Mayor Ed Murray wants Seattle to become the latest big city to use acoustic technology to pinpoint when gun shots are coming from.

New York City, Milwaukee and other metropolitan areas have deployed the ShotSpotter system in recent years in efforts to tamp down on urban gun violence. A private contractor, ShotSpotter analyzes the data it collects from its headquarters in California and then relays information to police departments.

In a press release, Murray didn’t indicate whether the city would be using ShotSpotter specifically, but the idea is the same: Set up sensors that are activated by the sound of gunshots and relay that information to the police. Also, per the city press release, “A video camera attached to the system is activated to capture the incident.”

Murray’s plan, which must be approved by City Council, would place sensors in the Central District and Rainier Valley neighborhoods to pilot the technology. It’s no coincidence the pilot neighborhoods have prominent African American communities; Murray noted in his prepared remarks that of the 69 people who have been “assaulted by someone with a firearm, more than half of all victims are under the age of 30 and are African American.”

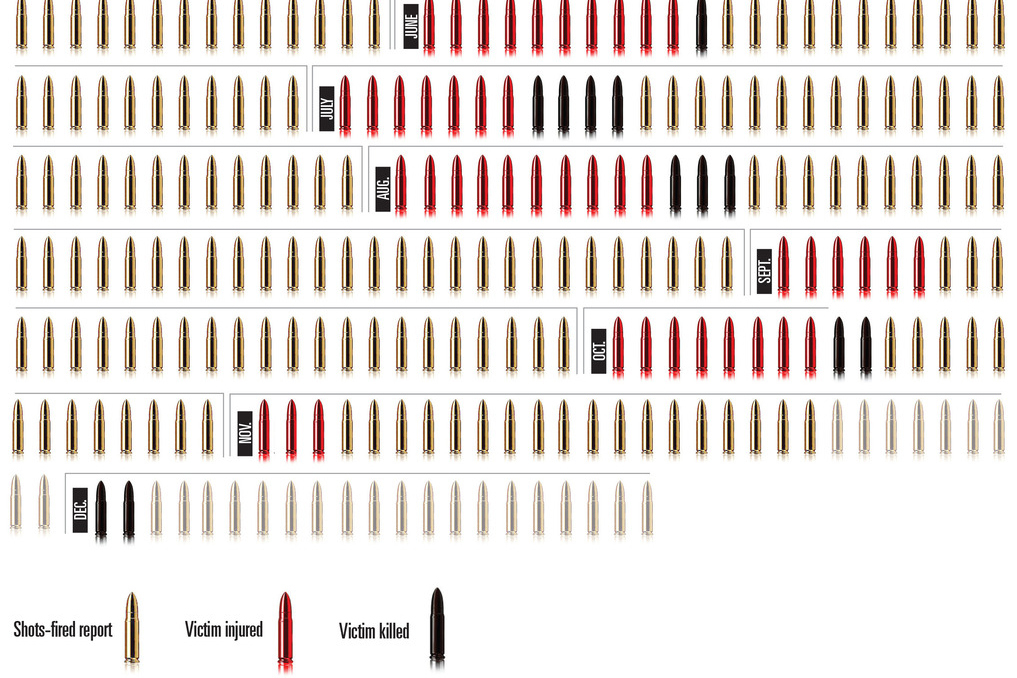

Seattle last year experienced a surge in gun violence, much of it concentrated in Central District and South Seattle neighborhoods. In late July and early August, when gun violence spiked in the city, there were 33 confirmed shots-fired reports. Twenty of those were reported in South Seattle and the Central District and on Capitol Hill, according to a Seattle Weekly analysis of police data.

Murray highlighted support for the program from Seattle’s black community, saying that the concept emerged from meetings with groups including the Urban League and the United Clergy.

But you can all be bet that the program will meet some resistance from Seattle’s active privacy watchdogs. We have a note out to ACLU Washington for comment, but elsewhere in the country privacy concerns have gone hand-in-hand with the technology’s deployment.

Last year, when New York announced it would use ShotSpotter, the New York Times caught up with Eben Moglen, a privacy law professor at Columbia University:

“Moglen … said that programs like ShotSpotter have Fourth Amendment implications. If potentially incriminating evidence is picked up by the microphones, he said, it should not be allowed as evidence, because it constitutes a warrantless search and seizure by collecting public sounds.”

Seemingly in anticipation of privacy concerns, Councilmember Bruce Harrell said in the press release announcing the plan: “I want to make it crystal clear we will work thoroughly with privacy advocates on the operational and data management protocols to ensure the public’s privacy and civil liberties are protected.”

The Seattle Times tells us that the city has considered implementing the technology since 2012. “Then-Mayor Mike McGinn allocated $1 million for a system, but the council later cut the item.”

Update: Sure enough, the ACLU is skeptical. Here’s a statement they just sent out to press, attributed to Shankar Narayan, ACLU of Washington Technology and Liberty Director::

“While we have been asked by the City of Seattle to provide input in the future, the ACLU of Washington has not yet seen details of this particular proposal. At a broader level, however, ShotSpotter technology raises the same kinds of privacy questions that many other government surveillance technologies do—what data will be collected, how long will it be stored, who will have access to it, and will it its use be restricted to the particular purpose it’s being deployed for? In the case of ShotSpotter, we would like to know whether this technology will record only audio, or video as well. If all ambient sounds and/or images, including conversations between innocent bystanders, are being recorded, additional privacy concerns arise. How long is that data kept, and is its use going to be legally restricted to reporting potential gunshots, or might additional law enforcement uses be contemplated in the future? Will this system integrate with others, such as body cameras and license plate readers, to create an ever more inescapable net of government surveillance—a use that the maker of the technology has explicitly contemplated? Finally, while there is the temptation to believe that technology can solve problems of gun violence, the City must still ask whether this is a cost-effective investment based on real data, or whether programs directly addressing the root causes of violence—such as gang prevention and intervention, substance abuse, chemical dependency, or housing programs—will be more effective in solving those problems.

“Washington has the strongest privacy protections in the nation, and our legislature has previously rejected efforts to use networks of government cameras on street corners to spy on and prosecute community members. While the City’s goal of reducing gun violence is laudable, it is important for our City leaders to determine the cost-effectiveness of the investment, and to set clear rules that will restrict the use of this technology to that purpose, before deploying these surveillance devices.”