacting with the government difficult, she said. She and her family “felt like [they] were being interrogated,” and only judged on their mistakes. “It wasn’t until later that it was recognized that for these families, in order for them to answer questions accurately, they need to understand what questions were being asked,” she said.

Legislative goals

Thai said she is not planning to focus on refugee-specific issues this year (“Maybe in the future,” she said), but that she does want to make the education system more equitable. “With my personal experience as a student in this system and having my own children currently in the system, first and foremost, I believe in public education,” she said. “I believe it is a way to give people opportunity, to advance their knowledge and be a productive member of society… However, our system has so much room to improve.”

As a former healthcare provider, she said her second focus will be on public health. “We could address issues concerning the health and safety of our society and our communities, whether tackling the issues of the opioid crisis, or the sense of safety when it comes to sensible gun laws,” she said.

Equally important, she said, are climate issues. “I hope we could really rally everyone, regardless of our political positions, because once this earth is gone, we all will pay that price,“ Thai said. “I see environmental protection as critical and urgent.”

She also will continue advocating for communities of color. She said she is proud to be the first refugee legislator in Washington, and grateful to the 41st District for electing her. “It speaks to the idea of working toward not only an equitable system in education, but building a thriving community where no one will have to struggle alone,” she said.

There are many issues facing refugees today, she said, especially with some of the policies of the current administration. “If you have the status of being a refugee… it’s a matter of life and death,” she said. “The last thing we want is to be perceived as troublemakers.”

As with the #MeToo movement, Thai hopes to empower refugees to share their stories, and to encourage others to listen. “Trust the victims, trust those who experience [it], because they are the ones who normally would not come up and share, because it takes so much courage to relive those traumas,” she said. “It’s about the voices that were not heard and the stories that were not understood.”

She would like the government and fellow citizens see refugees, as well as students and youth, as people with potential and as future leaders, “who through all of these challenges, will rise up and be so amazing.”

Refugee resources

Eastside Refugee and Immigrant Coalition

Northwest Immigrant Rights Project

Refugee Women’s Alliance

Centro de la Raza